Abstract

It is believed that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps lead to the development of microsatellite unstable cancer via a dysplasia-carcinoma sequence. Little is known regarding the morphologic and biologic features, and outcome of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia, or of its specific dysplasia subtypes (intestinal versus serrated). The aims of this study were to analyze and compare the clinical, pathologic, and outcome characteristics of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated versus intestinal dysplasia. The study included 86 patients with sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia (50 serrated dysplasia, 22 intestinal dysplasia, 14 mixed serrated and intestinal dysplasia). The clinical and pathologic features, and the prevalence rate of prior, concurrent, and future neoplastic lesions, were compared between sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal versus serrated dysplasia and with matched control patients with ≥1 conventional adenoma. The mean age of the patients, polyp size, and prevalence of adenocarcinoma within the polyps were significantly higher in sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with high versus low-grade dysplasia. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia showed a significantly higher rate of adenocarcinoma (23%) compared with those with serrated dysplasia (6%, P=0.05), and the high-grade lesions occurred at a significantly younger age in the former compared with the latter (65 versus 76 years, P=0.05). Compared with patients with conventional adenomas, patients with sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia showed a significantly higher rate of invasive carcinoma within the polyps (12 versus 0%, P=0.01) and a significantly lower association with prior or future conventional adenomas. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia should be considered high-risk neoplastic precursor lesions, particularly those with intestinal dysplasia. Cancer may develop from sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with either type of dysplasia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Adenocarcinoma of the colon develops via one of two main molecular pathways. The most common is the chromosomal instability pathway, which is characterized by tumors with a high degree of chromosomal instability and a high prevalence rate of APC, KRAS, and TP53 mutations.1 This pathway develops via malignant transformation of conventional (tubular, tubulovillous, or villous) adenomas. Conventional adenomas are dysplastic precursor lesions that show fairly uniform nuclear cytologic features. Neoplastic nuclei generally appear enlarged and hyperchromatic, contain clumped chromatin, are elongated or pencil-shaped, and show a variable degree of goblet cell or enterocyte differentiation. By convention, these features are considered 'adenomatous' or 'intestinal-type' dysplasia, because the cells appear to differentiate toward an intestinal phenotype. The second is the microsatellite instability pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis, which is characterized by distinct molecular genetic and epigenetic signatures, such as CpG island methylation, BRAF mutations, and microsatellite instability.2, 3 Approximately 15% of colorectal carcinomas show microsatellite instability. A minor subset of all colorectal carcinomas arise from malignant transformation of serrated precursor polyps.4

There are three general categories of serrated polyps: hyperplastic polyp, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, either with or without dysplasia, and traditional serrated adenoma.5 It is believed that microsatellite unstable cancers develop via dysplastic transformation of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp.2, 3 However, some may develop from traditional serrated adenoma, but those are much less common.6 Unlike conventional adenomas, serrated polyps may develop two distinct morphologic types of dysplasia.3, 5, 7, 8, 9 The first is intestinal dysplasia, similar to that which occurs in conventional adenomas, and the second is serrated dysplasia, which is characterized by epithelium with enlarged oval to slightly elongated cells with an open nuclear chromatin pattern, prominent nucleoli, and eosinophilic cytoplasm. This type of dysplasia can also show a variable number of goblet cells, but the main distinguishing feature from intestinal dysplasia is the characteristic luminal serrated (saw-toothed) growth pattern of the epithelium. Unfortunately, little is known of the morphologic and biological features, associated conditions, and outcome of serrated polyps with either intestinal or serrated dysplasia. Prior studies have either not sufficiently categorized sessile serrated adenomas/polyps into those with intestinal versus serrated dysplasia, or not used consistent and reproducible morphologic criteria in doing so.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Some studies suggest that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia are at higher risk for progression to carcinoma, but little is known of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated dysplasia and its biological capacity for progression.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Therefore, the aims of this study were to fully characterize the spectrum of dysplasia in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, and to analyze and compare the clinicopathologic and outcome characteristics of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated versus intestinal dysplasia.

