Key Points

-

Several factors make ovarian cancer a difficult disease to treat effectively. Although many patients experience symptoms, these often overlap with other ailments, and many patients are diagnosed after the cancer has metastasized. Ovarian cancer is also heterogeneous — multiple genetic and epigenetic changes are evident in patients with ovarian cancer; however, how such changes are selected for during tumorigenesis is not yet clear.

-

Mutation and loss of TP53 function is one of the most frequent genetic abnormalities in ovarian cancer and is observed in 60–80% of both sporadic and familial cases. Of the 16 candidate tumour suppressor genes identified to date in ovarian cancer, 3 are imprinted genes. Several growth inhibitory genes are also silenced by methylation or imprinting.

-

Inheritance of DNA repair defects contributes to as many as 10–15% of ovarian cancers. The lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer in mutation carriers varies with the genetic defect (for BRCA1 30–60%, for BRCA2 15–30% and for hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer 7%).

-

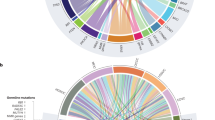

At least 15 oncogenes have been implicated in ovarian cancers, and DNA copy number abnormalities have also been found in loci that are known to contain non-coding microRNAs. At least seven signalling pathways are activated in >50% of ovarian cancers, and mutations that affect cell proliferation, apoptosis and autophagy are also evident.

-

Ovarian cancer can be split into two groups on the basis of genetic changes: low-grade tumours with mutations in KRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on chromosome Xq, microsatellite instability and expression of amphiregulin; and high-grade tumours with aberrations in TP53 and potential aberrations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, as well as LOH on chromosomes 7q and 9p.

-

Changes in cell adhesion and motility also contribute to disease development and metastasis. Adhesion of ovarian cancer cells to the mesothelial cells and to the underlying stroma is mediated by CD44, CA125 and b1 intergrin on the surface of ovarian cancer cells that bind to mesothelin and hyaluronic acid on mesothelial cells, or to fibronectin, laminin and type IV collagen in the underlying matrix.

-

A crucial goal is to identify patients who would benefit from particular targeted therapies. Given the complexity of crosstalk between protein signalling pathways, predicting the impact and efficacy of any one signalling inhibitor is difficult. Inhibition of multiple pathways will almost certainly be required to substantially affect ovarian cancer growth.

-

Effective methods for early detection are needed. Given the prevalence of ovarian cancer, strategies for early detection must have a high sensitivity for early-stage disease (>75%), but an extremely high specificity (99.6%) to attain a positive predictive value of at least 10% (ten operations for each case of ovarian cancer). Using rising values of serum biomarkers such as CA125 to trigger transvaginal sonography is a promising approach.

Abstract

Over the past two decades, the 5-year survival for ovarian cancer patients has substantially improved owing to more effective surgery and treatment with empirically optimized combinations of cytotoxic drugs, but the overall cure rate remains approximately 30%. Many investigators think that further empirical trials using combinations of conventional agents are likely to produce only modest incremental improvements in outcome. Given the heterogeneity of this disease, increases in long-term survival might be achieved by translating recent insights at the molecular and cellular levels to personalize individual strategies for treatment and to optimize early detection.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Goff, B. A. et al. Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer 89, 2068 (2000).

Zebrowski, B. K. et al. Markedly elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in malignant ascites. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 6, 373 (1999).

Mesiano, S., Ferrara, N. & Jaffe, R. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in ovarian cancer: inhibition of ascites formation by immunoneutralization. Am. J. Path. 153, 1249 (1998).

Numnum, T. M. et al. The use of bevacizumab to palliate symptomatic ascites in patients with refractory ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 102, 425 (2006).

Berek, J. S. in Practical Gynecologic Oncology 4th edn Ch. 11 Ovarian Cancer (eds Berek, J. S. & Hacker, N. F.) 443–511 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2005).

Armstrong, D. K. et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 34–43 (2006).

