Abstract

The comparative study of music and language is drawing an increasing amount of research interest. Like language, music is a human universal involving perceptually discrete elements organized into hierarchically structured sequences. Music and language can thus serve as foils for each other in the study of brain mechanisms underlying complex sound processing, and comparative research can provide novel insights into the functional and neural architecture of both domains. This review focuses on syntax, using recent neuroimaging data and cognitive theory to propose a specific point of convergence between syntactic processing in language and music. This leads to testable predictions, including the prediction that that syntactic comprehension problems in Broca's aphasia are not selective to language but influence music perception as well.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Ivelisse Robles

Kamal Masuta

Kamal Masuta

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brown, C. & Hagoort, P. (eds.) The Neurocognition of Language (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1999).

Peretz, I. & Zatorre, R. (eds.) The Cognitive Neuroscience of Music (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2003).

Lerdahl, F. & Jackendoff, R. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1983).

Peretz, I. & Coltheart, M. Modularity of music processing. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 688–691 (2003).

Tervaniemi, M. et al. Functional specialization of the human auditory cortex in processing phonetic and musical sounds: A magnetoencephalographic (MEG) study. Neuroimage 9, 330–336 (1999).

Patel, A.D., Peretz, I., Tramo, M. & Labrecque, R. Processing prosodic and musical patterns: a neuropsychological investigation. Brain Lang. 61, 123–144 (1998).

Patel, A.D., Gibson, E., Ratner, J., Besson, M., & Holcomb, P.J. Processing syntactic relations in language and music: An event-related potential study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 10, 717–733 (1998).

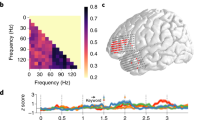

Maess, B., Koelsch, S., Gunter, T. & Friederici, A.D. Musical syntax is processed in Broca's area: an MEG study. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 540–545 (2001).

Tillmann, B., Janata, P. & Bharucha, J.J. Activation of the inferior frontal cortex in musical priming. Cogn. Brain Res. 16, 145–161 (2003).

Koelsch, S. et al. Bach speaks: a cortical “language-network” serves the processing of music. Neuroimage 17, 956–966 (2002).

Luria, A., Tsvetkova, L., & Futer, J. Aphasia in a composer. J. Neurol. Sci. 2, 288–292 (1965).

Peretz, I. Auditory atonalia for melodies. Cognit. Neuropsychol. 10, 21–56 (1993).

Peretz, I. et al. Functional dissociations following bilateral lesions of auditory cortex. Brain 117, 1283–1302 (1994).

Griffiths, T.D. et al. Spatial and temporal auditory processing deficits following right hemisphere infarction. Brain 120, 785–794 (1997).

Ayotte, J., Peretz, I., Rousseau, I., Bard, C., & Bojanowski, M. Patterns of music agnosia associated with middle cerebral artery infarcts. Brain 123, 1926–1938 (2000).

Ayotte, J., Peretz, I. & Hyde, K. Congenital amusia: a group study of adults afflicted with a music-specific disorder. Brain 125, 238–251 (2002).

Nettl, B. An ethnomusicologist contemplates universals in musical sound and musical culture. in The Origins of Music (eds. Wallin, N., Merker, J. & Brown, S.) 463–472 (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000).

Patel, A.D. & Daniele, J.R. An empirical comparison of rhythm in language and music. Cognition 87, B35–B45 (2003).

Deutsch, D. (ed.) The Psychology of Music 2nd edn. (Academic, San Diego, California, 1999).

Jackendoff, R. Foundations of Language (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2002).

Sloboda, J.A. The Musical Mind (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1985).

Gibson, E. & Perlmutter, N.J. Constraints on sentence comprehension. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2, 262–268 (1998).

Swain, J.P. Musical Languages (W.W. Norton, New York, 1997).

Fodor, J.A. Modularity of Mind (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1983).

Elman, J.L. et al. Rethinking Innateness: A Connectionist Perspective on Development (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1996).

Osterhout, L. & Holcomb, P.J. Event-related potentials elicited by syntactic anomaly. J. Mem. Lang. 31, 785–806 (1992).

Frisch, S., Kotz, S.A., Yves von Cramon, D., & Friederici, A.D. Why the P600 is not just a P300: the role of the basal ganglia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114, 336–340 (2003).

Koelsch, S., Gunter, T., Friederici, A.D. & Schröger, E. Brain indices of music processing: 'non-musicians' are musical. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, 520–541 (2000).

Koelsch, S. et al. Differentiating ERAN and MMN: an ERP-study. Neuroreport 12, 1385–1390 (2001).