Materials and methods

Study Group

The study cohort consisted of 86 sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia from 86 patients, all of whom were identified via a search through the electronic medical records of two major hospitals (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, and Yale-New Haven Hospital, New Haven, CT, USA) between the years 2004 and 2015. Search terms used to find cases included 'sessile serrated adenoma', 'serrated adenoma', 'mixed hyperplastic/adenomatous polyp', 'sessile serrated adenoma (or polyp) with dysplasia', and sessile serrated adenoma (or polyp) with atypia'. Initially, 211 potential cases were identified, but after careful review of the pathology reports, only 137 cases were determined to represent sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia. Of these 137 cases, 51 were excluded because they either did not have histology slides available for analysis, or upon histologic review of the slides by the authors, the sessile serrated adenoma/polyp and dysplastic epithelium were not present in the same tissue fragments. Therefore, the development of dysplasia arising directly from a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp could not be determined with complete certainty. Of the final 86 patients, the medical records, clinical notes, and endoscopy reports were evaluated for a variety of features, such as patient age and gender, polyp size (cm), and anatomic location in the colon (right versus left). All prior, concurrent, and future pathology was reviewed and evaluated for the presence, type, and number of neoplastic precursor lesions (both serrated and conventional) in other portions of the colon, and for adenocarcinoma. The follow-up interval was calculated from the time of the patients' index sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia to the time of the patients' most recent follow-up endoscopy examination. A control group of patients with ≥1 conventional adenoma (N=56) was selected within the same time period (2004–2015). These patients were matched to the sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia group using the method of frequency matching for patient gender and age, polyp size and anatomic location in the colon, and for the proportion of polyps with low or high-grade dysplasia.14 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Histologic Methods

By utilizing the histologic criteria outlined below, the 86 study polyps were divided into three categories: (1) Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated dysplasia, (2) sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia, and (3) sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with a mixture of a serrated and intestinal dysplasia. Each polyp was also categorized for the highest grade of dysplasia (low or high) according to predetermined pathologic criteria outlined below, and for the presence or absence of intramucosal or invasive adenocarcinoma.

As mentioned above, all lesions were categorized according to their type (intestinal versus serrated) and grade (low versus high grade) of dysplasia according to criteria previously reported.5, 15 In brief, intestinal dysplasia is composed of epithelium with cells that show elongated pencil-shaped and hyperchromatic nuclei, clumped chromatin, and nuclear stratification, increased mitotic figures, and amphophilic cytoplasm. Cells may show a variable degree of goblet or enterocyte-like differentiation. Low-grade intestinal dysplasia shows epithelium without architectural aberrations (absence of back-to-back glands, cribriforming and gland-in-gland formation) and an absence of high-grade cytologic features as described further below. High-grade intestinal dysplasia shows high-grade cytologic and/or architectural aberrations. Cytologic features of high-grade dysplasia include enlarged, round or irregular-shaped nuclei, with irregular nuclear membranes, open chromatin, increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, marked pleomorphism, and loss of polarity. Full thickness stratification is also a high-grade feature.

In contrast to intestinal dysplasia, serrated dysplasia is composed of epithelial cells with oval to slightly elongated nuclei with an open chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli. The nuclear membranes are typically smooth in contour. The nuclei are smaller in size than in intestinal dysplasia and show less pronounced stratification. The cytoplasm is eosinophilic. A variable number of goblet cells may be present as well. The characteristic architectural feature of serrated dysplasia is the presence of luminal serration or saw-toothed pattern of growth, which is often more pronounced in the upper portion of the crypts and surface epithelium compared with the bases of the crypts. Increased mitotic figures (including atypical mitotic forms) may occur in serrated dysplasia as well. High-grade serrated dysplasia shows high-grade cytologic and/or architectural aberrations. Cytologic features of high-grade serrated dysplasia include enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei with a more pronounced clumped chromatin pattern, increased nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, loss of polarity, and full-thickness stratification. This is usually associated with architectural aberrations such as back-to-back gland formation, gland-in-gland formation, and/or a hyperserrated growth pattern. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with mixed (intestinal and serrated) dysplasia were defined as lesions that contained both morphologic types of dysplasia within the same lesion.