Feeley, K. M. & Wells, M. Precursor lesions of ovarian epithelial malignancy. Histopathology 38, 87 (2001).

Zhang, S. et al. Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res. 68, 4311–4320 (2008). This report established the phenotype of tumour-initiating ovarian cancer cells.

Alvero, A. B. et al. Molecular phenotyping of human ovarian cancer stem cells unravel the mechanisms for repair and chemoresistance. Cell Cycle 8, 188–169 (2009).

Jacobs, I. J. et al. Clonal origin of epithelial ovarian cancer: analysis by loss of heterozygosity, p53 mutation and X chromosome inactivation. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 84, 1793–1798 (1992).

Bast, R. C. Jr & Mills, G. B. in The Molecular Basis of Cancer 3rd edn (eds Mendelsohn, J., Howley, P., Israel, M., Gray, J. & Thompson, C. ) 441–455 (W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 2008).

Iwabuchi, H. et al. Genetic analysis of benign, low-grade and high-grade ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 55, 6172–6180 (1995).

Risch, H. A. et al. Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 98, 1675–1677 (2006).

Cramer, D. W. et al. Genital talc exposure and risk of ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 81, 351–356 (1999).

Muscat, J. E. & Huncharek, M. S. Perineal talc use and ovarian cancer: a critical review. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 62, 358–360 (2006).

Kohler, M. F. et al. Spectrum of mutation and frequency of allelic deletion of the p53 gene in ovarian cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 85, 1513–1519 (1993). This paper indicated that ovarian cancers undergo spontaneous mutation.

Berchuck, A. et al. Overexpression of p53 is not a feature of benign and early-stage borderline epithelial ovarian tumors. Gynecol. Oncol. 52, 232–236 (1994).

Berchuck, A. et al. The p53 tumor suppressor gene frequently is altered in gynecologic cancers. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 170, 246–252 (1994).

Havrilesky, L. et al., Prognostic significance of p53 mutation and p53 overexpression in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 3814–3825 (2003).

Hall, J. et al. Critical evaluation of p53 as a prognostic marker in ovarian cancer. Exp. Rev. Mol. Med. 12, 1–20 (2004). A thoughtful and thorough review of the prognostic significance of p53 in ovarian cancer.

Buller, R. E. et al. A phase I/II trial of rAd/p53 (SCH58500) gene replacement in recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 9, 553–566 (2002).

Vasey, P. A. et al. Phase I trial of intraperitoneal injection of the E1B-55-kd-gene-deleted adenovirus ONYX-015 (dl1520) given on days 1 through 5 every 3 weeks in patients with recurrent/refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 1562–1569 (2002).

Kojima, K. et al. MDM2 antagonists induce p53-dependent apoptosis in AML: implications for leukemia therapy. Blood 106, 3150–3159 (2005).

Yu, Y. et al. in Methods in Enzymology: Regulators and Effectors of Small GTPases. Ras Proteins Vol. 407 (eds Balch, W. E., Der, C. & Hall, A.) 455–467 (Academic, New York, 2006). A comprehensive review of the role of DIRAS3 (ARHI) in ovarian cancer.

Cvetkovic, D. et al. Altered expression and loss of heterozygosity of the LOT1 gene in ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 95, 449–455 (2004).

Feng, W. et al. Imprinted tumor suppressor genes ARHI and PEG3 are the most frequently down-regulated in human ovarian cancers by loss of heterozygosity and promoter methylation. Cancer 112, 1489–1502 (2008).

Chen, M. Y. et al. Synergistic inhibition of ovarian cancer cell growth with demethylating agents and histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc. Amer. Assoc. Cancer Res. 681 (2007).

Mackay, H. et al. A phase II trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor belinostat (PSC101) in patients with platinum resistant epithelial ovarian tumors and micropapillary/borderline (LMP) ovarian tumors. A PMH phase II consortium trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (Suppl.) 5518 (2008).

Balch, C. et al. The epigenetics of ovarian cancer drug resistance and resensitization. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 191, 1552–1572 (2004).

