Abstract

Objective To evaluate the attitudes of parents of 4-8 year-old children with cleft lip and palate (CLP) towards the provision of paediatric dental care and to assess their experience of treatment within the General Dental Services.

Design Postal questionnaire distributed to all parents of 4–8 year-old children on the Birmingham CLP database.

Results The response rate was 77%. Ninety-nine (91%) children were registered with a dentist. Seventy-five (69%) had previously received preventive advice and 32 (29%) had experienced restorative intervention. The majority of parents (64%) expressed a wish for a dental check-up to be provided at the designated Cleft Centre, with 42 (39%) requesting preventive advice. Fifty-eight (67%) of the parents who requested a dental check-up were agreeable for treatment to be provided in the primary sector.

Conclusion The survey indicates there is parental support for paediatric dental assessment at cleft clinics with subsequent arrangement of treatment in the primary sector. The inclusion of paediatric dental support within the multidisciplinary cleft team should be considered as Regional Cleft Centres are established

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Studies have shown that children with cleft lip and/or palate (CLP) have poorer dental health than children in the general population.1,2,3 Achieving optimal dental health may be difficult due to anatomy of the cleft area, malaligned teeth, hypoplastic defects and scarring.1 Evidence also suggests a variation in dental health within the different CLP categories. Children with bilateral cleft lip and palate have a higher caries incidence than those with unilateral clefts.1 Children with cleft lip and palate tend to have poorer oral and gingival health compared with those with isolated clefts of the lip or palate.4

The special needs of children with CLP have been recognised by the Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG), whose remit was to investigate the overall standard of cleft care throughout Great Britain. Their report recommended that preventive advice should be given to the parents of newly born cleft children within one year and paediatric dental services be provided throughout childhood and adolescence.5 However, the report did not state where or by whom these preventative and paediatric services should be provided.

As the incidence of CLP is only 1/700 live births, general dental practitioners may have limited experience in treating these patients6 and as a result may encounter more management problems.7 With the acceptance of the multidisciplinary model as the method of choice for the management of CLP patients,8 it has been proposed that a named member of the cleft team be responsible for ensuring that dental care is being undertaken outside the cleft centre.9 Co-ordination of care from within the multidisciplinary team with provision of preventative programmes and specialist paediatric advice has been shown to reduce caries10 and be cost effective.11 Although not widespread this may be a more effective management approach.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the attitudes of parents of children with CLP towards the provision of paediatric dental care and to assess their experience of dentistry in general dental practice.

Subjects and methods

A postal questionnaire was designed to survey the opinions of parents of children on the Birmingham Children's Hospital CLP database. Face validity and content validity were tested by undertaking one to one interviews with 20 parents and then with a further 20 parents whose first language was not English. The complete questionnaire is given in appendix 1.

Questionnaires were sent to the parents of children in the 4–8 year age range. The lower age limit was chosen because it was felt that many children under the age of 4 years might not be registered with a dentist. The upper age limit was established at 8 years to assess attitudes and experiences prior to the first orthodontic intervention of maxillary expansion, which is undertaken in many children with CLP prior to bone grafting at 8–9 years. If no reply was received within one month, non-respondents were telephoned and another questionnaire provided.

Results

One hundred and fifty eligible patients were recorded on the Birmingham Children's Hospital CLP database. Eight children were excluded; seven with incorrect addresses and one having died. Questionnaires were posted to 142 parents; 109 (77%) were returned. A flow diagram of responses is shown in Figure 1. Sixty-three children (58%) were male compared to 46 females (42%). The median age was 6 years and 1 month with an interquartile range of 5 years and 3 months to 7 years.

Ninety-nine children (91%) were registered with a dental practitioner with only two parents reporting difficulties in registering their child. Both parents stated that the dentist they contacted was not registering any more patients within the NHS and only offered treatment privately. Of the children that were registered 93 (94%) were NHS patients and six (6%) were under private contract. The attendance pattern is given in Figure 2 and shows that 91% of children had received a dental check-up in the preceeding year.

Thirty-two children (29%) had experienced restorative intervention at the dentist with 10 (9%) having had extractions. Seventy-five parents (69%) recalled their child receiving dietary advice while 63 (58%) had been given tooth brushing instruction.

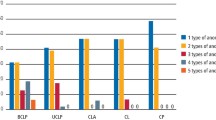

Parental attitudes towards the provision of paediatric dental services are given in Figure 3. Forty-two parents (39%) stated that they would like to receive dietary advice from a paediatric dentist when visiting the Cleft Centre with 20 (18%) not wishing to receive such advice. Seventy parents (64%) stated that they would like a paediatric dentist to provide a dental check-up at the Cleft Centre while 11 (10%) objected.

When the parents who requested a paediatric dental check-up were asked where they would want any necessary treatment performed, thirty-nine parents (46%) chose their own dental practitioner or a dentist closer to their home.

