Abstract

The hereditary ataxias are a highly heterogeneous group of disorders phenotypically characterized by gait ataxia, incoordination of eye movements, speech, and hand movements, and usually associated with atrophy of the cerebellum. There are more than 35 autosomal dominant types frequently termed spinocerebellar ataxia and typically having adult onset. The most common subtypes are spinocerebellar ataxia 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7, all of which are nucleotide repeat expansion disorders. Autosomal recessive ataxias usually have onset in childhood; the most common subtypes are Friedreich, ataxia-telangiectasia, ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 1, and ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2. Four autosomal recessive types have dietary or biochemical treatment modalities (ataxia with vitamin E deficiency, cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, Refsum, and coenzyme Q10 deficiency), whereas there are no specific treatments for other ataxias. Diagnostic genetic testing is complicated because of the large number of relatively uncommon subtypes with extensive phenotypic overlap. However, the best testing strategy is based on assessing relative frequencies, ethnic predilections, and recognition of associated phenotypic features such as seizures, visual loss, or associated movement abnormalities.

Genet Med 15 9, 673–683.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hereditary Ataxia

The hereditary ataxias are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by slowly progressive incoordination of gait and often associated with poor coordination of hands, speech, and eye movements. Frequently, atrophy of the cerebellum occurs ( Figure 1 ). In this review, the hereditary ataxias are categorized by mode of inheritance and gene in which causative mutations occur, or chromosomal locus. The hereditary ataxias can be inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked manner or through maternal inheritance if part of a mitochondrial genetic syndrome. The genetic forms of ataxia are diagnosed by family history, physical examination, neuroimaging, and molecular genetic testing. The clinical manifestations may result from one or a combination of dysfunction of the cerebellar systems, lesions in the spinal cord, and peripheral sensory loss.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of the hereditary ataxias are progressive incoordination of movement and speech, and a wide-based, uncoordinated, unsteady gait. In addition, patients may develop ophthalmoplegia (limitations of eye movement), spasticity, neuropathy, and cognitive/behavioral difficulties. Particular signs beyond ataxia may guide the clinician in pursuit of directed genetic testing when investigating the cause of ataxia. For instance, cone–rod retinal dystrophy in conjunction with familial ataxia may suggest spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA)7; Native American origin or co-occurrence of epilepsy would raise the possibility of SCA10.

Establishing the diagnosis

Establishing the diagnosis of hereditary ataxia requires:

-

1

Detection on neurological examination of typical clinical signs including poorly coordinated gait and finger/hand movements, dysarthria (incoordination of speech), and eye movement abnormalities such as nystagmus, abnormal saccade movements, and ophthalmoplegia.

-

2

Exclusion of nongenetic causes of ataxia (see Differential Diagnosis below).

-

3

Documentation of the hereditary nature of the disease by finding a positive family history of ataxia, identifying an ataxia-causing mutation, or recognizing a clinical phenotype characteristic of a genetic form of ataxia.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of hereditary ataxia includes acquired, nongenetic causes of ataxia, such as alcoholism, vitamin deficiencies, multiple sclerosis, vascular disease, primary or metastatic tumors, and paraneoplastic diseases associated with occult carcinoma of the ovary, breast, or lung, and the idiopathic degenerative disease multiple system atrophy (spinal muscular atrophy). The possibility of an acquired cause of ataxia needs to be considered in each individual with ataxia because a specific treatment may be available.

Types of Hereditary Ataxia

As discussed above, the hereditary ataxias can be subdivided by mode of inheritance, (i.e., autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, and mitochondrial), gene in which causative mutations occur, or chromosomal locus.1,2,3

Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias

Synonyms for autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias (ADCAs) used prior to the identification of the molecular genetic basis of these disorders were Marie’s ataxia, inherited olivopontocerebellar atrophy, cerebello-olivary atrophy, or the more generic term, spinocerebellar degeneration.

Clinical features of ADCA. The age of onset and physical findings in the autosomal dominant ataxias overlap. Table 1 indicates a few distinguishing clinical features for each type.4,5,6,7,8 Scales for rating symptoms and signs of ataxia have been published.9 Often the autosomal dominant ataxias cannot be differentiated by clinical or neuroimaging studies; they are usually slowly progressive and often associated with cerebellar atrophy, as seen from brain imaging studies ( Figure 1 ). The frequency of the occurrence of each disease within the autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (ADCA) population is noted in Table 1 . Pyramidal signs (hyperreflexia and spasticity) are commonly found in patients with SCA1 and SCA3; cognitive impairment has been reported in association with SCA2, SCA12, SCA13, SCA17; chorea may manifest in patients with SCA17 or dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Many of the ADCAs in addition to limb and truncal ataxia cause dysarthria, dysphagia, and neuropathy. The clinical syndrome associated with SCA2 may include parkinsonism or motor neuron disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis)10,11 Age of onset is quite variable and usually in adulthood. Disease course is also variable, although generally the disease progresses over decades. Life span may be shortened in SCA1, -2, -3, and -7 or normal in SCA5, -6, and -14.5 The most common form of episodic ataxia is EA2, caused by a variety of point mutations in the same calcium channel gene (CACNA1A) associated with SCA6 and familial hemiplegic migraine.12

Genetics. The ADCAs for which specific genetic information is available are summarized in Table 1 . Most are SCAs; one is a complex form with additional phenotypic features in addition to ataxia; four are episodic ataxias; and one is a spastic ataxia. In addition to ADCAs described in Table 1 , ADCAs include:

-

1

Ataxia with early sensory/motor neuropathy (linked to 7q22–q32); caused by mutations in IFRD1.13,14

-

2

Cerebellar ataxia, deafness, narcolepsy, and optic atrophy (linked to 6p21–p23 in one family).15

-

3

Ataxia, cerebellar atrophy, intellectual disability, and possible attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (associated with a heterozygous mutation in SCN8A, encoding a sodium channel).16

-

4

Late-onset (40s–60s) cerebellar ataxia preceded by many years of spasmodic coughing. One individual had calcification of the dentate nuclei on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).17

Molecular genetic testing. Mutations associated with the ADCAs include nucleotide expansions occurring in either expressed or nonexpression regions of the gene, point mutations, duplications, and deletions.

