Abstract

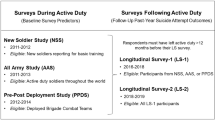

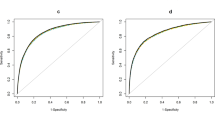

The 2013 US Veterans Administration/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guidelines (VA/DoD CPG) require comprehensive suicide risk assessments for VA/DoD patients with mental disorders but provide minimal guidance on how to carry out these assessments. Given that clinician-based assessments are not known to be strong predictors of suicide, we investigated whether a precision medicine model using administrative data after outpatient mental health specialty visits could be developed to predict suicides among outpatients. We focused on male nondeployed Regular US Army soldiers because they account for the vast majority of such suicides. Four machine learning classifiers (naive Bayes, random forests, support vector regression and elastic net penalized regression) were explored. Of the Army suicides in 2004–2009, 41.5% occurred among 12.0% of soldiers seen as outpatient by mental health specialists, with risk especially high within 26 weeks of visits. An elastic net classifier with 10–14 predictors optimized sensitivity (45.6% of suicide deaths occurring after the 15% of visits with highest predicted risk). Good model stability was found for a model using 2004–2007 data to predict 2008–2009 suicides, although stability decreased in a model using 2008–2009 data to predict 2010–2012 suicides. The 5% of visits with highest risk included only 0.1% of soldiers (1047.1 suicides/100 000 person-years in the 5 weeks after the visit). This is a high enough concentration of risk to have implications for targeting preventive interventions. An even better model might be developed in the future by including the enriched information on clinician-evaluated suicide risk mandated by the VA/DoD CPG to be recorded.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Deaths by suicide while on active duty, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 1998-2011. Med Surveill Monthly Rep 2012; 19: 7–10.

Nock MK, Deming CA, Fullerton CS, Gilman SE, Goldenberg M, Kessler RC et al. Suicide among soldiers: a review of psychosocial risk and protective factors. Psychiatry 2013; 76: 97–125.

Smolenski DJ, Reger MA, Bush NE, Skopp NA, Zhang Y, Campise RL . Department of Defense Suicide Event Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology 2013.

Zamorski MA . Suicide prevention in military organizations. Int Rev Psychiatry 2011; 23: 173–180.

Veterans Affairs/Dept of Defense. Assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide (2013). 2013.

Dawes RM, Faust D, Meehl PE . Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science 1989; 243: 1668–1674.

Grove WM, Zald DH, Lebow BS, Snitz BE, Nelson C . Clinical versus mechanical prediction: a meta-analysis. Psychol Assess 2000; 12: 19–30.

McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, Thompson C, Kemp J, Hannemann CM et al. Predictive modeling and concentration of the risk of suicide: implications for preventive interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: 1935–1942.

Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, Petukhova MV, Rose S, Bromet EJ et al. Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: the Army Study To Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 49–57.

Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB et al. The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry 2014; 77: 107–119.

Kessler RC, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gebler N, Naifeh JA, Nock MK et al. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2013; 22: 267–275.

Schlesselman JJ . Case-Control Studies: Design, Conduct, Analysis, 1st edn. Oxford University Press: New York, 1982.

Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR . Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68: 371–377.

Brugnoli R, Novick D, Haro JM, Rossi A, Bortolomasi M, Frediani S et al. Risk factors for suicide behaviors in the observational schizophrenia outpatient health outcomes (SOHO) study. BMC Psychiatry 2012; 12: 83.

Leadholm AK, Rothschild AJ, Nielsen J, Bech P, Ostergaard SD . Risk factors for suicide among 34,671 patients with psychotic and non-psychotic severe depression. J Affect Disord 2014; 156: 119–125.

Simon GE, Hunkeler E, Fireman B, Lee JY, Savarino J . Risk of suicide attempt and suicide death in patients treated for bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord 2007; 9: 526–530.

Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, Oliver M, Whiteside U, Operskalski B et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv 2013; 64: 1195–1202.

Simon GE, Savarino J, Operskalski B, Wang PS . Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 41–47.

Bachynski KE, Canham-Chervak M, Black SA, Dada EO, Millikan AM, Jones BH . Mental health risk factors for suicides in the US Army, 2007—8. Inj Prev 2012; 18: 405–412.

Bell NS, Harford TC, Amoroso PJ, Hollander IE, Kay AB . Prior health care utilization patterns and suicide among U.S. Army soldiers. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2010; 40: 407–415.

Black SA, Gallaway MS, Bell MR, Ritchie EC . Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicides of Army soldiers 2001–2009. Mil Psychol 2011; 23: 433–451.

Gilman SE, Bromet EJ, Cox KL, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gruber MJ et al. Sociodemographic and career history predictors of suicide mortality in the United States Army 2004-2009. Psychol Med 2014; 44: 2579–2592.

Hyman J, Ireland R, Frost L, Cottrell L . Suicide incidence and risk factors in an active duty US military population. Am J Public Health 2012; 102 (Suppl 1): S138–S146.

Ireland RR, Kress AM, Frost LZ . Association between mental health conditions diagnosed during initial eligibility for military health care benefits and subsequent deployment, attrition, and death by suicide among active duty service members. Mil Med 2012; 177: 1149–1156.

Schoenbaum M, Kessler RC, Gilman SE, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB et al. Predictors of suicide and accident death in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS): results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71: 493–503.

