Abstract

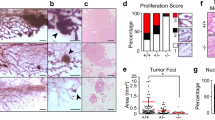

In a previous work, we reported that young transgenic (Tg) mice expressing the intracellular domain of Notch1 (N1IC) showed expansion of lin− CD24+ CD29high mammary cells enriched for stem cells and later developed mammary tumors. Mammary tumor formation was abolished or greatly reduced in cyclin D1−/− or cyclin D1+/− N1IC Tg mice, respectively. Here, we studied the epithelial cell subsets present in N1IC-induced tumors. CD24− CD29int and CD24+ CD29high cells were found to be present at low numbers in tumors. The latter had the same properties as those expanded in young Tg females, and neither cell population showed tumor-initiating potential nor were they required for maintenance of tumors after transplantation. CD24int CD29int cells were identified as tumor-initiating and mammosphere-forming cells and represent a large percentage tumor cells in this model. Their number was significantly lower in tumors from cyclin D1+/− N1IC Tg mice. Using cyclin D1 shRNA knockdown, we also show that N1IC-induced tumor cells remain addicted to cyclin D1 for growth and survival. Interestingly, at lower levels of cyclin D1 or after transplantation in the presence of normal mammary cells, these N1IC-expressing tumor cells reverted to a state of low malignancy and differentiate into duct-like structures. They seem to adopt the fate of bi-potential stem/progenitor cells similar to that of the expanded CD24+ CD29high stem/progenitor cells from which they are likely to be derived. Our data indicate that decreasing cyclin D1 levels would be an efficient treatment for tumors induced by N1 signaling.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 50 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $5.18 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Visvader JE . Keeping abreast of the mammary epithelial hierarchy and breast tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 2009; 23: 2563–2577.

Dontu G, El Ashry D, Wicha MS . Breast cancer, stem/progenitor cells and the estrogen receptor. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2004; 15: 193–197.

Smith GH, Chepko G . Mammary epithelial stem cells. Microsc Res Tech 2001; 52: 190–203.

Kordon EC, Smith GH . An entire functional mammary gland may comprise the progeny from a single cell. Development 1998; 125: 1921–1930.

Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, Stingl J, Smyth GK, Asselin-Labat ML et al. Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature 2006; 439: 84–88.

Stingl J, Eirew P, Ricketson I, Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Choi D et al. Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature 2006; 439: 993–997.

DeOme KB, Faulkin LJ, Bern HA, Blair PB . Development of mammary tumors from hyperplastic alveolar nodules transplanted into gland-free mammary fat pads of female C3H mice. Cancer Res 1959; 19: 515–520.

Smith GH, Medina D . Re-evaluation of mammary stem cell biology based on in vivo transplantation. Breast Cancer Res 2008; 10: 203–208.

Van Keymeulen A, Rocha AS, Ousset M, Beck B, Bouvencourt G, Rock J et al. Distinct stem cells contribute to mammary gland development and maintenance. Nature 2011; 479: 189–193.

Heppner GH . Tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res 1984; 44: 2259–2265.

Shackleton M, Quintana E, Fearon ER, Morrison SJ . Heterogeneity in cancer: cancer stem cells versus clonal evolution. Cell 2009; 138: 822–829.

Illmensee K, Mintz B . Totipotency and normal differentiation of single teratocarcinoma cells cloned by injection into blastocysts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1976; 73: 549–553.

Bussard KM, Boulanger CA, Booth BW, Bruno RD, Smith GH . Reprogramming human cancer cells in the mouse mammary gland. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 6336–6343.

Booth BW, Boulanger CA, Anderson LH, Smith GH . The normal mammary microenvironment suppresses the tumorigenic phenotype of mouse mammary tumor virus-neu-transformed mammary tumor cells. Oncogene 2011; 30: 679–689.

Clarke MF, Fuller M . Stem cells and cancer: two faces of eve. Cell 2006; 124: 1111–1115.

Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M . Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 1253–1261.

Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL . Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001; 414: 105–111.

Gupta PB, Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA . Cancer stem cells: mirage or reality? Nat Med 2009; 15: 1010–1012.

Clevers H . The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med 2011; 17: 313–319.

Ishizawa K, Rasheed ZA, Karisch R, Wang Q, Kowalski J, Susky E et al. Tumor-initiating cells are rare in many human tumors. Cell Stem Cell 2010; 7: 279–282.

Dirks PB . Cancer: stem cells and brain tumours. Nature 2006; 444: 687–688.

Cho RW, Wang X, Diehn M, Shedden K, Chen GY, Sherlock G et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of cancer stem cells in MMTV-Wnt-1 murine breast tumors. Stem Cells 2008; 26: 364–371.

Liu JC, Deng T, Lehal RS, Kim J, Zacksenhaus E . Identification of tumorsphere- and tumor-initiating cells in HER2/Neu-induced mammary tumors. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 8671–8681.

Zhang M, Behbod F, Atkinson RL, Landis MD, Kittrell F, Edwards D et al. Identification of tumor-initiating cells in a p53-null mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 4674–4682.

Vaillant F, Asselin-Labat ML, Shackleton M, Forrest NC, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE . The mammary progenitor marker CD61/beta3 integrin identifies cancer stem cells in mouse models of mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 7711–7717.