Chomsky, N. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1965).

Levelt, W.J.M. Models of word production. Trends Cogn. Sci. 3, 223–232 (1999).

Caplan, D. & Waters, G.S. Verbal working memory and sentence comprehension. Behav. Brain Sci. 22, 77–94 (1999).

Ullman, M.T. A neurocognitive perspective on language: the declarative/procedural model. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 717–726 (2001).

Phillips, C. Order and Structure (PhD Thesis, MIT, 1996).

MacDonald, M.C. & Christiansen, M.H. Reassessing working memory: comment on Just and Carpenter (1992) and Waters and Caplan (1996). Psychol. Rev. 109, 35–54 (2002).

Gibson, E. Linguistic complexity: locality of syntactic dependencies. Cognition 68, 1–76 (1998).

Gibson, E. The dependency locality theory: a distance-based theory of linguistic complexity. in Image, Language, Brain (eds. Miyashita, Y., Marantaz, A., & O'Neil, W.) 95–126 (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000).

Babyonyshev, M. & Gibson, E. The complexity of nested structures in Japanese. Language 75, 423–450 (1999).

Lerdahl, F. Tonal Pitch Space (Oxford, Oxford Univ. Press, 2001).

Krumhansl, C.L. Cognitive Foundations of Musical Pitch (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1990).

Krumhansl, C.L. A perceptual analysis of Mozart's piano sonata K. 282: segmentation, tension, and musical ideas. Music Percept. 13, 401–432 (1996).

Bigand, E., & Parncutt, R. Perceiving musical tension in long chord sequences. Psychol. Res. 62, 237–254 (1999).

Bigand, E. Traveling through Lerdahl's tonal pitch space theory: a psychological perspective. Musicae Scientiae 7, 121–140 (2003).

Lerdahl, F. & Krumhansl, C.L. The theory of tonal tension and its implications for musical research. in Los últimos diez años en la investigación musical (eds. Martín Galán, J. & Villar-Taboada, C.) (Valladolid: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Valladolid, in press).

Smith, N. & Cuddy, L.L. Musical dimensions in Beethoven's Waldstein Sonata: An Application of Tonal Pitch Space Theory. Musicae Scientiae (in press).

Vega, D. A perceptual experiment on harmonic tension and melodic attraction in Lerdahls' Tonal Pitch Space. Musicae Scientiae 7, 35–55 (2003).

Warren, T. & Gibson, E. The influence of referential processing on sentence complexity. Cognition 85, 79–112 (2002).

Tillmann, B., Bharucha, J.J. & Bigand, E. Implicit learning of tonality: a self-organizing approach. Psychol. Rev. 107, 885–913 (2000).

Kaan, E. & Swaab, T.Y. The brain circuitry of syntactic comprehension. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6, 350–356 (2002).

Haarmann, H.J. & Kolk, H.H.J. Syntactic priming in Broca's aphasics: evidence for slow activation. Aphasiology 5, 247–263 (1991).

Price, C.J. & Friston, K.J. Cognitive conjunction: a new approach to brain activation experiments. Neuroimage 5, 261–270 (1997).

Kaan, E., Harris, T., Gibson, T. & Holcomb, P.J. The P600 as an index of syntactic integration difficulty. Lang. Cogn. Proc. 15, 159–201 (2000).

Marin, O.S.M. & Perry, D.W. Neurologocal aspects of music perception and performance. in The Psychology of Music 2nd edn. (ed. Deutsch, D.) 653–724 (Academic, San Diego, 1999).

Françès, R., Lhermitte, F. & Verdy, M. Le déficit musical des aphasiques. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Appliquée 22, 117–135 (1973).

Bigand, E., Tillmann, B., Poulin, B., D'Adamo, D. & Madurell, F. The effect of harmonic context on phoneme monitoring in vocal music. Cognition 81, B11–20 (2001).

Bonnel, A.-M., Faïta, F., Peretz, I. & Besson, M. Divided attention between lyrics and tunes of operatic songs: evidence for independent processing. Percept. Psychophys. 63, 1201–1213 (2001).

Saffran, J.R., Aslin, R.N. & Newport, E.L. Statistical learning by 8-month old infants. Science 274, 1926–1928 (1996).

Saffran, J.R., Johnson, E.K., Aslin, R.N., & Newport, E.L. Statistical learning of tone sequences by human infants and adults. Cognition 70, 27–52 (1999).

Trehub, S.E., Trainor, L.J., & Unyk, A.M. Music and speech processing in the first year of life. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 24, 1–35 (1993).

