Abstract

Protected areas are one of the main tools for halting the continuing global biodiversity crisis1,2,3,4 caused by habitat loss, fragmentation and other anthropogenic pressures5,6,7,8. According to the Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 adopted by the Convention on Biological Diversity, the protected area network should be expanded to at least 17% of the terrestrial world by 2020 (http://www.cbd.int/sp/targets). To maximize conservation outcomes, it is crucial to identify the best expansion areas. Here we show that there is a very high potential to increase protection of ecoregions and vertebrate species by expanding the protected area network, but also identify considerable risk of ineffective outcomes due to land-use change and uncoordinated actions between countries. We use distribution data for 24,757 terrestrial vertebrates assessed under the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ‘red list of threatened species’9, and terrestrial ecoregions10 (827), modified by land-use models for the present and 2040, and introduce techniques for global and balanced spatial conservation prioritization. First, we show that with a coordinated global protected area network expansion to 17% of terrestrial land, average protection of species ranges and ecoregions could triple. Second, if projected land-use change by 2040 (ref. 11) takes place, it becomes infeasible to reach the currently possible protection levels, and over 1,000 threatened species would lose more than 50% of their present effective ranges worldwide. Third, we demonstrate a major efficiency gap between national and global conservation priorities. Strong evidence is shown that further biodiversity loss is unavoidable unless international action is quickly taken to balance land-use and biodiversity conservation. The approach used here can serve as a framework for repeatable and quantitative assessment of efficiency, gaps and expansion of the global protected area network globally, regionally and nationally, considering current and projected land-use pressures.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rodrigues, A. S. L. et al. Effectiveness of the global protected area network in representing species diversity. Nature 428, 640–643 (2004)

Butchart, S. H. M. et al. Protecting important sites for biodiversity contributes to meeting global conservation targets. PLoS ONE 7, e32529 (2012)

Thomas, C. D. et al. Protected areas facilitate species’ range expansions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14063–14068 (2012)

Le Saout, S. et al. Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation. Science 342, 803–805 (2013)

Butchart, S. H. M. et al. Global biodiversity: indicators of recent declines. Science 328, 1164–1168 (2010)

Hoffmann, M. et al. The impact of conservation on the status of the world’s vertebrates. Science 330, 1503–1509 (2010)

Gibson, L. et al. Primary forests are irreplaceable for sustaining tropical biodiversity. Nature 478, 378–381 (2011)

Laurance, W. F. et al. Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas. Nature 489, 290–294 (2012)

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013. 2 http://www.iucnredlist.org (2013)

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 51, 933–938 (2001)

van Asselen, S. & Verburg, P. H. Land cover change or land-use intensification: simulating land system change with a global-scale land change model. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 3648–3667 (2013)

Gaston, K. J. Global patterns in biodiversity. Nature 405, 220–227 (2000)

Brooks, T. M. et al. Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 313, 58–61 (2006)

Kremen, C. et al. Aligning conservation priorities across taxa in Madagascar with high-resolution planning tools. Science 320, 222–226 (2008)

Jenkins, C. N. & Joppa, L. Expansion of the global terrestrial protected area system. Biol. Conserv. 142, 2166–2174 (2009)

Joppa, L. N., Visconti, P., Jenkins, C. N. & Pimm, S. L. Achieving the convention on biological diversity’s goals for plant conservation. Science 341, 1100–1103 (2013)

Margules, C. R. & Pressey, R. L. Systematic conservation planning. Nature 405, 243–253 (2000)

Moilanen, A., Wilson, K. A. & Possingham, H. P. Spatial Conservation Prioritization: Quantitative Methods and Computational Tools (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009)

Hoekstra, J. M., Boucher, T. M., Ricketts, T. H. & Roberts, C. Confronting a biome crisis: global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecol. Lett. 8, 23–29 (2005)

Watson, J. E. M., Iwamura, T. & Butt, N. Mapping vulnerability and conservation adaptation strategies under climate change. Nature Clim. Change 3, 989–994 (2013)

Moilanen, A., Anderson, B. J., Arponen, A., Pouzols, F. M. & Thomas, C. D. Edge artefacts and lost performance in national versus continental conservation priority areas. Divers. Distrib. 19, 171–183 (2013)