Li Z, Tognon CE, Godinho FJ, Yasaitis L, Hock H, Herschkowitz JI et al. ETV6-NTRK3 fusion oncogene initiates breast cancer from committed mammary progenitors via activation of AP1 complex. Cancer Cell 2007; 12: 542–558.

Liu BY, McDermott SP, Khwaja SS, Alexander CM . The transforming activity of Wnt effectors correlates with their ability to induce the accumulation of mammary progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 4158–4163.

Baker M . Melanoma in mice casts doubt on scarcity of cancer stem cells. Nature 2008; 456: 553.

Kelly PN, Dakic A, Adams JM, Nutt SL, Strasser A . Tumor growth need not be driven by rare cancer stem cells. Science 2007; 317: 337.

Zheng X, Shen G, Yang X, Liu W . Most C6 cells are cancer stem cells: evidence from clonal and population analyses. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 3691–3697.

Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, Fullen DR, Johnson TM, Morrison SJ . Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature 2008; 456: 593–598.

Hill RP . Identifying cancer stem cells in solid tumors: case not proven. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 1891–1895.

Rosen JM, Jordan CT . The increasing complexity of the cancer stem cell paradigm. Science 2009; 324: 1670–1673.

Polyak K, Hahn WC . Roots and stems: stem cells in cancer. Nat Med 2006; 12: 296–300.

Li Y, Welm B, Podsypanina K, Huang S, Chamorro M, Zhang X et al. Evidence that transgenes encoding components of the Wnt signaling pathway preferentially induce mammary cancers from progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 15853–15858.

Molyneux G, Geyer FC, Magnay FA, McCarthy A, Kendrick H, Natrajan R et al. BRCA1 basal-like breast cancers originate from luminal epithelial progenitors and not from basal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2010; 7: 403–417.

Lim E, Vaillant F, Wu D, Forrest NC, Pal B, Hart AH et al. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nat Med 2009; 15: 907–913.

Proia TA, Keller PJ, Gupta PB, Klebba I, Jones AD, Sedic M et al. Genetic predisposition directs breast cancer phenotype by dictating progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 8: 149–163.

Callahan R, Egan SE . Notch signaling in mammary development and oncogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2004; 9: 145–163.

Robinson DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Wu YM, Shankar S, Cao X, Ateeq B et al. Functionally recurrent rearrangements of the MAST kinase and Notch gene families in breast cancer. Nat Med 2011; 17: 1646–1651.

Dontu G, Jackson KW, McNicholas E, Kawamura MJ, Abdallah WM, Wicha MS . Role of Notch signaling in cell-fate determination of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Breast Cancer Res 2004; 6: R605–R615.

Bouras T, Pal B, Vaillant F, Harburg G, Asselin-Labat ML, Oakes SR et al. Notch signaling regulates mammary stem cell function and luminal cell-fate commitment. Cell Stem Cell 2008; 3: 429–441.

Ling H, Sylvestre JR, Jolicoeur P . Notch1-induced mammary tumor development is cyclin D1-dependent and correlates with expansion of pre-malignant multipotent duct-limited progenitors. Oncogene 2010; 29: 4543–4554.

Grimshaw MJ, Cooper L, Papazisis K, Coleman JA, Bohnenkamp HR, Chiapero-Stanke L et al. Mammosphere culture of metastatic breast cancer cells enriches for tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res 2008; 10: R52.

Dontu G, Wicha MS . Survival of mammary stem cells in suspension culture: implications for stem cell biology and neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 2005; 10: 75–86.

Sansone P, Storci G, Tavolari S, Guarnieri T, Giovannini C, Taffurelli M et al. IL-6 triggers malignant features in mammospheres from human ductal breast carcinoma and normal mammary gland. J Clin Invest 2007; 117: 3988–4002.

Pece S, Tosoni D, Confalonieri S, Mazzarol G, Vecchi M, Ronzoni S et al. Biological and molecular heterogeneity of breast cancers correlates with their cancer stem cell content. Cell 2010; 140: 62–73.

Hu C, Dievart A, Lupien M, Calvo E, Tremblay G, Jolicoeur P . Overexpression of activated murine Notch1 and Notch3 in transgenic mice blocks mammary gland development and induces mammary tumors. Am J Patho 2006; 168: 973–990.

Hu Y, Smyth GK . ELDA: Extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. J Immunol Methods 2009; 347: 70–78.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant to PJ from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR). PJ is a recipient of a Canada Research Chair. We thank Jean-René Sylvestre for excellent animal care. We are grateful to Annie Lavallée as well as to Éric Massicotte and Julie Lord for their excellent assistance with tissue sections and flow cytometry, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ling, H., Jolicoeur, P. Notch-1 signaling promotes the cyclinD1-dependent generation of mammary tumor-initiating cells that can revert to bi-potential progenitors from which they arise. Oncogene 32, 3410–3419 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.341

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.341

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hormones induce the formation of luminal-derived basal cells in the mammary gland

Cell Research (2019)

-

Loss of Usp9x disrupts cell adhesion, and components of the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways in neural progenitors

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Loss of periostin/OSF-2 in ErbB2/Neu-driven tumors results in androgen receptor-positive molecular apocrine-like tumors with reduced Notch1 activity

Breast Cancer Research (2015)

-

NOTCH1 signaling promotes chemoresistance via regulating ABCC1 expression in prostate cancer stem cells

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2014)