Key Points

-

Presents evidence from a large group of patients (attending general dental practices) demonstrating that worsening oral health correlates with worsening general health

-

Provides further evidence from this group on the association between high-risk lifestyle factors such as smoking and heavy drinking and poor oral health outcomes

Abstract

Aim The primary research question addressed in this paper was 'are lower than average oral health scores observed for those patients who report problems with general health and high-risk lifestyle factors?'

Methods A population analysis was conducted on the first 37,330 patients, assessed by 493 dentists in the UK, to receive a Denplan PreViser Patient Assessment (DEPPA) at their dental practice. The Oral Health Score (OHS) was generated using a mixture of patient-reported factors and clinical findings and is an integrated component of DEPPA. Patients' self-reported risk factors included diabetes status, tobacco use and alcohol consumption. Patients' general health was measured by self-report, that is, a yes/no answer to the question 'have you experienced any major health problems in the last year for example a stroke, heart attack or cancer?' Multivariable linear regression analysis was employed to study the association between the OHS and general health and risk factors for patients in the DEPPA cohort.

Results The mean age of participants was 54 years (range 17-101; S.D. 16 years) and the mean OHS for the group was 78.4 (range 0-100; S.D. 10). 1,255 (3%) of patients reported experiencing a major health problem in the previous year. In the fully adjusted model, diabetes, tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption (three or more drinks per day), and poor overall health in the preceding year were all associated with a statistically significant drop in the mean OHS of patients. Having diabetes was associated with a 1.7 point (95% CI 1.3-2.1, P <0.001) drop in OHS, tobacco use was associated with a 2.7 point (95% CI 2.5-2.9, P <0.001) drop in OHS, and excessive alcohol consumption was associated with a 1.8 point (95% CI 1.3-2.4, P <0.001) drop in OHS. The mean OHS in patients who reported a major health problem in the preceding year was 0.7 points (95% CI 0.2-1.2, P = 0.006) lower than that of patients who did not report a major health problem in the preceding year.

Conclusion The current study has demonstrated that patient reported general health and risk factors were negatively associated with an overall composite oral health score outcome in a large population of over 37,000 patients examined by 493 dentists. While the clinical significance of some of the reported associations is unknown, the data lend support to the growing body of evidence linking the oral and systemic health of individuals. Therefore, GDPs may be in a unique position to influence the lifestyle and general health of patients as part of their specific remit to attain and maintain optimal oral health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is now substantial literature describing the relationship between systemic health and oral, particularly periodontal, health.1

As part of Denplan's PreViser Patient Assessment2 (DEPPA), the oral health status of patients is recorded using the composite 'Oral Health Score'3,4 (OHS). Such measures offer potentially valuable signposts for patient engagement, education and motivation towards behaviour change.5 Standard clinical practice commonly employs separate measurements for each aspect of oral health, however, validated composite measurements are valuable in providing patients with a holistic summary of their oral health outcomes and facilitate oral health improvement targets.

The development, validity, reliability and reproducibility of the OHS has been reported previously by an expert panel of dentists in a pilot study3 and also in another study aimed specifically at the OHS;4 it has also been studied in comparison with the Adult Dental Health Survey.6 Recently elements of DEPPA have been shown to impact favourably on the factors influencing behaviour change in dental patients.7

To date, the association between general health, risk factors and oral health in patients within the DEPPA cohort remains unclear. The existence within the DEPPA database of patient-reported systemic health measures along with current oral health status based upon the OHS, provides the opportunity to explore the association between the two for a large population of patients in a primary dental care setting.

The aim of this paper is to report on the association between current oral health status of patients, as measured using the OHS, and patient-reported risk factors and general health in the preceding year. The primary research question addressed in this paper was 'are lower than average oral health scores observed for those patients who report problems with general health and high risk lifestyle factors?'

As these measures, the OHS and self-reported general health and risk factor status, are computed independently of each other, the null hypothesis is that there is no association between the OHS and such factors within the DEPPA cohort.

Methods

Data from the first 37,330 patients to receive a DEPPA at their dental practice was analysed. A total of 493 different dentists contributed patient assessments to this population.

