Abstract

Paediatric adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare malignancy with poor prognosis. Here we analyse 37 adrenocortical tumours (ACTs) by whole-genome, whole-exome and/or transcriptome sequencing. Most cases (91%) show loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome 11p, with uniform selection against the maternal chromosome. IGF2 on chromosome 11p is overexpressed in 100% of the tumours. TP53 mutations and chromosome 17 LOH with selection against wild-type TP53 are observed in 28 ACTs (76%). Chromosomes 11p and 17 undergo copy-neutral LOH early during tumorigenesis, suggesting tumour-driver events. Additional genetic alterations include recurrent somatic mutations in ATRX and CTNNB1 and integration of human herpesvirus-6 in chromosome 11p. A dismal outcome is predicted by concomitant TP53 and ATRX mutations and associated genomic abnormalities, including massive structural variations and frequent background mutations. Collectively, these findings demonstrate the nature, timing and potential prognostic significance of key genetic alterations in paediatric ACT and outline a hypothetical model of paediatric adrenocortical tumorigenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adrenocortical tumours (ACTs) are rare1. A good outcome, as with most paediatric embryonal tumours, requires early diagnosis and complete surgical resection. Children with locally advanced or metastatic disease have a very poor prognosis, even with surgery and intensive chemotherapy2.

Childhood ACT is often associated with germline TP53 mutations (Li-Fraumeni syndrome)3 or constitutional genetic and/or epigenetic alterations affecting chromosome 11p15 (Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, BWS)4. Both Li-Fraumeni syndrome and BWS have highly variable phenotypes, which include susceptibility to ACT and other embryonal malignancies5. The factors contributing to sporadic paediatric ACTs are unknown, although the similarity of these cases to those with a constitutional predisposition suggests a common mechanism of tumorigenesis1.

ACT is uniquely amenable to molecular studies relevant to paediatric embryonal neoplasms in general. First, the marked clinical endocrine manifestations of ACT (for example, virilization and Cushing syndrome) allow access to tumour tissue at an early disease stage. Second, ACT shares the epidemiological and molecular features of embryonal tumours5. Finally, a cluster of ACTs arising from a founder TP53 mutation (R337H) in southern Brazil allows biologic, prognostic and therapeutic studies in a relatively large group of cases with a common predisposing factor6,7,8,9.

Staging of paediatric ACT is based on tumour size and evidence of residual tumour after surgery1. Histopathologic classification criteria, which have been invaluable in distinguishing adenoma (benign) from carcinoma (malignant) in adult ACTs10, have a limited role in guiding therapeutic decisions in paediatric ACTs, the great majority of which are classified as carcinomas or histology of undetermined malignant potential11,12. To advance our understanding of the initiation and progression of paediatric ACT, we undertook a comprehensive genomic analysis of 37 representative cases, including 12 tumours associated with the germline TP53-R337H mutation, using a combination of whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES) and transcriptome profiling (RNA-seq).

Results

Clinical data

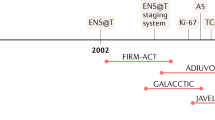

The clinical and biological characteristics of the 37 newly diagnosed ACT cases studied by WGS and WES are summarized in Supplementary Table 1a,b. The median age of the 25 girls and 12 boys at diagnosis was 53.5 months (range, 9.7–184.7 months). Tumours were sporadic (n=10) or associated with constitutional cancer predisposition conditions (Brazilian founder TP53-R337H (n=12); other types of germline TP53 mutations (n=13) and BWS (n=2)) and included 29 carcinomas, 3 adenomas and 5 tumours of undetermined malignant potential. These cases were selected on the basis of availability of paired tumor and germline samples and isolation of high-quality tumour DNA. Although treatment was not uniform, it generally adhered to the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) ARAR0332 protocol1, consisting of surgery alone for stage I and II disease, and surgery followed by intensive chemotherapy (cisplatin, doxorubicin, etoposide and mitotane) for advanced-stage (III and IV) disease. At a median follow-up of 38 months, 11 of 35 (31%) patients had experienced an adverse event (relapse or death). Five of these eleven had died of progressive disease at the time of this report, and six remained alive in second complete remission. Two patients were lost to follow-up. Clinical data from 34 additional ACT patients studied as an independent comparison group (‘convenience cohort’) is included in Supplementary Table 1c.

Genome and transcriptome analyses

Primary ACTs and matched peripheral blood DNA were analysed by WGS (n=19) at an average 41.9X coverage (Supplementary Table 2a) or by WES (n=18) at an average 84.8X coverage (Supplementary Table 2b; Pediatric Cancer Genome Project, http://pcgpexplore.org/). All genetic lesions, including single-nucleotide variations (SNV), small insertions/deletions (indels) and structural variations (SVs), were experimentally validated (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the WGS samples, the median number of nonsilent point mutations was 5 (range, 1–97), the median background mutation rate (BMR) was 3.78 × 10−7 (range, 5.01 × 10−8–2.40 × 10−6) and the median number of SVs per case was 61 (range, 0–812; Supplementary Table 3a–d). Transcriptome profiles of normal adrenocortical tissue (n=6) and ACT samples from the WGS cohort (n=16) were analysed using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq; Supplementary Table 2c).

TP53 mutations

Germline TP53 mutations were present in 25 of the 37 patients (68%) in the combined WGS and WES cohorts, 12 of which were the Brazilian founder R337H mutation (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Somatic mutations (R175H, R273C and a homozygous deletion of ~200 kb of chromosome 17 encompassing TP53) were also identified in 3 of the 12 ACTs associated with wild-type germline TP53 (Supplementary Fig. 3a,b).

(a) Upper panel: clinicopathological features of 19 patients in the WGS cohort. Centre panel: genetic alterations, including mutational status of TP53 (R337H identified by asterisk), ATRX and CTNNB1; telomere length; number of SVs; BMR; chromothripsis and kataegis. Und: undetermined malignancy. Lower panel: RNA expression of selected genes involved in chromosomal segregation and cell cycle control. Three distinct tumour groups (labelled below) emerged from this analysis. Control: normal adrenocortical tissue. (b) Kaplan–Meier probability of event-free survival (exact log-rank test) of paediatric ACT patients in group 1 versus others.

