Key Points

-

The success of a number of drugs to treat ocular diseases has resulted in an increased interest in ocular drug discovery.

-

The eye represents a unique and challenging complex organ for applying therapeutics, particularly with respect to drug delivery and access to selective ocular sites.

-

Disease entities covered in the review include diabetes retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, dry eye, cataract, ocular inflammation and ocular infections.

-

Emphasis is placed on pathophysiology and the identity of target sites for retinal diseases and glaucoma, with present and potential drug therapies and screening models highlighted.

-

Target mechanisms discussed included angiogenesis, apoptosis and the extracellular matrix.

-

Sites for potential therapeutic intervention are identified.

Abstract

Millions of people suffer from a wide variety of ocular diseases, many of which lead to irreversible blindness. The leading causes of irreversible blindness in the elderly — age-related macular degeneration and glaucoma — will continue to effect more individuals as the worldwide population continues to age. Although there are therapies for treating glaucoma, as well as ongoing clinical trials of treatments for age-related macular degeneration, there still is a great need for more efficacious treatments that halt or even reverse ocular diseases. The eye has special attributes that allow local drug delivery and non-invasive clinical assessment of disease, but it is also a highly complex and unique organ, which makes understanding disease pathogenesis and ocular drug discovery challenging. As we learn more about the cellular mechanisms involved in age-related macular degeneration and glaucoma, potentially, new drug targets will emerge. This review provides insight into some of the new approaches to therapy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alward, W. L. Biomedicine. A new angle on ocular development. Science 299, 1527–1528 (2003).

Vision problems in the U. S. (2002) Prevent Blindness America; National Eye Institute. www.nei.nih.gov/eyedata/.A great source of data on age-related vision problems in the United States.

Clark, A. F. Current trends in antiglaucoma therapy. Emerging Drugs 4, 333–353 (1999). A general overview of glaucoma pathogenesis and therapeutic targets.

Alward, W. L. M. Glaucoma: The Requisites in Ophthalmology. 1–260 (Mosby, St Louis, 2000). A useful overview of clinical glaucoma.

Fraser, S. & Wormald, R. in Ophthalmology (eds Yanoff, M. & Duker, J. S.) 12:1.1–12:1.6 (Mosby, London, 1999).

Wirtz, M. K. & Samples, J. R. in Glaucoma: Science and Practice (eds Morrison, J. C. & Pollack, I. P.) 12–21 (Thieme Medical, New York, 2003). A great current review on the molecular genetics of glaucoma.

Wudunn, D. Genetic basis of glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 13, 55–60 (2002). A general review of the research that identified various genes associated with glaucoma and glaucoma-related disorders.

Stone, E. M. et al. Identification of a gene that causes primary open angle glaucoma. Science 275, 668–670 (1997).

Vittitow, J. & Borras, T. Expression of optineurin, a glaucoma-linked gene, is influenced by elevated intraocular pressure. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 298, 67–74 (2002).

Rezaie, T. et al. Adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma caused by mutations in optineurin. Science 295, 1077–1079 (2002).

Kass, M. A. et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 120, 701–713; discussion 829–730 (2002). This paper provides sound evidence supporting the role of intraocular pressure-lowering therapy in the prevention of glaucoma.

The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 130, 429–440 (2000). This reference provides sound evidence supporting the role of intraocular pressure-lowering therapy in the treatment of glaucoma

Clark, A. F. & Pang, I. -H. Advances in glaucoma therapeutics. Expert Opin. Emerging Drugs 7, 141–163 (2002). A recent summary of anti-glaucoma therapy.

Medeiros, F. A. & Weinreb, R. N. Medical backgrounders: glaucoma. Drugs Today (Barc.) 38, 563–570 (2002).

Bradley, J. M. et al. Effect of matrix metalloproteinases activity on outflow in perfused human organ culture. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39, 2649–2658 (1998). This paper presents evidence that matrix metalloproteinases regulate outflow resistance and thereby control intraocular pressure.

Wong, T. T. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in disease and repair processes in the anterior segment. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47, 239–256 (2002). An excellent review that focuses on the role of matrix metalloproteinases in the development of various anterior segment disorders.

Parshley, D. E., Bradley, J. M., Samples, J. R., Van Buskirk, E. M. & Acott, T. S. Early changes in matrix metalloproteinases and inhibitors after in vitro laser treatment to the trabecular meshwork. Curr. Eye Res. 14, 537–544 (1995).

