Abstract

Magnetic reconnection is a fundamental process in solar system and astrophysical plasmas, through which stored magnetic energy associated with current sheets is converted into thermal, kinetic and wave energy1,2,3,4. Magnetic reconnection is also thought to be a key process involved in shedding internally produced plasma from the giant magnetospheres at Jupiter and Saturn through topological reconfiguration of the magnetic field5,6. The region where magnetic fields reconnect is known as the diffusion region and in this letter we report on the first encounter of the Cassini spacecraft with a diffusion region in Saturn’s magnetotail. The data also show evidence of magnetic reconnection over a period of 19 h revealing that reconnection can, in fact, act for prolonged intervals in a rapidly rotating magnetosphere. We show that reconnection can be a significant pathway for internal plasma loss at Saturn6. This counters the view of reconnection as a transient method of internal plasma loss at Saturn5,7. These results, although directly relating to the magnetosphere of Saturn, have applications in the understanding of other rapidly rotating magnetospheres, including that of Jupiter and other astrophysical bodies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Since the discovery of H2O plumes from the icy moon Enceladus it has become clear that the dominant source of plasma in Saturn’s magnetosphere is the ionization of neutral molecules deep within the magnetosphere, producing a plasma composed of H2O+, H3O+ and OH+, collectively referred to as the water group, W+ (refs 8,9,10). Some of this plasma is lost from the system by charge exchange; the remaining plasma is transported radially outward. The radial transport is driven by the centrifugal interchange instability, which is analogous to the Rayleigh–Taylor instability with gravity replaced by the centrifugal force associated with the rapid rotation of the magnetosphere6.

Magnetic reconnection is a process involving topological rearrangement of the magnetic field. Generally this involves either connecting planetary magnetic field lines with the solar wind, known as ‘opening’ magnetic flux, on the dayside boundary of the magnetosphere, or reconnection in the magnetotail on the nightside of the planet that reconnects planetary magnetic field lines to each other, known as ‘closing’ magnetic flux. This should also result in mass loss from the magnetosphere. In a time-averaged sense the outward plasma transport rate should match the plasma loss rate, and the dayside reconnection rate should match that in the magnetotail. Observations of reconnection in the magnetotail can thus provide a method to test the loss process for this internally produced plasma, as well as the closure of magnetic flux opened on the dayside.

Data from the Cassini spacecraft have provided only indirect evidence for reconnection in the magnetotail7,11,12,13 and the actual region where magnetic fields are merging, known as the diffusion region, has not been detected at Saturn or Jupiter. The diffusion region has a two-scale structure with the larger ion diffusion region surrounding the smaller electron diffusion region. The ion diffusion region has been detected in observations in Earth’s magnetotail1,14,15, Earth’s magnetosheath16, and at Mars17,18. The plasma loss rates inferred from previous observations of magnetic reconnection at Saturn and Jupiter are an order of magnitude too small when compared with the known plasma production rates5,7,19. Here we report the first observations of an ion diffusion region in Saturn’s magnetotail. These direct observations show that reconnection can occur over prolonged intervals, almost an order of magnitude longer than the longest previously reported20.

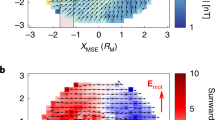

Figure 1 shows magnetic field and electron data for a six hour interval on 8 October 2006 when Cassini was located in the post-midnight sector of Saturn’s magnetosphere around 1:30 Saturn local time, about 8° north of Saturn’s equatorial plane, and at a radial distance of 29 RS, where 1 RS = 60,268 km. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the magnetic field in the tail is generally swept-back into an Archimedean configuration as the result of outward plasma transport and angular momentum conservation. This effect is removed by rotating the data into a new coordinate system where the background magnetic field is in the X direction, and the Y direction is perpendicular to the plane of the swept-back magnetic field (details of the transformation are given in the Supplementary Methods). At the beginning of the interval, Cassini was located above the magnetotail current sheet (Bx > 0), crossing below (Bx < 0) the centre of the current sheet between 3:30 UT–3:40 UT. Bz is ordinarily expected to be negative, as shown in the Supplementary Methods. At 3:55 UT Bz reverses sign, which in fact corresponds to Cassini crossing the X-line from the tailward to the planetward side as shown in Fig. 2. The quantity |Bz|/ max(|Bx|) is an estimate of the reconnection rate and was found to be 0.13 ± 0.10 with a peak of 0.66—hence consistent with fast magnetic reconnection16.

a, Electron omnidirectional flux time–energy spectrogram in units of differential energy flux (eV m−2 sr−1 s−1 eV−1). b–d, Three components of the magnetic field in the X-line coordinate system; the parts of the Bx and By traces in red (blue) show where the By component is expected to be positive (negative). e, The field magnitude.

