Abstract

Study design:

Observational study and cross-sectional survey.

Objectives:

To develop a scale assessing concern about falling in people with spinal cord injuries who are dependent on manual wheelchairs, and to evaluate psychometric properties of this new scale.

Setting:

Community and hospitals, Australia.

Methods:

The Spinal Cord Injury-Falls Concern Scale (SCI-FCS) was developed in consultation with SCI professionals. The SCI-FCS addressed concern about falling during 16 activities of daily living associated with falling and specific to people with SCI. One hundred and twenty-five people with either acute or chronic SCI who used manual wheelchairs were assessed on the SCI-FCS and asked questions related to their SCI and overall physical abilities. A subgroup of 20 people was reassessed on the SCI-FCS within 7 days.

Results:

The SCI-FCS had excellent internal and test–retest reliability (Cronbach's α=0.92, intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC)=0.93). Factor analysis revealed three underlying dimensions of the SCI-FCS addressing concern about falling during activities that limit hand support and require movement of the body's centre of mass. The discriminative ability of the SCI-FCS between different diagnostic groups indicated good construct validity. Subjects with a high level of SCI, few previous falls, dependence in vertical transfers and poor perceived sitting ability demonstrated high levels of concern about falling.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that the SCI-FCS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing concern about falling in people with SCI dependent on manual wheelchairs. The SCI-FCS could also assist in determining the effectiveness of fall minimization programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Falls are common in people with a spinal cord injury (SCI) who are wheelchair dependent. About 40–60% of people using manual wheelchairs report falls.1, 2, 3, 4 Falls represent 60–80% of the non-fatal accidents in wheelchair users,5, 6 and often result from the wheelchair tipping or the person slipping while transferring.1, 3 Typical injuries resulting from falls include contusions (40%), fractures (10%), strains (10%) and lacerations (10%).1, 5, 7, 8 It is our clinical observation and hypothesis that many people with SCI have concerns about falling, some of which are warranted and some of which are not. Unwarranted concerns interfere with a person's ability to participate and achieve independence in activities of daily living. Warranted concerns are also a problem because they indicate safety issues that need to be addressed. To date, research investigating concerns about falling in people with SCI are lacking, primarily because no tool is available to quantify these perceptions.

Most of the work on concern about falling has been performed in the area of gerontology.9 Several questionnaires have been developed over the years,10, 11, 12 but recently the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I) has become the gold standard for assessing concern about falling in older people.11 The FES-I is principally designed for ambulating elderly people, thus in its current format it is not appropriate for assessing concern about falling in people with SCI. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a questionnaire assessing concern about falling in people with SCI. Specifically, the objectives were twofold: (1) to appropriately modify the existing FES-I for people with SCI dependent on manual wheelchairs; and (2) to evaluate psychometric properties of the new scale including internal reliability, test–retest reliability and construct validity. Quantifying concern about falling in people with SCI is important for developing effective intervention strategies.

Methods

Development of the scale

The Spinal Cord Injury-Falls Concern Scale (SCI-FCS) was designed to assess concern about falling during common activities of daily living in people with SCI. Fourteen health professionals (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, rehabilitation nurses and physicians) experienced and working in specialized SCI hospitals within Australia were consulted to select appropriate activities. They were asked to ‘name the 10 most important activities essential to independent living (indoors or outside) that, while requiring some positional change or mobilization, would be safe and non-hazardous to most people with C7 to T12 SCI.’ A second group of eight therapists and nurses were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the choice of activities. The final set of activities was chosen by taking the highest ranked activities based on an agreement of >75% between the two groups of professionals. Five additional activities were chosen based on expert opinion to ensure a range of both easy and challenging tasks were included where people with SCI would have the potential to fall. This resulted in 16 items scored on a 4-point scale (1=not at all concerned to 4=very concerned; see Appendix) similar to the FES-I.11 The total score was calculated by summing the scores for each activity, with a possible range between 16 and 64.11

Participants

A total of 125 people were recruited from the community and local hospitals specializing in SCI. Participants were included if they were over 18 years of age, had a SCI and used a manual wheelchair for at least 75% of their mobility needs. The demographics of all the participants are reported in Table 1. The collection of the data formed part of a larger trial.13 We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Scale administration

All measures were administered during structured telephone or face-to-face interviews by the same physiotherapist. To assist validation of the scale, subjects were assessed, in addition to the SCI-FCS, on their self-perceived fear of falling and their ability to sit supported and unsupported. These were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale. Possible response choices for fear of falling ranged from ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’ and response choices for perceived sitting ability ranged from ‘poor’ to ‘excellent’. Participants were also asked about the number of times they had fallen since their SCI, if they suffered any injury as a result of the fall that affected their mobility and if they were able to perform an independent vertical (floor-to-wheelchair) transfer.