Parshley, D. E. et al. Laser trabeculoplasty induces stromelysin expression by trabecular juxtacanalicular cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 37, 795–804 (1996).

Pang, I. -H., Fleenor, D. L., Hellberg, P. E., Stropki, K., McCartney, M. D. & Clark, A. F. Aqueous outflow-enhancing effect of tert-butylhydroquinone: involvement of AP-1 activation and MMP-3 expression. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. (in the press).

Lindsey, J. D. et al. Prostaglandins increase proMMP-1 and proMMP-3 secretion by human ciliary smooth muscle cells. Curr. Eye Res. 15, 869–875 (1996).

Weinreb, R. N., Kashiwagi, K., Kashiwagi, F., Tsukahara, S. & Lindsey, J. D. Prostaglandins increase matrix metalloproteinase release from human ciliary smooth muscle cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 38, 2772–2780 (1997). The important observation that prostaglandins might enhance uveoscleral outflow by stimulating synthesis and release of certain matrix metalloproteinases from ciliary muscle cells.

Quigley, H. A. Experimental glaucoma damage mechanism. Arch. Ophthalmol. 101, 1301–1302 (1983).

Halpern, D. L. & Grosskreutz, C. L. Glaucomatous optic neuropathy: mechanisms of disease. Ophthalmol. Clin. North Am. 15, 61–68 (2002).

Fechtner, R. D. & Weinreb, R. N. Mechanisms of optic nerve damage in primary open angle glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 39, 23–42 (1994).

Wordinger, R. J. & Clark, A. F. Effects of glucocorticoids on the trabecular meshwork: towards a better understanding of glaucoma. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 18, 629–667 (1999). A comprehensive review of the actions of glucocorticoids in the eye and their potential for providing insight into the pathophysiology of glaucoma.

Neufeld, A. H. Nitric oxide: a potential mediator of retinal ganglion cell damage in glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 43 Suppl 1, S129–135 (1999).

Vorwerk, C. K., Gorla, M. S. & Dreyer, E. B. An experimental basis for implicating excitotoxicity in glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Surv. Ophthalmol. 43, S142–150 (1999).

Tezel, G. & Wax, M. B. Increased production of tumor necrosis factor-α by glial cells exposed to simulated ischemia or elevated hydrostatic pressure induces apoptosis in cocultured retinal ganglion cells. J. Neurosci. 20, 8693–8700 (2000).

Yorio, T., Krishnamoorthy, R. & Prasanna, G. Endothelin: is it a contributor to glaucoma pathophysiology? J. Glaucoma 11, 259–270 (2002). A review of the ocular actions of endothelin and its potential as a contributor to the development of glaucoma.

Pang, I. -H. & Yorio, T. Ocular actions of endothelins. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 215, 21–34 (1997).

Wax, M. B., Yang, J. & Tezel, G. Serum autoantibodies in patients with glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 10, S22–24 (2001). A proposed mechanism for glaucoma involving auto-antibodies that are detrimental to optic nerve head function and retinal ganglion cell survival.

Schwartz, M. Physiological approaches to neuroprotection. Boosting of protective autoimmunity. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45, S256–260; discussion S273–276 (2001).

Aihara, M., Lindsey, J. D. & Weinreb, R. N. Reduction of intraocular pressure in mouse eyes treated with latanoprost. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 146–150 (2002).

Avila, M. Y., Carre, D. A., Stone, R. A. & Civan, M. M. Reliable measurement of mouse intraocular pressure by a servo-null micropipette system. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 1841–1846 (2001).

Fanous, M. M., Challa, P. & Maren, T. H. Comparison of intraocular pressure lowering by topical and systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in the rabbit. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 15, 51–57 (1999).

Wang, R. F., Serle, J. B., Gagliuso, D. J. & Podos, S. M. Comparison of the ocular hypotensive effect of brimonidine, dorzolamide, latanoprost, or artificial tears added to timolol in glaucomatous monkey eyes. J. Glaucoma 9, 458–462 (2000).

Morrison, J. C., Nylander, K. B., Lauer, A. K., Cepurna, W. O. & Johnson, E. Glaucoma drops control intraocular pressure and protect optic nerves in a rat model of glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39, 526–531 (1998).