The OHS is generated based upon:

-

Patient-report of oral pain, function (eating) and appearance

These are recorded online in DEPPA and are then used by the embedded algorithms to produce the composite OHS for each patient based upon their current oral health status. These scores are out of a maximum of 100 which equates to perfect oral health and lower scores indicate worse oral health status.

The remaining general health and lifestyle questions (questions 4 to 17, Fig. 1) inform the Previser future disease risk scores, which are an important part of a full DEPPA report.4 Inputting of this information is either by:

-

The patient completing a paper version of the DEPPA patient questionnaire before their examination and the dental team entering the data online, or

-

The patient completing the questionnaire directly online before their examination, or

-

A dental team member questioning the patient and entering the data online.

In some instances, the dental team need to assist patients with the questionnaire. The clinical inputs required to complete a DEPPA are usually made directly as the patient is examined.

The data submitted by practices during a DEPPA are held centrally in an encrypted and de-personalised form so that only the submitting practice can identify individual patients. However, as reported by Busby et al.,6 reports can be generated in order to produce a national benchmark, audit tables, and for population level analytics.

The DEPPA database was interrogated to report the OHS for each patient as well as lifestyle factors including diabetes, tobacco use, alcohol consumption and any major health problems in the preceding year (question 8, Fig. 1) as a surrogate for the overall general health of patients in the preceding year.

Statistical analysis

Differences in categorical and continuous data were assessed for statistical significance using Pearson Chi-square, t-test and Fisher's exact test as appropriate.

The association between the self-reported general health and OHS of patients within the DEPPA database is reported unadjusted and adjusted for the following covariates: age; self-reported diabetes status (yes or no); tobacco use (ever smoked cigarettes, cigars or pipe or used smokeless tobacco); alcohol status (none, <1 drink/day, 1 drink/day, 2 drinks/day, 3 or more drinks/day); presence of acid reflux (yes or no); and conditions causing vomiting at least once a week (yes or no) (Fig. 1). Also included as covariates were dental assessments of inadequate saliva flow (yes or no) and dental attendance (less than recommended or as recommended). These covariates were included as they could possibly confound the association between general health and OHS by influencing both.

Results

All 37,330 patients in the DEPPA database at the census point for data extraction were included in the analysis. The mean age of participants was 54 years (range 17–101; S.D. 16 years) and the mean OHS for the group was 78.4 (range 0–100; S.D. 10). A total of 1,255 (3%) of patients reported experiencing a major health problem in the last year, 1,875 (5%) reported having diabetes, 22,925 (61%) reported no tobacco use ever, 7,723 (21%) reported no alcohol intake, 345 (1%) reported a health condition that predisposes to vomiting at least once a week and 4,463 (12%) reported acid reflux into the mouth. The dentists assessed inadequate saliva flow in 608 (2%) patients and less than recommended dental attendance in 2,213 (6%) of patients (Table 2).

Patients who self-reported to have experienced a major health problem within the previous year (N = 1,255) were significantly older and had a lower OHS than patients who did not report experiencing a major health problem in the last year. Such patients were also more likely to have diabetes, use tobacco, be teetotal, experience reflux or vomiting, have inadequate saliva flow and be infrequent attenders to their dentist.

Multivariable regression analysis, accounting for age, diabetes status, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, reflux, vomiting, salivary flow and dental attendance attenuated the association between OHS and risk factors and major health problems in the preceding year.

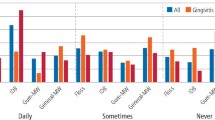

The multivariable analysis demonstrated that, accounting for all other covariates mentioned, having diabetes was associated with a 1.7 point drop in OHS compared to no diabetes, tobacco use was associated with a 2.7 point drop in OHS compared with no tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption (three or more glasses) was associated with a 1.8 point drop in OHS compared with no alcohol consumption and less than recommended dental attendance was associated with a 7.3 point drop in OHS compared with recommended dental attendance. The OHS also decreased in a dose-dependent manner with age with each increase in decade being associated with a 2 point drop in OHS.

In the fully adjusted model, patients who reported major health problems in the last year had a mean OHS that was 3.5 points, 0.7 points (95% CI 0.2-1.2, P = 0.006) lower than those that did not report such problems.