Pantev, C., Roberts, L.E., Schulz, M., Engelien, A. & Ross B. Timbre-specific enhancement of auditory cortical representations in musicians. Neuroreport 12, 169–174 (2001).

Menning, H., Imaizumi, S., Zwitserlood, P. & Pantev, C. Plasticity of the human auditory cortex induced by discrimination learning of non-native, mora-timed contrasts of the Japanese language. Learn. Mem. 9, 253–267 (2002).

Zatorre, R., Evans, A.C., Meyer, E., & Gjedde, A. Lateralization of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science 256, 846–849 (1992).

Gandour, J. et al. A crosslinguistic PET study of tone perception. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, 207–222 (2000).

Schön, D., Magne, C. & Besson, M. The music of speech: electrophysiological study of pitch perception in language and music. Psychophysiology (in press).

Hickok, G. & Poeppel, D. Towards a functional neuroanatomy of speech perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 131–138 (2000).

Zatorre, R.J., Belin, P. & Penhune, V.B. Structure and function of auditory cortex: music and speech. Trends Cogn. Sci. 6, 37–46 (2002).

Wallace, W. Memory for music: Effect of melody on recall of text. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 20, 1471–1485 (1994).

Besson, M., Faïta, F., Peretz, I., Bonnel, A.-M. & Requin, J. Singing in the brain: independence of lyrics and tunes. Psychol. Sci. 9, 494–498 (1998).

Hébert, S. & Peretz, I. Are text and tune of familiar songs separable by brain damage? Brain Cogn. 46, 169–175 (2001).

Jakobson, L.S., Cuddy, L.L. & Kilgour, R. Time tagging: a key to musicians' superior memory. Music Percept. 20, 307–313 (2003).

Kolk, H.H. & Friederici, A.D. Strategy and impairment in sentence understanding by Broca's and Wernicke's aphasics. Cortex 21, 47–67 (1985).

Swaab, T.Y. et al. Understanding ambiguous words in sentence contexts: electrophysiological evidence for delayed contextual selection in Broca's aphasia. Neuropsychologia 36, 737–761 (1998).

Bharucha, J.J. & Stoeckig, K. Reaction time and musical expectancy. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 12, 403–410 (1986).

Bigand, E. & Pineau, M. Global context effects on musical expectancy. Percept. Psychophys. 59, 1098–1107 (1997).

Tillmann, B., Bigand, E. & Pineau, M. Effect of local and global contexts on harmonic expectancy. Music Percept. 16, 99–118 (1998).

Bigand, E., Madurell, F., Tillmann, B. & Pineau, M. Effect of global structure and temporal organization on chord processing. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 25, 184–197 (1999).

Tillmann, B. & Bigand, E. Global context effects in normal and scrambled musical sequences. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 27, 1185–1196 (2001).

Justus, T.C. & Bharucha, J.J. Modularity in musical processing: the automaticity of harmonic priming J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 27, 1000–1011 (2001).

Bharucha, J.J. & Stoeckig, K. Priming of chords: spreading activation or overlapping frequency spectra? Percept. Psychophys. 41, 519–524 (1987).

Tekman, H.G. & Bharucha, J.J. Implicit knowledge versus psychoacoustic similarity in priming of chords. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 24, 252–260 (1998).

Bigand, E., Poulin, B., Tillman, B., Madurell, F. & D'Adamo, D.A. Sensory versus cognitive components in harmonic priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 29, 159–171 (2003).

Haarmann, J.J. & Kolk, H.H.J. A computer model of the temporal course of agrammatic sentence understanding: the effects of variation in severity and sentence complexity. Cognit. Sci. 15, 49–87 (1991).

Blumstein, S.E., Milberg, W.P., Dworetzky, B., Rosen, A. & Gershberg, F. Syntactic priming effects in aphasia: an investigation of local syntactic dependencies. Brain Lang. 40, 393–421 (1991).

McNellis, M.G. & Blumstein, S.E. Self-organizing dynamics of lexical access in normals and aphasics. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 13, 151–170 (2001).

Blumstein, S.E. & Milberg, W. Language deficits in Broca's and Wernicke's aphasia: a singular impairment. in Language and the Brain: Representation and Processing. (eds. Grodzinsky, Y., Shapiro, L. & Swinney, D) 167–184 (Academic, New York, 2000).

Hsaio, F., & Gibson, E. Processing relative clauses in Chinese. Cognition (in press).

Krumhansl, C.L. The psychological representation of musical pitch in a tonal context. Cognit. Psychol. 11, 346–384 (1979).

Krumhansl, C.L., Bharucha, J.J. & Kessler, E.J. Perceived harmonic structure of chords in three related musical keys. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 8, 24–36 (1982).