The red vectors show the original spherical polar coordinate system from the magnetometer data and the green vectors show the new X-line coordinate system that takes into account the swept-back configuration of the magnetic field. The blue curve in the top two panels shows the orbit of Cassini around Saturn and in the bottom view we show a simplified sketch of the inferred motion of Cassini relative to the magnetic reconnection X-line. The pink and blue regions are the ion and electron diffusion regions9.

On the tailward side of the X-line a very energetic (∼10 keV q−1) ion population is observed flowing tailward, and slightly duskward. This population is not a field-aligned ion beam and has a significant perpendicular velocity component. These ions are moving with speeds of 1,200 km s−1, a substantial fraction of the Alfvén speed of ∼4,000 km s−1 outside the current sheet21 and much larger than the speed of plasma azimuthally moving around the planet (∼150 km s−1), and are identified as the tailward jet from the diffusion region. On the planetward side of the diffusion region the field-of-view of the ion detector does not cover the region where we would expect to see planetward ion beams. Later that day as Cassini leaves the diffusion region the plasma flow returns to near azimuthal motion, but with a tailward and northward component. Detailed analyses of these ion flow directions are presented in the Supplementary Methods.

Around the magnetic reconnection site ideal magnetohydrodynamics breaks down and charged particles become demagnetized from the magnetic field. As a result of a factor of ∼1,800 in the mass difference between electrons and ions, the ions demagnetize over a larger spatial region than electrons resulting in differential motion between ions and electrons. The resulting current system is known as the Hall current system and produces a characteristic quadrupolar magnetic field structure in the out-of-plane magnetic field, By (Fig. 2). In the ion diffusion region on the tailward side of the diffusion region Bx and By have the same sign but on the planetward side of the X-line Bx and By have opposite signs15. Hence, the sign of By can be predicted on the basis of the value of Bx and Bz thus providing a test for the presence of the Hall magnetic field. The red (blue) regions of Bx and By in Fig. 1 indicate where the By component is expected to have a positive (negative) sign associated with this current system and this colour coding is consistent with the Hall field.

As expected, the strength of the Hall field perturbation peaks between the centre and exterior of the current sheet. Three of the four quadrants of the Hall field were measured by Cassini, as indicated by the simplified sketch of Cassini’s trajectory in Fig. 2, based on the data in Fig. 1. As calculated in the Supplementary Methods, the strength of the Hall field can be estimated by the quantity |By|/ max(|Bx|) and the mean value of 0.18 ± 0.15 is smaller than that observed in other environments although the peak of 0.83 is more consistent with the typical strength, ∼0.5, of the Hall field1,18.

As shown in the Supplementary Methods, further evidence for the detection of the ion diffusion region is cool ∼100 eV electrons flowing in response to the Hall current system, and hot ∼1–10 keV electrons flowing out of the diffusion region. Small loop-like magnetic field structures at 2:20–3:00 UT and 3:28–3:40 UT also represent evidence for ongoing reconnection. Taken together, the conclusion is that Cassini encountered a tailward moving ion diffusion region in Saturn’s magnetotail as sketched in Fig. 2.

In two-fluid magnetic reconnection theory the size of the ion diffusion region is a multiple of the ion inertial length, c/ωi, where c is the speed of light in a vacuum and ωi is the ion plasma frequency given by (nZ2e2/ɛ0mi)1/2, where n is the ion number density, Z is the ion charge state, e is the fundamental charge, ɛ0 is the permittivity of free space, and mi is the ion mass. Using measurements of magnetotail plasma at 30 RS with a plasma number density of 4–8 × 104 m−3 and composition22 of nW+/nH+ ∼ 2, the mean ion mass is 1.95 × 10−26 kg and the ion inertial length is 3,000–4,000 km (0.05–0.06 RS); hence, the ion diffusion region at Saturn should be >∼0.06 RS (4,000 km) in thickness. The lower plasma density in the Saturnian system means that the ion diffusion region is an order of magnitude larger than at Earth. Cassini spends over 150 min near the reconnection site, which although longer than the ∼10 min at Earth, is not unexpected given the differing size of the diffusion region itself.