Pederson, J. E. & Gaasterland, D. E. Laser-induced primate glaucoma. I. Progression of cupping. Arch. Ophthalmol. 102, 1689–1692 (1984).

Zhu, M. D. & Cai, F. Y. Development of experimental chronic intraocular hypertension in the rabbit. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 20, 225–234 (1992).

Morrison, J. C. et al. A rat model of chronic pressure-induced optic nerve damage. Exp. Eye Res. 64, 85–96 (1997). A description of an elevated intraocular pressure model in the rat, demonstrating similar optic nerve damage to that in glaucoma.

Anderson, M. G. et al. Mutations in genes encoding melanosomal proteins cause pigmentary glaucoma in DBA/2J mice. Nature Genet. 30, 81–85 (2002). This paper describes a mouse model of glaucoma and identification of the genes involved.

Shareef, S. R., Garcia-Valenzuela, E., Salierno, A., Walsh, J. & Sharma, S. C. Chronic ocular hypertension following episcleral venous occlusion in rats. Exp. Eye Res. 61, 379–382 (1995).

Mittag, T. W. et al. Retinal damage after 3 to 4 months of elevated intraocular pressure in a rat glaucoma model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 3451–3459 (2000).

Ueda, J. et al. Experimental glaucoma model in the rat induced by laser trabecular photocoagulation after an intracameral injection of India ink. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 42, 337–344 (1998).

Wheeler, L. A. & Woldemussie, E. α-2 adrenergic receptor agonists are neuroprotective in experimental models of glaucoma. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 11, S30–35 (2001). This study demonstrated that the α2-agonist brimonidine prevented the loss of retinal ganglion cells in an ocular hypertensive rat model of glaucoma.

Levkovitch-Verbin, H. et al. Translimbal laser photocoagulation to the trabecular meshwork as a model of glaucoma in rats. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 402–410 (2002).

Garcia-Valenzuela, E., Shareef, S., Walsh, J. & Sharma, S. C. Programmed cell death of retinal ganglion cells during experimental glaucoma. Exp. Eye Res. 61, 33–44 (1995).

Johnson, E. C., Deppmeier, L. M., Wentzien, S. K., Hsu, I. & Morrison, J. C. Chronology of optic nerve head and retinal responses to elevated intraocular pressure. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 431–442 (2000).

Cioffi, G. A., Orgul, S., Onda, E., Bacon, D. R. & van Buskirk, E. M. An in vivo model of chronic optic nerve ischemia: the dose-dependent effects of endothelin-1 on the optic nerve microvasculature. Curr. Eye Res. 14, 1147–1153 (1995). One of the first studies demonstrating that endothelin can mimic chronic optic nerve ischaemia and produce optic nerve damage.

Flammer, J., Pache, M. & Resink, T. Vasospasm, its role in the pathogenesis of diseases with particular reference to the eye. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 20, 319–349 (2001).

Stokely, M. E., Brady, S. T. & Yorio, T. Effects of endothelin-1 on components of anterograde axonal transport in optic nerve. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 3223–3230 (2002).

Krishnamoorthy, R. R. et al. Characterization of a transformed rat retinal ganglion cell line. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 86, 1–12 (2001).

Pang, I. -H., McCartney, M. D., Steely, H. T. & Clark, A. F. Human ocular perfusion organ culture: a versatile ex vivo model for glaucoma research. J. Glaucoma 9, 468–479 (2000).

Clark, A. F., Wilson, K., De Kater, A. W., Allingham, R. R. & McCartney, M. D. Dexamethasone-induced ocular hypertension in perfusion-cultured human eyes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 36, 478–489 (1995).

Borras, T., Brandt, C. R., Nickells, R. & Ritch, R. Gene therapy for glaucoma: treating a multifaceted, chronic disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 2513–2518 (2002). A good overview of gene considerations, target tissues and delivery systems for instituting gene therapy for glaucoma.

Clark, A. F., Lane, D., Wilson, K., Miggans, S. T. & McCartney, M. D. Inhibition of dexamethasone-induced cytoskeletal changes in cultured human trabecular meshwork cells by tetrahydrocortisol. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 37, 805–813 (1996).

Fleenor, D. L., Pang, I. -H. & Clark, A. F. Involvement of AP-1 in interleukin-1α-stimulated MMP-3 expression in human trabecular meshwork cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. (in the press).