Statistical Methods

The Fisher's exact test and the unpaired t-test were used for statistical analysis and comparisons. All reported P-values are two-tailed. A P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical and Pathologic Results

Table 1 outlines the clinical and pathologic features of the sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia included in this study. Overall, there were 86 polyps from 86 patients (29 males and 57 females of mean age 63.2 years, range: 21–95 years). Most polyps were located in the right colon (N=79) versus the left (N=7), and had a mean size of 1.0 cm (range: 0.3-4.4 cm). Fifty-nine polyps (69%) had only low-grade dysplasia and 27 (31%) had high-grade dysplasia. Fourteen polyps (16%) contained adenocarcinoma, which was intramucosal in four and submucosally invasive in 10. Of the four intramucosal carcinomas, one was present in a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with intestinal dysplasia and three in a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with mixed dysplasia. Of the 86 polyps, 48 were treated with complete endoscopic polypectomy (with negative margins), and 38 were initially biopsied and then subsequently resected by either complete endoscopic polypectomy or segmental colectomy within 6 months. Of the 10 submucosally invasive adenocarcinomas, 8 were treated with a segmental colectomy (final AJCC pathologic stage; T1N0 n=5, T3N0 n=2, and T1N1 n=1) and 2 were managed with complete endoscopic polypectomy (final AJCC pathologic stage; T1Nx n=2). Overall, both the mean age of the patients (70.3 versus 59.9 years), and the mean size of the polyps (1.5 cm versus 0.9 cm), were significantly higher in polyps that contained high-grade versus low-grade dysplasia (P=0.01 for both comparisons). Furthermore, cancer occurred significantly more often (14/27, 52%) in polyps with high-grade dysplasia in comparison with those with only low-grade dysplasia (0/59, 0%, P=0.01). In fact, cancer occurred only in polyps with high-grade dysplasia.

Table 1 also summarizes the clinical and pathologic features of the sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia separated into the three dysplasia subgroups. Of the 86 polyps, 50 contained pure serrated dysplasia (58%), 22 contained pure intestinal dysplasia (26%), and 14 contained mixed dysplasia (16%) (Figures 1 and 2). Within polyp subgroup, patients with high-grade dysplasia were older than patients with low-grade dysplasia, but these comparisons reached statistical significance only for the patients with pure serrated dysplasia (75.75 years versus 58.16 years, P=0.01). Interestingly, patients with high-grade serrated dysplasia were significantly older than patients with high-grade intestinal dysplasia (75.75 years versus 65.0 years, P=0.05). There were no significant differences in the male/female ratio, mean size, or anatomic location among polyps with serrated versus intestinal or mixed dysplasia. However, polyps with intestinal dysplasia, or mixed serrated and intestinal dysplasia, showed a significantly higher association with adenocarcinoma compared with polyps with pure serrated dysplasia. For instance, only 3 of 50 patients with serrated dysplasia (6%) were associated with adenocarcinoma, compared with 5/22 (23%) polyps with pure intestinal dysplasia and 6/14 (43%) polyps with mixed dysplasia (P=0.05 and 0.01, respectively).

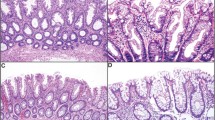

(a–d) Low and high-grade intestinal dysplasia in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. (a) (low magnification) and (b) (high magnification): low-grade intestinal dysplasia shows tubular proliferation of neoplastic epithelium composed of cells with hyperchromatic elongated nuclei and basal stratification. The cytoplasm shows enterocyte-like and goblet cell differentiation. (c) (low magnification) and (d) (high magnification): high-grade intestinal dysplasia shows more severe cytologic atypia. The epithelium shows larger, more hyperchromatic nuclei and more stratification. The epithelium also shows gland-in-gland and back-to-back gland patterns. Goblet cells are fewer in number.

