Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to assess parents’ interest in whole-genome sequencing for newborns.

Methods:

We conducted a survey of a nationally representative sample of 1,539 parents about their interest in whole-genome sequencing of newborns. Participants were randomly presented with one of two scenarios that differed in the venue of testing: one offered whole-genome sequencing through a state newborn screening program, whereas the other offered whole-genome sequencing in a pediatrician’s office.

Results:

Overall interest in having future newborns undergo whole-genome sequencing was generally high among parents. If whole-genome sequencing were offered through a state’s newborn-screening program, 74% of parents were either definitely or somewhat interested in utilizing this technology. If offered in a pediatrician’s office, 70% of parents were either definitely or somewhat interested. Parents in both groups most frequently identified test accuracy and the ability to prevent a child from developing a disease as “very important” in making a decision to have a newborn’s whole genome sequenced.

Conclusion:

These data may help health departments and children’s health-care providers anticipate parents’ level of interest in genomic screening for newborns. As whole-genome sequencing is integrated into clinical and public health services, these findings may inform the development of educational strategies and outreach messages for parents.

Genet Med 16 1, 78–84.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Newborn screening (NBS) is an undeniably successful program. In the 50 years since their inception, state-mandated NBS programs have saved thousands of children’s lives and prevented disabilities in countless more cases by early identification and treatment of children with inherited diseases.1 Although screening was performed for only a few conditions (e.g., phenylketonuria and congenital hypothyroidism) in the early years of the NBS program,2 the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children currently recommends that states screen for 31 disorders.3 This increase in screening is largely due to expansion spurred by advances in testing technologies—the most recent and dramatic example of which is tandem mass spectrometry —that allowed the testing process to become faster and scalable without a significant increase in incremental testing costs.4

The technological drive in NBS programs continues as we embrace the genomic era. States have begun to utilize genetic-based tests as an adjunct to traditional metabolic tests—usually for single-gene disorders such as cystic fibrosis.5 However, the increasing affordability of genetic sequencing technology has sparked new discussions about the incorporation of next-generation genetic sequencing into NBS programs.6,7 In December 2010, the National Institute for Child Health and Development sponsored a symposium to develop a research agenda around the “application of new genomics concepts and technologies to newborn screening and child health.”8 In addition, the National Institutes of Health recently published a request for proposals that will assess the potential value and challenges of integrating genomic sequencing into NBS programs.9

The integration of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing into state NBS programs may be appealing given the possibility of these technologies to improve the quality of screening, reduce costs, and open the potential to utilize the programs to screen children for a much wider range of conditions. However, although interest in the potential utilization of genomic sequencing in the newborn period is growing, the use of this technology raises a number of ethical, social, and practical issues for parents and providers. First, there are concerns about the potential psychosocial harms associated with unexpected genomic results (e.g., results for nonscreened conditions, including those with adult onset), as well as how to interpret complex or ambiguous results. There are also questions about whether parents should have access to all of their newborn’s genomic data. In addition, these complexities may have implications for the mandatory nature of NBS programs and amplify current debates about whether informed consent is needed for expanded screening.10 Finally, the use of WGS in the newborn period raises numerous practical challenges regarding the ability to manage and interpret the large amount of data generated through these testing platforms and then appropriately communicate that information to families and their primary-care providers.

The venues in which parents may be offered WGS may also raise unique challenges and have an impact on parental attitudes toward the uses of this technology. For example, when initiated within the context of a NBS program, parents may have significant concerns about the storage and potential uses of genomic data by a state government agency. Although a number of scholarly discussions have addressed the potential benefits and harms of using genomics within NBS,11,12,13 few empirical studies have examined parental interest and attitudes toward WGS in the newborn period—either within or outside of NBS programs. Therefore, we sought to assess parents’ interest in WGS of newborns as part of a state NBS program and to examine whether this interest may differ if sequencing were offered within the context of a pediatrician’s office.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A nationally representative sample of the US population was surveyed in May 2012 regarding their interest in WGS for themselves, the individual’s youngest child (when applicable), and a hypothetical future newborn. This survey was conducted as part of the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health, a recurring online survey of parents and nonparents that has served as a national sampling platform for several peer-reviewed studies of policy-relevant questions regarding children’s health.14,15,16 The data presented in this paper focus on results related to parental attitudes concerning the use of WGS in the newborn period. Data regarding attitudes toward WGS for participants themselves and their youngest children will be reported in a separate paper. The University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study population