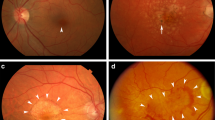

Benson, W. E. in Ophthalmology (eds Yanoff, M. & Duker, J. S.) 8:20.1–28:20.10 (Mosby, London, 1999). An excellent overview of the epidemiology and clinical aspects of diabetic retinopathy.

Aiello, L. P. Vascular endothelial growth factor and the eye: biochemical mechanisms of action and implications for novel therapies. Ophthalmic Res. 29, 354–362 (1997). An excellent review on the role of vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular neovascularization.

Gardner, T. W., Antonetti, D. A., Barber, A. J., Lanoue, K. F. & Levison, S. W. Diabetic retinopathy: more than meets the eye. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47, S253–262 (2002). An excellent overview on the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema.

Barber, A. J. A new view of diabetic retinopathy: a neurodegenerative disease of the eye. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 27, 283–290 (2003).

Engerman, R. L. & Kern, T. S. Retinopathy in galactosemic dogs continues to progress after cessation of galactosemia. Arch. Ophthalmol. 113, 355–358 (1995).

Kowluru, R. A. Retinal metabolic abnormalities in diabetic mouse: comparison with diabetic rat. Curr. Eye Res. 24, 123–128 (2002).

Robison, W. G. Jr, Nagata, M., Laver, N., Hohman, T. C. & Kinoshita, J. H. Diabetic-like retinopathy in rats prevented with an aldose reductase inhibitor. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 30, 2285–2292 (1989).

Fong, D. S. Changing times for the management of diabetic retinopathy. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47, S238–245 (2002).

Lund-Andersen, H. Mechanisms for monitoring changes in retinal status following therapeutic intervention in diabetic retinopathy. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47, S270–277 (2002).

Aiello, L. P. The potential role of PKC β in diabetic retinopathy and macular edema. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47 Suppl 2, S263–269 (2002).

Jaffe, G. J. et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of an intraocular fluocinolone acetonide sustained delivery device. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 3569–3575 (2000).

Ciulla, T. A., Criswell, M. H., Danis, R. P. & Hill, T. E. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide inhibits choroidal neovascularization in a laser-treated rat model. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 399–404 (2001).

Martidis, A. et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 109, 920–927 (2002).

Edwards, M. G., Bressler, N. M. & Raja, S. C. in Ophthalmology (eds Yanoff, M. & Duker, J. S.) 8:28.1–28:28.10 (Mosby, London, 1999). A good general overview of clinical aspects of age-related macular degeneration.

Husain, D., Ambati, B., Adamis, A. P. & Miller, J. W. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol. Clin. North Am. 15, 87–91 (2002).

Crabb, J. W. et al. Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14682–14687 (2002). A sophisticated proteomics approach to age-related macular degeneration pathogenesis.

Hageman, G. S. et al. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch's membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 20, 705–732 (2001). This paper presents a new hypothesis involving inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration.

Anderson, D. H., Mullins, R. F., Hageman, G. S. & Johnson, L. V. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 134, 411–431 (2002).

Agarwal, N. et al. Levobetaxolol-induced up-regulation of retinal bFGF and CNTF mRNAs and preservation of retinal function against a photic-induced retinopathy. Exp. Eye Res. 74, 445–453 (2002).

Seiler, M. J. et al. Selective photoreceptor damage in albino rats using continuous blue light. A protocol useful for retinal degeneration and transplantation research. Graefes. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 238, 599–607 (2000).

A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, β-carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 1417–1436 (2001).

Okamoto, N. et al. Transgenic mice with increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in the retina: a new model of intraretinal and subretinal neovascularization. Am. J. Pathol. 151, 281–291 (1997).

Penn, J. S. & Henry, M. M. Assessing retinal neovascularization in an animal model of proliferative retinopathy. Microvasc. Res. 51, 126–130 (1996).

Robinson, G. S. et al. Oligodeoxynucleotides inhibit retinal neovascularization in a murine model of proliferative retinopathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 4851–4856 (1996).

Griggs, J. et al. Inhibition of proliferative retinopathy by the anti-vascular agent combretastatin-A4. Am. J. Pathol. 160, 1097–1103 (2002).