Plasmoids are loops of magnetic flux produced as part of the reconnection process and they have been used to estimate7 magnetic flux closure in the magnetotail by integrating the product of the Bθ component of the magnetic field and the tailward flow speed. This has shown rates of magnetic flux closure between 0.0029 and 0.024 GWb/RS, where the dimensions include per unit length because the cross-tail length of the diffusion region is unknown and there is no evidence for large reconnection events that extend the full width of the magnetotail.

Applying the same argument to the data in the ion diffusion region in Fig. 1, between 1:46 and 3:55 UT, and a flow speed of 1,200 km s−1 (based on the ion measurements), the reconnected flux is 0.34 GWb RS−1 over a 2 h period. This is more than an order of magnitude greater than the largest estimates based on plasmoid observations alone7. From changes in the size of Saturn’s main auroral oval, changes in open tail flux are typically 5 GWb over a 10–60 h period23 but, occasionally, can be much higher (3.5 GWb h−1; ref. 24). Our observations are entirely consistent with rates of flux closure inferred from auroral observations, requiring only modest ∼10% fractions of the tail width to be involved.

Estimates of the mass lost per plasmoid can be made by combining the typical tail plasma density of ∼104 m−3 of 18 AMU per ion plasma, with an estimate for the plasmoid volume of 10RS3, to give 62 × 103 kg per plasmoid. Hence, ∼200 plasmoids per day (one every ∼7 min) are required to remove the plasma transported outwards from the inner magnetosphere5. By scaling our calculated rate of flux closure by the mass per unit magnetic flux22 of ∼10−3 kg Wb−1, we estimate that this releases 3 × 105 kg RS−1 or 3 × 107 kg, three orders of magnitude larger than previous estimates based on plasmoids20. Events of this magnitude every ∼4–40 days are required to match a time-averaged mass loading rate of 100 kg s−1, rather than every 7 min from previous estimates based on indirect observations5. Hence, these results demonstrate that magnetotail reconnection can close sufficient amounts of magnetic flux and act as a very significant mass loss mechanism.

Additional indirect signatures of magnetic reconnection are also observed two hours after the diffusion region moves tailward. Figure 3 shows five hours of electron fluxes and magnetometer data (Kronocentric radial–theta–phi, KRTP) revealing a series of reconnection signatures in a spherical polar coordinate system. Bipolar perturbations in the Bθ component indicate the passage of a loop-like magnetic flux structure and the sense of the perturbation indicates the direction of travel; that is, a negative–positive perturbation is moving tailward7. At 6:10 UT a tailward-moving loop passes near the spacecraft, sourced from a diffusion region planetward of the spacecraft. At 7:05 and 8:10 UT a sharp increase in Bθ to large positive values is indicative of the compression of magnetic field lines around plasma moving rapidly towards the planet as the result of magnetic reconnection downtail from the spacecraft25. These are known as dipolarization fronts and they indicate the presence of a diffusion region tailward of the spacecraft. Following the passage of the fronts the spacecraft is immersed in hot plasma, similar to that seen in Earth’s magnetotail26, and this is a signature of the energy conversion in the reconnection process. After the final dipolarization front passes Cassini, the spacecraft is located in a region of fluctuating magnetic fields similar to a chain of magnetic islands (loops) and is surrounded by energetic ∼10 keV electrons27 that from 8:10 to 9:10 UT also exhibit evidence of becoming more energetic with time. Ion flows with a planetward component are found throughout this hot plasma region with speeds in excess of ∼1,000 km s−1. Towards the end of the interval, between 15:00 and 17:25 UT, planetward-flowing ions and electrons are found in a layer between the centre of the current sheet and its exterior, which are consistent with outflows from a more distant diffusion region28. The detailed particle analysis is presented in the Supplementary Methods.

a, Electron omnidirectional flux time–energy spectrogram in units of differential energy flux (eV m−2 sr−1 s−1 eV−1). b–d, Three components of the magnetic field in spherical polar coordinates. e, The magnetic field strength. The grey region indicates periods where the spacecraft is immersed in the plasma sheet.

