Abstract

Purpose:

Whether and how to return individual genetic results to study participants is among the most contentious policy issues in contemporary genomic research.

Methods:

We surveyed corresponding authors of genome-wide association studies, identified through the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies, to describe the experiences and attitudes of these stakeholders.

Results:

Of 357 corresponding authors, 200 (56%) responded. One hundred twenty-six (63%) had been responsible for primary data and sample collection, whereas 74 (37%) had performed secondary analyses. Only 7 (4%) had returned individual results within their index genome-wide association studies. Most (69%) believed that return of results to individual participants was warranted under at least some circumstances. Most respondents identified a desire to benefit participants’ health (63%) and respect for participants’ desire for information (57%) as major motivations for returning results. Most also identified uncertain clinical utility (76%), the possibility that participants will misunderstand results (74%), the potential for emotional harm (61%), the need to ensure access to trained clinicians (59%), and the potential for loss of confidentiality (51%) as major barriers to return of results.

Conclusion:

Investigators have limited experience returning individual results from genome-scale research, yet most are motivated to do so in at least some circumstances.

Genet Med 15 11, 882–887.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Through genome-wide association studies (GWASs), investigators have identified thousands of single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with a variety of diseases.1 Although most of these variants have modest relationship to disease risk, a subset of single-nucleotide polymorphisms correspond to available clinical tests.2 In this context, a discussion has emerged about the ethics of returning individual genetic results to research participants.3,4,5,6 Although participant preferences are not the only factor that should determine policies, data suggest that most participants desire results.7,8,9 Furthermore, guidelines support the return of nongenetic incidental findings, such as those encountered in neuroimaging research, at least when the findings have immediate clinical significance.10,11,12 Finally, although some commentators disagree,13,14,15 guidelines recommend that a limited set of individual genetic results with clear clinical validity and utility should be returned to participants who have indicated during the consent process that they desire to receive such results.4,16,17

Genome investigators are critical stakeholders in this debate. However, evidence about their attitudes and practices is limited.18,19 We therefore surveyed corresponding authors of published GWASs in order to describe their perspectives and experiences with returning individual genetic research results.

Materials and Methods

Survey instrument

We reviewed published work on the return of individual genetic results to research participants to develop a draft questionnaire. The draft survey consisted of four sections: demographics and work characteristics, study characteristics and roles, study practices, and views. When providing information about study characteristics, roles, and practices, respondents were directed to consider the particular study on the basis of which they were identified for this survey. The survey was revised following face validity assessment by two genetic/genomic epidemiology researchers who were not eligible for participation in the study (see Supplementary Data for the survey instrument).

Study population, recruitment, and survey administration

Eligible investigators were identified through the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies (accessed 15 April 2010).20 When an individual was corresponding author on more than one study, he or she was contacted with reference to the most recent publication. Data collection occurred between October 2010 and February 2011.

Investigators were contacted up to five times to participate in the survey. An initial and two follow-up invitations were sent via publicly available e-mail addresses with a link to the online survey. The online survey was administered using a Web-based survey self-administration system (Illume; DatStat, Seattle, WA). The penultimate contact included a letter and paper version of the survey sent via the US Postal Service or Federal Express to nonrespondents to the follow-up e-mails. The final contact to nonresponders was via e-mail with a link to the online survey.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Baylor College of Medicine.

Statistical analysis

Stata 10 (Stata, College Station, TX) was used to perform appropriate descriptive statistical analyses and hypothesis tests. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate associations between categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to assess the relationship between independent variables and ordinal outcome variables such as the degree to which respondents perceived various factors as barriers to or motivations for return of results. In all analyses, statistical significance was declared if two-sided P values were <0.05.

Results

Characteristics of respondents and of index GWASs

Of 360 unique corresponding authors eligible to take part in the survey, contact information was unavailable for three. Of the remaining 357, 200 responded (response rate: 56%; 191 responses were complete). Respondents’ demographic and professional characteristics are shown in Table 1 ; most were male and self-identified as white.

Among responding investigators, 62 (31%) had published their GWAS in Nature Genetics, 12 (6%) in the American Journal of Human Genetics, and 11 (6%) in PLoS Genetics. No other journal accounted for more than 5% of responses.

Respondents did not differ from nonrespondents by journal in which the index GWAS was published or by region of origin; other characteristics were unavailable for nonrespondents.