Krumhansl, C.L. & Kessler, E.J. Tracing the dynamic changes in perceived tonal organization in a spatial map of musical keys. Psychol. Rev. 89, 334–368 (1982).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Neurosciences Research Foundation as part of its program on music and the brain at The Neurosciences Institute, where A.D.P. is the Esther J. Burnham fellow. I thank E. Bates, S. Brown, J. Burton, J. Elman, T. Gibson, T. Griffiths, P. Hagoort, T. Justus, C. Krumhansl, F. Lerdahl, J. McDermott and B. Tillmann.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Supplementary information

Supplementary Audio 1.

The syntax of harmonic structure in music A very important aspect of Western European tonal music (from approximately 1600 to 1900) is its harmonic structure, a system of norms involving the organization of tones, chords, and keys. For example, basic chords (simultaneous soundings of tones) are built from three pitches separated by musical thirds (e.g. "triads" such as C-E-G or D-F-A), with further principles for modifying triads with additional tones. Chord formation thus forms one level of syntactic patterning, concerned with the "vertical" organization of tones. Another level concerns the "horizontal" (sequential) patterning of tones and chords, which plays a vital role in defining keys or coherent tonal regions. (For those unfamiliar with the concept of a musical key, a brief description is given in the section of the paper titled "Syntactic processing in music: Tonal Pitch Space Theory"). For the purposes of this article, the essential point is that many of the norms of tonal syntax are implicitly learned by listeners who grow up listening to this music or to music based on similar conventions (a good deal of popular music of the past 100 years has been strongly influenced by these conventions) [cf. ref. 40 in the paper]. A brief illustration of sequential tonal syntax is provided by the following two sound examples from a recent study by Tillmann et al. [Tillmann, B., Janata, P., Birk, J., & Bharucha, JJ. The costs and benefits of tonal centers for chord processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 29, 470-482 (2003)]. This example illustrates a conventional chord progression in the style of J.S. Bach. For an example of music in which each individual chord is harmonically well-formed, but the sequence is syntactically odd because chords from different keys are combined, see Supplementary Audio 2. Like the study of linguistic syntax, the study of harmony has a large theoretical literature. For an introduction aimed at beginners, see Kostka, S. & Payne, D. Tonal Harmony, with an Introduction to Twentieth Century Music, 4th ed. (McGraw Hill, New York, 2000). (WAV 592 kb)

Supplementary Audio 2.

Each individual chord is harmonically well-formed, but the sequence is syntactically odd because chords from different keys are combined (see legend for Supplementary Audio 1 for further explanation). (WAV 513 kb)

Supplementary Audio 3.

Sour notes in music A "sour note" is a note which sounds odd because it violates musical key structure, i.e. it does not belong to the scale of the current musical key. It is not physically deviant in any way, and can sound perfectly normal in another context. The "sourness" of a sour note depends on enculturation in a particular musical tradition, and reflects implicit knowledge of tonal norms [cf. Janata, P., Birk, J.L., Tillmann, B., & Bharucha, J.J. Online detection of tonal pop-out in modulating contexts. Music Perception 20, 283-305 (2003)]. Sour notes in Western European tonal music are easily detected by people who have grown up with this music, both musicians and nonmusicians alike. In fact, the inability to detect sour notes is diagnostic of "congenital amusia" [cf. ref. 16 in the paper]. The following melody contains a sour note about 2/3 of the way through the sample. This melody is from the Essen folksong database (www.esac-data.org), where it is indexed as K0016 in the Kinder0 file (the melody does not have the sour note in its original version). For a recent discussion of the cognitive neuroscience of melody, see Patel, A.D. in The Cognitive Neuroscience of Music (eds. Peretz, I. & Zatorre, R.) (Oxford University Press, Oxford, in press). (WAV 2129 kb)

Supplementary Audio 4.

Christus, der ist mein Leben 1st phrase (J.S. Bach) (WAV 861 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, A. Language, music, syntax and the brain. Nat Neurosci 6, 674–681 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1082

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1082

This article is cited by

-

Subcortical responses to music and speech are alike while cortical responses diverge

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

The impact of sound stimulations during pregnancy on fetal learning: a systematic review

BMC Pediatrics (2023)

-

Temporal dynamics of statistical learning in children’s song contributes to phase entrainment and production of novel information in multiple cultures

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Regular rhythmic primes improve sentence repetition in children with developmental language disorder

npj Science of Learning (2023)

-

Lessons learned in animal acoustic cognition through comparisons with humans

Animal Cognition (2023)