Some of the earliest identified and most common ADCAs result from CAG trinucleotide expansions. SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA12, SCA17, and DRPLA are all caused by CAG repeats within the coding region of the respective genes translating into an elongated polyglutamine tract in the protein. Molecular genetic testing for CAG repeat length is a highly specific and sensitive diagnostic test. The sizes of the normal CAG repeat allele and of the full-penetrance disease-causing CAG expansion vary among the disorders (for individual reviews of each disorder see GeneReviews.org).

Although ordering molecular testing for the polyglutamine ataxia disorders listed above is straightforward and tests are commercially available, there are two notes of caution in the interpretation of results:

-

1

Some disorders are associated with alleles for which overlap exists between the upper range of normal and the lower range of abnormal CAG repeat size. Typically, such alleles are categorized as mutable normal or reduced penetrance. Mutable normal alleles (previously referred to as intermediate alleles) do not cause disease in the individual but can expand on transmission to a reduced or fully penetrant allele. Therefore, children of an individual carrying a mutable normal allele are at increased risk of inheriting a disease-causing allele. In addition, there are reduced-penetrance alleles that may or may not cause the disease in an individual; the probability of disease in persons with such alleles is typically unknown. Interpretation of test results in which the CAG repeat length is at the interface between the allele categories mutable normal/reduced penetrance and reduced penetrance/disease-causing can be difficult. In such cases, a consultation with the testing laboratory may be helpful to determine the precision of the CAG repeat length measurement.

-

2

In some instances, SCA2, SCA7, SCA8, and SCA10 result from extremely large CAG expansions in length that may be detected only by Southern blot analysis. For these disorders, a test result of apparent homozygosity (detection of a single allele by PCR analysis) must be interpreted in the context of multiple factors including clinical findings, family history, and age of onset of symptoms to determine whether Southern blot analysis to test for the presence of a large CAG expansion mutation is appropriate.

Other repeat expansions. SCA8 has a CTG trinucleotide repeat expansion in ATXN8OS.18 Extremely large repeats (~800) in ATXN8OS may be associated with an absence of clinical symptoms.19 The pathogenesis of the SCA8 phenotype is complex and also involves a (CAG)n repeat in a second overlapping gene, ATXN8.

SCA10 has a large expansion of an ATTCT pentanucleotide repeat in ATXN10, with the abnormal expansion range being much larger than that seen in the CAG repeat disorders.20

Anticipation. Anticipation is observed in the autosomal dominant ataxias in which CAG trinucleotide repeats occur. Anticipation refers to earlier onset of an increasing severity of disease in subsequent generations of a family. In the trinucleotide repeat diseases, anticipation results from expansion in the number of CAG repeats that occurs with transmission of the gene to the next generation. ATN1 (DRPLA) and ATXN7 (SCA7) have particularly unstable CAG repeats.21 In SCA7, anticipation may be so extreme that children with early-onset, severe disease die of the disorder long before the affected parent or grandparent is symptomatic.

Anticipation is a significant issue in the genetic counseling of asymptomatic at-risk family members and in prenatal testing. Although general correlations exist between earlier age of onset and more severe disease with increasing number of CAG repeats, the age of onset, severity of disease, specific symptoms, and rate of disease progression are variable and cannot be accurately predicted by the family history or molecular genetic testing. Attention has been focused on the phenomena of anticipation and trinucleotide repeat expansion, but it is important to note that the number of trinucleotide repeats can also remain stable or even contract on transmission to subsequent generations.

In the CAG repeat disorders, expansion of the repeat is more likely to occur with paternal than with maternal transmission of the expanded allele. By contrast, in SCA8, the majority of expansions of the CTG repeat occur during maternal transmission.

Prevalence. The prevalence of these rare diseases is not widely known. The prevalence of the ADCAs in the Netherlands is estimated to be at least 3:100,000.22 The prevalence of individual subtypes of ADCA may vary from region to region, frequently because of founder effects. For example, DRPLA is more common in Japan and SCA3 in Portugal; SCA2 is common in Korea and SCA3 is much more common in Japan and Germany than in the United Kingdom.23,24,25 SCA3 was originally described in Portuguese families from the Azores and called Machado-Joseph disease. DRPLA is rare in North America and common in Japan. A recent study found evidence of frequency variation between different regions in Japan.26 Data are based on a comprehensive study in the United States by Moseley et al.27

Autosomal recessive hereditary ataxias

Numerous recent reviews have detailed the clinical findings, genetics, and pathogenesis of the autosomal recessive ataxias.28 The autosomal recessive ataxias may present with additional extra–central nervous system signs and symptoms. Table 2 summarizes information for 13 typical autosomal recessive disorders in which ataxia is a prominent feature. The disorders are selected to indicate the range of genetic understanding that currently exists regarding recessive causes of ataxia.

Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) is the most common autosomal recessive ataxia, with a population frequency of 1–2:50,000. FRDA is characterized by slowly progressive ataxia with onset usually before 25 years of age and is typically associated with depressed tendon reflexes, dysarthria, Babinski responses, and loss of position and vibration senses.29 About 25% of affected individuals have an “atypical” presentation with later onset (age >25 years), retained tendon reflexes, or unusually slow progression of disease. The vast majority of individuals have a GAA triplet-repeat expansion in FXN. Unlike the ADCAs caused by CAG trinucleotide repeats, FRDA is not associated with anticipation.

Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) is characterized by progressive cerebellar ataxia beginning between 1 and 4 years of age, oculomotor apraxia, frequent infections, choreoathetosis, telangiectasias of the conjunctivae, immunodeficiency, and an increased risk for malignancy, particularly leukemia and lymphoma. Testing that supports the diagnosis of individuals with A-T is identification of a 7;14 chromosome translocation on routine karyotype of peripheral blood, the presence of immunodeficiency and elevated serum α-fetoprotein, and in vitro radiosensitivity assay. Molecular genetic testing of A-T is available clinically.

Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED) generally manifests in late childhood or early teens with dysarthria, poor balance when walking (especially in the dark), and progressive clumsiness resulting from early loss of proprioception. Some individuals experience dystonia, psychotic episodes (paranoia), pigmentary retinopathy, and/or intellectual decline. Most individuals become wheelchair bound as a result of ataxia and/or leg weakness between the ages 11 and 50 years. Although phenotypically similar to FRDA, AVED is more likely to be associated with head titubation or dystonia, and less likely to be associated with cardiomyopathy. It is important to consider the diagnosis of AVED (which can be made by measuring serum concentration of vitamin E) because it is treatable with vitamin E supplementation.30,31

A different autosomal recessive ataxia occurring on Grand Cayman Island is caused by mutations in ATCAY, the gene encoding the protein CRAL-TRIO, which may also be involved in vitamin E metabolism.32

Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 1 (AOA1) is characterized by childhood onset of slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia (mean onset age ~7 years), followed in a few years by oculomotor apraxia that progresses to external ophthalmoplegia. All affected individuals have a severe primary motor peripheral neuropathy leading to quadriplegia with loss of ambulation about 7–10 years after onset. Intellect remains normal in affected individuals of Portuguese ancestry, but mental deterioration has been seen in affected individuals of Japanese ancestry. The diagnosis of AOA1 is based on clinical findings and confirmed by molecular genetic testing.33,34,35

Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2 (AOA2) is characterized by onset between ages 10 and 22 years, cerebellar atrophy, axonal sensorimotor neuropathy, oculomotor apraxia, and elevated serum concentration of α-fetoprotein.36,37 The diagnosis of AOA2 is based on clinical and biochemical findings, family history, and exclusion of the diagnoses of A-T and AOA1; it is confirmed by molecular genetic testing.

Infantile-onset SCA is a rare disorder reported in Finland with degeneration of the cerebellum, spinal cord, and brain stem, and sensory axonal neuropathy.38

Marinesco–Sjögren syndrome is a rare disorder in which ataxia is associated with intellectual disability, cataract, short stature, and hypotonia.39,40

Polymerase γ-1-associated hereditary ataxias. Mutations in mitochondrial genes can result in an ataxia phenotype (see below). In addition, nuclear genes regulating mitochondrial processes can also result in a hereditary ataxia. Autosomal recessive mutations in polymerase γ-1 are associated with a broad spectrum of central nervous system and systemic phenotypes, but two in particular manifest with ataxia as a prominent feature.

-

Mitochondrial recessive ataxic syndrome: This is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in polymerase γ-1 and is characterized by cerebellar ataxia, nystagmus, dysarthria ophthalmoplegia, and frequently epilepsy; it is relatively common in Scandinavia. Age of onset ranges from childhood to mid-adulthood. Brain MRI may reveal cerebellar atrophy.41

-

Sensory ataxia, neuropathy, dysarthria, and ophthalmoplegia: As the name implies, a sensory neuropathy contributes to the ataxia observed in patients with sensory ataxia, neuropathy, dysarthria, and ophthalmoplegia. In addition, affected individuals may have eye movement abnormalities (ophthalmoplegia) and dysarthria.42 Epilepsy, myopathy, MRI abnormalities, and ragged red fibers have all been reported in association with sensory ataxia, neuropathy, dysarthria, and ophthalmoplegia.

Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay is characterized by early onset (age 12–18 months) difficulty in walking and gait unsteadiness. Ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity, extensor plantar reflexes, distal muscle wasting, a distal sensorimotor neuropathy predominantly in the legs, and horizontal gaze nystagmus constitute the major neurologic signs, which are most often progressive. Yellow streaks of hypermyelinated fibers radiate from the edges of the optic fundi in the retina of Quebec-born individuals with autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay,43 whereas the retinal changes are uncommon in French, Tunisian, and Turkish individuals with the condition.44,45 Individuals with autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay become wheelchair bound at the average age of 41 years; cognitive skills are preserved long term, and individuals are able to accomplish activities of daily living late into adulthood. Death commonly occurs in the sixth decade.

Refsum disease generally presents in childhood or young adulthood; in addition to ataxia, there may be peripheral neuropathy, deafness, ichthyosis, or retinitis pigmentosa.46

Polyneuropathy, hearing loss, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa, and cataract (PHARC), a syndrome similar to Refsum disease, is caused by mutations in ABHD12.47

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency is often associated with seizures, cognitive decline, pyramidal track signs, and myopathy but may also include prominent cerebellar ataxia.48,49 The symptoms may respond to CoQ10 treatment.

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis has characteristic thickening of tendons often associated with cognitive decline, dystonia, cataract, and white matter changes on brain MRI.