IUCN & UNEP-WCMC. The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA). http://www.protectedplanet.net/ (2013)

Pereira, H. M. et al. Scenarios for global biodiversity in the 21st century. Science 330, 1496–1501 (2010)

Mascia, M. B. & Pailler, S. Protected area downgrading, downsizing, and degazettement (PADDD) and its conservation implications. Conserv. Lett. 4, 9–20 (2011)

Beger, M. et al. Conservation planning for connectivity across marine, freshwater, and terrestrial realms. Biol. Conserv. 143, 565–575 (2010)

Mokany, K., Harwood, T. D., Overton, J. M., Barker, G. M. & Ferrier, S. Combining α- and β-diversity models to fill gaps in our knowledge of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 14, 1043–1051 (2011)

Moss, R. H. et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463, 747–756 (2010)

Foden, W. B. et al. Identifying the world’s most climate change vulnerable species: a systematic trait-based assessment of all birds, amphibians and corals. PLoS ONE 8, e65427 (2013)

McCarthy, D. P. et al. Financial costs of meeting global biodiversity conservation targets: current spending and unmet needs. Science 338, 946–949 (2012)

Hunter, M. L. & Hutchinson, A. The virtues and shortcomings of parochialism: conserving species that are locally rare, but globally common. Conserv. Biol. 8, 1163–1165 (1994)

Wessel, P. & Smith, W. H. F. A global, self-consistent, hierarchical, high-resolution shoreline database. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 101, 8741–8743 (1996)

BirdLife International and NatureServe. Bird Species Distribution Maps of the World. Version 3. 0 http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/spcdownload (2013)

BirdLife International. BirdLife’s Global Species Programme. http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/species (2013)

Stuart, S. N. et al. Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306, 1783–1786 (2004)

Schipper, J. et al. The status of the world’s land and marine mammals: diversity, threat, and knowledge. Science 322, 225–230 (2008)

Gaston, K. J. & Fuller, R. A. The sizes of species’ geographic ranges. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 1–9 (2009)

Rondinini, C., Wilson, K. A., Boitani, L., Grantham, H. & Possingham, H. P. Tradeoffs of different types of species occurrence data for use in systematic conservation planning. Ecol. Lett. 9, 1136–1145 (2006)

Hurlbert, A. H. & Jetz, W. Species richness, hotspots, and the scale dependence of range maps in ecology and conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 13384–13389 (2007)

Jetz, W., Sekercioglu, C. H. & Watson, J. E. M. Ecological correlates and conservation implications of overestimating species geographic ranges. Conserv. Biol. 22, 110–119 (2008)

Cantú-Salazar, L. & Gaston, K. J. Species richness and representation in protected areas of the Western hemisphere: discrepancies between checklists and range maps. Divers. Distrib. 19, 782–793 (2013)

Rodrigues, A. S. L. et al. Global gap analysis: priority regions for expanding the global protected-area network. Bioscience 54, 1092–1100 (2004)

Jenkins, C. N., Pimm, S. L. & Joppa, L. N. Global patterns of terrestrial vertebrate diversity and conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E2602–E2610 (2013)

Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Impacts of incentives to reduce emissions from deforestation on global species extinctions. Nature Clim. Change 2, 350–355 (2012)

Venter, O. et al. Targeting global protected area expansion for imperiled biodiversity. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001891 (2014)

Böhm, M. et al. The conservation status of the world’s reptiles. Biol. Conserv. 157, 372–385 (2013)

Somveille, M., Manica, A., Butchart, S. H. M. & Rodrigues, A. S. L. Mapping global diversity patterns for migratory birds. PLoS ONE 8, e70907 (2013)

Rahbek, C. The role of spatial scale and the perception of large-scale species-richness patterns: scale and species-richness patterns. Ecol. Lett. 8, 224–239 (2005)

Schulman, L., Toivonen, T. & Ruokolainen, K. Analysing botanical collecting effort in Amazonia and correcting for it in species range estimation: Amazonian collecting and range estimation. J. Biogeogr. 34, 1388–1399 (2007)