(a–d) Low and high-grade serrated dysplasia in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (a) (low magnification) and (b) (high magnification): low-grade serrated dysplasia shows a tubulovillous proliferation of neoplastic epithelium composed of round to oval-shaped nuclei with hyperchromatism and slight stratification. The cytoplasm is hypereosinophilic and shows rare goblet cells. Architecturally, the epithelium shows luminal infolding and serration similar to that seen in non-dysplastic sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. (c) (low magnification) and (d) (high magnification): high-grade serrated dysplasia. The epithelium shows larger nuclei that are more elongate, with increased stratification, and more abundant mitotic figures. Architecturally, the epithelium shows a more prominent back-to-back gland pattern and more pronounced luminal infolding and serration. The cytoplasm shows few, if any, goblet cells.

Finally, separate comparisons were made between sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated dysplasia and both sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with mixed serrated and intestinal dysplasia, the latter combined group representing sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia, regardless of whether it was pure or mixed with serrated dysplasia. In this analysis, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with intestinal dysplasia, regardless of whether it was pure or mixed with serrated dysplasia, showed a significantly higher mean patient age (66.25 years versus 60.98 years, P=0.05), and a significantly higher rate of adenocarcinoma compared with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with pure serrated dysplasia (11/36; 31% versus 3/50; 6%, P=0.01).

Pathologic Associations and Follow-up Data

Table 2 summarizes the prevalence rate and type of prior or concurrent (synchronous), and follow-up polyps, and carcinoma, in the study group of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia versus control patients with ≥1 conventional adenoma. Pathologically, a significantly higher proportion of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia were associated with invasive adenocarcinoma within the polyp (10/86, 12%) versus conventional adenomas (0/56, 0%, P=0.01). Regarding prior or concurrent lesions in these two patient groups, patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia showed a significantly lower rate of prior or concurrent polyps versus those with conventional adenomas (P=0.01). Furthermore, patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia showed a significantly lower rate of either prior or concurrent conventional adenomas (41%) compared with the conventional adenoma control group (89%, P=0.01), but no differences were noted in the rate or type of prior or concurrent serrated polyps or adenocarcinoma. Upon follow up, a similar pattern was noted. Patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia showed a significantly lower rate of future polypoid lesions in general (56%), and of conventional adenomas specifically (41%), versus control patients (90 and 72% respectively, P<0.05 for both comparisons), but no differences in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp or traditional serrated adenoma formation, and no differences in the rate of future adenocarcinoma development elsewhere in the colon.

Table 3 summarizes and compares the prevalence rate and type of prior, concurrent, and follow-up lesions in each of the three dysplasia subgroups. Patients with intestinal dysplasia showed a significantly higher rate of prior and/or concurrent polyps in general (91%) versus patients with serrated dysplasia (68%, P=0.04). However, overall, there were no significant differences in the prevalence rate or type of prior, concurrent, or follow-up polyps or adenocarcinoma between the three dysplasia subgroups. After comparing this data between sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with pure serrated dysplasia versus sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with intestinal dysplasia, the latter either pure or mixed with serrated dysplasia, no significant differences emerged as well.