Other autosomal recessive ataxias

-

1

Members of a family from Saudi Arabia have cerebellar atrophy, ataxia, and axonal sensorimotor neuropathy (linked to chromosome 14q31–q32; associated with mutations in TDP1, encoding a topoisomerase 1-dependent DNA damage repair enzyme, SCAN1).50,51

-

2

Ataxia with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. A similar sibship has shown a deficiency of CoQ10.52

-

3

A single Slovenian family in which 5 of 14 siblings have ataxia with saccadic intrusions, sensory neuropathy, and myoclonus.53

-

4

A large consanguineous Norwegian family with infantile-onset nonprogressive ataxia (linked to 20q11–q13).54

-

5

A large consanguineous Saudi Arabian family has childhood-onset ataxia sometimes associated with epilepsy and cognitive deficits with a frameshift mutation in K1AA0226, which encodes rundataxin.55

-

6

Mutations in VLDLR, encoding the very low-density lipoprotein receptor, in Hutterite families with nonprogressive cerebellar ataxia and intellectual disability with inferior cerebellar hypoplasia and mild cerebral gyral simplification.56

-

7

Several French Canadian families in the Beauce region of Quebec with a late-onset cerebellar ataxia associated with mutations in SYNE1.57,58

-

8

Disorders associated with congenital cerebellar agenesis or hypoplasia of varying degrees:

-

Cerebellar agenesis with neonatal diabetes mellitus.61

-

Very low-density lipoprotein receptor–associated cerebellar hypoplasia.

-

Congenital disorders of glycosylation.62

-

1

Doi et al. (2011)65 have reported a single consanguineous Japanese sibship with childhood-onset psychomotor retardation followed by adult-onset gait ataxia associated with cerebellar vermis atrophy on MRI and a homozygous missense mutation in SYT14, the gene encoding synaptotagmin-14.

X-linked hereditary ataxias

X-linked sideroblastic anemia and ataxia are characterized by early-onset ataxia, dysmetria, and dysdiadochokinesis. The ataxia is either nonprogressive or slowly progressive. Upper motor neuron signs (brisk deep tendon reflexes, unsustained ankle clonus, and equivocal or extensor plantar responses) are present in some males. Mild learning disability is seen. Anemia is mild without symptoms. Carrier females have a normal neurologic examination. Causative mutations are present in ABC7, encoding a protein involved with mitochondrial iron transport, suggesting a common pathogenesis with FRDA.66

Adult-onset ataxia, especially in men, may be part of the fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome.67,68

Ataxias with mitochondrial gene mutations

A progressive ataxia is sometimes associated with mitochondrial disorders including myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers; neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa;1 and Kearns–Sayre syndrome. Mitochondrial disorders are often associated with additional clinical manifestations, such as seizures, deafness, diabetes mellitus, cardiomyopathy, retinopathy, and short stature.69 Pfeffer et al.70 report that missense mutations in MTATP6 can cause both childhood- and adult-onset cerebellar ataxia sometimes associated with abnormal eye movements, dysarthria, weakness, axonal neuropathy, and hyperreflexia.

Evaluation Strategy

Once a hereditary ataxia is considered in an individual, the following approach can be used to determine the specific cause to aid in discussions of prognosis and genetic counseling. Establishing the specific cause of hereditary ataxia for a given individual usually involves a medical history, physical examination, neurologic examination, neuroimaging, detailed family history, and molecular genetic testing.

Because of extensive clinical overlap among all of the forms of hereditary ataxia, it is difficult in any given individual with ataxia and a family history consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance to establish a diagnosis without molecular genetic testing. Clinical findings may help distinguish among some of the autosomal recessive ataxias.

A three-generation family history with attention to other relatives with neurologic signs and symptoms should be obtained. Documentation of relevant findings in relatives can be accomplished either through direct examination of those individuals or review of their medical records, including the results of molecular genetic testing, neuroimaging studies, and autopsy examinations.

NonDNA testing. Plasma clinical tests are available that suggest the presence of five autosomal recessive hereditary ataxias: elevated α-fetoprotein in A-T and AOA2, low serum vitamin E in AVED, elevated cholestenol in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, and hypoalbuminemia in AOA1. Normal values of these tests may sometimes represent false negatives and do not exclude a specific type of ataxia.

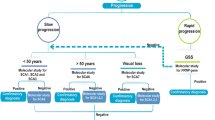

Testing strategy when family history suggests autosomal dominant inheritance. There has been much progress in our ability to identify causative genes for a significant proportion of autosomal dominantly inherited ataxias. An estimated 50–60% of the dominant hereditary ataxias (see Table 1 ) can be identified with highly accurate and specific molecular genetic testing for SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA8, SCA10, SCA12, SCA17, and DRPLA; all have nucleotide repeat expansions in the pertinent genes. Of note, the interpretation of test results can be complex because (i) the exact range for the abnormal repeat expansion has not been fully established for many of these disorders; and (ii) only a few families have been reported with SCA8 and thus penetrance and gender effects have not been completely resolved.71 Thus, diagnosis and genetic counseling of individuals undergoing such testing require the support of an experienced laboratory, medical geneticist, and genetic counselor.

Because of the broad clinical overlap, most laboratories that test for the hereditary ataxias have a battery of tests including testing for SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA7, SCA10, SCA12, SCA14, and SCA17. Many laboratories offer them as two groups in stepwise fashion based on population frequency, testing first for the more common ataxias, SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, and SCA7. Although pursuing multiple genes simultaneously may seem less optimal than serial genetic testing, it is important to recognize that the cost of the battery of ataxia tests often is equivalent to that of an MRI. Positive results from the molecular genetic testing are more specific than MRI findings in the hereditary ataxias. Guidelines for genetic testing of hereditary ataxia have been published.72

Testing is also available for some autosomal dominant forms of SCA that are not associated with repeat expansions, namely SCA5, SCA13, SCA14, SCA15, SCA27, SCA28, and 16q22-linked SCA.