Bast, R. C. et al. A phase IIa study of a sequential regimen using azacitidine to reverse platinum resistance to carboplatin in patients with platinum resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (Suppl.) 3500 (2008).

Rubin, S. C. et al. BRCA1, BRCA2, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer gene mutations in an unselected ovarian cancer population: relationship to family history and implications for genetic testing. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 178, 670–677 (1998).

Lancaster, J. M. et al. BRCA2 mutations in primary breast and ovarian cancers. Nature Genet. 13, 238–240 (1996).

Boyd, J. in Ovarian Cancer 5 (eds Sharp, F., Blackett, T., Berek, J. & Bast, R.) 3–16 (Isis Medical Media, Oxford, 1998).

Chetrit, A., Hirsh-Yechezkel, G., Ben-David, Y., Lubin, F. & Friedman, E. Effect of BRCA 1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 20–25 (2008).

Moynahan, M. E. et al. Homology directed DNA repair, mitomycin-c resistance, and chromosome stability is restored with correction of a Brca1 mutation. Cancer Res. 61, 4842–4850 (2001).

Narod, S. A & Foulkes, W. D. BRCA1 and BRCA2, 1994 and beyond. Nature Rev. Cancer 4, 665–676 (2004).

Edwards, S. L. et al. Resistance to therapy caused by intragenic deletion in BRCA2. Nature 451, 1111–1115 (2008).

Sakai, W. et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of resistance to cisplatin in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature 451, 1116–1120 (2008).

Drew, Y. & Calvert, H. The potential of PARP inhibitors in genetic breast and ovarian cancers. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1138, 126–145 (2008).

Yap, T. A., Carden, C. T. & Kaye, S. B. Beyond chemotherapy: targeted therapies in ovarian cancer. Nature Rev. Cancer 9, 167–181 (2009). A thorough and up-to-date review of molecular therapeutics for ovarian cancer.

Hennessey, B. et al. BRCA status in ovarian cancer. Proc. Amer. Soc. Clin. Oncol. (in the press).

Umayahara, K. et al. in Ovarian Cancer 5 (eds Sharp, F., Blackett, T., Berek, J. & Bast, R.) 17–23 (Isis Medical Media, Oxford, 1998).

Jazaeri, A. A. et al. Gene expression profiles of BRCA1-linked, BRCA2-linked, and sporadic ovarian cancers. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 13, 990–1000 (2002). This provocative paper suggests that sporadic ovarian cancers are either BRCA1 or BRCA2-like.

Eder, A. M. et al. Atypical PKCι contributes to poor prognosis through loss of apical–basal polarity and cyclin E overexpression in ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. USA 102, 12519–12524 (2005).

Zhang, L. et al. MicroRNAs exhibit high frequency genomic alterations in human cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9136–9141 (2003).

Tangir, J. et al. Frequent microsatellite instability in epithelial borderline ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 56, 2501–2505 (1996).

Rodabaugh, K. J. et al. Detailed deletion mapping of chromosome 9p and p16 gene alterations in human borderline and invasive epithelial ovarian tumors. Oncogene 11, 1249–1254 (1995).

Berchuck, A. et al. Overexpression of p53 is not a feature of benign and early- stage borderline epithelial ovarian tumors. Gynecol. Oncol. 52, 232–236 (1994).

Iwabuchi, H. et al. Genetic analysis of benign, low-grade, and high-grade ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 55, 6172–6180 (1995).

Abu-Jawdeh, G. M. et al. Estrogen receptor expression is a common feature of ovarian borderline tumors. Gynecol. Oncol. 60, 301–307 (1996).

Liu, J. et al. A genetically defined model for human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 64, 1655–1663 (2004). This paper showed that an ovarian phenotype can be induced in xenografts by transfecting normal human ovarian surface epithelial cells with SV40 T antigen, telomerase and mutant Ras.

