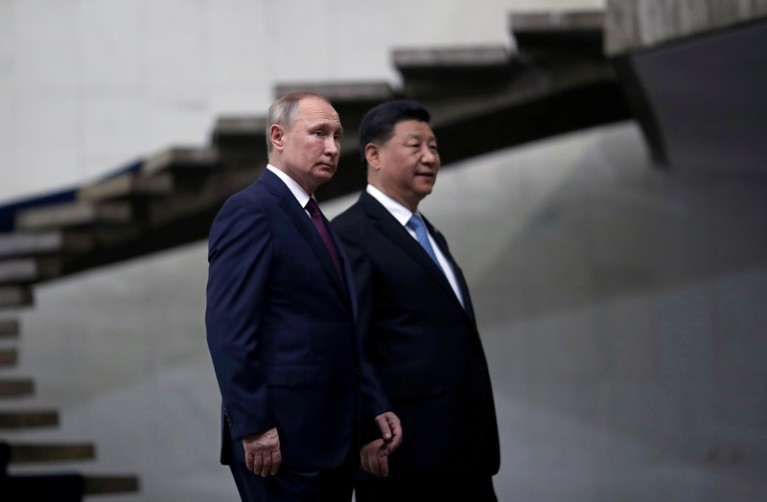

Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping are both looking to stay in power beyond their usual term limits.Credit: Ueslei Marcelino/Reuters

This week, Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, asked the courts to allow him to change the nation’s constitution, so it would no longer prevent him from standing for re-election beyond 2024. If he succeeds — and keeps winning elections — Putin could remain president until 2036, more than 35 years after coming to power.

The move to extend Putin’s power has major consequences for Russian society — including science. Putin’s government helped to stabilize research after the chaos of the early 1990s that followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Papers authored by Russian scientists more than doubled in the decade between 2006 and 2016. And in 2018, the government allocated 170 billion roubles (US$3 billion at the time) for fundamental research and development, a 25% rise over the 2017 basic-science budget.

Russia aims to revive science after era of stagnation

But, as we report this week in a News Feature, Russia still has a long way to go before it reaches its full potential in research and innovation. And as the president looks to strengthen his grip on power, some researchers are rightly concerned. Research funding — at 1% of gross domestic product — is far below that of advanced industrialized nations, and promises to increase this have not been kept. Furthermore, bureaucratic and political interference in research is strong.

Coincidentally, China is pursuing closer scientific contacts with Russia, and at a time of economic crisis, these are being welcomed. This year has been designated as the year of Russian–Chinese science cooperation: 800 activities are planned, including joint research in fields ranging from archaeology to artificial intelligence.

In addition to this, Russia is a leading participant in China’s global network of science organizations in the countries that are part of its Belt and Road initiative, known as ANSO (Alliance of International Science Organizations). The organization’s next annual meeting is due to take place in Moscow in May — although this will probably be postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Two years ago, we remarked in these columns how China could help to awaken “the sleeping bear of Russian science”. China seems to be doing that, but it is happening as both China and Russia are being isolated by some Western countries. For example, most official US–Russian scientific ties have been suspended since 2014 after Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula. That is a short-sighted strategy. Even at the height of the cold war, researchers from Eastern and Western nations were encouraged to keep collaborations going. It is not too late to change course.

Russia aims to revive science after era of stagnation

Russia aims to revive science after era of stagnation

Russian science chases escape from mediocrity

Russian science chases escape from mediocrity

How Putin can restore Russian research

How Putin can restore Russian research