Sanger sequencing identified germline TP53 mutations in 11 of the 34 cases (32%) in the independent comparison cohort (Supplementary Table 1c). Of the 23 ACTs in this group associated with germline wild-type TP53, three tumours acquired a TP53 mutation (c.134_135 insT, E180K and R273H; Supplementary Fig. 4a).

Somatic ATRX mutations

ATRX encodes a helicase that functions in chromatin remodelling and telomere structural maintenance, and it cooperates with DAXX to incorporate the histone variant H3.3 into chromatin13. ATRX somatic nonsense mutations and SVs deleting multiple exons were identified by WGS in 6 of the 19 ACTs (32%), all of which were associated with germline TP53 mutations (Fig. 1a and 2a,b). An ATRX somatic missense mutation (R2164S) was also identified by WES in the case with somatic homozygous deletion of TP53 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3b). No mutations were detected in the coding region of DAXX or TERT by WGS or WES. Furthermore, no mutations were identified in the TERT core promoter by targeted Sanger sequencing. Although broad regional amplification encompassing the TERT locus was observed in 13 of the 19 WGS cases (68%), no TERT expression was detected with RNA-seq.

(a) Distribution of nonsilent single-nucleotide variations in ATRX (blue dots: nonsense mutations; red dot: missense mutation). (b) Wiggle plots showing internal deletion of multiple exons in the ATRX gene in SJACT005, SJACT062 and SJACT069 (diagnostic tumour [D] and germline [G] samples). (c) Relative telomere length determined by WGS in paediatric ACTs versus matched germline samples. (d) Images of tumour samples hybridized with the telomeric FISH (red) and chromosome 4p (green) probes and stained with DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). High-magnification views show the large, ultrabright signal in ATRX-mutant adrenocortical tumour cells (SJACT007). Scale bars, 1 μm.

WGS-based telomere length analysis showed an increase in telomeric DNA in all six tumours with ATRX mutations, but not in tumours with wild-type ATRX (P=3.7 × 10−5, Fisher’s exact test; Fig. 2c). Telomere fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of 22 available formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumour specimens revealed large, ultrabright telomere foci (Fig. 2d) in cases harbouring ATRX mutations (n=5), suggesting the activation of an alternative lengthening of telomere mechanism. Telomere foci were also observed in the SJACT023 tumour, although WES did not detect an ATRX mutation.

Somatic β-catenin mutations

Somatic β-catenin (CTNNB1) mutations were identified in 3 of the 37 (8%) tumours analysed in the combined WGS and WES cohorts (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 5). Targeted Sanger sequencing of CTNNB1 exon 3 revealed 10 additional somatic mutations in 34 paediatric ACTs in the independent comparison cohort (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Overall, CTNNB1 mutations (n=13) were detected only in tumours with wild-type germline TP53 (n=35) and not in those with constitutional TP53 mutations (n=36; P=2.5 × 10−5, Fisher’s exact test). However, three tumours with somatic CTNNB1 mutations had also acquired a TP53 mutation (IPACTR001, IPACTR013 and IPACTR019; Supplementary Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1c).

Genomic classification of ACT

WGS defined three groups of paediatric ACT based on the mutational status of TP53 and ATRX: Group 1 germline TP53 and somatic ATRX mutations (n=6); Group 2 germline TP53 mutations and no ATRX mutation (n=9); and Group 3 both wild-type TP53 and ATRX (n=4; Fig. 1a). Group 1 cases had significantly greater tumour weight (P=0.007, Mann–Whitney test), were significantly more likely to have stage 3 or 4 disease (P=0.020, Kendall test) and had poorer event-free survival than Groups 2 and 3 (P=5.0 × 10−5, exact log-rank test; Fig. 1a,b). Group 1 ACTs also had a significantly larger number of SVs (P=0.021, Mann–Whitney test) and higher BMR (P=0.015, Mann–Whitney test; Supplementary Fig. 3c). In addition, these tumours showed significantly higher expression of genes associated with chromosome instability and deregulation of cell cycle control (PTTG1, P=0.019; ESPL1, P=0.015; CCNB1, P=0.018; BUB1, P=0.023; TPX2, P=0.032; and MCM2, P=0.040, t-test; Fig. 1a). Although all cases in Group 2 carried germline TP53 mutations (eight of nine cases had the founder R337H mutation and were diagnosed in southern Brazil), they displayed variable clinical findings. Group 2 patients with the R337H mutation were young (median age, 30 months), exhibited signs of virilization and had relatively small tumours (median tumour weight 68 versus 585 g in Group 1 (P<0.006, Wilcoxon rank sum test)). These tumours showed variable numbers of SVs and BMR, and variable expression of selected target genes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3c). A distinguishing feature of this group is the lack of ATRX mutations and the shortening of telomeres as compared with Group 1. Group 3 tumours showed a relatively small number of SVs and a low BMR, and gene expression of those selected genes was similar to that in normal adrenocortical tissue, consistent with their more favourable outcome (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3c).

WGS did not reveal any specific genetic alterations that distinguished ACTs harbouring the founder TP53-R337H from tumours with other TP53 mutations. However, R337H tumours that had acquired an ATRX mutation (cases SJACT062 and SJACT069) clustered in Group 1 and exhibited an aggressive phenotype (Figs 1 and 3). The remaining eight R337H cases showed variable molecular profiles and disease stage (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Figure 3 illustrates the relationship among histopathological features, tumour weight, stage and complexity of genomic abnormalities for four cases with the same predisposing TP53-R337H germline mutation.

All tumours had a high mitotic rate (>5 per 50 high-power fields, H&E, × 400). Histology showed a vague nested and trabecular pattern with occasional unpatterned cellular sheets of variable size. Three cases (SJACT063, SJACT062 and SJACT069) had a high nuclear grade and marked cellular pleomorphism. SJACT070 showed occasional enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei with one or more prominent nucleoli. Necrotic cells and atypical mitotic figures (arrow) are identified in SJACT63 and SJACT69. Accumulation of genomic alterations illustrated by the Circos plots (bottom panels) paralleled an increase in tumour weight and correlated with a more aggressive tumour phenotype (Group 1 versus Group 2). Note: labels for gene-disrupting SVs (SJACT063 and SJACT062) and noncoding mutations (SJACT069) were removed from the Circos plots.