Cheng, K. W. et al. Emerging role of Rab GTPases in cancer and human disease. Cancer Res. 65, 2516–2519 (2005).

Gautschi, O. et al. Aurora kinases as cancer drug targets. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1639–1648 (2008).

Li, K. et al. Modulation of Notch signaling by antibodies specific for the extracellular regulatory region of Notch3. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8046–8054 (2008).

Schilder, R. J, et al. Phase II study of gefitinib in patients with relapsed or persistent ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma and evaluation of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and immunohistochemical expression: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 5539–5548 (2005).

Gordon, A. N. et al. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib HCI, an epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1/EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: results from a phase II multicenter study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 15, 785–792 (2005).

Heinemann, V., Stintzing, S., Kirchner, T., Boeck, S. & Jung, A. Clinical relevance of EGFR- and KRAS-status in colorectal cancer patients treated with monoclonal antibodies directed against the EGFR. Cancer Treat. Rev. 35, 262–271 (2009).

Bookman, M. A. et al. Evaluation of monoclonal humanized anti-HER2 antibody, trastuzumab, in patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma with overexpression of HER2: a phase II trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 283–290 (2003).

Hu, L., Hofmann, J., Lu, Y., Mills, G. B. & Jaffe, R. B. Inhibition of phophatidylinositol 3′ kinase increases efficacy of paclitaxel in in vitro and in vivo ovarian cancer models. Cancer Res. 62, 1087–1092 (2002).

Raynaud, F. L. et al. Pharmacologic characterization of a potent inhibitor of class I phophatidylinositide 3-kinases. Cancer Res. 67, 5840–5850 (2007).

Rosen, D. G. et al. The role of constitutively active signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in ovarian tumorigenesis and prognosis. Cancer 107, 2730–2740 (2006).

Burke, W. M. et al. Inhibition of constitutively active Stat3 suppresses growth of human ovarian and breast cancer cells. Oncogene 20, 7925–7934 (2001).

Duan, Z. et al. 8-benzyl-4-oxo-8-azabicyclo[3.2.1]oct-2-ene-6, 7-dicarboxylic acid (SD-1008), a novel janus kinase 2 inhibitor, increases chemotherapy sensitivity in human ovarian cancer cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 1137–1145 (2007).

McMurray, J. S. A new small molecule Stat 3 inhibitor. Chem. Biol. 13, 1123–1124 (2006).

Murph, M. et al. Of spiders and crabs: the emergence of lysophospholipids and their metabolic pathways as targets for therapy in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 6598–6602 (2006).

Beck, H. P. et al. Discovery of potent LPA2 (EDG4) antagonists as potential anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 1037–1041 (2008).

Lin, Y. G. et al. Curcumin inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in ovarian carcinoma by targeting the nuclear factor-κB pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 3423–3430 (2007).

Samanta, A. K, Huang, H. J, Bast, R. C. Jr & Liao, W. Overexpression of MEKK3 confers resistance to apoptosis through activation of NFκB. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7576–7583 (2004).

Häcker, H. & Karin, M. Regulation and function of IKK and IKK-related kinases. Science STKE 357, re 13 (2006).

Yang, J. et al. The essential role of MEKK3 in TNF-induced NF-κB activation. Nature Immunol. 2, 620–624 (2001).

Karin, M. Nuclear factor κB in cancer development and progression. Nature 441, 431–436 (2006).

See, H. T., Kavanagh, J. J., Hu, W. & Bast, R. C. Jr. Targeted therapy for epithelial ovarian cancer: current status and future prospects. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 13, 701–734 (2004).

Suh, D. S., Yoon, M. S., Choi, K. U. & Kim, J. Y. Significance of E2F-1 overexpression in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 18, 492–498 (2008).

Reimer, D. et al. Expression of the E2 family of transcription factors and its clinical relevance in ovarian cancer. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1091, 270–286 (2006).

Berchuck, A. et al. Regulation of growth of normal ovarian epithelial cells and ovarian cancer cell lines by transforming growth factor-β. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 166, 676–684 (1992).