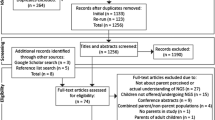

The National Poll on Children’s Health is conducted using GfK/Knowledge Networks Web-enabled KnowledgePanel, a nationally representative probability-based panel. Knowledge Networks uses a random selection of telephone numbers and residential addresses to identify and invite potential participants (using telephone or mail) to participate in the Web-enabled KnowledgePanel.17 Once enrolled in the panel, participants receive unique login information to access surveys online and receive e-mails throughout each month inviting them to participate in a variety of research studies. If contacted individuals have an interest in participating in the KnowledgePanel but do not have Internet access, Knowledge Networks provides them a laptop and internet connection free of cost.

Survey administration

The National Poll on Children’s Health that included the section on WGS was pilot tested in April 2012 with a separate convenience sample of 100 KnowledgePanel members. The introductory e-mail invited members to participate in a survey about child health. No additional incentive participation was offered beyond the usual panel participation points. To ensure adequate representation, parents (defined as individuals having children aged 0–17 years living in the household) and racial/ethnic minorities were oversampled.

Survey questions/outcomes

All survey respondents received this brief explanation of genes and health and WGS:

-

Staying healthy and getting sick are affected by many things. Our genes—which we inherit from our parents—can affect our health and illness in many ways.

-

Genes are made of DNA and contain the instructions needed for our bodies to grow and function. All of the genes in a person make up that person’s genome.

-

It is possible to study a person’s entire genome. This process is called whole genome sequencing. It may give information about a person’s risk of having different diseases in the future.

Participants were then asked about their interest in WGS for themselves, and when applicable, genomic sequencing for their youngest child. These results will be reported in a separate paper. Participants were then randomized into two groups, each receiving a different scenario regarding the offering of WGS for a hypothetical future newborn. One group received a scenario in which WGS was offered as part of their state’s NBS program (NBS), whereas the other group’s scenario included WGS for their future newborn in the context of a pediatrician’s office visit (pediatrician). Figure 1 contains the language used for the two scenarios. All participants were then asked how interested they would be in having their future newborn’s genome sequenced, using a Likert scale of responses (definitely interested/somewhat interested/not interested/definitely not interested). Participants were then shown a series of factors that might influence their interest in getting WGS for a newborn, such as accuracy of the testing and privacy of the test results. This list of factors was developed by the authors and was based on previous literature and their experience with studies regarding public attitudes toward genetic screening. The list was meant to represent potential positive and negative implications of WGS. Table 1 contains a list of all the factors presented to participants. Using a five-point scale, participants were asked to rate how important each factor would be in their decision to have their newborn’s whole genome sequenced.

Next, participants who received the NBS scenario were also asked a second question regarding their interest in WGS through their state but with the following text added:

Imagine that your state wants to store the information from your child’s whole genome sequence and use it for health-related research. Researchers would NOT be able to identify your child from the information.

Parents were then asked again to rate (using a four-point Likert scale) how interested they would be in having their newborn’s whole genome sequenced under these conditions.

In addition to these questions, we also collected the following information from respondents about themselves: age, sex, race, education, household income, political ideology, rating of personal health, and if they plan to have a child within 5 years (only asked if respondent was younger than 45 years). From parents, we also gathered the following information about their children: age, sex, and whether their children have any chronic health conditions.