Garcia, C. et al. Efficacy of Prinomastat (AG3340), a matrix metalloprotease inhibitor, in treatment of retinal neovascularization. Curr. Eye Res. 24, 33–38 (2002).

Bainbridge, J. W. et al. Inhibition of retinal neovascularisation by gene transfer of soluble VEGF receptor sFlt-1. Gene Ther. 9, 320–326 (2002).

Murata, T. et al. Response of experimental retinal neovascularization to thiazolidinediones. Arch. Ophthalmol. 119, 709–717 (2001).

Smith, L. E. et al. Essential role of growth hormone in ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. Science 276, 1706–1709 (1997).

Preclinical and phase 1A clinical evaluation of an anti-VEGF pegylated aptamer (EYE001) for the treatment of exudative age-related macular degeneration. Retina 22, 143–152 (2002).

Presta, L. G. et al. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res. 57, 4593–4599 (1997).

Krzystolik, M. G. et al. Prevention of experimental choroidal neovascularization with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody fragment. Arch. Ophthalmol. 120, 338–346 (2002).

Das, A., McLamore, A., Song, W., McGuire, P. G. Retinal neovascularization is suppressed with a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor. Arch. Ophthalmol. 117, 498–503 (1999).

Friedlander, M. et al. Involvement of integrins αv β3 and αv β5 in ocular neovascular diseases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9764–9769 (1996).

Clark, A. F., Bingaman, D. P. & Kapin, M. A. Ocular angiostatic agents. Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 10, 427–448 (2000).

Clark, A. F. AL-3789: a novel ophthalmic angiostatic steroid. Exp. Opin. Invest. Drugs 6, 1867–1877 (1997).

Penn, J. S., Rajaratnam, V. S., Collier, R. J. & Clark, A. F. The effect of an angiostatic steroid on neovascularization in a rat model of retinopathy of prematurity. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 283–290 (2001).

Rechtman, E., Ciulla, T. A., Criswell, M. H., Pollack, A. & Harris, A. An update on photodynamic therapy in age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 3, 931–938 (2002).

Sieving, P. A. in Ophthalmology (eds Yanoff, M. & Duker, J. S.) 8:11.1–18:11.10. (Mosby, London, 1999).

Zack, D. J. et al. What can we learn about age-related macular degeneration from other retinal diseases? Mol. Vis. 5, 30 (1999). A good overview of the molecular genetics of retinal degenerative diseases.

Stone, E. M., Sheffield, V. C. & Hageman, G. S. Molecular genetics of age-related macular degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 2285–2292 (2001). A good overview of the molecular genetics of retinal degenerative diseases.

Allikmets, R. et al. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nature Genet. 15, 236–246 (1997).

Weber, B. H., Vogt, G., Pruett, R. C., Stohr, H. & Felbor, U. Mutations in the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP3) in patients with Sorsby's fundus dystrophy. Nature Genet. 8, 352–356 (1994).

Petrukhin, K. et al. Identification of the gene responsible for Best macular dystrophy. Nature Genet. 19, 241–247 (1998).

Stone, E. M. et al. A single EFEMP1 mutation associated with both Malattia Leventinese and Doyne honeycomb retinal dystrophy. Nature Genet. 22, 199–202 (1999).

Stone, E. M. et al. Allelic variation in ABCR associated with Stargardt disease but not age-related macular degeneration. Nature Genet. 20, 328–329 (1998).

de la Paz, M. A., Pericak-Vance, M. A., Lennon, F., Haines, J. L. & Seddon, J. M. Exclusion of TIMP3 as a candidate locus in age-related macular degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 38, 1060–1065 (1997).

Allikmets, R. et al. Evaluation of the Best disease gene in patients with age-related macular degeneration and other maculopathies. Hum. Genet. 104, 449–453 (1999).

Felbor, U., Doepner, D., Schneider, U., Zrenner, E. & Weber, B. H. Evaluation of the gene encoding the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 in various maculopathies. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 38, 1054–1059 (1997).

Weber, B. H. et al. A mouse model for Sorsby fundus dystrophy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 2732–2740 (2002).

Rakoczy, P. E. et al. Progressive age-related changes similar to age-related macular degeneration in a transgenic mouse model. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 1515–1524 (2002).

Fauser, S., Luberichs, J. & Schuttauf, F. Genetic animal models for retinal degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47, 357–367 (2002).