Discussion

This study reports upon the relationship between an established and validated composite oral health assessment system (DEPPA Oral Health Score) and individual lifestyle and general health factors, within general dental practices, from a large population of 37,330 patients. Unlike the Adult Dental Health Survey,8 the study cohort cannot be regarded as a representative sample of the UK population. The dentists conducting these examinations are a self-selecting group of enthusiasts who are the relatively early adopters of DEPPA. Nevertheless, it has previously been demonstrated that headline oral health outcomes in DEPPA are largely consistent with the findings of the ADHS for patients who report regular dental attendance.6

The study demonstrates an association between the OHS and patient reported risk factors and general health in a large cohort of patients. This association was statistically significant after adjusting for major confounders, which was also the case for the association between the OHS and self-reported major health problems in the preceding year, although the effect size was small for the latter. Assuming accurate data entry and self-reporting on behalf of patients, there are a number of potential explanations for the smaller than expected observed association:

-

Self-reported major health problems in the preceding year may be a poor surrogate for overall general health

-

Only 3% of patients reported having such health problems limiting the power of the analysis despite the large sample size

-

The OHS is a composite score of oral health and the association between systemic health and some aspects of such a composite score, for example patient-reported outcomes, is currently poorly understood.

There is currently an international move towards recognising and embracing patient-centred outcomes in research studies, in service planning and evaluation, because optimal clinical health does not necessarily equate to optimal patient-perceived outcomes or improved quality of life. For example, a disease free mouth with a retentive lower partial denture may be regarded as clinically optimal, but the patient concerned may find the lower prosthesis adversely affects their speech, function and self-confidence. DEPPA records patient perceptions of their oral health in the form of function, comfort and aesthetics and embeds these as significant factors in deriving the composite oral health score.

The literature is now replete with data on the relationship between general health and periodontal health in particular.1 Significantly, lower overall oral health scores were also observed in this study group for diabetes patients, consistent with the established negative relationship between diabetes and periodontal disease in particular.9

Busby et al.10 reported how the average OHS tends to fall with increasing age, which may relate in part to the lifetime accumulation of local oral exposures, or may indeed be influenced by chronic systemic conditions of ageing or lifestyle factors. The present data suggest a significantly negative relationship between oral health outcomes and smoking. Furthermore, significantly better oral health scores were observed in patients who have never smoked. There is widespread evidence in the literature (Bergstrom et al.11) supporting a negative effect of smoking specifically on periodontal health and Axlesson et al.12 also observed a negative impact of smoking more generally on oral health.

A negative relationship between periodontal health and drinking alcohol was also reported by Tezal et al.,13 and drinking three or more alcoholic drinks daily also seems to be related to significantly poorer oral health outcomes than average for this study group. Patients who reported having a major health problem in the preceding year were more likely to report being teetotal (29% vs 20%, Table 2). The correlations between the OHS and alcohol intake are interesting and warranted further investigations. In investigating the categories of alcohol consumption, <1 drink per day, 1 drink per day, 2 drinks per day or 3 or more drinks per day, patients who reported having a major health problem were more likely to report drinking three or more drinks per day (4.5% vs 2.8%, data not included in Table 2) or being teetotal (29% vs 20%, Table 2). In examining the relative differences in OHS, compared to teetotallers, patients who reported drinking <1 unit per day had an associated 0.5 point higher OHS (P <0.001), patients reporting drinking 1–2 units per day had roughly similar OHS (P = 0.658 and P = 0.126 respectively) whereas patients reporting drinking three or more units per day had exhibited a 1.8 point lower in OHS (P <0.001). The association between no alcohol intake and poorer oral health scores is consistent with the medical literature, which demonstrates that light to moderate intake of alcohol such as wine reduces all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer and coronary heart disease, whereas high alcohol intake increases mortality risk.14

The poorer OHS evident in those with lower than expected dental attendance is unsurprising and consistent with data from the ADHS.15

As the DEPPA cohort grows (now over 65,000), future analyses of oral health and risk trends and their prospective association with oral and general health outcomes will be interesting to analyse.

While the data presented provide initial insights into the relationship between a composite oral health score and general health and behaviours, longitudinal data analysis is necessary to enable the directionality of the association to be more appropriately analysed. Other limitations of the study include:

-

Missing key covariates (gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, etc) adjusting for which may attenuate the statistical significance of these findings

-

Data entry was performed by a self-selecting group of professionals, who are likely not representative of the wider general dental service. The reliability of the data entered and the comprehensive nature of patient selection are unknown and comparison with ADHS data in the future may be helpful.