Loss of heterozygosity of chromosomes 11 and 17

Chromosome 17 loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was observed in 28 of the 37 ACTs (76%) by WGS and WES. All tumours with germline (n=25) and somatic (n=3) TP53 mutations underwent LOH with selection against the wild-type allele (Supplementary Fig. 2). More specifically, WGS demonstrated copy-neutral LOH (cn-LOH) of the entire chromosome 17 in all tumours associated with germline TP53 mutations (n=15), as well as in two (SJACT003 and SJATC004) of the four cases with wild-type TP53 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Chromosome 11p LOH was also identified in 32 of the 35 ACTs (91%). Two BWS patients (SJACT009 and SJACT065) with germline 11p homozygosity, indicative of uniparental disomy, were excluded from the analysis as LOH could not be assessed (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Fig. 4a). Furthermore, cn-LOH of chromosome 11p was demonstrated by WGS in 14 of the 18 informative ACTs (Supplementary Fig. 2). Microsatellite marker analysis of an additional 22 paediatric ACT cases from our independent comparison cohort revealed chromosome 11p LOH in 20 tumours (95%, as IPACTR004 was excluded due to uniparental disomy; Supplementary Fig. 4c). Remarkably, 100% of the cases from the combined cohorts that underwent chromosome 11p15 LOH and had available parental DNA (n=23) selectively retained the paternal chromosome (P=2.4 × 10−7, sign test; Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4c).

(a) Microsatellite analysis of chromosome 11p15 in the WES cohort. All cases with available parental DNA demonstrated selective loss of maternal chromosome 11p15 (n=8, purple). (b) Temporal order of chromosome 11p and 17p cn-LOH and accumulation of SNVs in SJACT002. Scatter plots show MAFs of somatic SNVs and their genomic positions (individual dots) combined with two-dimensional (2D) density plots of AI values of germline heterozygous SNPs in cn-LOH regions of chromosomes 11p (left) and 17p (centre). At right, AI values in cn-LOH regions of chromosomes 11p and 17p were compared with the MAF distribution of somatic SNVs in genome-wide cn-LOH regions. (c) A three-dimensional (3D) scatter plot summarizes the temporal order of cn-LOH of chromosomes 11p and 17p and somatic SNV accumulation in paediatric ACTs. Shown are the median AI values for the chromosome 11p cn-LOH region, the median AI values for the chromosome 17p cn-LOH region and the median MAF of SNVs in genome-wide cn-LOH regions of 14 cases; SJACT002 and SJACT005 are labelled. See also Supplementary Fig. 7b.

Human chromosome 11p15 contains a large cluster of imprinted genes, including IGF2, CDKN1C, KCNQ1 and H19. IGF2 is a paternally expressed fetal growth factor, whereas the cell cycle inhibitor CDKN1C (p57), potassium channel protein KCNQ1 and the noncoding H19 transcripts are expressed from the maternal allele. Expression of genes localized at 11p15 (chr11:1704500–3658789) was analysed with transcriptome profiling. RNA-seq confirmed greater expression of IGF2 in all tumours in the WGS cohort compared with normal adrenocortical tissue (P=2.987 × 10−7, t-test; Supplementary Fig. 6). Expression of KCNQ1, CDKN1C and H19 was low in most cases, consistent with loss of the maternal chromosome 11p. SJACT006, which retained both parental copies of chromosome 11, also displayed elevated IGF2 expression and deregulation of maternally expressed genes, suggesting a loss of imprinting control at this locus (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Timing of cn-LOH of chromosomes 11 and 17

To infer the temporal order of somatic SNV acquisition and cn-LOH in chromosomes 11 and 17, we compared the mutant allele fractions (MAFs) of SNVs in cn-LOH regions to allelic imbalance (AI) values, which express the different MAFs (germline heterozygous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)) in tumour versus germline samples (Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Fig. 7). A cn-LOH event in the tumour cells will lead to an expected AI value of 0.5. Similarly, somatic SNVs acquired before cn-LOH would result in either a homozygous reference allele (R) or a homozygous mutant (M) allele, while SNVs accumulated after cn-LOH would remain heterozygous in the absence of a second hit (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Our analysis of 14 informative WGS samples demonstrated that most SNVs in chromosomes 11p and 17p were acquired after cn-LOH, although SJACT005 underwent cn-LOH during SNV accumulation (Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Fig. 7b). These findings indicate that cn-LOH of chromosomes 11p and 17p occurs early in adrenocortical tumorigenesis and precedes the accumulation of SNVs in these regions.

Chromosomal integration of human herpesvirus-6

Human herpesvirus-6 (HHV6) was detected by WGS in the germline and tumour DNA of SJACT004 (Fig. 5a) and by Sanger sequencing in SJACT017. FISH analysis confirmed the site of chromosomal integration of HHV6 as the telomeric region of 11p in both cases (Fig. 5b). PCR analysis demonstrated paternal transmission of chromosomally integrated HHV6 in SJACT017 (Fig. 5c). Microsatellite marker analysis and WGS confirmed chromosome 11 LOH with retention of integrated HHV6 in both cases (Supplementary Figs 2 and 4c and Fig. 4a). Genomic and transcriptome analyses of SJACT004 identified few somatic SNVs and SVs, but showed elevated IGF2 expression (Supplementary Figs 2 and 6). Both ACTs were small, stage 1 tumours and with good prognosis (Supplementary Table 1a,b).

(a) Coverage plot for cases SJACT004 and SJACT005 showing diagnostic tumour (D) and germline (G) samples reveals integration of the full-length HHV6 genome in SJACT004. The HHV6 genome is duplicated in the tumour sample as a consequence of cn-LOH. (b) FISH of metaphase chromosomes from peripheral blood confirmed HHV6 integration at 11p in both cases. The MLL probe (chromosome 11q23) was used as control (left, SJACT004; right, SJACT017). (c) HHV6 MCP (major capsid protein) and U94 were amplified with PCR from SJACT017 (germline and tumour) and parental DNA demonstrating paternal vertical transmission of integrated HHV6. Exon 6 of the TP53 gene was amplified as DNA quality control.

Other genetic events

Chromosomal copy number alterations (CNAs) were also assessed by a modified version of GISTIC (genomic identification of significant targets in cancer). Deletion of chromosome 4q34 was observed in 11 of the 19 tumours (58%; Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). The most commonly deleted region overlapped a 5-Mb area encompassing LINC00290 (long intergenic nonprotein-coding RNA 290)14.