Testing for the less common hereditary ataxias should be individualized and may depend on factors such as ethnic background (SCA3 in the Portuguese, SCA10 in the Native American population with some exceptions73); seizures (SCA10); presence of tremor (SCA12, fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome); presence of psychiatric disease or chorea (SCA17); or uncomplicated ataxia with long duration (SCA6, SCA8, and SCA14). Dysphonia and palatal myoclonus are associated with calcification of the dentate nucleus of cerebellum (SCA20).

If a strong clinical indication of a specific diagnosis exists based on the affected individual’s examination (e.g., the presence of retinopathy, which suggests SCA7) or if family history is positive for a known type, testing can be performed for a single disease.

Testing strategy when the family history suggests autosomal recessive inheritance. A family history in which only sibs are affected and/or when the parents are consanguineous suggests autosomal recessive inheritance. Because of their frequency and/or treatment potential, FRDA, A-T, AOA1, AOA2, AVED, and metabolic or lipid storage disorders such as Refsum disease and mitochondrial diseases should be considered.

Testing simplex cases. A simplex case is a single occurrence of a disorder in a family, sometimes incorrectly referred to as a “sporadic” case. If no acquired cause of the ataxia is identified, the probability is ~13% that the affected individual has SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, SCA8, SCA17, or FRDA,74 and mutations in rare ataxia genes are even less common.75 Other possibilities to consider are a de novo mutation in a different autosomal dominant ataxia, decreased penetrance, alternative paternity, or a single occurrence of an autosomal recessive or X-linked disorder in a family such as fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Although the probability of a positive result from molecular genetic testing is low in an individual with ataxia who has no family history of ataxia, such testing is usually justified to establish a specific diagnosis for the individual’s medical evaluation and for genetic counseling. Always consider a possible nongenetic cause such as multiple system atrophy, cerebellar type in simplex cases.76

Genetic Counseling

Risk to family members: autosomal dominant hereditary ataxia

Most individuals diagnosed as having autosomal dominant ataxia have an affected parent, although occasionally the family history is negative. For instance, family history may not be obvious because of early death of a parent, failure to recognize autosomal dominant ataxia in family members, late onset in a parent, reduced penetrance of the mutant allele in an asymptomatic parent, or a de novo mutation. The risk to siblings depends on the genetic status of the proband’s parents. If one of the proband’s parents has a mutant allele, the risk to the sibs of inheriting the mutant allele is 50%. Individuals with autosomal dominant ataxia have a 50% chance of transmitting the mutant allele to each child.

Risk to family members: autosomal recessive hereditary ataxia

The parents of an individual affected with an autosomal recessive ataxia are obligate heterozygotes and therefore carry a single copy of a disease-causing mutation. In general, the heterozygotes are asymptomatic. Siblings of a proband have a 25% chance of being affected, a 50% chance of being a heterozygote carrier, and a 25% chance of being unaffected and not a carrier. Once it is established that an at-risk sib is unaffected, the chance of his/her being a carrier is two-thirds. All offspring of affected patients are obligate carriers.

Risk to family members: X-linked hereditary ataxia

The father of an affected male will not have the disease nor will he be a carrier of the mutation. However, women with an affected son and another affected male relative are obligate heterozygotes. The risk to siblings depends on the carrier status of the mother. If the mother of the proband has a disease-causing mutation, the chance of transmitting it in each pregnancy is 50%. Male siblings who inherit the mutation will be affected whereas female siblings inheriting the mutation will be carriers and usually not affected. If the proband with an X-linked disease represents a simplex (single occurrence in the family) and if the disease-causing mutation cannot be detected in the leukocyte DNA of the mother, the risk to siblings is low but greater than that of the general population because of the possibility of maternal germline mosaicism. The daughters of an affected male are all carriers whereas none of his sons will be affected or be carriers.

Related genetic counseling issues

Testing of at-risk asymptomatic adult relatives of individuals with autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia is possible after molecular genetic testing has identified the specific disorder and mutation in the family. Such testing should be performed in the context of formal genetic counseling. This testing is not useful in predicting age of onset, severity, type of symptoms, or rate of progression in asymptomatic individuals. Testing of asymptomatic at-risk individuals with nonspecific or equivocal symptoms is predictive testing, not diagnostic testing. When testing at-risk individuals, an affected family member should be tested first to confirm that the mutation is identifiable by currently available techniques. Results of testing of 29 asymptomatic persons at risk for autosomal dominant ataxias have been reported.77

Molecular genetic testing of asymptomatic individuals younger than 18 years who are at risk for adult-onset disorders for which no treatment exists is not considered appropriate, primarily because it negates the autonomy of the child with no compelling benefit. Furthermore, concern exists regarding the potential unhealthy adverse effects that such information may have on family dynamics, the risk of discrimination and stigmatization in the future, and the anxiety that such information may cause.

For more information, see also the National Society of Genetic Counselors resolution on genetic testing of children and the American Society of Human Genetics and American College of Medical Genetics points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents.

DNA banking. DNA banking is the storage of DNA (typically extracted from white blood cells) for possible future use. Because it is likely that testing methodology and our understanding of genes, mutations, and diseases will improve in the future, consideration should be given to banking DNA of affected individuals.

Prenatal testing. Prenatal diagnosis for some of the hereditary ataxias is possible by analyzing fetal DNA (extracted from cells obtained by chorionic villus sampling at about 10–12 weeks’ gestation or amniocentesis, usually performed at about 15–18 weeks’ gestation) for disease-causing mutations. The disease-causing allele(s) of an affected family member must be identified before prenatal testing can be performed.

Requests for prenatal testing for (typically) adult-onset diseases are not common. Differences in perspective may exist among medical professionals and within families regarding the use of prenatal testing, particularly if the testing is being considered for the purpose of pregnancy termination rather than early diagnosis. Although most centers would consider decisions about prenatal testing to be the choice of the parents, discussion of these issues is appropriate.