Sunde, J. S. et al. Expression profiling identifies altered expression of genes that contribute to the inhibition of transforming growth factor-β signaling in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 8404–8412 (2006).

Fuller, A. F. Jr, Guy, S., Budzik, G. P. & Donahoe, P. K. Mullerian inhibiting substance inhibits colony growth of a human ovarian carcinoma cell line. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 54, 1051–1055 (1982).

Szotek, P. P. et al. Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Mullerian inhibiting substance responsiveness. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11154–11159 (2006).

Pieretti-Vanmarcke, R. et al. Mullerian inhibiting substance enhances subclinical doses of chemotherapeutic agents to inhibit human and mouse ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17426–17431 (2006).

Reed, J. et al. Significance of Fas receptor protein expression in epithelial ovarian cancer. Hum. Pathol. 36, 971–976 (2005).

Kar, R. et al. Role of apoptotic regulators in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 6, 1101–1105 (2007).

Schuyer, M. et al. Reduced expression of BAX is associated with poor prognosis in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a multifactorial analysis of TP53, p21, BAX and BCL-2. Br. J. Cancer 85, 1359–1367 (2001).

Lancaster, J. M. et al. High expression of tumor necrosis factor apoptosis- inducing ligand is associated with favorable ovarian cancer survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 762–766 (2003).

De la Torre, F. J. et al. Apoptosis in epithelial ovarian tumours: prognostic significance of clinical and histopathologic factors and its association with the immunohistochemical expression of apoptotic regulatory proteins (p53, bcl-2 and bax). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 130, 121–128 (2007).

Liang, X. H. et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 402, 672–676 (1999).

Lu, Z. et al. A novel tumor suppressor gene ARHI induces autophagy and tumor dormancy in ovarian cancer xenografts. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3917–3929 (2008). The initial report that linked autophagy and tumour dormancy.

Ren, J. et al. Lysophosphatidic acid is constitutively produced by human peritoneal mesothelial cells and enhances adhesion, migration, and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 15, 3006–3014 (2006).

Fishman, D. A. et al. Lysophosphatidic acid promotes matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation and MMP-dependent invasion in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1, 3194–3199 (2001).

Fang, X. et al. Mechanisms for lysophosphatidic acid-induced cytokine production in ovarian cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9653–9661 (2004).

Sood A, K. et al. Stress hormone-mediated invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 369–375 (2006). This report links stress to ovarian cancer growth through physiological mechanisms.

Barbolina, M. V. et al. Microenvironmental regulation of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase activity in ovarian carcinoma cells via collagen-induced EGR1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 16, 4924–4931 (2007).

Cai, K. Q. et al. Prominent expression of metalloproteinases in early stages of ovarian tumorigenesis. Mol. Carcinog. 46, 130–143 (2007).

Prezas, P. et al. Overexpression of the human tissue kallikrein genes KLK4, 5, 6, and 7 increases the malignant phenotype of ovarian cancer cells. Biol. Chem. 387, 807–811 (2006).

Paliouras, M. et al. Human tissue kallikreins: the cancer biomarker family. Cancer Lett. 28, 61–79 (2007).

Yin, B. W. T. & Lloyd, K. O. Molecular cloning of the CA125 ovarian cancer antigen: identification as a new mucin, MUC16. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27371–27375 (2001).

Gubbels, J. A. et al. Mesothelin–MUC16 binding is a high affinity, N-glycan dependent interaction that facilitates peritoneal metastasis of ovarian tumors. Mol. Cancer 5, 50 (2006).

Rump, A., Morikawa, Y. & Tanaka, M. Binding of ovarian cancer antigen CA125/MUC16 to mesothelin mediates cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9190–9198 (2004).

Cannistra, S. A. et al. CD44 variant expression is a common feature of epithelial ovarian cancer: lack of association with standard prognostic factors. J. Clin. Oncol. 13, 1912–1921 (1995).