OECD. OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050: The Consequences of Inaction. http://www.oecd.org/environment/oecdenvironmentaloutlookto2050theconsequencesofinaction.htm (2012)

Balmford, A., Green, R. & Phalan, B. What conservationists need to know about farming. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 2714–2724 (2012)

Laurance, W. F., Sayer, J. & Cassman, K. G. Agricultural expansion and its impacts on tropical nature. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 107–116 (2014)

Leathwick, J. R., Moilanen, A., Ferrier, S. & Julian, K. Complementarity-based conservation prioritization using a community classification, and its application to riverine ecosystems. Biol. Conserv. 143, 984–991 (2010)

Moilanen, A. et al. Zonation — Spatial Conservation Planning Methods and Software Version 4, User Manual (Univ. Helsinki, 2014)

Mendenhall, C. D., Karp, D. S., Meyer, C. F. J., Hadly, E. A. & Daily, G. C. Predicting biodiversity change and averting collapse in agricultural landscapes. Nature 509, 213–217 (2014)

Rondinini, C. et al. Global habitat suitability models of terrestrial mammals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 2633–2641 (2011)

Salafsky, N. et al. A standard lexicon for biodiversity conservation: unified classifications of threats and actions. Conserv. Biol. 22, 897–911 (2008)

Rodrigues, A. S. L. Improving coarse species distribution data for conservation planning in biodiversity-rich, data-poor, regions: no easy shortcuts. Anim. Conserv. 14, 108–110 (2011)

Arponen, A., Heikkinen, R. K., Thomas, C. D. & Moilanen, A. The value of biodiversity in reserve selection: representation, species weighting, and benefit functions. Conserv. Biol. 19, 2009–2014 (2005)

Lehtomäki, J. & Moilanen, A. Methods and workflow for spatial conservation prioritization using Zonation. Environ. Model. Softw. 47, 128–137 (2013)

Lehtomäki, J., Tomppo, E., Kuokkanen, P., Hanski, I. & Moilanen, A. Applying spatial conservation prioritization software and high-resolution GIS data to a national-scale study in forest conservation. For. Ecol. Manage. 258, 2439–2449 (2009)

Margules, C. & Sarkar, S. Systematic Conservation Planning (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007)

Kukkala, A. S. & Moilanen, A. Core concepts of spatial prioritisation in systematic conservation planning. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 88, 443–464 (2013)

Moilanen, A. Landscape zonation, benefit functions and target-based planning: unifying reserve selection strategies. Biol. Conserv. 134, 571–579 (2007)

Laitila, J. & Moilanen, A. Use of many low-level conservation targets reduces high-level conservation performance. Ecol. Modell. 247, 40–47 (2012)

Butchart, S. H. M. et al. Measuring global trends in the status of biodiversity: red list indices for birds. PLoS Biol. 2, e383 (2004)

Balmford, A., Gaston, K. J., Blyth, S., James, A. & Kapos, V. Global variation in terrestrial conservation costs, conservation benefits, and unmet conservation needs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1046–1050 (2003)

Moore, J., Balmford, A., Allnutt, T. & Burgess, N. Integrating costs into conservation planning across Africa. Biol. Conserv. 117, 343–350 (2004)

Naidoo, R. & Iwamura, T. Global-scale mapping of economic benefits from agricultural lands: Implications for conservation priorities. Biol. Conserv. 140, 40–49 (2007)

Eklund, J., Arponen, A., Visconti, P. & Cabeza, M. Governance factors in the identification of global conservation priorities for mammals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 2661–2669 (2011)

Waldron, A. et al. Targeting global conservation funding to limit immediate biodiversity declines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12144–12148 (2013)

Vincent, J. R. et al. Tropical countries may be willing to pay more to protect their forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10113–10118 (2014)

Rodrigues, A. S. L. & Gaston, K. J. Rarity and conservation planning across geopolitical units. Conserv. Biol. 16, 674–682 (2002)

Kark, S., Levin, N., Grantham, H. S. & Possingham, H. P. Between-country collaboration and consideration of costs increase conservation planning efficiency in the Mediterranean Basin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15368–15373 (2009)