The test–retest reliability of the SCI-FCS was evaluated on a subgroup of 20 participants with a mean (s.d.) of 3.5 (1.4) days between tests. On both occasions, the SCI-FCS was administered by the same assessor using the same protocol (face-to-face or telephone interview). The demographics for this subgroup are reported in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The questionnaire structure was evaluated using Rasch modeling (item response theory; Winsteps, John M Linacre). Rasch modeling concentrates on the probability that an individual with a certain level of concern will answer each item in a given way to match that level of concern.14 Fit statistics were used to examine how well the data from participants and items met the model assumptions.15 The item-respondent map was inspected to evaluate content representation of each item to ensure items and respondents were appropriately targeted.15 Further analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 17, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Factor analysis was performed to assess the unidimensionality of the SCI-FCS and to identify underlying dimensions of concern about falling in people with SCI. Principal component analysis with Varimax rotation was used to determine the number of factors with an eigenvalue >1. An extraction using oblique rotation was then performed to assess the correlation between the factors and a single-factor solution was specified to determine the unity of the scale. Internal reliability of the SCI-FCS was evaluated by calculating the Cronbach α for the whole scale, by checking whether consecutive activities consistently increased the Cronbach α and by examining changes in the Cronbach α when individual activities were added or removed from the scale. In addition, Spearman Rho correlations were calculated between activities. Test–retest reliability was assessed using Kendall's Tauc for individual activities and intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC2,1) for the total SCI-FCS score.

Independent sample t-tests were used to examine construct validity of SCI-FCS, with P-values of <0.05 considered significant. In these analyses, group differences in total SCI-FCS scores were examined according to selected participant characteristics dichotomized by: the presence or absence of self-reported fear of falling; above or below the median perceived sitting ability; falling more or less than once a year (falls per year was calculated by the number of reported falls since injury divided by the time since injury); independence in vertical transfers; above or below mean age; presence or absence of voluntary motor power below T6 (reflecting abdominal muscle innervation); and more or less than 1-year post injury.16

Results

Development of the scale

The list of activities nominated by the first group of experienced SCI professionals is presented in Table 2. The second group of professionals agreed with 60% of the nominated activities. Those activities with >75% agreement were included in the SCI-FCS. Five additional activities were selected from the list by SCI experts to add more physically challenging activities, thus creating a 16-item scale (see Appendix). The scores for the individual SCI-FCS activities ranged from 1 to 4. The total score for the SCI-FCS ranged from 16 to 59. The median (interquartile) total SCI-FCS was 24 (20–33) and the Skewness was 1.144 (s.e.=0.217). No substantial floor or ceiling effects were noted with only 7 and 1% of scores at the minimum and maximum ends of the range.

Questionnaire structure

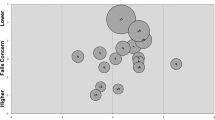

A bubble chart was inspected to ascertain the overall fit of the scale. The item fit indices revealed that all items were good measures of concern about falling (weighted mean square values between 0.77 and 1.31). The weighted t statistic was slightly outside the acceptable range for item 10 (t Outfit Zstd=2.35) (Figure 1). The item-respondent map showed that all items were located between −1.1 and +0.84 logits. Items assessing higher levels of concern (positive logits) were items 2, 4–8, 10, 11 and 15. Items assessing lower levels of concern (negative logits) were items 1, 3, 9, 12–14 and 16. The principal component analysis revealed the greatest eigenvalue was 2.8, supporting the unidimensionality of the scale, with 50% of the variance in the data explained by the model (50% empirical). Factor analysis revealed three dimensions (defined in bold in Table 3). The first factor explained 46% of the variance and was characterized by activities that required minimal movements of the body's centre of mass, such as cooking or dressing. The second factor explained a further 10% of the variance and was characterized by activities that involved a large shift of the body's centre of mass, such as moving around the bed or transferring from one surface to another. The third factor explained a further 9% of the variance and was characterized by activities that required pushing a wheelchair under different conditions, which required additional shifts of the body's centre of mass outside the base of support, such as pushing the wheelchair up a curb. All factors had a fair level of correlation of −0.411 between factors one and two, −0.331 between factors two and three and 0.430 between factors one and three. When a single-factor solution was specified, all activities loaded strongly on a distinct element, explaining 46% of the variance.