Strobel, T., Swanson, L. & Cannistra, S. A. In vivo inhibition of CD44 limits intra-abdominal spread of a human ovarian cancer xenograft in nude mice: a novel role for CD44 in the process of peritoneal implantation. Cancer Res. 57, 1228–1232 (1997).

Yoneda, J. et al. Expression of angiogenesis-related genes and progression of human ovarian carcinomas in nude mice. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 90, 447–454 (1998).

Birrer, M. J. et al. Whole genome oligonucleotide-based array comparative genomic hybridization analysis identified fibroblast growth factor 1 as a prognostic marker for advanced-stage serous ovarian adenocarcinomas. J. Clin Oncol. 1, 2281–2287 (2007). A recent comparative genomic hybridization analysis that indicates the importance of FGF1 in the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer.

Monk, B. J. et al. Salvage bevacizumab (rhuMAB VEGF)-based therapy after multiple prior cytoxic regimens in advanced refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 102, 140–144 (2006).

Kamat, A. A. et al. Metronomic chemotherapy enhances the efficacy of antivascular therapy in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 281–288 (2007).

Lu, C. et al. Impact of vessel maturation on antiangiogenic therapy in ovarian cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 198, 477.e1–477.e9 (2008).

Lin, Y. G. et al. EphA2 overexpression in associated with angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. Cancer 109, 332–340 (2007).

Landen, C. N. et al. Efficacy and antivascular effects of EphA2 reduction with an agonistic antibody in ovarian cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 98, 1558–1570 (2006).

Landen, C. N. et al. Intraperitoneal delivery of liposomal siRNA for therapy of advanced ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 5, 1708–1713 (2006). This paper showed that neutral liposomes allow the efficient delivery of siRNA to human ovarian cancer xenografts.

Mancuso, M. R. et al. Rapid vascular regrowth in tumors after reversal of VEGF inhibition. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 2610–2621 (2006).

Yang, G. et al. The chemokine growth-regulated oncogene 1 (Gro-1) links RAS signaling to the senescence of stromal fibroblasts and ovarian tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 31, 16472–16477 (2006).

Milliken, D. et al. Analysis of chemokines and chemokine receptor expression in ovarian cancer ascites. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 1108–1114 (2002).

Zhang, L. et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 16, 203–213 (2003). A thorough study that documents the prognostic significance of T cell infiltration in ovarian cancer.

Sato, E. et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18538–18543 (2005).

Jiang, Y. P. et al. Expression of chemokine CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 in human epithelial ovarian cancer: an independent prognostic factor for tumor progression. Gynecol. Oncol. 103, 226–233 (2006).

Kryczek, I. et al. CXCL12 and vascular endothelial growth factor synergistically induce neoangiogenesis in human ovarian cancers. Cancer Res. 65, 465–472 (2005).

Curiel, T. J. et al. Dendritic cell subsets differentially regulate angiogenesis in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 64, 5535–5538 (2004).

Kajiyana, H. et al. Involvement of SDF-1α/CXCR4 axis in the enhanced peritoneal metastasis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 122, 91–99 (2008).

Szosarek, P. W. et al. Expression and regulation of tumor necrosis factor α in normal and malignant ovarian epithelium. Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 382–390 (2006).

Kulbe, H. et al. The inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α generates an autocrine tumor-promoting network in epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 67, 585–592 (2007).

Madhusdan, S. et al. Study of etanercept, a tumor necrosis α inhibitor, in recurrent ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 5950–5959 (2005).

Rustin, G. J. S. et al. Use of CA-125 in clinical trial evaluation of new therapeutic drugs for ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3919–3926 (2004). A recent review regarding the application of CA125 to clinical trials.

Menon, U. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Lancet Oncol. 10, 327–340 (2009). Initial data from this trial suggest that combining CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound will be an effective strategy for the early detection of ovarian cancer.