Chromosomal copy number gains were widespread, with 9q being over-represented and amplified in 16 of the 19 WGS ACTs, similar to previously reported findings (Supplementary Fig. 8a,c)14. Chromosome shattering consistent with chromothripsis15 (Supplementary Fig. 9) and patterns of localized hypermutation (kataegis16; Supplementary Fig. 10) were observed in late-stage tumours (Fig. 1a). Structural variants resulting in the expression of fusion genes were infrequent and nonrecurrent (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

Our genomic findings define cn-LOH of chromosome 11p, with selection against the maternal chromosome and consequent IGF2 overexpression, as an early event and a hallmark of paediatric adrenocortical tumorigenesis.

Although paediatric ACT is strongly associated with germline TP53 mutations17,18,19 (60–70% of children with ACT3), only 4–6% of carriers develop ACTs1, suggesting the involvement of cooperating genetic alterations. We propose that germline TP53 mutations may contribute to adrenocortical tumorigenesis by promoting chromosomal instability20,21. In this setting, aneuploid adrenocortical cells that experience chromosome 11p LOH and deregulation of imprinted genes on 11p15 may be selected and expanded via constitutive overexpression of IGF2, which encodes a potent mitogen and fetal growth-promoting protein22,23. This mechanism is consistent with chromosome 11p abnormalities and IGF2 overexpression in all cases of ACT with germline TP53 mutations. Clones that undergo chromosome 17 LOH and lose wild-type TP53 become more unstable, accumulate additional SNVs and are selected for further expansion. In support of this hypothesis, our temporal studies place cn-LOH of chromosomes 11p and 17 during early tumorigenesis, before the acquisition of widespread genomic alterations.

Our WGS study included 10 Brazilian cases with the founder TP53-R337H mutation, which could influence the resulting genomic landscape findings. TP53-R337H is a missense mutation that is partially functional6,24; hence, we expected that genomic changes could be different from those with nonfunctional mutations. Our genomic studies showed that some cases with the R337H mutation had secondary genetic events that were similar to those seen with other types of TP53 mutations, such as concomitant cn-LOH of chromosomes 11 and 17p early during tumorigenesis, as well as the deregulation of IGF2 expression and acquired ATRX mutations. These findings are consistent with those from high-density SNP analysis that demonstrated that the pattern of gains and losses is similar in paediatric ACTs with R337H and other TP53 mutations14. However, other cases with R337H mutations had much simpler genomes similar to those with wild-type TP53. It is possible that secondary genomic changes increase with time from tumour initiation to diagnosis. Alternatively, other genetic constitutional or acquired changes account for the observed heterogeneity observed in cases with the R337H mutations. Further studies will be required to examine these possibilities.

LOH of chromosome 11p15 and genomic imprinting abnormalities within this region that lead to constitutive IGF2 expression are features of many other paediatric tumours, including rhabdomyosarcoma25, Wilms tumour26 and hepatoblastoma27. Similarly, adult adrenocortical carcinomas, but not adenomas, show genomic imprinting abnormalities at chromosome 11p15 (refs 28, 29). However, transgenic mouse models demonstrate that IGF2 overexpression is not by itself sufficient to promote adrenocortical tumorigenesis30 but must cooperate with other genetic alterations, such as activation of β-catenin31. Consistent with these findings, CTNNB1-activating mutations were relatively frequent in our cohort, particularly in cases with germline wild-type TP53.

Assié et al.29 recently reported the characterization of 45 adult adrenocortical carcinomas (ACCs) using an integrated genomic analysis approach. A comparison of our findings to this published study highlights similarities and differences in the genetic changes that occur in paediatric and adult ACTs (Supplementary Table 5). Remarkably, 11p15 LOH involving the IGF2 locus was observed in both paediatric ACT (91%) and adult ACC (82%), underscoring the critical role of deregulated IGF2 expression in adrenal cortex tumorigenesis. Aneuploidy with widespread chromosomal gains (for example, chromosome 19) and deletions (for example, 4q34.3) was also observed in both paediatric and adult cases. However, amplification of chromosome 9q, a region that includes NOTCH1 and NR5A1 (Steroidogenic Factor-1), occurred in 90% of paediatric ACTs (Supplementary Fig. 8a,c), but not in adult ACC29. Activating mutations in CTNNB1 were common to both paediatric and adult ACT, but additional mutations within the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway, in particular ZNRF3, were only observed in adult tumours. Germline TP53 mutations were predominantly associated with paediatric ACT, whereas somatic TP53 mutations were relatively infrequent in both groups. The alternative lengthening of telomere phenotype was associated with DAXX or ATRX mutations in adult tumours, but exclusively with ATRX mutations in paediatric cases. Amplification of TERT was common in both groups, but no TERT mutations were detected in the paediatric cases, consistent with the absence of TERT expression.

A lack of strong prognostic indicators has limited progress in the management of childhood ACT. Overall event-free survival is only ~50%, and patients with advanced-stage disease have very poor overall survival1,2. Unlike studies of other paediatric embryonal tumours32,33,34, histopathological examination11 and molecular findings35 in paediatric ACT has not produced relevant prognostic categories or novel treatment approaches. Tumour weight, volume and surgical resectability form the basis of the current COG disease-stage classification1. However, this system needs improvement, as many patients experience relapse despite small, completely excised tumours, while others are cured despite histological findings suggestive of carcinoma36.