Gustafsson, L. et al. Natural versus national boundaries: the importance of considering biogeographical patterns in forest conservation policy. Conserv. Lett. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/conl.12087 (13 February 2014)

Mazor, T., Possingham, H. P. & Kark, S. Collaboration among countries in marine conservation can achieve substantial efficiencies. Divers. Distrib. 19, 1380–1393 (2013)

Moilanen, A. & Arponen, A. Administrative regions in conservation: balancing local priorities with regional to global preferences in spatial planning. Biol. Conserv. 144, 1719–1725 (2011)

Mittermeier, R. A. et al. Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions (Conservation International, 2005)

Potapov, P. et al. Mapping the world’s intact forest landscapes by remote sensing. Ecol. Soc. 13, 51 (2008)

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858 (2000)

Davis, S. D., Heywood, V. H. & Hamilton, A. C. Centres of Plant Diversity. http://www.unep-wcmc.org/resources-and-data (2013)

Eken, G. et al. Key biodiversity areas as site conservation targets. Bioscience 54, 1110–1118 (2004)

Knight, A. T. et al. Improving the key biodiversity areas approach for effective conservation planning. Bioscience 57, 256–261 (2007)

BirdLife International, Conservation International, IUCN & UNEP-WCMC. Protected Area and Key Biodiversity Area. Data downloaded from the Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool (IBAT) https://www.ibat-alliance.org/ibat-conservation (2014)

Ambal, R. G. R. et al. Key biodiversity areas in the Philippines: priorities for conservation. J. Threat. Taxa 4, 2788–2796 (2012)

Conservation International. Priority Sites for Conservation in the Philippines: Key Biodiversity Areas. http://www.conservation.org/global/philippines/publications/Documents/KBA_Booklet.pdf (2006)

Tordoff, A. W., Baltzer, M. C., Fellowes, J. R., Pilgrim, J. D. & Langhammer, P. F. Key biodiversity areas in the Indo-Burma Hotspot: process, progress and future directions. J. Threat. Taxa 4, 2779–2787 (2012)

SAPM. Les sites du Système des Aires Protégées de Madagascar. Shapefile des sites du SAPM. Arrêté Interministériel n°9874/2013 Modifiant Certaines Dispositions de l’Arrêté n°52005/2010. http://atlas.rebioma.net/ (2014)

Jetz, W., McPherson, J. M. & Guralnick, R. P. Integrating biodiversity distribution knowledge: toward a global map of life. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 151–159 (2012)

Arponen, A., Lehtomäki, J., Leppänen, J., Tomppo, E. & Moilanen, A. Effects of connectivity and spatial resolution of analyses on conservation prioritization across large extents. Conserv. Biol. 26, 294–304 (2012)

Myers, J. L., Well, A. & Lorch, R. F. Research Design and Statistical Analysis. (Routledge, 2010)

Ficetola, G. F. et al. An evaluation of the robustness of global amphibian range maps. J. Biogeogr. 41, 211–221 (2014)

Acknowledgements

F.M.P., T.T., E.D.M., A.S.K., P.K., J.L. and A.M. thank the European Research Council Starting Grant (ERC-StG) 260393 (Global Environmental Decision Analysis, GEDA), the Academy of Finland centre of excellence programme 2012–2017 and the Natural Heritage Services (Metsähallitus) for support. P.H.V. thanks the ERC grant 311819 (GLOLAND). We thank A. Santangeli, I. Hanski and H. Tuomisto for comments on the manuscript, and CSC-IT Center for Science Ltd, administered by the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Finland, for its support and high-performance computing services. We are grateful for the efforts of data providers, IUCN, BirdLife International, Conservation International, the IUCN Species Survival Commission Specialist Groups and IUCN Red List Partners, the World Wildlife Fund, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, and their partners and contributors for kindly providing publicly available data, without which this and many other studies would not have been possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.M.P., T.T. and A.M. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all authors. F.M.P., T.T., E.D.M., J.L., P.K. and A.M. designed the study. A.M. conceived and led the study. F.M.P. and T.T. analysed the data and prepared the figures and tables. F.M.P. implemented prioritization algorithms and analyses. T.T., E.D.M., A.S.K., P.K., J.K., J.L., H.T. and F.M.P. collected and processed the data. P.H.V. contributed land-use models and data. T.T., E.D.M., A.S.K., P.K., J.K., J.L., H.T. and F.M.P. collected and processed the data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Original results data and additional interactive visualizations are available online at http://avaa.tdata.fi/web/cbig/.