Discussion

Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp is the main precursor lesion of at least 15% of colorectal carcinomas, but their biology is poorly understood.3 Despite early observations by Goldstein et al7 and Jass et al9 that precursors of microsatellite instability-high and/or CpG island methylator phenotype-high colon cancer show features of serrated dysplasia in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, this type of dysplasia has never been studied systematically, nor has it been analyzed in comparison with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with intestinal dysplasia. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to characterize the spectrum of dysplasia in sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, and to analyze and compare the clinicopathologic and outcome characteristics of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated versus intestinal (or mixed) dysplasia. Our results showed that the most common type of dysplasia in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp is serrated, and this is followed in order of frequency by intestinal and mixed. Overall, the mean age of the patients, the mean size of the polyps, and the prevalence rate of adenocarcinoma within the polyps, were all significantly higher in sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with high-grade versus low-grade dysplasia. These data, combined with our finding that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated dysplasia have a significantly lower rate of adenocarcinoma within the polyp compared with sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal (or mixed intestinal and serrated) dysplasia, support the low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia to adenocarcinoma carcinogenic pathway in these polyps, and also suggest that intestinal dysplasia in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp is a higher risk feature for the development of carcinoma in these polyps. Interestingly, although both low-grade serrated and low-grade intestinal dysplasia were detected at a similar mean patient age, the time interval for the development of high-grade dysplasia was shorter in patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with intestinal dysplasia than those with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with serrated dysplasia. This finding suggests a faster rate of malignant transformation in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with intestinal dysplasia. With regard to the biology of serrated versus intestinal dysplasia, we did not find any differences in gender, size, or location of polyps, or in the type of polyps or adenocarcinoma development elsewhere in the colon, between the various dysplasia subgroups. Interestingly, we did find a significantly higher rate of invasive cancer in sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia compared with conventional adenomas (P=0.01), which suggests the possibility that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia are higher risk lesions than conventional adenomas. Based on these results, we conclude that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia should be considered high-risk neoplastic precursor lesions, particularly those with intestinal dysplasia.

Our study is the first to critically evaluate and compare the clinical and pathologic features of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with either serrated or intestinal dysplasia. However, several other studies of 'high risk' sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia or carcinoma, that were designed to evaluate other factors, have made some similar observations to those in our current study.7, 8, 13, 15, 16, 17 For instance, several studies have also documented two types of dysplasia (serrated and intestinal) in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, and have also shown data that support the low to high-grade dysplasia to carcinoma pathogenetic sequence.7, 8, 12 In a study by Lash et al12 in 2010, of 2139 patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, 12% had low-grade dysplasia, 2% had high-grade dysplasia and 1% adenocarcinoma. Similar to the results of our study, Lash et al found that patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia were more common in women than men, the lesions were located more often in the right than the left colon, and, most interestingly, the mean age of the patients increased significantly from patients with low to high-grade dysplasia to adenocarcinoma. Unfortunately, in that study, the authors did not separate dysplasia into serrated versus intestinal type, but they did note that 'rarely dysplasia resembled that of a traditional serrated adenoma', which suggests that at least some of their dysplastic sessile serrated adenomas/polyps had a serrated rather than an intestinal dysplasia phenotype. In 2006, Goldstein et al in a study of eight cases of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with either high-grade dysplasia (n=2) or invasive adenocarcinoma (n=6) noted that all polyps had serrated dysplasia, but none had 'APC-type adenomatous dysplasia' which corresponds to intestinal dysplasia in our study.7 Finally, in a study by Fujita et al in 2011, 12 cases of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with either high-grade dysplasia (n=7) or submucosally invasive adenocarcinoma (n=5) were compared with sessile serrated adenomas/polyps without dysplasia (n=53) and 66 control hyperplastic polyps.8 The primary purpose of that study was to evaluate the molecular features of these polyps by immunohistochemistry and gene mutation analysis. However, the authors of that study did note that 9/12 (75%) of polyps showed a 'tubulovillous' dysplasia phenotype, and 7/12 (58%) showed mixed serrated and intestinal features, where in the latter, one pattern was typically predominant over the other. Several other small case series that documented various clinical and pathologic features of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia and/or carcinoma7, 15, 16, 17 also provided data supporting the dysplasia-carcinoma sequence in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, and that this process occurs in polyps of small size and potentially with rapid progression.