Statistical analysis

Knowledge Networks provided the study team with deidentified data, along with census-based poststratification weights used to match the US population distribution on sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, census region, income, and political ideology. All analyses were conducted using these weighted data to account for any potential nonresponder bias. All results reflect weighted data unless otherwise indicated. All analyses were conducted with Stata 12 (Stata, College Station, TX). To find associations between respondent characteristics and interest level in WGS, we collapsed interest level in WGS to two outcomes, not interested versus at least somewhat interested, and tested categorical variables with a Rao and Scott corrected Pearson’s χ2 test18 and the continuous variable age with binary logistic regression. Respondent characteristics significant at P < 0.2 were included in a multivariate binary logistic regression to determine independent significance. Comparison of interest level in WGS between different scenarios (e.g., those definitely interested in the NBS scenario versus those definitely interested in the pediatrician office scenario) was tested with an adjusted Wald test.

Results

Survey participant characteristics

Overall parental response rate for this study was 55%. Of the 1,539 total respondents, the majority were white non-Hispanic (63%), female (56%), and had at least some college education (62%). The mean age of the survey participants was 39 years. Income and political ideology were evenly distributed across respondents. All respondents to the newborn WGS section of the National Poll on Children’s Health were parents of at least one child younger than 18 years. Among these parents, 21% reported that they were planning to have another child in the next 5 years. Table 2 contains demographic characteristics for all survey respondents.

Interest in WGS of newborns

Overall interest in having future newborns undergo WGS was generally high for participants presented with either of the randomized scenarios (NBS versus pediatrician). Among study participants presented with the option of adding WGS as part of a state’s NBS program, 36% were definitely interested; 38.3% were somewhat interested; 18% were not interested; and 8% were definitely not interested. Participants more likely to be interested in WGS through NBS were female (odds ratio (OR) = 1.77; P < 0.01), those with at least some college education versus less than high school (OR = 2.04; P = 0.02), those planning to have a child in the next 5 years versus not (OR = 2.22; P = 0.02), and participants whose youngest child has two or more health conditions (OR = 2.63; P < 0.01). Participants who self-identified as politically conservative had lower interest in WGS through NBS programs as compared with those who identified as politically moderate (OR = 0.58; P < 0.05).

Participants presented with the scenario in which WGS is offered in the context of a pediatric office visit were similarly interested, with 31% definitely interested; 39% somewhat interested; 22% not interested; and 8% definitely not interested. Female participants were more likely to be interested in WGS through a pediatrician (OR = 2.28; P < 0.001). In Figure 2 , we compare parental interest in WGS in the state NBS program and the pediatrician’s office scenarios. There were no statistically significant differences in parent’s interest in WGS between these two scenarios.

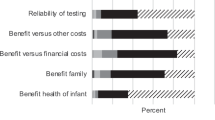

Factors impacting parental interest in newborn WGS

Parents in both the NBS and pediatrician’s office scenarios identified similar sets of factors as “very important” in making a decision to have a newborn baby’s whole genome sequenced ( Table 1 ). Overall, parents in both scenario groups most frequently identified “accuracy of the test” (NBS = 74%; pediatrician = 68%) and the potential for “preventing or decreasing a child’s chances of developing disease” (NBS = 67%; pediatrician = 66%) as “very important.” Alternatively, concern that WGS could reveal that their “child is at a higher risk of developing certain diseases than other people” was chosen as a “very important” factor by the lowest proportions of parents in both scenarios (NBS = 40%; pediatrician = 46%).

When stratified by level of interest in WGS, parents in both scenario groups who expressed a “definite interest” in WGS for a future newborn more frequently identified “accuracy of the test,” the ability to use the results in “choosing more effective medical treatments,” and potential for “preventing or decreasing a child’s chances of developing disease” as “very important” factors impacting their interest in WGS. Alternatively, parents who expressed no interest in newborn WGS most frequently identified concerns about the “privacy of the results,” “potential for results to be used to discriminate against their child,” and the potential that results could be used without their permission as “very important.” However, we are not able to make statistical inferences about these differences due to the small number of parents who expressed that they were “definitely not interested” in WGS.