Chang, B. et al. Retinal degeneration mutants in the mouse. Vision Res. 42, 517–525 (2002).

Chader, G. J. Animal models in research on retinal degenerations: past progress and future hope. Vision Res. 42, 393–399 (2002). A good introduction to animal models for retinal degeneration.

Yamazaki, H. et al. Preservation of retinal morphology and functions in royal college surgeons rat by nilvadipine, a Ca2+ antagonist. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 919–926 (2002).

McGee Sanftner, L. H., Abel, H., Hauswirth, W. W. & Flannery, J. G. Glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor delays photoreceptor degeneration in a transgenic rat model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Ther. 4, 622–629 (2001).

Liang, F. Q. et al. AAV-mediated delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor prolongs photoreceptor survival in the rhodopsin knockout mouse. Mol. Ther. 3, 241–248 (2001).

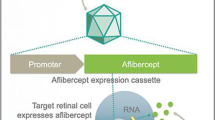

Campochiaro, P. A. Gene therapy for retinal and choroidal diseases. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2, 537–544 (2002). A good overview on the potential use of gene therapy for retinal diseases.

Acland, G. M. et al. Gene therapy restores vision in a canine model of childhood blindness. Nature Genet. 28, 92–95 (2001).

Bielory, L. Update on ocular allergy treatment. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 3, 541–553 (2002).

Bielory, L. Ocular allergy guidelines: a practical treatment algorithm. Drugs 62, 1611–1634 (2002). An overview of new therapeutic drugs for treatment of ocular allergy

Yanni, J. M. et al. A current appreciation of sites for pharmacological intervention in allergic conjunctivitis: effects of new topical ocular drugs. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. Suppl. 228, 33–37 (1999). An overview of new therapeutic drugs for treating allergic conjunctivitis.

Kunert, K. S., Tisdale, A. S. & Gipson, I. K. Goblet cell numbers and epithelial proliferation in the conjunctiva of patients with dry eye syndrome treated with cyclosporine. Arch. Ophthalmol. 120, 330–337 (2002).

Fujihara, T., Murakami, T., Fujita, H., Nakamura, M. & Nakata, K. Improvement of corneal barrier function by the P2Y(2) agonist INS365 in a rat dry eye model. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 96–100 (2001).

Calonge, M. The treatment of dry eye. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45, S227–239 (2001). A summary of new therapeutic approaches for treating dry eye.

Nelson, M. L. & Martidis, A. Managing cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 14, 39–43 (2003).

Foster, C. S. et al. Efficacy and safety of rimexolone 1% ophthalmic suspension vs 1% prednisolone acetate in the treatment of uveitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 122, 171–182 (1996).

Leibowitz, H. M. et al. Intraocular pressure-raising potential of 1. 0% rimexolone in patients responding to corticosteroids. Arch. Ophthalmol. 114, 933–937 (1996).

Bodor, N. Retrometabolic drug design—novel aspects, future directions. Pharmazie 56, S67–74 (2001).

Howes, J. F. Loteprednol etabonate: a review of ophthalmic clinical studies. Pharmazie 55, 178–183 (2000).

Thielen, T. L, Castle, S. S. & Terry, J. E. Anterior ocular infections: an overview of pathophysiology and treatment. Ann. Pharmacother. 34, 235–246 (2000).

Guembel, H. O. & Ohrloff, C. Opportunistic infections of the eye in immunocompromised patients. Ophthalmologica 211, 53–61 (1997).

Smith, A., Pennefather, P. M., Kaye, S. B. & Hart, C. A. Fluoroquinolones: place in ocular therapy. Drugs 61, 747–761 (2001).

Goldstein, M. H., Kowalski, R. P. & Gordon, Y. J. Emerging fluoroquinolone resistance in bacterial keratitis: a 5-year review. Ophthalmology 106, 1313–1318 (1999).

Schoenwald, R. D. in Textbook of Ocular Pharmacology. (eds Zimmerman, T. J., Kooner, K. S., Sharir, M. & Fechtner, R. D.) 119–138 (Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, 1997). A good introduction to ocular pharmacokinetics.

Sasaki, H. et al. Enhancement of ocular drug penetration. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug. Carrier Syst. 16, 85–146 (1999).

Kaur, I. P. & Kanwar, M. Ocular preparations: the formulation approach. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 28, 473–493 (2002).