Das, P. M. & Bast, R. C Jr. Early detection of ovarian cancer. Biomarkers Med. 2, 291–303 (2008).

Bouchard, D. et al. Proteins with whey-acidic protein motifs and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 7, 167–174 (2006).

Lu, K. H. et al. Selection of potential markers for epithelial ovarian cancer with gene expression arrays and recursive descent partition analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3291–3300 (2004).

Clarke, C. H. et al. A panel of proteomic markers improves the sensitivity of CA125 for detecting stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (Suppl.) 5542 (2008).

Bast, R. C. et al. Optimizing a two-stage strategy for early detection of ovarian cancer. NCI Translational Science Meeting 300, #292. National Cancer Institute [online] (2008).

Shridhar, V., et al. Genetic analysis of early- versus late-stage ovarian tumors. Cancer Res. 61, 5895–5904 (2001).

Marquez, R. T. et al. Patterns of gene expression in different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer correlate with those in normal fallopian tube, endometrium and colon. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 6116 (2005). This study showed that the gene expression profiles of different ovarian cancer histotypes correlate with their morphological counterparts in normal tissues.

Cheng, W. et al. Lineage infidelity of epithelial ovarian cancers is controlled by HOX genes that specify regional identity in the reproductive tract. Nature Med. 11, 531 (2005). The authors make a convincing argument that the HOX genes have a role in determining ovarian cancer histotypes.

Tothill, R. W. et al. Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 5198–5208 (2008).

Schwartz, D. R. et al. Gene expression in ovarian cancer reflects both morphology and biological behavior, distinguishing clear cell from other poor-prognosis ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 63, 4722–4729 (2002).

Kurman R. J. & Shih, L. E. M. Pathogenesis of ovarian cancer: lessons from morphology and biology and their clinical implications. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 27, 151–160 (2008). This review summarizes the evidence for type I and type II ovarian cancer.

Bast, R. C. Jr et al. A radioimmunoassay using a monoclonal antibody to monitor the course of epithelial ovarian cancer. New Engl. J. Med. 309, 883–887 (1983). This is the original report of the CA125 assay.

Spaeth, E. L. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell transition to tumor-associated fibroblasts contribures to fibrovascular network expansion and tumor progression. PLoS ONE 4, e4992 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the M. D. Anderson Ovarian SPORE National Cancer Institutes (P50CA83639), the National Foundation for Cancer Research, the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund, the Mossy Foundation and the Zarrow Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

National Cancer Institute Drug Dictionary

FURTHER INFORMATION

Glossary

- Intercurrent infection

-

An infection that occurs at the same time as a patient is suffering from a different disease.

- Endometriosis

-

The growth of tissue that resembles the endometrium in areas within the pelvic cavity.

- Loss of heterozygosity

-

(LOH). In cells that carry a mutated allele of a tumour suppressor gene, the gene becomes fully inactivated when the cell loses a large part of the chromosome that carries the wild-type allele. Regions with a high frequency of LOH are thought to contain tumour suppressor genes.

- Metronomic chemotherapy

-

The frequent, chronic administration of chemotherapy at low, non-toxic doses, with no prolonged drug-free breaks.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bast, R., Hennessy, B. & Mills, G. The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for translation. Nat Rev Cancer 9, 415–428 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2644

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2644

This article is cited by

-

Tropomyosin1 isoforms underlie epithelial to mesenchymal plasticity, metastatic dissemination, and resistance to chemotherapy in high-grade serous ovarian cancer

Cell Death & Differentiation (2024)

-

Identification and validation of m5c-related lncRNA risk model for ovarian cancer

Journal of Ovarian Research (2023)

-

Development and validation of an individualized gene expression-based signature to predict overall survival of patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma

European Journal of Medical Research (2023)

-

Advanced stage, high-grade primary tumor ovarian cancer: a multi-omics dissection and biomarker prediction process

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Polyploidy, EZH2 upregulation, and transformation in cytomegalovirus-infected human ovarian epithelial cells

Oncogene (2023)