Interest in WGS of newborns when data may be used for research

When parents in the NBS scenario group were presented with the possibility that the data obtained through WGS could be stored and used in subsequent deidentified research, participant’s interest remained generally high, with 25.1% definitely interested; 39.1% somewhat interested; 24% not interested; and 11.8% definitely not interested. However, the number of parents expressing a “definite interest” in WGS was significantly lower statistically as compared with parents’ interest when the potential storage and use of data were not mentioned (P < 0.001). Higher interest in WGS with the added possibility of research was evident among parents with a bachelor’s degree or higher as compared with those with a high school diploma or lower (OR = 1.81; P = 0.02), those expecting to have a child in the next 5 years versus not (OR = 1.95, P = 0.01), and participants whose youngest child has two or more health conditions (OR = 1.91; P = 0.03). Participants expressing a conservative political ideology again demonstrated lower interest in WGS than those who identify as politically moderate (OR = 0.64; P = 0.05).

Discussion

Parental interest in WGS

The results from our study suggest that, at baseline, parents have a substantial level of interest in WGS for their newborn. Moreover, parents’ interest did not differ based on whether the sequencing was offered as part of the NBS program or in their pediatrician’s office. In both the NBS and pediatrician’s office scenarios, more than 60% of participants were either definitely or somewhat interested in having a potential future newborn’s whole genome sequenced. These data suggest that the venues in which parents may be offered WGS may not strongly impact their interest in having screening done. However, it is important to note that as public health institutions or clinical providers make decisions on how best to implement WGS into practice, there may be issues regarding sample collection, data management, or disclosure of results that may inevitably influence parental attitudes regarding preferred testing venues. Nevertheless, these data also suggest that parents may not have significant reservations about a state-run public health program offering WGS for newborns as part of a larger goal of detecting early disease in newborns.

Storage and use of genomic data

Although interest in WGS offered as an option through a state’s NBS program was high, there was a drop in interest when parents were presented with the possibility that deidentified data generated from sequencing might be stored and used in future research. These data raise significant questions for states regarding the long-term management of the vast amounts of genetic data generated through NBS programs and who might have access to these data. These concerns are in part already being played out in recent debates over the research use of residual blood spots stored by programs after screening takes place.19 Currently, a number of states are involved in debates over the storage and use of their leftover NBS blood spots, and lawsuits have been recently filed in Minnesota and Texas over the storage and use of these samples.20,21 These debates have centered on long-standing discussions about the balance between the use of public health data for research and the rights of citizens from whom the data have been collected.22 Our findings suggest that parents’ level of comfort with the use of stored genomic information for research may impact their interest in utilizing WGS. Additional research is necessary to further explore the implications of storage and use of genomic data on parental attitudes toward WGS.

Factors impacting interest in WGS

In addition to assessing interest level among parents, our data also identify a number of expectations parents may have regarding the utility of newborn WGS as well as concerns about the management and protection of the data generated through sequencing. Overall, parents identified issues associated with the accuracy of the tests and the potential usefulness of the genomic risk data to help prevent disease as important factors that may influence their interest in WGS for their newborns. Alternatively, parental worries that the test may reveal that their child has a “higher risk of developing certain diseases than other people” was less frequently chosen as an influential factor when trying to decide whether or not to have a newborn’s genome sequenced. This may indicate that parents may be more likely to value the precision of the testing platforms and the clinical utility of the information more than concerns regarding disclosure of disease risk when making decisions about screening.

Although not statistically significant due to the small number of parents who indicated no interest in WGS, these data also raise questions about differences in what kinds of factors might influence parents who favor WGS as opposed to those who do not. The data presented here show some evidence that parents who have a high interest in WGS are concerned with factors associated with the quality and usefulness of the test, whereas parents who have no interest may be influenced by questions related more to the security and potential uses of genomic data. More research on these kinds of concerns is needed using a larger sample. These kinds of data could be useful in the development of educational materials and consent processes about WGS to better address differing parental expectations and concerns.