The characteristics of the index GWAS on the basis of which investigators were selected are shown in Table 2 . Almost two-thirds of respondents reported that their study included primary collection of data and specimens, whereas 37% reported conducting secondary analyses using data and specimens obtained from another investigator or from a repository. Among those conducting secondary analyses, most had signed a data use agreement with the original collectors or repository, and most agreements forbade efforts at reidentifying participants. Regardless of whether the studies involved primary data and specimen collection or secondary analyses, most maintained links between the data and specimens and the identities of the individual participants using a code.

Only seven respondents (4%) indicated that they had returned results to individual participants in the context of their index GWAS. Of the remaining respondents, only two (1%) had plans to do so. Of the nine investigators who had returned results or had plans to do so, all had been responsible for primary collection of data and samples; none had performed secondary analyses on data or samples collected by others. Most of those who had returned results (n = 5) did so directly to the participants or their proxies, rather than through the participant’s physician.

Investigators’ attitudes regarding return of results

Most respondents (n = 134; 69%) believed that the return of research results to individual GWAS participants was warranted under at least some circumstances. This belief was generally unassociated with demographic and professional characteristics. There were no significant associations between believing that individual genetic results should be returned in at least some circumstances and holding an MD degree (P = 0.48), having served on an IRB (P = 0.84), having interacted directly with participants (P = 0.31), or having been responsible for primary data or specimen collection (P = 0.79).

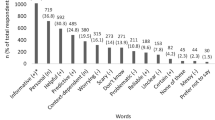

Respondents endorsed several factors as major motivations to return individual genetic research results (Figure 1). Most identified a desire to benefit participants’ health (63%) and respect for participants’ desire to have information about themselves (57%) as major motivations for returning individual results. Many (42%) also identified the belief that participants have a right to their data as a major motivation. However, respondents also reported a wide range of barriers to returning results ( Figure 2 ). Most viewed the uncertain clinical utility of genetic research results (76%), the possibility that participants will misunderstand the information they are given (74%), the potential for emotional harm to participants (61%), the need to ensure access to an appropriately trained clinician (59%), and the potential for loss of confidentiality (51%) as major barriers to the return of results.

We sought to understand which attitudes and concerns distinguished investigators who believed that individual genetic results should be returned in at least some circumstances from those who believed that results should generally not be returned. Investigators who believed that results should generally not be returned viewed the potential for loss of patient confidentiality (P = 0.004), the possibility that participants will misunderstand the information that they are given (P = 0.009), the potential for causing emotional harm to participants (P = 0.011), and the potential to blur the boundary between research and clinical care (P = 0.002) as greater barriers than those who believed that results should be returned under at least some circumstances. We also noted numerous differences between these two groups of investigators with respect to the motivations that they endorsed. Investigators who believed that results should be returned in some circumstances were more likely than those who did not share this belief to endorse the desire to benefit participants’ health (P = 0.003), respect for participants’ desires to have information about themselves (P = 0.002), the view that participants have a right to their data (P = 0.0002), concern over legal liability if individual results are not disclosed (P = 0.016), and gratitude to participants for taking part in the study (P = 0.0008) as motivations for offering to return results.

Investigators who had been responsible for primary collection of data and samples and those who had performed secondary analyses of data or samples collected by others endorsed different barriers to and motivations for returning results. Those who had performed secondary data analyses perceived the time commitment required to return results (P = 0.029), the need to keep contact information current (P = 0.054), and the need to use a clinically certified laboratory (P = 0.007) as greater barriers to the return of individual results. Those responsible for primary data collection, by contrast, viewed the desire to benefit participants’ health as a greater motivation to return results (P = 0.008).

Discussion

We surveyed corresponding authors of published GWASs to clarify their experiences with and attitudes toward return of individual results and incidental findings from genome-scale studies. Few respondents reported experience with returning individual results, at least within their index GWAS. This observation suggests that investigators may be unprepared for the challenges posed by whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing studies, which will identify clinically relevant incidental findings more frequently than do GWASs.21,22,23 In qualitative interviews, however, we observed that many genome investigators report having returned results identified through other study designs, including linkage and family studies.24 Although linkage and family designs differ in numerous ways from sequencing-based approaches, this experience may be helpful as investigators consider whether and how to return incidental findings uncovered by sequencing research.

Notwithstanding their lack of personal experience with returning results from genome-scale studies, most respondents reported believing that return of individual genetic research results may be warranted under at least some circumstances. Major motivations cited by respondents for returning results included a desire to benefit participants’ health and respect for participants’ desires for information about themselves. Major barriers included the uncertain clinical utility of results, the possibility that participants might misunderstand information, the potential for emotional harm, the need to ensure access to appropriately trained clinicians, and the potential for loss of confidentiality.