These data are evidence for ongoing but time-variable magnetic reconnection in the magnetotail at this local time over a period of 19 h, covering almost two rotations of Saturn. Simulations of upstream solar wind conditions presented in the Supplementary Methods show that the magnetosphere was strongly compressed just before the entry into the diffusion region, suggesting triggering of tail reconnection by a solar wind pressure pulse. As shown in the Supplementary Methods, a weaker pressure pulse arrives on 9 October at 14:00 UT when Cassini was located in the inner magnetosphere. Wave signatures suggest that this triggered further reconnection. These observations stand in contrast to the much less frequent plasmoid observations that have previously been used to infer rates of magnetic reconnection in Saturn’s magnetotail. At this point it is not possible to determine whether this is a consequence of the magnitude of the solar wind pressure increase, or if this is simply a common event but rarely observed owing to the orbit of Cassini and the spatial distribution/spatial size of diffusion regions. These results show that prolonged magnetotail reconnection can close sufficient magnetic flux and shed sufficient mass to explain the time-averaged driving of Saturn’s magnetosphere.

References

Øieroset, M., Phan, T. D., Fujimoto, M., Lin, R. P. & Lepping, R. P. In situ detection of collisionless reconnection in the Earth’s magnetotail. Nature 412, 414–417 (2001).

Eastwood, J. P. et al. Evidence for collisionless magnetic reconnection at Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L02106 (2008).

Chen, L.-J. et al. Observation of energetic electrons within magnetic islands. Nature Phys. 4, 19–23 (2008).

Angelopoulos, V. et al. Electromagnetic energy conversion at reconnection fronts. Science 341, 1478–1482 (2013).

Bagenal, F. & Delamere, P. A. Flow of mass and energy in the magnetospheres of Jupiter and Saturn. J. Geophys. Res. 116, A05209 (2011).

Thomsen, M. F. Saturn’s magnetospheric dynamics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 5337–5344 (2013).

Jackman, C. M. et al. Saturn’s dynamic magnetotail: A comprehensive magnetic field and plasma survey of plasmoids and traveling compression regions and their role in global magnetospheric dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 5465–5495 (2014).

Jurac, S. & Richardson, J. D. A self-consistent model of plasma and neutrals at Saturn: Neutral cloud morphology. J. Geophys. Res. 110, A09220 (2005).

Hansen, C. J. et al. Enceladus water vapour plume. Science 311, 1422–1425 (2006).

Fleshman, B. L., Delamere, P. A. & Bagenal, F. A sensitivity study of the Enceladus torus. J. Geophys. Res. 115, E04007 (2010).

Jackman, C. M. et al. Strong rapid dipolarizations in Saturn’s magnetotail: In situ evidence of reconnection. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L11203 (2007).

Hill, T. W. et al. Plasmoids in Saturn’s magnetotail. J. Geophys. Res. 113, A01214 (2008).

Mitchell, D. G. et al. Energetic ion acceleration in Saturn’s magnetotail: Substorms at Saturn? Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L20S01 (2005).

Nagai, T. et al. Geotail observations of the Hall current system: Evidence of magnetic reconnection in the magnetotail. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 25929–25949 (2001).

Eastwood, J. P., Phan, T. D., Øieroset, M. & Shay, M. A. Average properties of the magnetic reconnection ion diffusion region in the Earth’s magnetotail: The 2001–2005 Cluster observations and comparison with simulations. J. Geophys. Res. 115, A08215 (2010).

Phan, T. D. et al. Evidence for magnetic reconnection initiated in the magnetosheath. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L14104 (2007).

Eastwood, J. P. et al. Evidence for collisionless magnetic reconnection at Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L02106 (2008).

Halekas, J. S. et al. In situ observations of reconnection Hall magnetic fields at Mars: Evidence for ion diffusion region encounters. J. Geophys. Res. 114, A11204 (2009).