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis may be available for families in which the disease-causing mutation has been identified.

Management

Treatment of manifestations

Management of ataxias is usually directed at providing assistance for coordination problems through established methods of rehabilitation medicine and occupational and physical therapy. Patients can be evaluated for mobility-assist devices such as canes, walkers, and wheelchairs, which are useful for gait ataxia. Similarly, special devices are available to assist with handwriting, buttoning, and use of eating utensils.

Speech therapy may benefit persons with dysarthria. Computer devices are available to assist persons with severe speech deficits.

Parkinsonian features may respond to L-Dopa, and spasticity may respond to Baclofen or tizanadine.

Prevention of primary manifestations

Treatments are available for a few autosomal recessive ataxias: Vitamin E therapy for AVED, chenodeoxycholic acid for cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis, CoQ10 for CoQ10 deficiency, and dietary restriction of phytanic acid for Refsum disease. Idebenone may ameliorate the cardiac and neurologic manifestations of FRDA.78 No other specific treatments exist for hereditary ataxias.

Therapies under investigation

Underwood and Rubinsztein79 review potential strategies for treating ataxias associated with trinucleotide repeat expansions. RNA interference strategies have been suggested for some autosomal dominant SCAs.80 For further and up-to-date information, readers may search ClinicalTrials.gov for access to information on clinical studies for a wide range of diseases and conditions.

Resource

National Ataxia Foundation, 2600 Fernbrook Lane Suite 119, Minneapolis, MN 55447; Phone: 763.553.0020; http://www.ataxia.org.

Disclosure

T.D.B. received licensing fees from and is on the speaker’s bureau of Athena Diagnostics. S.J. declares no conflict of interest.

References

Finsterer J . Mitochondrial ataxias. Can J Neurol Sci 2009;36:543–553.

Paulson HL . The spinocerebellar ataxias. J Neuroophthalmol 2009;29:227–237.

Durr A . Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: polyglutamine expansions and beyond. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:885–894.

Schöls L, Amoiridis G, Büttner T, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Riess O . Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: phenotypic differences in genetically defined subtypes? Ann Neurol 1997;42:924–932.

Tezenas du Montcel S, Charles P, Goizet C, et al. Factors influencing disease progression in autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia and spastic paraplegia. Arch Neurol 2012;69:500–508.

Kerber KA, Jen JC, Perlman S, Baloh RW . Late-onset pure cerebellar ataxia: differentiating those with and without identifiable mutations. J Neurol Sci 2005;238:41–45.

Kraft S, Furtado S, Ranawaya R, et al. Adult onset spinocerebellar ataxia in a Canadian movement disorders clinic. Can J Neurol Sci 2005;32:450–458.

Maschke M, Oehlert G, Xie TD, et al. Clinical feature profile of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1-8 predicts genetically defined subtypes. Mov Disord 2005;20:1405–1412.

Schmitz-Hübsch T, Fimmers R, Rakowicz M, et al. Responsiveness of different rating instruments in spinocerebellar ataxia patients. Neurology 2010;74:678–684.

Ross OA, Rutherford NJ, Baker M, et al. Ataxin-2 repeat-length variation and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20:3207–3212.

Van Damme P, Veldink JH, van Blitterswijk M, et al. Expanded ATXN2 CAG repeat size in ALS identifies genetic overlap between ALS and SCA2. Neurology 2011;76:2066–2072.

Mantuano E, Romano S, Veneziano L, et al. Identification of novel and recurrent CACNA1A gene mutations in fifteen patients with episodic ataxia type 2. J Neurol Sci 2010;291:30–36.

Brkanac Z, Spencer D, Shendure J, et al. IFRD1 is a candidate gene for SMNA on chromosome 7q22-q23. Am J Hum Genet 2009;84:692–697.

Brkanac Z, Fernandez M, Matsushita M, et al. Autosomal dominant sensory/motor neuropathy with Ataxia (SMNA): Linkage to chromosome 7q22-q32. Am J Med Genet 2002;114:450–457.

Melberg A, Dahl N, Hetta J, et al. Neuroimaging study in autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy. Neurology 1999;53:2190–2192.

Trudeau MM, Dalton JC, Day JW, Ranum LP, Meisler MH . Heterozygosity for a protein truncation mutation of sodium channel SCN8A in a patient with cerebellar atrophy, ataxia, and mental retardation. J Med Genet 2006;43:527–530.

Coutinho P, Cruz VT, Tuna A, Silva SE, Guimarães J . Cerebellar ataxia with spasmodic cough: a new form of dominant ataxia. Arch Neurol 2006;63:553–555.

Koob MD, Moseley ML, Schut LJ, et al. An untranslated CTG expansion causes a novel form of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA8). Nat Genet 1999;21:379–384.

Ikeda Y, Daughters RS, Ranum LPW . Bidirectional expression of the SCA8 expansion mutation: one mutation, two genes. Cerebellum 2008;7:150–158.

Teive HA, Munhoz RP, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Werneck LC, Ashizawa T . Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 - A review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011;17:655–661.

La Spada AR . Trinucleotide repeat instability: genetic features and molecular mechanisms. Brain Pathol 1997;7:943–963.

van de Warrenburg BP, Sinke RJ, Verschuuren-Bemelmans CC, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxias in the Netherlands: prevalence and age at onset variance analysis. Neurology 2002;58:702–708.

Silveira I, Miranda C, Guimarães L, et al. Trinucleotide repeats in 202 families with ataxia: a small expanded (CAG)n allele at the SCA17 locus. Arch Neurol 2002;59:623–629.

Watanabe H, Tanaka F, Matsumoto M, et al. Frequency analysis of autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias in Japanese patients and clinical characterization of spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Clin Genet 1998;53:13–19.