Extended data figures and tables

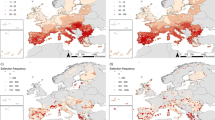

Extended Data Figure 1 Changes in spatial conservation priority between present and future (2040).

a–d, The top areas for PA expansion remain relatively stable: the congruence between priority expansion areas for present and projected future land use is 77.9%. Despite relatively high congruence (Supplementary Information), there are important localized differences. The biggest declines in priority would happen in China (d), India (c), eastern Europe and Turkey (b), whereas the changes are more subtle in sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas.

Extended Data Figure 2 Box plots of protection of effective range (species) and effective extent (ecoregions) in the expanded global PA system, under projected future (2040) land-use conditions.

a, b, Summaries of coverage for species grouped by taxonomic groups (classes) (a) and IUCN status (b). c, Ecoregions grouped by biome. These box plots show median values, twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentiles (boxes), whiskers (1.5 times the interquartile range) and outliers. Protection levels are well balanced for different species groups, and between species and ecoregions. Protection levels tend to be lower for less threatened species, as these tend to have wider ranges.

Extended Data Figure 3 Box plots of loss of effective range (species) and effective extent (ecoregions) from projected land-use changes by 2040.

a, Species grouped by taxonomic groups (classes), distinguishing small-range species (range size <50,000 km2). b, Species grouped by IUCN threat status. c, Ecoregions grouped by biome. The proportion of species that are expected to lose a significant fraction of their habitat is higher for species with a higher threat status.

Extended Data Figure 4 Comparison of priority areas for threatened species, and all species and ecoregions, both considering projected future land-use (2040).

a–d, The overall overlap of the respective top 17% priority areas is 62%. Priorities are highly congruent in most biodiversity hotspots of the world. More top priority areas are identified for threatened species in the tropics, whereas there are more top priority areas in higher latitudes for ecoregions and all vertebrate species. IUCN threat categories: critically endangered (CR), endangered (EN) and vulnerable (VU).

Extended Data Figure 5 Global expansion priority areas for projected future (2040) land-use.

a–d, Some of the areas in which the largest spatially contiguous overlaps occur are highlighted. Areas that overlap with biodiversity hotspots (full red) and those outside hotspots (green) are shown.

Extended Data Figure 6 Stacked bar plot showing the distributions of 17% expansion areas across different continents (left) and biomes (right), for future (2040) land-use.

When following national priorities, the distribution of expansion areas tends to be more balanced between biomes, at the expense of lower average protection of species and ecoregions, particularly favouring grasslands over tropical forests. The continental responsibility for Asia is virtually independent on whether national or global priorities are followed, whereas if planning is made nationally, responsibility clearly increases in Africa and North America and decrease in Central and South America. These patterns are stable across time (Supplementary Information).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text and Data 1-6, which include Supplementary Figures 1-56 and Supplementary Tables 1-24 – see Contents for more information. (PDF 10461 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montesino Pouzols, F., Toivonen, T., Di Minin, E. et al. Global protected area expansion is compromised by projected land-use and parochialism. Nature 516, 383–386 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14032

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14032

This article is cited by

-

The Impact of International Conservation Agreements on Protected Areas: Empirical Findings from the Convention on Biological Diversity Using Causal Inference

Environmental Management (2023)

-

Climate change–driven agricultural frontiers and their ecosystem trade-offs in the hills of Nepal

Regional Environmental Change (2023)

-

Multi-taxa spatial conservation planning reveals similar priorities between taxa and improved protected area representation with climate change

Biodiversity and Conservation (2022)

-

Reply to: Restoration prioritization must be informed by marginalized people

Nature (2022)

-

Incorporating Ecosystem Functional Diversity into Geographic Conservation Priorities Using Remotely Sensed Ecosystem Functional Types

Ecosystems (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.