Limitations

This study has limitations that merit discussion. First, participants were asked to report their interest in WGS for a hypothetical future newborn. Therefore, these data may not reflect the decisions of a parents actually confronted with making a decision about WGS for their own new baby. However, given that WGS in newborns is currently rare, we believe that the use of a hypothetical scenario provides an important mechanism to assess parental attitudes before this technology becomes more common in clinical settings. In addition, we did see some differences between the attitudes of parents who intend to have a child in the next 5 years and those who do not. These differences may indicate that the use of a hypothetical scenario may help us to understand how parents who may be faced with making decisions about WGS or other types of genomic testing feel about these technologies. Second, we acknowledge that the limited introduction of WGS given to parents in this study may not provide them with the most robust information about the potential uses and limitations of this technology. However, we intended for this survey to provide a baseline for exploring parental attitudes about WGS in the newborn period within the context of what parents may currently know about genomic testing. It is meant to represent parental interest based on the kind of information that most parents may have before going through a more extensive educational discussion about the uses of this technology. Finally, our study design did not explore the motivations behind respondents’ interest levels or why certain respondent characteristics are associated with higher levels of interest in WGS. Further research is necessary to better explore these issues with parents.

Conclusion

Overall interest in having one’s future newborn’s genome sequenced was generally high for participants presented with either WGS scenario. This finding suggests that the potential distinction between offering WGS in the NBS setting or through other clinical venues may not be meaningful to parents. Nevertheless, programmatic choices within state health departments may impact parental attitudes, given that parents in our survey did have significantly lowered interest in WGS if the state had plans to keep sequencing data for future research.

In addition to personal relevance, these data may also suggest a generally high level of public acceptability for the utilization of these technologies in NBS and other clinical settings. However, we do not believe that these data support the promotion of the widespread offering of newborn WGS in either NBS or clinical practice. Rather, our findings may help providers and health departments better anticipate parents’ interest in these technologies as they become more available in clinical settings. Such data will also be crucial for health departments and other health-care providers to better understand which factors are important to parents in making a decision about whether or not to pursue WGS. This information will be helpful for developing programs to better educate families while also ensuring that parents have access to clinical resources for adequate pretest and posttest counseling about genetic test results.

Ultimately, parental interest must be contextualized within the larger set of ethical and programmatic concerns related to WGS in newborns. The initial set of data regarding parental interest presented here creates a starting place for further empirical inquiry into the potential social and ethical implications of integrating genomic sequencing into NBS programs. Addressing these issues requires thoughtful consideration of the values and perceptions of multiple stakeholders, including parents, providers, NBS program officials, genome scientists, and other stakeholders. Such assessment will help health departments and other health-care providers make more informed choices about when and how to utilize these technologies in the newborn period.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

National Newborn Screening and Genetics Resource Center. National newborn screening report. http://genes-rus.uthscsa.edu/resources/newborn/00/ch2_complete.pdf. Accessed 3 December 2012.

Paul DB . The history of newborn phenylketonuria screening in the U.S. In: Task Force on Genetic Testing (U.S.), Holtzman NA, Watson MS (eds). Promoting Safe and Effective Genetic Testing in the United States: Final Report of the Task Force on Genetic Testing. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, 1998:xxiv, 186 p.

Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children. Recommended Uniform Screening Panel of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children. http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/mchbadvisory/heritabledisorders/recommendedpanel/index.html. Accessed 7 December 2012.

Chace DH, Kalas TA, Naylor EW . Use of tandem mass spectrometry for multianalyte screening of dried blood specimens from newborns. Clin Chem 2003;49:1797–1817.

Comeau AM, Parad RB, Dorkin HL, et al. Population-based newborn screening for genetic disorders when multiple mutation DNA testing is incorporated: a cystic fibrosis newborn screening model demonstrating increased sensitivity but more carrier detections. Pediatrics 2004;113:1573–1581.