Loftsson, T. & Stefansson, E. Cyclodextrins in eye drop formulations: enhanced topical delivery of corticosteroids to the eye. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 80, 144–150 (2002).

Kaur, I. P. & Smitha, R. Penetration enhancers and ocular bioadhesives: two new avenues for ophthalmic drug delivery. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 28, 353–369 (2002).

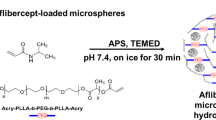

Kimura, H. & Ogura, Y. Biodegradable polymers for ocular drug delivery. Ophthalmologica 215, 143–155 (2001).

Geroski, D. H. & Edelhauser, H. F. Transscleral drug delivery for posterior segment disease. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 52, 37–48 (2001). A discussion of a new delivery route for drugs to treat disorders at the back of the eye.

Ke, T. L., Clark, A. F. & Gracy, R. W. Age-related permeability changes in rabbit corneas. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 15, 513–523 (1999).

Sheffield, V. C. et al. Genetic linkage of familial open angle glaucoma to chromosome 1q21-q31. Nature Genet. 4, 47–50 (1993).

Fauss, D. J. et al. in Basic Aspects of Glaucoma Research III (ed. Lutjen-Drecoll, E.) 319–330 (Schattauer, New York, 1993).

Nguyen, T. D. et al. Gene structure and properties of TIGR, an olfactomedin-related glycoprotein cloned from glucocorticoid-induced trabecular meshwork cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6341–6350 (1998).

Kubota, R. et al. A novel myosin-like protein (myocilin) expressed in the connecting cilium of the photoreceptor: molecular cloning, tissue expression, and chromosomal mapping. Genomics 41, 360–369 (1997).

Fingert, J. H. et al. Analysis of myocilin mutations in 1703 glaucoma patients from five different populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 899–905 (1999).

Fingert, J. H., Stone, E. M., Sheffield, V. C. & Alward, W. L. Myocilin glaucoma. Surv. Ophthalmol. 47, 547–561 (2002). An excellent update on the role of myocilin in glaucoma with emphasis on describing MYOC mutations, expression heredity, and pathogenesis.

Alward, W. L. et al. Clinical features associated with mutations in the chromosome 1 open-angle glaucoma gene (GLC1A). N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 1022–1027 (1998).

Alward, W. L. et al. Variations in the myocilin gene in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 120, 1189–1197 (2002).

Tamm, E. R. Myocilin and glaucoma: facts and ideas. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 21, 395–428 (2002). An excellent review of myocilin, from gene structure to myocilin localization and function.

Lam, D. S. et al. Truncations in the TIGR gene in individuals with and without primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 1386–1391 (2000).

Kim, B. S. et al. Targeted disruption of the myocilin gene (Myoc) suggests that human glaucoma-causing mutations are gain of function. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 7707–7713 (2001).

Clark, A F. et al. Glucocorticoid induction of the glaucoma gene MYOC in human and monkey trabecular meshwork cells and tissues. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 1769–1780 (2001).

Filla, M. S. et al. In vitro localization of TIGR/MYOC in trabecular meshwork extracellular matrix and binding to fibronectin. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 151–161 (2002).

Fingert, J. H. et al. Evaluation of the myocilin (MYOC) glaucoma gene in monkey and human steroid-induced ocular hypertension. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 42, 145–152 (2001).

Fautsch, M. P., Bahler, C. K., Jewison, D. J. & Johnson, D. H. Recombinant TIGR/MYOC increases outflow resistance in the human anterior segment. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 41, 4163–4168 (2000).

Caballero, M., Rowlette, L. L. & Borras, T. Altered secretion of a TIGR/MYOC mutant lacking the olfactomedin domain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1502, 447–460 (2000).

Jacobson, N. et al. Non-secretion of mutant proteins of the glaucoma gene myocilin in cultured trabecular meshwork cells and in aqueous humor. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 117–125 (2001).

Zhou, Z. & Vollrath, D. A cellular assay distinguishes normal and mutant TIGR/myocilin protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2221–2228 (1999).

Klein, B. E., Klein, R. & Lee, K. E. Incidence of age-related cataract over a 10-year interval: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology 109, 2052–2057 (2002).