Vogt, M. F. et al. Structure and statistical properties of plasmoids in Jupiter’s magnetotail. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 821–843 (2014).

Thomsen, M. F., Wilson, R. J., Tokar, R. L., Reisenfeld, D. B. & Jackman, C. M. Cassini/CAPS observations of duskside tail dynamics at Saturn. J. Geophys. Res. 118, 5767–5781 (2013).

Arridge, C. S. et al. Plasma electrons in Saturn’s magnetotail: Structure, distribution and energisation. Planet. Space Sci. 57, 2032–2047 (2009).

McAndrews, H. J. et al. Plasma in Saturn’s nightside magnetosphere and the implications for global circulation. Planet. Space Sci. 57, 1714–1722 (2009).

Badman, S. V., Jackman, C. M., Nichols, J. D., Clarke, J. T. & Gérard, J.-C. Open flux in Saturn’s magnetosphere. Icarus 231, 137–145 (2014).

Radioti, A. et al. Saturn’s elusive nightside polar arc. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 6321–6328 (2014).

Runov, A. et al. A THEMIS multicase study of dipolarization fronts in the magnetotail plasma sheet. J. Geophys. Res. 116, A05216 (2011).

Angelopoulos, V. et al. Electromagnetic energy conversion at reconnection fronts. Science 341, 1478–1482 (2013).

Chen, L.-J. et al. Observation of energetic electrons within magnetic islands. Nature Phys. 4, 19–23 (2008).

Onsager, T. G., Thomsen, M. F., Gosling, J. T. & Bame, S. J. Electron distributions in the plasma sheet boundary layer: Time-of-flight effects. Geophys. Res. Lett. 17, 1837–1840 (1990).

Acknowledgements

C.S.A. was financially supported in this work by a Royal Society Research Fellowship. C.M.J. was financially supported by an STFC Ernest Rutherford Fellowship. M.F.T. was supported by the NASA Cassini programme through JPL contract 1243218 with Southwest Research Institute and is grateful to Los Alamos National Laboratory for support provided to her as a guest scientist. J.P.E. and M.K.D. were supported by STFC grant ST/K001051/1. C.S.A., C.M.J., J.A.S., N.A., X.J., A.K., A.R., M.V. and A.P.W. acknowledge the support of the International Space Science Institute where part of this work was carried out. Cassini operations are supported by NASA (managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory) and ESA. The data reported in this paper are available from the NASA Planetary Data System http://pds.jpl.nasa.gov. SKR data were accessed through the Cassini/RPWS/HFR data server http://www.lesia.obspm.fr/kronos developed at the Observatory of Paris/LESIA with support from CNRS and CNES. Solar wind simulation results have been provided by the Community Coordinated Modeling Center at Goddard Space Flight Center through their public Runs on Request system (http://ccmc.gsfc.nasa.gov). The CCMC is a multi-agency partnership between NASA, AFMC, AFOSR, AFRL, AFWA, NOAA, NSF and ONR. The ENLIL Model was developed by D. Odstrcil at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.A. identified the event in the Cassini data and led the analysis. J.P.E., C.M.J., J.A.S., G.-K.P., M.F.T. and N.S. provided detailed assistance with analysis of the magnetic field and particle data. L.L. and P.Z. analysed the Cassini radio and plasma wave data and provided an interpretation of the kilometric radiation data. N.A., X.J., A.K., A.R., M.V. and A.P.W. discussed the detailed interpretation of the event with C.S.A. and provided additional expertise to clarify the interpretation and its wider significance. D.B.R. developed software used to fit CAPS time-of-flight spectra. A.J.C. and M.K.D. provided Cassini CAPS/ELS and MAG and oversaw data processing/science planning. All authors participated in writing the manuscript and the Supplementary Methods.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information (PDF 6184 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arridge, C., Eastwood, J., Jackman, C. et al. Cassini in situ observations of long-duration magnetic reconnection in Saturn’s magnetotail. Nature Phys 12, 268–271 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3565

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3565

This article is cited by

-

Missing link found?

Nature Astronomy (2018)

-

Rotationally driven magnetic reconnection in Saturn’s dayside

Nature Astronomy (2018)