Respondents who believed that individual results should generally not be offered to research participants differed with respect to the motivations and barriers that they cited from those who believed that results should at least sometimes be offered. In particular, they were more likely to identify beneficence-based concerns such as loss of confidentiality, the possibility that participants would misunderstand the information, and the potential for emotional harm. Of note, respondents who believed that results should generally not be offered were not more likely than other respondents to identify logistical barriers to return, including the need to ensure access to a trained clinician, the need to use a clinically certified laboratory, the time and costs involved, or the need to keep contact information current.

Respondents who had been responsible for primary specimen and data collection identified different barriers and motivations as compared with those who had conducted secondary analyses of specimens and data collected by others. These differences may reflect closer interactions between investigators responsible for primary specimen and data collection and the participants in their studies, or may derive from these investigators’ greater ability to provide results through established contact pathways.

Few previous studies have addressed researchers’ perspectives on return of results. Among 19 GWAS investigators interviewed by Williams et al.,19 few had experience returning results. Investigators generally emphasized reasons not to return results but felt compelled to disclose “when research resulted in genomic incidental findings with clear or probable medical significance.” Meacham et al.18 presented 44 investigators who had received federal funding to conduct human subjects research, not limited to genomic research, with a hypothetical scenario involving identification of a genetic variant associated with a “high risk” of developing colorectal cancer. Most investigators said they would offer the results to participants and identified ensuring high-quality information, the need to minimize harm to participants, and adherence to IRB and other rules as their principal concerns in deciding about return. Our study supports the observations of this previous work while extending the findings to a large, representative, international sample of genome investigators.

Although we cannot directly compare the views of investigators reported here to those of other stakeholder groups, some generalizations are possible. In most previous studies of participants or members of the public, a higher proportion of respondents than we observed among investigators—generally 80–90%—indicate a desire for access to individual results.8 Participants are also more likely to enroll in studies when they have access to results.7 In qualitative studies, most IRB representatives also indicate support for return of results with definite clinical utility while expressing concern about the possibility of returning unvalidated results.19,25 Our data suggest that most investigators share with IRB representatives both a willingness to return results in select circumstances and a recognition of the numerous concerns and caveats surrounding the move toward offering results.

This study has limitations. First, the experiences and attitudes of nonrespondents may differ from those of survey respondents. Although respondents and nonrespondents were similar with respect to region of origin and journal in which their index GWAS was published, we lacked other data on nonrespondents and therefore could not comprehensively compare the characteristics of respondents with those of nonrespondents. Second, the issues addressed in this survey are complex, and the survey questions may not have fully captured investigators’ perspectives. Follow-up qualitative interviews, reported separately, provide additional insights into the views of genome investigators regarding return of results.24

In conclusion, investigators have limited experience returning individual results identified in the course of genome-scale research, yet most are motivated to do so in at least some circumstances. Given the rapid transition of research from genotyping of common variants to sequencing for rare, potentially highly penetrant variants, and in light of policy guidance suggesting that offering results is sometimes ethically required,4,16,17,26 the need to develop mechanisms to facilitate the return of results has become urgent. To be successful, such mechanisms must address the concerns identified by the genome researchers who will be responsible for implementing them in practice.

Disclosure

R.B.R. reports that she has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. A.L.M. and S.E.P. report that they have received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas. S.J. reports that he receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Greenwall Foundation, that he was a paid member of a data-monitoring committee for Genzyme/Sanofi, and that he is an expert witness for counsel representing Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. J.O.R. and D.S.M. have no financial relationships to report.

References

Johnson AD, O’Donnell CJ . An open access database of genome-wide association results. BMC Med Genet 2009;10:6.

Johnson AD, Bhimavarapu A, Benjamin EJ, et al. CLIA-tested genetic variants on commercial SNP arrays: potential for incidental findings in genome-wide association studies. Genet Med 2010;12:355–363.

Bredenoord AL, Kroes HY, Cuppen E, Parker M, van Delden JJ . Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet 2011;27:41–47.

Fabsitz RR, McGuire A, Sharp RR, et al. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: updated guidelines From a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2010;3(6):574–580.

Meltzer LA . Undesirable implications of disclosing individual genetic results to research participants. Am J Bioeth 2006;6:28–30; author reply W10.

Bredenoord AL, Onland-Moret NC, Van Delden JJ . Feedback of individual genetic results to research participants: in favor of a qualified disclosure policy. Hum Mutat 2011;32:861–867.