Bubble chart for the SCI-FCS as a graphical representation of measure and fit value. Bubbles are named after the item as presented in the Appendix and sized by their standard errors. Items assessing ‘lower levels of concern about falling’ are at the top of physical activity continuum (positive logits) and items assessing ‘higher levels of concern about falling’ are at the bottom (negative logits).

Reliability

Internal reliability of the SCI-FCS was excellent (Cronbach α=0.92). The addition of activities sequentially increased the Cronbach α from 0.63 to 0.92, whereas the removal of one activity at a time (with replacement) did not result in a Cronbach α <0.91. The mean of the inter-activity correlations was 0.42 (range 0.10–0.77). Test–retest reliability for the total score was outstanding with ICC2,1 of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.84–0.97). On the basis of the criteria defined by Landis and Koch,17 most items had moderate to outstanding test–retest reliability (Tauc⩾0.40) (Table 4). Low reliability may have been due to the small test–retest subgroup sample.

Construct validity

Participants who fell once or less per year had significantly higher total SCI-FCS scores than those who fell more than once a year (see Table 5). Participants with the following characteristics also reported significantly higher levels of concern on the SCI-FCS: high level injuries, dependent in vertical transfers, self-reported fear of falling and poor or fair sitting ability (Table 5).

Discussion

The SCI-FCS is the first scale assessing concern about falling in people with SCI dependent on manual wheelchairs. This study shows that the SCI-FCS has a good overall structure covering a wide range of activities that people with SCI need to perform. Both internal and test–retest reliability were excellent. The validity analyses indicate a strong relationship between self-perceived fear of falling and SCI-FCS score. On the basis of this initial validation study, the SCI-FCS could be used as a screening tool for concern about falling in people with SCI for both research and clinical purposes. SCI-FCS may assist in the rehabilitation of people with SCI by guiding professionals in the implementation of tailored intervention strategies aimed at addressing excessive levels of concern about falling and enhancing mobility and community participation.

Responses to individual activities covered the full range of categories available (1–4) and total SCI-FCS scores had a wide spread from 16 to 59 (highest possible score being 64). The activities on the SCI-FCS address a wide range of situations common to people with SCI and necessary for independence,18 with seven items addressing lower levels of concern and nine items addressing higher levels of concern (Figure 1). Moving around the bed was associated with the least concern, whereas pushing a wheelchair on uneven surfaces was associated with the most concern. These activities correspond with some of the most basic and complex skills a person can learn. This item distribution indicates that the scale has a good content representation of the construct, and will allow scoring of people with different levels of concern, as there is a potential for falling in each activity.

Factor analysis identified three underlying dimensions in concern about falling for people with SCI. The factors were segregated by the size of the base of support during the activity as well as the amount of movement of the arms and centre of mass. The first dimension addressed concern during activities requiring minimal movement of the body's centre of mass. Interestingly, some activities grouped in this first factor require large movements, for example picking up objects from the floor. However, we acknowledge that these activities could be modified to necessitate less movement by using assistive devices, such as an ‘easy reach’ stick. Activities included in the second and third dimension involved large shifts of the body's centre of mass, with the third dimension also involving frequent movement of the arms and hands, reducing a person's ability to use the hands to stabilize the body.

Significantly higher levels of concern were reported by participants with partial or full paralysis of the abdominal muscles, self-reported fear of falling, poor or fair supported and unsupported sitting ability, and by participants dependent in vertical transfers. These significant associations indicate that SCI-FCS has good construct validity. Although not significant, there was a trend towards those participants with an acute injury having a greater concern about falling than participants with a chronic injury (P=0.062). This is to be expected because people with recent injury are less skilled at moving and generally more concerned about falling.

Interestingly, and in contrast to older people,19, 20 those who suffered more falls reported significantly less concern. This suggests that many participants may have learnt through experience how to reduce the impact of falls from their wheelchairs. Indeed in this study, no participant reported suffering an injury from a fall that affected their mobility. Unwarranted fear of falling is detrimental to independence because it limits a person's willingness to move and participate. It is therefore important to identify those people concerned about falling and to ascertain whether the concern is justified or not. The SCI-FCS can be used in rehabilitation to identify levels of concern about falling in relation to specific activities, such as negotiating a wheelchair down a slope. In this way, the SCI-FCS can assist in guiding tailored interventions for addressing warranted and unwarranted concerns, thus maximizing mobility and independence to enable greater community participation.