Our genomic analysis opens opportunities to improve the current tumour size-histology-disease stage prognostic scheme for paediatric ACT1,2. Notably, tumours with both germline TP53 and somatic ATRX mutations (Group 1) were significantly associated with high tumour weight, advanced disease (COG stage III/IV) and poor event-free survival. SJACT069 (R337H) exemplifies such a case; it was staged as limited disease (COG stage II) and initially managed with surgery alone, but later metastasized to the lungs. Moreover, five of six patients in Group 1 had adverse events (relapse or death), consistent with the genomic findings indicative of an aggressive phenotype. Cases with germline TP53 mutations and wild-type ATRX (Group 2) are clinically and molecularly heterogeneous. Although all cases in this group carried TP53 mutations (eight of the nine cases harbour the founder R337H), they had fewer genomic abnormalities, smaller tumours and generally much better clinical outcome than cases in Group 1. It is not surprising that patients in southern Brazil with the R337H mutation were diagnosed earlier, as paediatricians of that region are familiar with the first signs of ACT and promptly refer these children for treatment. However, three patients (one with the TP53 G245C and two with the Brazilian R337H mutation) overexpressed genes associated with chromosome instability and cell cycle control (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Table 1). The two cases with R337H required chemotherapy because of advanced-stage disease in one and tumour rupture in the other. The patient with the G245C, a child more than 10 years of age at diagnosis of ACT, had delayed diagnosis of a very large tumour in the absence of endocrine signs (a ‘nonfunctional’ tumour). This child was treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy, but eventually died of relapsed disease. These observations suggest that paediatric TP53-associated tumours arise from a simpler genomic background (adenoma or undetermined malignant potential) and progress to acquire complex and unstable genomic aberrations (carcinoma). The results of newborn screening for the TP53 mutation in Brazil and surveillance of carriers for early signs of ACT9 are consistent with this concept37. Finally, ACTs with wild-type TP53 exhibit relatively simple genomes and, despite their large size in some cases, patients generally have a good outcome. Because of the small number of these cases, additional genomic studies will be needed to clarify the role of molecular changes in this subset of patients.

In two of our cases (SJACT004 and SJACT017), HHV6 was selectively integrated into the telomeric region of chromosome 11p. HHV6 is known to integrate into the genome at a low frequency (~1%), preferring the telomeric regions of chromosomes 9q, 11p, 17p and 19q (refs 38, 39). A recent report documented the role of integrated HHV6 in disrupting telomeres, leading to selective aneuploidy40. Whether chromosomal integration of HHV6 facilitates 11p cn-LOH and deregulation of imprinting at the 11p15 locus, leading to IGF2 overexpression, remains to be determined.

In summary, our study identified key genetic alterations and their temporal relationships in paediatric adrenocortical tumorigenesis. The genomic complexity of childhood ACTs, particularly those with both germline TP53 and acquired ATRX mutations, may explain the failure of standard chemotherapy, underscoring the importance of early diagnosis and improved prognostic classification.

Methods

Patients and samples

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians for inclusion in the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St Jude) International Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumor Registry (IPACTR; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00700414) or for participation in COG ARAR0332 protocol (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00304070). IPACTR registers childhood cases of ACT worldwide. COG studies enroll patients from the United States, Canada and southern Brazil, where 90% of cases carry the founder TP53-R337H mutation. Diagnosis was made on the basis of the gross and histologic appearance of tissue obtained at surgery. The diagnosis of ACT was centrally reviewed and confirmed. Tumours were further classified as adenoma (benign), carcinoma (malignant) or having histology of undetermined malignant potential. No attempt was made to obtain individual tumour scores.

Samples for WGS (n=19) and WES (n=18) included matched peripheral blood and primary tumour tissue from 26 IPACTR patients and 11 COG patients. An additional group of 34 IPACTR patients with matched primary tumour and blood samples, and blood-derived DNA from 23 sets of parents, were included for analysis of chromosome 11p LOH, TP53 and CTNNB1 mutation. Six samples of normal adrenocortical tissue obtained during nephrectomy for Wilms tumour were used as controls in gene expression studies as well 16 tumour samples studied in the WGS cohort. All tumour samples underwent estimation of the purity-adjusted MAF, tumour purity and tumour heterogeneity and quantitative analysis of chromothripsis41. This study was approved by the St Jude Institutional Review Board and by the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program of the National Cancer Institute (ARAR12B1).

Tumour purity estimations

For germline heterogeneous SNPs, LOH measures the absolute difference between the MAF in tumour and that in germline sample (0.5). LOH is the result of copy number alterations and/or cn-LOH in tumour cells. Compared with copy number gains (a single copy gain in 100% tumour results in a LOH value of 0.167), regions with copy number loss showed stronger LOH (a single copy loss in 100% tumour result in a LOH value of 0.5). Consequently, we used LOH signals in copy neutral or heterozygous copy number loss regions (CNA value between [−1, 0]) to estimate tumour purity for all WGS samples. Briefly, a single copy loss in x% tumour cells resulted in an estimated CNA value of  and a LOH value of

and a LOH value of  . Assuming that the remaining LOH signal came from cn-LOH (cn-LOH in x% tumour cell resulted in a LOH value of

. Assuming that the remaining LOH signal came from cn-LOH (cn-LOH in x% tumour cell resulted in a LOH value of  ), the tumour content in a region could be estimated as the sum of the fraction with copy number loss and the fraction with cn-LOH by:

), the tumour content in a region could be estimated as the sum of the fraction with copy number loss and the fraction with cn-LOH by:  . Using tumour content estimates from various regions within the genome, we performed an unsupervised clustering analysis using the mclust package (version 3.4.8) in R (version 2.11.1). The tumour purity of the sample was defined as the highest cluster centre value among all clusters.

. Using tumour content estimates from various regions within the genome, we performed an unsupervised clustering analysis using the mclust package (version 3.4.8) in R (version 2.11.1). The tumour purity of the sample was defined as the highest cluster centre value among all clusters.

Purity-adjusted MAF estimation

MAF for validated SNVs was estimated as  using deep sequencing data.

using deep sequencing data.

Tumour heterogeneity estimation

We used all validated autosomal SNVs satisfying the following criteria in heterogeneity analysis:

-

1

In copy neutral region (Log2ration between (−0.1, 0.1) in CNV analysis).

-

2

Not in regions with LOH (LOH value <0.1).

-

3

With MAF >0.05 or mutant allele count >2.

We drew the kernel density estimate plot for MAFs of the qualifying SNVs using the density function in the stat package in R. We also estimated the number of significant peaks and the relative MAF component for each peak (peaks with less than five SNVs, peaks with less than 1% SNVs and peaks with excessive variance were ignored). A sample with heterogeneity shows density peaks at a MAF smaller than 0.5 (the expected MAF assuming heterogeneous SNVs).

Kataegis analysis

Kataegis analysis was performed on all validated Tier1–3 SNVs and SV breakpoints for each sample. The intermutation distance for a SNV was calculated as the distance to its nearest neighbour. For each SNV, its distance to the nearest validated SV breakpoint was also calculated. We defined microclusters of kataegis as clusters that contain at least five consecutive SNVs with intervariant distance less than 10 kb. Mutant allele frequency (MAF) was estimated for SNVs with at least 20 × coverage in tumour BAMs based on deep sequencing of custom capture validation.