Kim JY, Park SS, Joo SI, Kim JM, Jeon BS . Molecular analysis of Spinocerebellar ataxias in Koreans: frequencies and reference ranges of SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, SCA6, and SCA7. Mol Cells 2001;12:336–341.

Matsumura R, Futamura N, Ando N, Ueno S . Frequency of spinocerebellar ataxia mutations in the Kinki district of Japan. Acta Neurol Scand 2003;107:38–41.

Moseley ML, Benzow KA, Schut LJ, et al. Incidence of dominant spinocerebellar and Friedreich triplet repeats among 361 ataxia families. Neurology 1998;51:1666–1671.

Embiruçu EK, Martyn ML, Schlesinger D, Kok F . Autosomal recessive ataxias: 20 types, and counting. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2009;67:1143–1156.

Metz G, Coppard N, Cooper JM, et al. Rating disease progression of Friedreich’s ataxia by the International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale: analysis of a 603-patient database. Brain 2013;136(Pt 1):259–268.

Di Donato I, Bianchi S, Federico A . Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency: update of molecular diagnosis. Neurol Sci 2010;31:511–515.

Hentati F, El-Euch G, Bouhlal Y, Amouri R . Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency and abetalipoproteinemia. Handb Clin Neurol 2012;103:295–305.

Bomar JM, Benke PJ, Slattery EL, et al. Mutations in a novel gene encoding a CRAL-TRIO domain cause human Cayman ataxia and ataxia/dystonia in the jittery mouse. Nat Genet 2003;35:264–269.

Tada M, Yokoseki A, Sato T, Makifuchi T, Onodera O . Early-onset ataxia with ocular motor apraxia and hypoalbuminemia/ataxia with oculomotor apraxia 1. Adv Exp Med Biol 2010;685:21–33.

Le Ber I, Moreira MC, Rivaud-Péchoux S, et al. Cerebellar ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 1: clinical and genetic studies. Brain 2003;126(Pt 12):2761–2772.

Onodera O . Spinocerebellar ataxia with ocular motor apraxia and DNA repair. Neuropathology 2006;26:361–367.

Anheim M, Monga B, Fleury M, et al. Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2: clinical, biological and genotype/phenotype correlation study of a cohort of 90 patients. Brain 2009;132(Pt 10):2688–2698.

Asaka T, Yokoji H, Ito J, Yamaguchi K, Matsushima A . Autosomal recessive ataxia with peripheral neuropathy and elevated AFP: novel mutations in SETX. Neurology 2006;66:1580–1581.

Nikali K, Suomalainen A, Saharinen J, et al. Infantile onset spinocerebellar ataxia is caused by recessive mutations in mitochondrial proteins Twinkle and Twinky. Hum Mol Genet 2005;14:2981–2990.

Anttonen AK, Mahjneh I, Hämäläinen RH, et al. The gene disrupted in Marinesco-Sjögren syndrome encodes SIL1, an HSPA5 cochaperone. Nat Genet 2005;37:1309–1311.

Horvers M, Anttonen AK, Lehesjoki AE, et al. Marinesco-Sjögren syndrome due to SIL1 mutations with a comment on the clinical phenotype. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2013;17:199–203.

Winterthun S, Ferrari G, He L, et al. Autosomal recessive mitochondrial ataxic syndrome due to mitochondrial polymerase gamma mutations. Neurology 2005;64:1204–1208.

Van Goethem G, Luoma P, Rantamäki M, et al. POLG mutations in neurodegenerative disorders with ataxia but no muscle involvement. Neurology 2004;63:1251–1257.

Bouhlal Y, Amouri R, El Euch-Fayeche G, Hentati F . Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay: an overview. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011;17:418–422.

Mrissa N, Belal S, Hamida CB, et al. Linkage to chromosome 13q11-12 of an autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia in a Tunisian family. Neurology 2000;54:1408–1414.

Pulst SM, Filla A . Ataxias on the march from Quebec to Tunisia. Neurology 2000;54:1400–1401.

Wanders RJA, Waterham HR, Leroy BP . Refsum disease. In: GeneReviews at GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource (online resource). Copyright University of Washington: Seattle, Washington. 1997–2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1353. Accessed 11 October 2012.

Fiskerstrand T, H’mida-Ben Brahim D, Johansson S, et al. Mutations in ABHD12 cause the neurodegenerative disease PHARC: an inborn error of endocannabinoid metabolism. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87:410–417.

Lamperti C, Naini A, Hirano M, et al. Cerebellar ataxia and coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology 2003;60:1206–1208.

Montero R, Pineda M, Aracil A, et al. Clinical, biochemical and molecular aspects of cerebellar ataxia and Coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Cerebellum 2007;6:118–122.

Takashima H, Boerkoel CF, John J, et al. Mutation of TDP1, encoding a topoisomerase I-dependent DNA damage repair enzyme, in spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy. Nat Genet 2002;32:267–272.

Walton C, Interthal H, Hirano R, Salih MA, Takashima H, Boerkoel CF . Spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy. Adv Exp Med Biol 2010;685:75–83.

Gironi M, Lamperti C, Nemni R, et al. Late-onset cerebellar ataxia with hypogonadism and muscle coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neurology 2004;62:818–820.

Swartz BE, Burmeister M, Somers JT, Rottach KG, Bespalova IN, Leigh RJ . A form of inherited cerebellar ataxia with saccadic intrusions, increased saccadic speed, sensory neuropathy, and myoclonus. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002;956:441–444.

Tranebjaerg L, Teslovich TM, Jones M, et al. Genome-wide homozygosity mapping localizes a gene for autosomal recessive non-progressive infantile ataxia to 20q11-q13. Hum Genet 2003;113:293–295.

