Economics and finance: meet science.Credit: Sebastien Micke/Paris Match/Getty

“He has enriched the world with works that will long remain monuments of science.”

Reading Nature’s 1873 obituary1 of the philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill, you would think economists and scientists were two sides of the same research coin — that economics was welcomed as part of the scientific tradition, and vice versa. But that was then. The age of the polymath was coming to an end and researchers were becoming single-discipline specialists. Economists and natural scientists drew apart as universities organized their researchers into engineering, humanities, science and social-science faculties.

Well over a century later, the pendulum is swinging back. Economists and scientists are moving closer, as universities and funding agencies embrace more multi- and transdisciplinary research. Over at the World Health Organization, a chief-economist post is being considered.

Nature will soon appoint an economics editor, following the lead of Nature Climate Change, Nature Energy, Nature Sustainability, Nature Human Behaviour and Nature Communications. We recognize the importance of reuniting economics with other disciplines.

These moves could not have come soon enough. The world faces a mountain of challenges — and to find solutions, humanity must approach them in multiple ways. One of the biggest puzzles concerns the research enterprise itself. Economists have been pointing out for some years that we don’t fully understand why the results of research and innovation — which have ushered in the digital age along with other transformations — are not benefiting everyone in society, as seen for example in wage stagnation and widening inequality. But relatively few natural scientists or engineers have taken up this question.

At the same time, more economists than ever are reaching across disciplinary divides, and they want journals to recognize the results. “I have younger colleagues interested in the economics of data, artificial intelligence, pharmaceuticals. They want to work with — and publish with — scientists,” says economist Diane Coyle of the University of Cambridge, UK. But she and others say that they struggle to publish work on big societal problems — co-authored by natural scientists or social scientists from other disciplines — because such work can fall outside the remit of economics and science journals.

But it matters. In 2011, not long after the global financial crisis of 2008, Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane worked with theoretical ecologist Robert May to harness infectious-disease modelling techniques to investigate risks and vulnerabilities in the global financial system. Their resulting Nature paper2 showed researchers how they could collaborate to understand other complex networks, such as those involving trade or information. “I am continually surprised at how much impact that paper has had,” says Haldane.

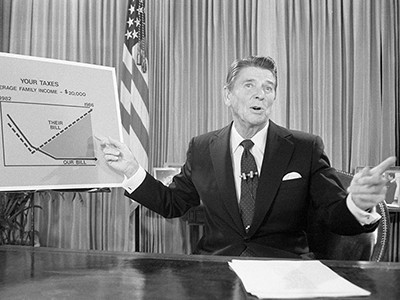

The dangers of fringe economics in government

Jim O’Neill, former head of economics research at global investment bank Goldman Sachs in New York City, reached across the aisle to study the financing of new antimicrobial drugs (see go.nature.com/2e3bkmj). Economics research, he says, could demonstrate the costs and benefits of investing more in public health, to encourage governments in low- and middle-income countries to make such investments. Similarly, with the pharmaceutical industry and governments still not properly funding development of a badly needed new generation of antibiotics, he says, biomedical researchers need to collaborate with economists and public-policy specialists to create a workable financial model.

The environment — including biodiversity and climate change — is one area in which natural-science researchers and economists do have a long-standing shared interest. Economics research, for example, is assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and Nature’s research and comment sections publish influential work from ecological and environmental economists3.

But here, too, there’s potential for more joint problem-solving. Success in many of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals will require an understanding of how far economies can continue to grow within planetary limits. But there are many views on this, including various intellectual traditions in economics. Some economists, for example, argue that a planet under pressure from industrialization cannot withstand continued economic growth. But for others, growth is essential to alleviating poverty — as long as growth becomes greener.

To solve these problems, economists, natural and social scientists and engineers must all engage with and learn from each other. It is often too easy to say ‘more research will help’. But here, it is necessary — especially economics research, which we look forward to publishing.

Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against

Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against

When capitalisms collide

When capitalisms collide

The dangers of fringe economics in government

The dangers of fringe economics in government