Whole-genome sequencing

WGS was performed as previously described42,43. WGS mapping, coverage, quality assessment, SNV, indel detection, tier annotation for SNVs, prediction of deleterious effects of missense mutations and identification of LOH have been described previously42. SVs were analysed by using the CREST software and were being annotated as previously described42,44. The reference human genome assembly NCBI Build 37 was used for mapping samples. CNAs were identified by comparing read depth in tumour versus matched normal samples and using a novel algorithm, CONSERTING (COpy Number SEgmentation by Regression Tree In Next-Gen sequencing).

SNVs were classified according to the following three tiers, as previously described42.

Tier1: Coding synonymous, nonsynonymous and splice-site variants and noncoding RNA variants.

Tier 2: Conserved variants (cutoff conservation score ≥500, based on either the phastConsElements28way table or the phastConsElements17way table from the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and variants in regulatory regions annotated by UCSC annotation (regulatory annotations included targetScanS, ORegAnno, tfbsConsSites, vistaEnhancers,eponine, firstEF, L1 TAF1 Valid, Poly(A), switchDbTss, encodeUViennaRnaz, laminB1 and cpgIslandExt)).

Tier 3: Variants in nonrepeat masked regions.

Tier 4: All other SNVs.

Exome sequencing

For exome sequencing, DNA libraries were prepared from 1 μg of WGA DNA from matched samples by using the Illumina TruSeq DNA library prep kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of library construction was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Germline and diagnostic library samples were independently pooled for exome capture by using the Illumina TruSeq Exome Enrichment kit as instructed by the manufacturer. Captured libraries were then clustered on the Illumina c-bot and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform by conducting 100 base pair-end-multiplexed reads at an equivalent of three samples per lane.

Sequence validation

To enrich regions containing putative sequence alterations, genomic coordinates of the WGS targets were used to order Nimbelgen Seqcap EZ solution bait sets (Roche). Library construction and target enrichment were performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions, using repli-G (Qiagen) WGA DNA. Enriched targets were sequenced on the Illumina platform by paired-end 100-cycle sequencing. The resulting data were converted to FASTQ files by using the CASAVA 1.8.2 (Illumina) programme and were mapped with a Burrows-Wheeler Aligner before pipeline analysis. Putative SNVs and indels from exon sequencing were validated by next-generation amplicon sequencing. Briefly, primers were designed for genomic regions (hg19) flanking the detected SNV but no nearer than 100 base pairs. PCR was performed by using 20–30 ng of WGA DNA from each sample. DNA from diagnostic tumour samples and matched germline samples was used for each primer set to confirm the presence of the SNV/indel in the diagnostic sample. Standard PCR was performed in 25-μl reactions, using Accuprime GC-rich DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with the following reaction conditions: 95 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min; and a 72 °C for 10 min extension with cooling to 4 °C. All PCR amplicons were verified on a 2% E-gel (Invitrogen) to ensure single amplified product.

Transcriptome sequencing

For library construction, 2–5 μg of total RNA was extracted from tumour samples by using Qiagen RNeasy Mini kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration was measured by using a NanoDrop 100 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). RNA integrity was measured by using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer Lab-on-a-chip system. Total RNA was treated with DNAse I (Invitrogen) and enriched for poly A-containing mRNA using oligo dT beads (Dynabeads, Invitrogen). The cDNA synthesis used random hexamers and the Superscript Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Paired-end reads from mRNA-seq were aligned to the following four database files by using a Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (0.5.5; (ref. 45: (i) human NCBI Build 37 reference sequence, (ii) RefSeq, (iii) a sequence file representing all possible combinations of nonsequential pairs in RefSeq exons and (iv) AceView database flat file downloaded from UCSC, representing transcripts constructed from human expressed sequence tag (EST). The mapping results from databases (ii)–(iv) were aligned to human reference genome coordinates. The final BAM file (compressed binary version of the Sequence Alignment/Map format) file was constructed by selecting the best alignment in the four databases. The RNA expression level was measured by fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped46. SVs were detected by using the CIRCERO algorithm, a novel algorithm that uses de novo assembly to identify SV in RNA-seq data (unpublished data). The structural variants detected in RNA-seq data were validated with MiSeq sequencing. Primer pairs were designed (with Primer3) to bracket the genomic regions containing putative SVs. The SVs found by RNA-seq are reported in Supplementary Table 4.

GISTIC analysis

We used cghMCR (an R implementation of a modified version of the GISTIC analysis47) to find regions that contained copy number alterations. We identified significantly amplified genes as those with segments of gain or loss (SGOL) scores 3 s.d.’s above the mean SGOL scores of all ‘gains’. Genes with SGOL scores 3 s.d.’s below the mean SGOL scores of all ‘losses’ were selected as significantly deleted genes.

Timing of cn-LOH

The cn-LOH regions were estimated from the CNA and LOH analysis data. When cn-LOH was identified in a pure tumour cell population, heterozygous alleles had become homozygous for either the reference allele or the alternative allele. Consequently, the MAF for SNVs accumulating before cn-LOH was either 0 (homozygous reference allele) or 1 (homozygous alternative allele), while SNVs occurring after cn-LOH had a maximum MAF of 0.5 (assuming no second mutation at the same locus) in tumour cells. We inferred the temporal order of cn-LOH and SNV accumulation in a genomic segment by comparing the AI values with the region’s MAF.

Telomeric DNA content and telomere FISH

The WGS data were analysed for total telomeric DNA content in tumours and matched germline DNA in 19 cases. Telomeric content reads containing (TTAGGG)4 or (CCCTAA)4 were counted and normalized to the average genomic coverage, and the log2 ratio of diagnostic and germline telomeric content estimates was then calculated to allow classification of telomeric content as gain, no change or loss48. Telomere FISH was performed on available formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples (n=22) from the WGS and WES cohorts. Interphase FISH was performed on 4-μm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. The Cy3-labelled TelG probe (PNAbio) was co-denatured with the target cells on a hotplate at 90 °C for 12 min. The slides were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C and then washed in 4 M urea/2 × SSC at 45 °C for 5 min. Nuclei were counterstained with 200 ng ml−1 of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories). The telomeric probe (red) hybridizes to telomeres on all chromosomes; a probe for 4p (green) was used as control.