McCandless SE, Chandrasekar R, Linard S, Kikano S, Rice L . Sequencing from dried blood spots in infants with “false positive” newborn screen for MCAD deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2013;108:51–55.

Solomon BD, Pineda-Alvarez DE, Bear KA, Mullikin JC, Evans JP ; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Applying genomic analysis to newborn screening. Mol Syndromol 2012;3:59–67.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Newborn screening in the genomic era: setting a research agenda, 2011. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/meetings/2010/Pages/121410.aspx. Accessed 25 October 2012.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Genomic Sequencing and and Newborn Screening Disorders, 2012. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HD-13-010.html. Accessed 10 August 2012.

Ross LF, Saal HM, David KL, Anderson RR ; American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Technical report: ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Genet Med 2013;15:234–245.

Clayton EW . Currents in contemporary ethics. State run newborn screening in the genomic era, or how to avoid drowning when drinking from a fire hose. J Law Med Ethics 2010;38:697–700.

Goldenberg AJ, Sharp RR . The ethical hazards and programmatic challenges of genomic newborn screening. JAMA 2012;307:461–462.

Rothstein MA . Currents in contemporary bioethics. J Law Med Ethics 2012;40:682–689.

C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health. http://mottnpch.org/. Accessed 1 December 2012.

Tarini BA, Goldenberg A, Singer D, Clark SJ, Butchart A, Davis MM . Not without my permission: parents’ willingness to permit use of newborn screening samples for research. Public Health Genomics 2010;13: 125–130.

Tarini BA, Singer D, Clark SJ, Davis MM . Parents’ interest in predictive genetic testing for their children when a disease has no treatment. Pediatrics 2009;124:e432–e438.

Dennis JM . Summary of KnowledgePanel(R) Design, 2010. http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/reviewer-info.html. Accessed 2 December 2012.

Rao JNK, Scott AJ . On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency-tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Ann Stat 1984;12(1):46–60.

Therrell BL Jr, Hannon WH, Bailey DB Jr, et al. Committee report: considerations and recommendations for national guidance regarding the retention and use of residual dried blood spot specimens after newborn screening. Genet Med 2011;13:621–624.

Beleno v Texas Dept. of State Health Serv. Case 5:2009cv00188. U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas in San Antonio, 3 March 2009.

Bearder, et al v State of Minnesota, et al. Fourth Judicial Circuit, County of Hennepin District Court; 24 November 2009.

Tarini BA . Storage and use of residual newborn screening blood spots: a public policy emergency. Genet Med 2011;13:619–620.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health (NPCH), http://www.MottNPCH.org. Funding for the NPCH is provided by the University of Michigan Health System and the Department of Pediatrics and Communicable Diseases. A.J.G. was supported by the Center for Genetic Research Ethics and Law (2P50-HG-003390-06) from the National Human Genome Research Institute. B.A.T. was supported by the Clinical Sciences Scholars Program at the University of Michigan and a K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (K23HD057994). We thank Amy Butchart, Anna Daly Kaufmann, and Sarah Clark for their thoughtful review of questions and editorial suggestions during development of the survey, and Achamyeleh Gebremariam for providing consultation about the statistical analysis. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the University of Michigan or Case Western Reserve University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldenberg, A., Dodson, D., Davis, M. et al. Parents’ interest in whole-genome sequencing of newborns. Genet Med 16, 78–84 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.76

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.76

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Perception of genomic newborn screening among peripartum mothers

European Journal of Human Genetics (2024)

-

Genomic newborn screening for rare diseases

Nature Reviews Genetics (2023)

-

Expanding the Australian Newborn Blood Spot Screening Program using genomic sequencing: do we want it and are we ready?

European Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Attitudes towards genetic testing and information: does parenthood shape the views?

Journal of Community Genetics (2020)

-

Newborn screening for Pompe disease: impact on families

Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease (2018)