-

General health status is only gauged by one question relating to 'major health problems in last year' and while a pragmatic question is necessary for logistical reasons, it limits the granularity of the analysis.

-

The findings cannot be generalised to a community dwelling population who are not DEPPA patients, although the disease patterns in this cohort are similar to the ADHS group as previously reported.6

Conclusions

The current study has demonstrated that patient reported general health and risk factors were negatively associated with an overall composite oral health score outcome, in a large population of over 37,000 patients examined by 493 dentists. While the clinical significance of some of the reported associations is unknown, the data lend support to the growing body of evidence linking the oral and systemic health of individuals. Therefore, GDPs may be in a unique position to influence the lifestyle and general health of patients as part of their specific remit to attain and maintain optimal oral health.

Sources of Funding: Praveen Sharma is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Research Fellowship. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases: Proceedings of a workshop jointly held by the European Federation of Periodontology and American Academy of Periodontology. J Clinical Periodontol 2013; 40 (s14): 1–208.

Delargy S, Busby M, McHugh S, Matthews R, Burke F J T . The reproducibility of the Denplan Oral Health Score (OHS) in general dental practitioners. Comm Dent Hlth 2007; 24: 105–110.

Busby M, Matthews R, Chapple E, Chapple I (2013). Novel online integrated oral health and risk assessment tool: development and practitioners' evaluation. Br Dent J 2013; 215: 115–120.

Burke F J T, Busby M, McHugh S, Delagy S, Mullins A, Matthews R . Evaluation of an oral health scoring system by dentists in general practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 214–218.

Tonetti M S, Eickholz P, Loos B G et al. Primary and secondary prevention of periodontal and peri-implant diseases: Introduction to, and objectives of the 11th European Workshop on Periodontology consensus conference. J Clin Perio 2015; 42: 1–4.

Busby M, Chapple E, Matthews R, Burke F J T, Chapple I . Continuous development of an oral health score for oral health surveys and clinical audit. Br Dent J 2014; 216: 526–527.

Asimakopoulou K, Newton J T, Daly B, Kutzer Y, Ide M . The effects of providing periodontal disease risk information on psychological outcomes – a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Perio 2015; 42: 350–355.

Adult Dental Health Survey (2009). The Health and Social Care Information Centre.

Chapple I L C, Genco R . Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Perio 2013; 40 (s14): 106–112.

Busby M, Martin J, Matthews R, Burke F J.T, Chapple . The relationship between oral health risk and disease status and age, and the significance for general dental practice funding by capitation. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 576–577.

Bergstrom J, Eliasson S, Dock J . Exposure to tobacco smoking and periodontal health. J Clin Perio 2000; 27: 61–68.

Axelsson P, Paulartder J, Lindhe J . Relationship between smoking and dental status in 35-, 50-, 65-, and 75-year-old individuals. J Clin Perio 1998; 25: 297–305.

Tezal M, Grossi S, Ho A, Genco R . Alcohol consumption and periodontal disease. J Clin Perio 2004; 31: 484–488.

Gronbaek M, Becker U, Johansen D . Type of alcohol consumed and mortality from all causes, coronary heart disease, and cancer. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133: 411–419.

Donaldson A N, Everitt B, Newton T, Steele J, Sherriff M, Bower E . The effects of social class and dental attendance on oral health. J Dent Res 2008; 87: 60–64.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the patients and dentists contributing to the DEPPA database

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, P., Busby, M., Chapple, L. et al. The relationship between general health and lifestyle factors and oral health outcomes. Br Dent J 221, 65–69 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.525

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.525

This article is cited by

-

Diabetes knowledge predicts HbA1c levels of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in rural China: a ten-month follow-up study

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

A wider role for general dental practice?

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Periodontal care in general practice: 20 important FAQs - Part two

BDJ Team (2020)

-

Meeting the needs of patients with disabilities: how can we better prepare the new dental graduate?

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Periodontal care in general practice: 20 important FAQs - Part two

British Dental Journal (2019)