Street AE, Gilman SE, Rosellini AJ, Stein MB, Bromet EJ, Cox KL et al. Understanding the elevated suicide risk of female soldiers during deployments. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 717–726.

FDB Health. FDB First Databank, 2015. Available at: http://www.fdbhealth.com (accessed on 1 October, 2015).

SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT Software. 9.3 for Unix edn.

Rish I . An Empirical Study of the Naive Bayes Classifier. IBM Research Division: Yorktown Heights, NY, 2001.

Meyer D, Dimitriadou E, Hornik K, Weingessel A, Leisch F, Chang CC et al Package 'e1071': misc functions of the Department of Statistics, Probability Theory Group, TU Wien. 1.5-7 edn 2015.

Breiman L . Random Forests. Mach Learn 2001; 45: 5–32.

Liaw A, Wiener M . Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002; 2: 18–22.

Smola AJ, Scholkopf B . A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat Comput 2004; 14: 199–222.

Zou H, Hastie T . Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J R Stat Soc B 2005; 67: 301–320.

Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R . Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw 2009; 33: 1–22.

Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, Beck A, Waitzfelder BE, Rossom R et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29: 870–877.

Large MM, Ryan CJ . Suicide risk categorisation of psychiatric inpatients: what it might mean and why it is of no use. Australas Psychiatry 2014; 22: 390–392.

O'Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, Whitlock EP . Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158: 741–754.

While D, Bickley H, Roscoe A, Windfuhr K, Rahman S, Shaw J et al. Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997-2006: a cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. Lancet 2012; 379: 1005–1012.

Berrouiguet S, Gravey M, Le Galudec M, Alavi Z, Walter M . Post-acute crisis text messaging outreach for suicide prevention: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res 2014; 217: 154–157.

Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, Zivin K, Austin KL et al. Higher-risk periods for suicide among VA patients receiving depression treatment: prioritizing suicide prevention efforts. J Affect Disord 2009; 112: 50–58.

LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, Bell MR, Smith B, Boyko EJ et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel. JAMA 2013; 310: 496–506.

Brenner LA, Ignacio RV, Blow FC . Suicide and traumatic brain injury among individuals seeking Veterans Health Administration services. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2011; 26: 257–264.

Nowrangi MA, Kortte KB, Rao VA . A perspectives approach to suicide after traumatic brain injury: case and review. Psychosomatics 2014; 55: 430–437.

Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Skopp NA, Metzger-Abamukang MJ, Kang HK, Bullman TA et al. Risk of suicide among US military service members following operation enduring freedom or operation Iraqi freedom deployment and separation from the US military. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 561–569.

Erdman HP, Greist JH, Gustafson DH, Taves JE, Klein MH . Suicide risk prediction by computer interview: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48: 464–467.

Gustafson DH, Greist JH, Stauss FF, Erdman H, Laughren T . A probabilistic system for identifying suicide attemptors. Comput Biomed Res 1977; 10: 83–89.

Gustafson DH, Tianen B, Greist JH . A computer-based system for identifying suicide attemptors. Comput Biomed Res 1981; 14: 144–157.

Acknowledgements

Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 with the US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). Dr Gilman’s participation in this work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We thank Kenneth L Cox for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. Although a draft of this manuscript was submitted to the Army and NIMH for review and comment before submission, this was with the understanding that comments would be no more than advisory.

Author contributions

The Army STARRS Team Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J Ursano (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B Stein (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System); Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa (University of Michigan) and Ronald C Kessler (Harvard Medical School); NIMH collaborating scientists: Lisa J Colpe and Michael Schoenbaum; Army liaisons/consultants: COL Steven Cersovsky (USAPHC) and Kenneth Cox (USAPHC). Other team members: Pablo A Aliaga (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); David M. Benedek (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Susan Borja (National Institute of Mental Health); Gregory G Brown (University of California San Diego); Laura Campbell-Sills (University of California San Diego); Catherine L Dempsey (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Richard Frank (Harvard Medical School); Carol S Fullerton (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler (University of Michigan); Robert K Gifford (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Stephen E Gilman (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Harvard School of Public Health); Marjan G Holloway (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Paul E Hurwitz (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Karestan C Koenen (Columbia University); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James E McCarroll (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Katie A McLaughlin (Harvard Medical School); James A Naifeh (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K Nock (Harvard University); Rema Raman (University of California San Diego); Sherri Rose (Harvard Medical School); Anthony Joseph Rosellini (Harvard Medical School); Nancy A Sampson (Harvard Medical School); LCDR Patcho Santiago (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Michaelle Scanlon (National Institute of Mental Health); Jordan Smoller (Harvard Medical School); Michael L Thomas (University of California San Diego); Patti L Vegella (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Christina Wassel (University of Pittsburgh); and Alan M Zaslavsky (Harvard Medical School). We also thank John Mann, Maria Oquendo, Barbara Stanley, Kelly Posner and John Keilp for their contributions to the early stages of Army STARRS development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

In the past 3 years, Dr Kessler has been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche and Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention. Dr Kessler has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Johnson & Johnson Services, Lake Nona Life Project and US Preventive Medicine. Dr Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat. Dr Stein has in the last 3 years been a consultant for Healthcare Management Technologies and had research support for pharmacologic imaging studies from Janssen. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Disclosure

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kessler, R., Stein, M., Petukhova, M. et al. Predicting suicides after outpatient mental health visits in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Mol Psychiatry 22, 544–551 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.110

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.110