This study is not without its limitations. We used face-to-face, telephone interviews and a convenience sample. We also relied on participants to recall the number of falls they had experienced and the questionnaire item order was not varied. In addition, we retested a small sample of people with chronic injuries within a few days to assess reliability. These participants may not fully reflect the target population and may have remembered their responses. Further validation of the SCI-FCS is needed to address these limitations. In addition, it will be necessary to examine the predictive validity of the SCI-FCS and its sensitivity to change following interventions. It may also be interesting to examine the relation of the SCI-FCS with measurements of depression, anxiety, positive affect, physical ability and participation. Possibly, all are adversely affected by concern with falling or even a cause of unwarranted concern. The falls concern scale described in this study paves the way to explore these and other related issues of importance to people with SCI.

References

Kirby R, Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Brown M, Kirkland S, MacLeod D . Wheelchair-related accidents caused by tips and falls among noninstitutionalized users of manually propelled wheelchairs in Nova Scotia. Am J Med Rehabil 1994; 73: 319–330.

Gavin-Dreschnack D, Nelson A, Harrow J, Ahmed S . Wheelchair related falls: current evidence and directions for improved quality care. J Nurs Qual Care 2005; 20: 119–127.

Gaal R, Rebholtz N, Hotchkiss R, Pfaelzer P . Wheelchair rider injuries: causes and consequences for wheelchair design and selection. J Rehabil Res Dev 1997; 31: 58–71.

Berg K, Hines M, Allen S . Wheelchair users at home: few home modifications and many injurious falls. Am J Public Health 2002; 92: 48.

Xiang H, Chany A, Smith G . Wheelchair related injuries treated in US emergency departments. Inj Prev 2006; 12: 8–11.

Ummat S, Kirby R . Nonfatal wheelchair-related accidents reported to the national electronic injury surveillance system. Am J Med Rehabil 1994; 73: 163–167.

Nelson A, Ahmed S, Harrow J, Fitzgerald S, Sanchez-Anguiano A, Gavin-Dreschnack D . Fall-related fractures in persons with spinal cord impairment: a descriptive analysis. SCI Nurs 2003; 20: 30–37.

Kirby R, Ackroyd-Stolarz S . Wheelchair safety - adverse reports to the United States Food and Drug Administration. Am J Med Rehabil 1995; 74: 308–312.

Legters K . Fear of falling. Phys Ther 2002; 82: 264–272.

Jørstad EC, Hauer K, Becker C, Lamb SE . Measuring the psychological outcomes of falling: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 501–510.

Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, Todd C . Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005; 34: 614–619.

Tinetti M, Richman D, Powell L . Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol 1990; 45: 239–243.

Boswell-Ruys C, Harvey L, Barker J, Ben M, Middleton J, Lord S . Training unsupported sitting in people with chronic spinal cord injuries: a randomised controlled trial. Spinal Cord 2009; Available at http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/sc.2009.88.

Breakwell GM, Hammond S, Fife-Schaw C . Research Methods in Psychology, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006.

Bond TG, Fox CM . Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences 2001.

Burns AS, Ditunno JF . Establishing prognosis and maximizing functional outcomes after spinal cord injury: a review of current and future directions in rehabilitation management. Spine 2001; 26 (24S): S137–SS45.

Landis JR, Koch GG . The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–174.

Harvey L . Management of Spinal Cord Injuries: A Guide for Physiotherapists. Butterworth-Heinemann: Sydney, 2008. pp 57–92.

Howland J, Lachman M, Peterson E, Cote J, Kasten L, Jette A . Covariates of fear of falling and associated activity curtailment. Gerontologist 1998; 38: 549–555.

Afken C, Lach H, Birge S, Miller J . The prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons living in the community. Am J Public Health 1994; 84: 565–570.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Spinal Cord Injury-Falls Concern Scale (SCI-FCS)

We would like to ask some questions about how concerned you are about the possibility of falling. For each of the following activities, please circle the opinion closest to your own to show how concerned you are that you might fall if you did this activity. Please reply thinking about how you usually do the activity. If you currently do not do the activity (for example if someone does your shopping for you), please answer to show whether you think you would be concerned about falling IF you did the activity.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boswell-Ruys, C., Harvey, L., Delbaere, K. et al. A Falls Concern Scale for people with spinal cord injury (SCI-FCS). Spinal Cord 48, 704–709 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Falls risk perception measures in hospital: a COSMIN systematic review

Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes (2023)

-

Cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the spinal cord injury - Falls Concern Scale

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Quality of life, concern of falling and satisfaction of the sit-ski aid in sit-skiers with spinal cord injury: observational study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)

-

Thai translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Spinal Cord Injury Falls Concern Scale (SCI-FCS)

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

A systematic review of dimensions evaluating patient experience in chronic illness

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes (2019)