Panchapakesan, J. et al. Five year incidence of cataract surgery: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 87, 168–172 (2003).

McKinnon, S. J. et al. Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing-4 protects optic nerve axons in a rat glaucoma model. Mol. Ther. 5, 780–787 (2002).

Tatton, W. G. Apoptotic mechanisms in neurodegeneration: possible relevance to glaucoma. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 9, S22–29 (1999). A good review of the apoptotic pathways involved in glaucoma.

Hare, W. et al. Efficacy and safety of memantine, an NMDA-type open-channel blocker, for reduction of retinal injury associated with experimental glaucoma in rat and monkey. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45, S284–289; discussion S295–286 (2001).

Wood, J. P., Desantis, L., Chao, H. M. & Osborne, N. N. Topically applied betaxolol attenuates ischaemia-induced effects to the rat retina and stimulates BDNF mRNA. Exp. Eye Res. 72, 79–86 (2001).

Neufeld, A. H., Sawada, A. & Becker, B. Inhibition of nitric-oxide synthase 2 by aminoguanidine provides neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells in a rat model of chronic glaucoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9944–9948 (1999).

Tatton, W. G., Chalmers-Redman, R. M. & Tatton, N. A. Apoptosis and anti-apoptosis signalling in glaucomatous retinopathy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 11, S12–22 (2001).

Nakazawa, T., Tamai, M. & Mori, N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents axotomized retinal ganglion cell death through MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43, 3319–3326 (2002).

Ko, M. L., Hu, D. N., Ritch, R., Sharma, S. C. & Chen, C. F. Patterns of retinal ganglion cell survival after brain-derived neurotrophic factor administration in hypertensive eyes of rats. Neurosci. Lett. 305, 139–142 (2001).

Zhou, J. et al. Characterization of RGS5 in regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Life Sci. 68, 1457–1469 (2001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Glossary

- CATARACT

-

An opacity of the lens that causes the loss of transparency and/or the scattering of light entering the eye.

- AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION

-

Retinal neurodegenerative disease of the aged that leads to the progressive loss of central vision.

- GLAUCOMA

-

A heterogeneous group of optic neuropathies that lead to progressive vision loss and blindness.

- OPHTHALMOLOGY

-

The branch of medicine that deals with the eye and eye diseases.

- TRABECULAR MESHWORK

-

Reticulated tissue at the junction of the iris and cornea which imparts resistance to aqueous humour outflow and thereby regulates intraocular pressure.

- OPTIC NERVE HEAD

-

Region at the back of the eye where ∼1 million retinal ganglion cell axons exit the eye through the sclera to form the optic nerve.

- OCULAR HYPERTENSION

-

Condition in which the pressure inside the eye (intraocular pressure) is higher than normal (usually defined as >21 mm Hg)

- MATRIX METALLOPROTEINASES

-

Family of extracellular enzymes responsible for the degradation and turnover of extracellular matrix molecules.

- RETINOPATHY

-

Degenerative disease of the retina, which is the multilayered neural tissue of the eye responsible for phototransduction and integration of visual signals.

- VASCULAR ENDOTHELIAL GROWTH FACTOR

-

A cytokine responsible for vascular leakage and neovascularization.

- DRUSEN

-

Deposits containing complex lipids and calcium that can accumulate with age.

- BRUCH'S MEMBRANE

-

Basement membrane that separates the retinal pigment epithelium from the vascular choroid.

- MACULA

-

Central region of the retina with the highest concentration of cone photoreceptors that is responsible for color and acute vision.

- DRY EYE

-

A condition characterized by ocular discomfort and caused be ocular tissue deficiencies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, A., Yorio, T. Ophthalmic drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2, 448–459 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1106

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1106

This article is cited by

-

Hybrid Electrospun Polycaprolactone Mats Consisting of Nanofibers and Microbeads for Extended Release of Dexamethasone

Pharmaceutical Research (2016)

-

The potential of stem cell research for the treatment of neuronal damage in glaucoma

Cell and Tissue Research (2013)

-

Structural evidence of differential forms of nanosponges of beta-cyclodextrin and its effect on solubilization of a model drug

Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry (2013)

-

Delivery Systems and Local Administration Routes for Therapeutic siRNA

Pharmaceutical Research (2013)

-

Challenges in the development of glaucoma neuroprotection therapy

Cell and Tissue Research (2013)