Assoum M, Salih MA, Drouot N, et al. Rundataxin, a novel protein with RUN and diacylglycerol binding domains, is mutant in a new recessive ataxia. Brain 2010;133(Pt 8):2439–2447.

Boycott KM, Flavelle S, Bureau A, et al. Homozygous deletion of the very low density lipoprotein receptor gene causes autosomal recessive cerebellar hypoplasia with cerebral gyral simplification. Am J Hum Genet 2005;77:477–483.

Gros-Louis F, Dupré N, Dion P, et al. Mutations in SYNE1 lead to a newly discovered form of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. Nat Genet 2007;39:80–85.

Dupré N, Gros-Louis F, Chrestian N, et al. Clinical and genetic study of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 1. Ann Neurol 2007;62:93–98.

Dixon-Salazar T, Silhavy JL, Marsh SE, et al. Mutations in the AHI1 gene, encoding jouberin, cause Joubert syndrome with cortical polymicrogyria. Am J Hum Genet 2004;75:979–987.

Parisi M, Glass I . Joubert syndrome. In: GeneReviews at GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource (online resource). Copyright University of Washington: Seattle, Washington. 2003–2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1325. Accessed 31 October 2012.

Sellick GS, Barker KT, Stolte-Dijkstra I, et al. Mutations in PTF1A cause pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis. Nat Genet 2004;36:1301–1305.

Sparks SE, Krasnewich DM . Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation. Overview In: GeneReviews at GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource (online resource). Copyright University of Washington: Seattle, Washington. 2005–2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1332. Accessed 31 October 2012.

Renbaum P, Kellerman E, Jaron R, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy with pontocerebellar hypoplasia is caused by a mutation in the VRK1 gene. Am J Hum Genet 2009;85:281–289.

Cassandrini D, Biancheri R, Tessa A, et al. Pontocerebellar hypoplasia: clinical, pathologic, and genetic studies. Neurology 2010;75:1459–1464.

Doi H, Yoshida K, Yasuda T, et al. Exome sequencing reveals a homozygous SYT14 mutation in adult-onset, autosomal-recessive spinocerebellar ataxia with psychomotor retardation. Am J Hum Genet 2011;89:320–327.

D’Hooghe M, Selleslag D, Mortier G, et al. X-linked sideroblastic anemia and ataxia: a new family with identification of a fourth ABCB7 gene mutation. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2012;16:730–735.

Berry-Kravis E, Abrams L, Coffey SM, et al. Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: clinical features, genetics, and testing guidelines. Mov Disord 2007;22:2018–30, quiz 2140.

Leehey MA . Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: clinical phenotype, diagnosis, and treatment. J Investig Med 2009;57:830–836.

Da Pozzo P, Cardaioli E, Malfatti E, et al. A novel mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Pro) gene associated with late-onset ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa, deafness, leukoencephalopathy and complex I deficiency. Eur J Hum Genet 2009;17:1092–1096.

Pfeffer G, Blakely EL, Alston CL, et al. Adult-onset spinocerebellar ataxia syndromes due to MTATP6 mutations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2012;83:883–886.

Gupta A, Jankovic J . Spinocerebellar ataxia 8: variable phenotype and unique pathogenesis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2009;15:621–626.

Gasser T, Finsterer J, Baets J, et al.; EFNS. EFNS guidelines on the molecular diagnosis of ataxias and spastic paraplegias. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:179–188.

Fujigasaki H, Tardieu S, Camuzat A, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 in the French population. Ann Neurol 2002;51:408–409.

Abele M, Bürk K, Schöls L, et al. The aetiology of sporadic adult-onset ataxia. Brain 2002;125(Pt 5):961–968.

Fogel BL, Lee JY, Lane J, et al. Mutations in rare ataxia genes are uncommon causes of sporadic cerebellar ataxia. Mov Disord 2012;27:442–446.

Tsuji S, Onodera O, Goto J, Nishizawa M ; Study Group on Ataxic Diseases. Sporadic ataxias in Japan–a population-based epidemiological study. Cerebellum. 2008;7:189–1897.

Goizet C, Lesca G, Dürr A ; French Group for Presymptomatic Testing in Neurogenetic Disorders. Presymptomatic testing in Huntington’s disease and autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias. Neurology 2002;59:1330–1336.

Meier T, Perlman SL, Rummey C, Coppard NJ, Lynch DR . Assessment of neurological efficacy of idebenone in pediatric patients with Friedreich’s ataxia: data from a 6-month controlled study followed by a 12-month open-label extension study. J Neurol 2012;259:284–291.

Underwood BR, Rubinsztein DC . Spinocerebellar ataxias caused by polyglutamine expansions: a review of therapeutic strategies. Cerebellum 2008;7:215–221.

Seyhan AA . RNAi: a potential new class of therapeutic for human genetic disease. Hum Genet 2011;130:583–605.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from Veterans Affairs Research and the National Center for Biotechnology Information. This overview represents a revised and updated version of Thomas D. Bird’s Hereditary Ataxia in GeneReviews at GeneTests: Medical Genetics Information Resource (online resource). Copyright University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, 1998–2012.http://www.genetests.org.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jayadev, S., Bird, T. Hereditary ataxias: overview. Genet Med 15, 673–683 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2013.28

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Novel CWF19L1 mutations in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia, autosomal recessive 17

Journal of Human Genetics (2023)

-

Parkinsonism in complex neurogenetic disorders: lessons from hereditary dementias, adult-onset ataxias and spastic paraplegias

Neurological Sciences (2023)

-

The Cost of Living with Inherited Ataxia in Ireland

The Cerebellum (2022)

-

A novel biallelic variant further delineates PRDX3-related autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia

neurogenetics (2022)

-

Patients’ Perspective in Hereditary Ataxia

The Cerebellum (2022)