Analysis of microsatellite markers on chromosome 11p

To identify commonly deleted regions on chromosome 11p15, we assessed LOH in 16 paired normal and tumour DNAs selected from the recurrence groups (WES) and in 22 additional IPACTR cases. We included peripheral blood DNA from 23 pairs of parents. Genomic DNA was extracted by using standard protocols. Fluorescence PCR semi-automated genotyping was used to detect and analyse allelic losses by using a panel of five microsatellite markers (D11S1363, D11S922, D11S4046, HUMTH01 and D11S988).

TP53 and CTNNB1 mutations

To detect and validate TP53 and CTNNB1 mutations, genomic DNA from ACT samples was tested by PCR-based bidirectional DNA sequencing of exons 2–11 and intron–exon boundaries for TP53 and exon 3 (codons 5–70) for CTNNB1. Sequencing reactions were carried out on a high-throughput 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

TERT core promoter mutational status

The TERT core promoter (HG19 coordinates, chr5: 1295151–1295347) was amplified in 19 paediatric ACT using PCR. Briefly, 10–20 ng of sample DNA was added to a 25-μl reaction containing amplitaq gold 360 master mix (Applied Biosystems) with 400 nM each of amplification primers (5′- CAGCGCTGCCTGAAACTCG -3′ (sense) and 5′- CCACGTGGCGGAGGGACT -3′ (antisense)) resulting in a PCR product of 197 bp. Sequencing reactions were carried out on a high-throughput 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

HHV6 chromosomal integration

We amplified the sequences of the HHV6 major capsid protein and U94 genes in tumour and blood DNA from cases in the WGS and WES cohorts (n=37). PCR and cycling conditions followed a previously described protocol49,50. Cases positive by PCR were tested using the FISH analysis. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured for 72 h in RPMI 1640 containing 20% FCS and 10 μg ml−1 phytohemagglutinin (PHA). After 1.0 h of colcemide treatment, cells were harvested according to the standard cytogenetic techniques. Cells in the metaphase were examined with FISH using HHV6 cosmid probes labelled by nick translation with fluorescein-dUTP and a dual-colour probe mapped to the sequences 5′ and 3′ of the common breakpoint region within the MLL locus (11q23; Abbott Molecular). The HHV6/MLL probe mixture was applied to target metaphases and incubated at 37 °C overnight. After the slide was washed with 2 × SSC, 10 μl of 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstain was applied to the target area for visualization.

Additional information

Accession codes. All whole-genome sequencing, whole-exome sequencing and transcriptome data have been deposited in the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI), under accession code EGAS00001000192.

How to cite this article: Pinto, E. M. et al. Genomic landscape of paediatric adrenocortical tumours. Nat. Commun. 6:6302 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7302 (2015).

References

Ribeiro, R. C., Pinto, E. M., Zambetti, G. P. & Rodriguez-Galindo, C. The International Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumor Registry initiative: contributions to clinical, biological, and treatment advances in pediatric adrenocortical tumors. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 351, 37–43 (2012) .

Michalkiewicz, E. et al. Clinical and outcome characteristics of children with adrenocortical tumors: a report from the International Pediatric Adrenocortical Tumor Registry. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 838–845 (2004) .

Wasserman, J. D., Zambetti, G. P. & Malkin, D. Towards an understanding of the role of p53 in adrenocortical carcinogenesis. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 351, 101–110 (2012) .

Weksberg, R., Shuman, C. & Beckwith, J. B. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 8–14 (2010) .

Steenman, M., Westerveld, A. & Mannens, M. Genetics of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome-associated tumors: common genetic pathways. Genes Chromosome Cancer 28, 1–13 (2000) .

Ribeiro, R. C. et al. An inherited p53 mutation that contributes in a tissue-specific manner to pediatric adrenal cortical carcinoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9330–9335 (2001) .

Latronico, A. C. et al. An inherited mutation outside the highly conserved DNA-binding domain of the p53 tumor suppressor protein in children and adults with sporadic adrenocortical tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 4970–4973 (2001) .

Pinto, E. M. et al. Founder effect for the highly prevalent R337H mutation of tumor suppressor p53 in Brazilian patients with adrenocortical tumors. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 48, 647–650 (2004) .

Custódio, G. et al. Impact of neonatal screening and surveillance for the TP53 R337H mutation on early detection of childhood adrenocortical tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 2619–2626 (2013) .

Lau, S. K. & Weiss, L. M. The Weiss system for evaluating adrenocortical neoplasms: 25 years later. Hum. Pathol. 40, 757–768 (2009) .

Dehner, L. P. & Hill, D. A. Adrenal cortical neoplasms in children: why so many carcinomas and yet so many survivors? Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 12, 284–291 (2009) .

Michalkiewicz, E. L. et al. Clinical characteristics of small functioning adrenocortical tumors in children. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 28, 175–188 (1997) .

Clynes, D., Higgs, D. & Gibbons, R. J. The chromatin remodeller ATRX: a repeat offender in human disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38, 461–466 (2013) .

Letouzé, E. et al. SNP array profiling of childhood adrenocortical tumors reveals distinct pathways of tumorigenesis and highlights candidate driver genes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E1284–E1293 (2012) .

Forment, J. V., Kaidi, A. & Jackson, S. P. Chromothripsis and cancer: causes and consequences of chromosome shattering. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 663–670 (2012) .

Nik-Zainal, S. et al. Breast Cancer Working Group of the International Cancer Genome Consortium. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell 149, 979–993 (2012) .

Oren, M. Decision making by p53: life, death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 10, 431–442 (2003) .

Nichols, K. E. et al. Germ-line p53 mutations predispose to a wide spectrum of early-onset cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 10, 83–87 (2001) .

Ruijs, M. W. et al. TP53 germline mutation testing in 180 families suspected of Li- Fraumeni syndrome: mutation detection rate and relative frequency of cancers in different familial phenotypes. J. Med. Genet. 47, 421–428 (2010) .

Bischoff, F. Z. et al. Spontaneous abnormalities in normal fibroblasts from patients with Li-Fraumeni cancer syndrome: aneuploidy and immortalization. Cancer Res. 50, 7979–7984 (1990) .

Liu, P. K. et al. Analysis of genomic instability in Li-Fraumeni fibroblasts with germline p53 mutations. Oncogene 12, 2267–2278 (1996) .

Ehrlich, M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene 35, 5400–5413 (2002) .