One of the other key findings in our study is that compared with control conventional adenomas (matched for size, anatomic location, and degree of dysplasia), sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia showed a significantly higher prevalence rate of invasive carcinoma within the polyp. This finding is consistent with the results of several previously published outcome studies of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps and further supports the hypothesis made initially by other investigators8, 9, 10, 13, 18 that these are potentially higher risk polyps, as they develop cancer more rapidly, and at a smaller size, than conventional adenomas.4, 11, 19 As mentioned above, we did document a significantly higher rate of adenocarcinoma in sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia versus serrated dysplasia, which suggests that lesions with an intestinal dysplasia phenotype may progress faster than those with a serrated phenotype. Interestingly, in one case report of a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp that progressed to invasive cancer within 8 months, the precursor dysplastic component (represented in a photograph in that article), shows intestinal/tubular morphology rather than serrated morphology.11 In our study, we did not detect a significant difference in the development of extrapolypoid adenocarcinoma upon follow-up in patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia versus our control patients with conventional adenomas, or a difference in outcome between patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with serrated versus intestinal dysplasia. However, the small number of cases in our study, and the rather short follow-up period of time, may have limited our ability to detect a potential association, and this clearly should be addressed further in future studies with a larger number of cases and within longer follow-up times.

Based on our clinical and morphologic observations in this study, and on the basis of several studies that have evaluated immunohistochemical and molecular features in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia, there is some data to support the possibility that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps may develop cancer by two distinct morphologic/molecular pathways.8, 9, 13, 20 The data to support this concept stems from studies that have either evaluated the types and frequency of prior, synchronous, and metachronous lesions in patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, or from studies that have evaluated molecular features in these lesions.8, 9, 10, 13, 20 Regarding synchronous or metachronous neoplasia, in our study, we showed that our control patients with conventional adenomas revealed a significant association with both prior/concurrent and follow-up conventional adenomas, compared with patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia. In the only other study that evaluated these pathologic associations, in 2005 Lazarus et al10 compared the prevalence and type of metachronous lesions, upon follow-up, in patients with serrated adenomas, conventional adenomas and hyperplastic polyps, but they did not evaluate patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia specifically. Some of the photographs of 'serrated adenomas' in that study showed features suggestive of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia and traditional serrated adenoma based on the current WHO criteria.5 Nevertheless, the authors showed a strong correlation between the type of index polyp (serrated adenoma versus conventional adenoma versus hyperplastic polyp) and type of polyp that developed upon follow-up. In fact, the risk of cancer development was slightly higher in the patients with serrated adenomas versus conventional adenomas, which is similar to the results in our study where we detected a higher rate of invasive cancer in sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia compared with conventional adenomas.

With regard to future risk of adenocarcinoma, our study failed to detect a significant difference in the development of adenocarcinoma upon follow-up in patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia compared with those with conventional adenomas, and in patients with sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated versus intestinal dysplasia. However, the small number of cases in our study, and the relatively short follow-up time, make it possible that this may be due to type II statistical error. One prior study by Lu et al reported that patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp had a higher incidence of future colorectal adenocarcinoma compared with control patients with conventional adenomas (12.5 versus 1.8%), but that study did not separate sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia into those with serrated or intestinal morphology.19 In contrast, outcome differences with regard to cancer development were not confirmed in the study by Lazarus et al,10 mentioned above, with long term follow-up. In that study, a similar incidence of future adenocarcinoma was detected in patients with 'serrated adenomas' and 'conventional adenomas' (5% versus 2.2%).

Our study suffered from limitations mainly owing to its retrospective design. In addition, only 22 sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia and only 14 with mixed dysplasia were identified from our pathology files, which, again, may have resulted in type II statistical error when evaluating features in comparison with the serrated dysplasia subgroup. This is a reflection of the rarity of dysplasia in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, as supported by the study by Lash et al12 noted above. Regardless, our current study is the largest to date of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia, and the only one to evaluate specifically differences in subtypes of dysplasia. Our follow-up time was also limited, which may have resulted in a low incidence rate of adenocarcinoma development. Finally, many of our patients had lesions detected at a time when there was less awareness of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp and the difficulties surrounding its endoscopic detection so that errors may have occurred with regard to our data on prior or concurrent lesions.