Kaufman D, Murphy J, Scott J, Hudson K . Subjects matter: a survey of public opinions about a large genetic cohort study. Genet Med 2008;10:831–839.

Shalowitz DI, Miller FG . Communicating the results of clinical research to participants: attitudes, practices, and future directions. PLoS Med 2008;5:e91.

Richards MP, Ponder M, Pharoah P, Everest S, Mackay J . Issues of consent and feedback in a genetic epidemiological study of women with breast cancer. J Med Ethics 2003;29:93–96.

Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics 2008;36(2):219–248, 211.

Illes J, Kirschen MP, Edwards E, et al.; Working Group on Incidental Findings in Brain Imaging Research. Ethics. Incidental findings in brain imaging research. Science 2006;311:783–784.

National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. NIBIB Points to Consider for Investigators: Incidental Findings in Imaging Research, 2011; http://www.nibib.nih.gov/Research/Resources/PointsToConsider. Accessed 22 February 2013.

Bledsoe MJ, Clayton EW, McGuire AL, Grizzle WE, O’Rourke PP, Zeps N . Return of research results from genomic biobanks: cost matters. Genet Med 2013;15:103–105.

Ossorio P . Taking aims seriously: repository research and limits on the duty to return individual research findings. Genet Med 2012;14:461–466.

Beskow LM, Burke W . Offering individual genetic research results: context matters. Sci Transl Med 2010;2(38):38cm20.

National Bioethics Advisory Commission. Research Involving Human Biological Materials: Ethical Issues and Policy Guidance. National Bioethics Advisory Commission: Rockville, MD, 1999.

Beskow LM, Burke W, Merz JF, et al. Informed consent for population-based research involving genetics. JAMA 2001;286:2315–2321.

Meacham MC, Starks H, Burke W, Edwards K . Researcher perspectives on disclosure of incidental findings in genetic research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2010;5:31–41.

Williams JK, Daack-Hirsch S, Driessnack M, et al. Researcher and institutional review board chair perspectives on incidental findings in genomic research. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2012;16:508–513.

Hindorff LA, Junkins HA, Manolio TA . A catalog of published genome-wide association studies. http://www.genome.gov/26525384. Accessed 22 February 2013.

Kohane IS, Hsing M, Kong SW . Taxonomizing, sizing, and overcoming the incidentalome. Genet Med 2012;14:399–404.

Johnston JJ, Rubinstein WS, Facio FM, et al. Secondary variants in individuals undergoing exome sequencing: screening of 572 individuals identifies high-penetrance mutations in cancer-susceptibility genes. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:97–108.

Cassa CA, Savage SK, Taylor PL, Green RC, McGuire AL, Mandl KD . Disclosing pathogenic genetic variants to research participants: quantifying an emerging ethical responsibility. Genome Res 2012;22:421–428.

McGuire AL, Robinson JO, Ramoni RB, Morley DS, Joffe S, Plon SE . Returning genetic research results: study type matters. Per Med 2013;10:27–34.

Dressler LG, Smolek S, Ponsaran R, et al.; GRRIP Consortium. IRB perspectives on the return of individual results from genomic research. Genet Med 2012;14:215–222.

Knoppers BM, Joly Y, Simard J, Durocher F . The emergence of an ethical duty to disclose genetic research results: international perspectives. Eur J Hum Genet 2006;14:1170–1178.

Acknowledgements

The work of R.B.R. on this study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (K08DE016956). A.L.M., S.E.P., and J.O.R. acknowledge research support from the Baylor College of Medicine Clinical and Translational Research Program and the Baylor Annual Fund. S.E.P. acknowledges a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01HG006485-01). The investigators also acknowledge the Survey and Data Management Core at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for assistance with fielding the investigator survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data

(PDF 310 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramoni, R., McGuire, A., Robinson, J. et al. Experiences and attitudes of genome investigators regarding return of individual genetic test results. Genet Med 15, 882–887 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.58

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.58

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

To disclose, or not to disclose? Perspectives of clinical genomics professionals toward returning incidental findings from genomic research

BMC Medical Ethics (2021)

-

Return of genetic and genomic research findings: experience of a pediatric biorepository

BMC Medical Genomics (2019)

-

Improved ethical guidance for the return of results from psychiatric genomics research

Molecular Psychiatry (2018)

-

Return of individual genomic research results: what do consent forms tell participants?

European Journal of Human Genetics (2016)

-

Attitudes of nearly 7000 health professionals, genomic researchers and publics toward the return of incidental results from sequencing research

European Journal of Human Genetics (2016)