Feinberg, A. P. & Tycko, B. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 143–153 (2004) .

Wasserman, J. D. et al. Prevalence and functional consequence of TP53 mutations in pediatric adrenocortical carcinoma: a Children’s Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol in press .

Smith, A. C. et al. Association of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma with the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 4, 550–558 (2001) .

Rainier, S. et al. Relaxation of imprinted genes in human cancer. Nature 362, 747–749 (1993) .

Mussa, A. et al. Neonatal hepatoblastoma in a newborn with severe phenotype of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Eur. J. Pediatr. 170, 1407–1411 (2011) .

Gicquel, C. et al. Structural and functional abnormalities at 11p15 are associated with the malignant phenotype in sporadic adrenocortical tumors: study on a series of 82 tumors. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82, 2559–2565 (1997) .

Assie, G. et al. Integrated genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 46, 607–612 (2014) .

Sun, F. L., Dean, W. L., Kelsey, G., Allen, N. D. & Reik, W. Transactivation of Igf2 in a mouse model of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nature 389, 809–815 (1997) .

Heaton, J. H. et al. Progression to adrenocortical tumorigenesis in mice andhumans through insulin-like growth factor 2 and β-catenin. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 1017–1033 (2012) .

Ehrlich, P. F. et al. Clinicopathologic findings predictive of relapse in children with stage III favorable-histology Wilms tumor. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 1196–1201 (2013) .

Parham, D. M. Pathologic classification of rhabdomyosarcomas and correlations with molecular studies. Mod. Pathol. 14, 506–514 (2001) .

Valentijn, L. J. et al. Functional MYCN signature predicts outcome of neuroblastoma irrespective of MYCN amplification. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 19190–19195 (2012) .

El Wakil, A. et al. Genetics and genomics of childhood adrenocortical tumors. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 336, 169–173 (2011) .

Magro, G. et al. Pediatric adrenocortical tumors: morphological diagnostic criteria and immunohistochemical expression of matrix metalloproteinase type 2 and human leucocyte-associated antigen (HLA) class II antigens. Results from the Italian Pediatric Rare Tumor (TREP) Study project. Hum. Pathol. 43, 31–39 (2012) .

Stratakis, C. A. Time to individualize treatment for adrenocortical cancer? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 76–78 (2014) .

Nacheva, E. P. et al. Human herpesvirus 6 integrates within telomeric regions as evidenced by five different chromosomal Sites. J. Med. Virol. 80, 1952–1958 (2008) .

Morissette, G. & Flamand, L. Herpesviruses and chromosomal integration. J. Virol. 84, 12100–12109 (2010) .

Huang, Y. et al. Human telomeres that carry an integrated copy of human herpesvirus 6 are often short and unstable, facilitating release of the viral genome from the chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 315–327 (2014) .

Chen, X. et al. Targeting oxidative stress in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell 24, 710–724 (2013) .

Zhang, J. et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 481, 157–163 (2012) .

Zhang, J. et al. A novel retinoblastoma therapy from genomic and epigenetic analyses. Nature 481, 329–334 (2012) .

Wang, J. et al. CREST maps somatic structural variation in cancer genomes with base-pair resolution. Nat. Methods 8, 652–654 (2011) .

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009) .

Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010) .

Pounds, S. et al. A genomic random interval model for statistical analysis of genomic lesion data. Bioinformatics 29, 2088–2095 (2013) .

Parker, M. et al. Assessing telomeric DNA content in pediatric cancers using whole-genome sequencing data. Genome Biol. 13, R113 (2012) .

Leite, J. L., Stolf, H. O., Reis, N. A. & Ward, L. S. Human herpesvirus type 6 and type 1 infection increases susceptibility to nonmelanoma skin tumors. Cancer Lett. 224, 213–219 (2005) .

Arbuckle, J. H. et al. The latent human herpesvirus-6A genome specifically integrates in telomeres of human chromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5563–5568 (2010) .

Acknowledgements

We thank the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital Hartwell Center, Tissue Resources Core Facility, Marc Valentine and the Cytogenetics Laboratory, and Pathology Department for expert assistance and Drs Charles Mullighan, Kathryn Roberts and Evan Parganas for assistance with figures. We thank Drs Gad B. Kletter, Andres Yunes and Ana Luisa Seidinger for clinical samples. We thank Sharon Naron for scientific edition. This work was supported by Cancer Center Support grant CA21765 and grants EY014867, EY018599 and CA168875 (M.A.D.) from the National Institutes of Health and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). Whole-genome sequencing was supported as part of the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital–Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. M.A.D. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P.Z., R.C.R., J.Z., E.M.P., X.C., E.R.M., R.K.W. and J.R.D. designed experiments or supervised research. M.J.M. provided samples. R.C.R. carried out chart review for clinical information. E.M.P., J.E., K.B., D.Y., J.C., T.C.L., J.M. and H.L.M. performed experiments. X.C., D.F., Z.L., J.Z. and S.P. performed the bioinformatics analyses. E.M.P., X.C., J.E., S.P., J.R.D., R.C.R., G.P.Z. and J.Z. analysed data. E.M.P., X.C. and R.C.R. prepared tables and figures. J.J. completed pathological evaluations. E.M.P., X.C., R.C.R. and G.P.Z. wrote the manuscript with contributions from C.R.G., B.C.F., M.A.D., A.P., J.Z. and J.R.D.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-10 and Supplementary Tables 1-5 (PDF 3689 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinto, E., Chen, X., Easton, J. et al. Genomic landscape of paediatric adrenocortical tumours. Nat Commun 6, 6302 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7302

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7302

This article is cited by

-

Pediatric adrenocortical carcinoma: clinical features and application of neoadjuvant chemotherapy

European Journal of Medical Research (2023)

-

Advances in translational research of the rare cancer type adrenocortical carcinoma

Nature Reviews Cancer (2023)

-

FLCN-Driven Functional Adrenal Cortical Carcinoma with High Mitotic Tumor Grade: Extending the Endocrine Manifestations of Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

Endocrine Pathology (2023)

-

Germline TP53 mutations undergo copy number gain years prior to tumor diagnosis

Nature Communications (2023)

-

CENPF/CDK1 signaling pathway enhances the progression of adrenocortical carcinoma by regulating the G2/M-phase cell cycle

Journal of Translational Medicine (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.