In summary, we found that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia contain two broad types of dysplasia, serrated and intestinal, and some show a mixture of both of these features. In comparison with conventional adenomas, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia showed a significantly higher risk of malignant transformation within the polyp. We also found that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with intestinal dysplasia show a higher risk of cancer within the polyp compared with those with serrated dysplasia, which may indicate that intestinal dysplasia is a particularly high-risk feature in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. Finally, our findings support the low to high-grade dysplasia to carcinoma pathogenetic sequence in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. Further studies should be done to determine whether treatment decisions, and surveillance intervals, should be altered for patients with sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with serrated versus intestinal dysplasia, the latter possibly warranting more complete and closer follow-up than the former.

References

Vogelstein BM, Fearon ERB, Hamilton SRM et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med 1988;319:525–532.

Jass JR . Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology 2007;50:113–130.

Snover DC . Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2011;42:1–10.

Makinen MJ, George SM, Jernvall P et al. Colorectal carcinoma associated with serrated adenoma - prevalence, histological features, and prognosis. J Pathol 2001;193:286–294.

Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW et alSerrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban R (eds) WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System. Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA, USA, 2010;160–165.

Bettington ML, Chetty R . Traditional serrated adenoma: an update. Hum Pathol 2015;46:933–938.

Goldstein NS . Small colonic microsatellite unstable adenocarcinomas and high-grade epithelial dysplasias in sessile serrated adenoma polypectomy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;125:132–145.

Fujita K, Yamamoto H, Matsumoto T et al. Sessile serrated adenoma with early neoplastic progression: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:295–304.

Jass JR, Baker K, Zlobec I et al. Advanced colorectal polyps with the molecular and morphological features of serrated polyps and adenomas: Concept of a “fusion” pathway to colorectal cancer. Histopathology 2006;49:121–131.

Lazarus R, Junttila OE, Karttunen TJ et al. The risk of metachronous neoplasia in patients with serrated adenoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;123:349–359.

Oono Y, Fu K, Nakamura H et al. Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:906–909.

Lash RH, Genta RM, Schuler CM . Sessile serrated adenomas: Prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J Clin Pathol 2010;63:681–686.

Bettington M, Walker N, Rosty C et al. Clinicopathological and molecular features of sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia or carcinoma. Gut 2015;0:1–10.

Mitchell G Frequency matching. In: Armitage P, Colton T (eds) Encyclopedia of biostatistics. 2nd edn, Online John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, England, 2005.

Ban S, Mitomi H, Horiguchi H et al. Adenocarcinoma arising in small sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) of the colon: Clinicopathological study of eight lesions. Pathol Int 2014;64:123–132.

Yang JF, Tang SJ, Lash RH et al. Anatomic distribution of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without cytologic dysplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015;139:388–393.

Sheridan TB, Fenton H, Lewin MR et al. Sessile serrated adenomas with low- and high-grade dysplasia and early carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;126:564–571.

Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1315–1329.

Lu F, van Niekerk DW, Owen D et al. Longitudinal outcome study of sessile serrated adenomas of the colorectum: an increased risk for subsequent right-sided colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:927–934.

Kim KM, Lee EJ, Ha S et al. Molecular features of colorectal hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenoma/polyps from Korea. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:1274–1286.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Presented in part at the annual United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology meeting in 2016, Seattle, WA, USA.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cenaj, O., Gibson, J. & Odze, R. Clinicopathologic and outcome study of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with serrated versus intestinal dysplasia. Mod Pathol 31, 633–642 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.169

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.169

This article is cited by

-

Associations between molecular characteristics of colorectal serrated polyps and subsequent advanced colorectal neoplasia

Cancer Causes & Control (2020)

-

An update on the morphology and molecular pathology of serrated colorectal polyps and associated carcinomas

Modern Pathology (2019)

-

The association between colorectal sessile serrated adenomas/polyps and subsequent advanced colorectal neoplasia

Cancer Causes & Control (2019)