Discussion

The provision of good paediatric dental care for children with CLP is essential for this group of vulnerable patients. Although co-ordination of care has been proposed from within the cleft team,9 this is dependent on patients being able to access dental services in their locality. The present survey found that 91% of children were registered with a dental practitioner, a similar figure to that of 95% documented in the CSAG report (1998).5 Only two parents reported difficulty in accessing NHS dental care for their children contrary to reports that have suggested an unwillingness of dental practitioners to accept certain groups of children as new patients.12

Fifty eight per cent of parents stated that their children had received toothbrushing instruction compared with the 31% previously reported by Hunter et al.13 in children without CLP. A similar discrepancy in relation to dietary advice received by children with CLP (69%) and children without CLP (48%) was found.13 These figures should however be interpreted with caution as the non-cleft group was younger than the cleft group in this survey and was not representative of the general population, being selected on the basis of need for dental extractions under general anaesthesia.13 Overall, parents of children with CLP in our survey appeared to have obtained more advice regarding dental health (69%) than children in the general population (41%) as evaluated in the 1993 Child Dental Health Survey.14 However, a sizeable proportion (31%) of parents of children with CLP had not received any dental health advice.

The final section of the questionnaire evaluated the attitude of parents towards the provision of paediatric services either centrally at the Children's Hospital or locally in the primary sector. Parental opinions concerning this issue have not previously been reported. The results from this questionnaire reveal that the majority of parents (64%) would prefer their child to have a dental examination at the cleft centre. However, if dental treatment was necessary, 46% preferred to have this work undertaken by a local dental practitioner.

The inclusion of paediatric dental support in the cleft team to identify 'at risk' patients and facilitate the provision of care through hospital, community and general dental practitioner based services has been shown to be effective.10 However, the speciality of paediatric dentistry is not routinely represented on the cleft team. This survey indicated that there is parental support for the provision of paediatric dental assessment at centralized cleft clinics with subsequent provision of care within the primary sector. In view of the findings of this study, the inclusion of a paediatric dental specialist in the 'cleft team' should be considered as regional cleft 'centres of excellence' are established in the United Kingdom.

Conclusions

-

Most parents of children with CLP would like a dental examination and preventive advice provided at the cleft centre.

-

There was a preference for any necessary treatment to be undertaken in the primary sector.

References

Johnsen D C, Dixon M Dental caries of primary incisors in children with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate J 1984; 21: 104–109.

Dahlöff G, Ussisoo-Joandi R, Ideberg M, Modeer T. Caries, gingivitis, and dental abnormalities in preschool children with cleft lip and/or palate. Cleft Palate J 1989; 26: 233–237.

Ishida R, Yasafuku Y, Miyamoto A, Ooshima T, Sobue S. Clinical survey of caries incidence in the children with cleft lip and palate. Shohi Shikagaku Zassmi 1989; 27: 716–724.

Paul T, Brandt R S Oral health and dental health status of children with cleft lip and/or palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1998; 35: 329–332.

Clinical Standards Advisory Group 1998. Cleft lip and/or palate. London, The Stationery Office. Series no. HSC 1998/002.

Pannbacker M, Lass N J, Starr P. Information and experience with cleft palate: students, parents, professionals. Cleft Palate J 1979; 16: 198–205.

Dabed C, Cauvi C Survey of dentist's experience with cleft palate children in Chile. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1998; 35: 430–433.

Semb G, Birchgrevink H, Saether I L, Ramstad T. Multidisciplinary management of cleft lip and palate in Oslo, Norway. In: Bardach J, Morris HL, eds. Multidisciplinary management of cleft lip and palate pp 227–239. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 1990.

Shaw W C, Williams A C, Sandy J R, Devlin H B Minimum standards for the management of cleft lip and palate: efforts to close the audit loop. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons 1999; 78: 110–114.

Gregg T A, Johnston D, Pattison K E Efficacy of specialist care for caries in the cleft child. Int J Paed Dent (Suppl.) 1999; 9: 61.

Stephen K W, MacFayden E E Three years of clinical caries prevention for cleft palate children. Br Dent J 1977; 143: 111–116.

Bargman J A, Bulman J S Transfer of child patients from the Community Dental Service to the General Dental Service. Experiences within Wycombe Health Authority. Community Dent Health 1994; 11: 161–163.

Hunter M L, Hood C A, Hunter B, Kingdon A. Oral health advice: reported experience of mothers of children aged five years and under referred for extraction of teeth under general anaesthesia. Int J Paed Dent 1998; 8: 13–17.

O'Brien M. Children's dental health in the United Kingdom 1993. London: HMSO, 1994.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank SheenaWilkes in the Audit Department for assistance in designing the questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDonagh, S., Pinson, R. & Shaw, A. Provision of general dental care for children with cleft lip and palate – parental attitudes and experiences. Br Dent J 189, 432–434 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800792

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800792

This article is cited by

-

Access to primary dental care for cleft lip and palate patients in South Wales

British Dental Journal (2012)

-

An assessment of the contribution of UK specialists in restorative dentistry to cleft lip and palate services

British Dental Journal (2011)