Small research teams are more likely to publish papers that pose new ideas, as opposed to elaborating on existing questions.Credit: Keith Brofsky/Getty

Modern science is big, and author lists are growing. The celebrated 2015 paper estimating the Higgs boson’s mass had a record-breaking 5,154 authors. And the number of papers with more than 1,000 authors has surged.

At the other end of the scale, single-author papers are scarce — almost non-existent in some fields. In an ecology journal, for instance, they dropped from 60% of publications in the 1960s, to just 4% over the past decade (J. Barlow et al. J. Appl. Ecol. 55, 1–4; 2018). And the average number of authors per paper rose from 3.8 in 2007 to 4.5 in 2011.

There are many reasons underlying the shift, including the enormous growth of the scientific community and the increasing amount of evidence presented in a single paper. But what are the consequences? Is the nature of research changing as larger teams are doing the work?

The authors of a paper in Nature this week tried to find out, by examining the “disruptiveness” of papers published over the past half a century (L. Wu et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0941-9; 2019). They measured the disruptiveness of a paper by looking closely at the citations it accrues: an article was considered to have posed a new idea, as opposed to solving or elaborating on existing questions, when the papers that cite it did not also cite many of its references.

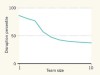

The researchers found that, by this metric, teams containing fewer than five people tend to produce more disruptive work, whereas larger teams generate more incremental or consolidatory work. This held true for papers, patents and code, and across fields and time. This makes sense — large teams can marshal technical expertise and resources to tackle well-defined problems, but might be less likely to conceive unconventional ideas or be nimble enough to pursue them.

The effect appears to arise as a result of team dynamics, rather than through qualitative differences between individuals in different-sized teams. The authors showed that the same person tends to produce more disruptive work when working in smaller teams than in larger ones.

So is research becoming more mundane as the teams grow? Are genuinely new ideas being squelched by group-think? That seems unlikely: scientific advance comes in many forms, and research needs both disruption and consolidation, from small teams and large. The future health of the research ecosystem depends on a diverse range of team sizes. Research funders and policymakers should take note.

Read the paper: Large teams develop, and small teams disrupt, science and technology

Read the paper: Large teams develop, and small teams disrupt, science and technology

News & Views: Small research teams ‘disrupt’ science more radically than large ones

News & Views: Small research teams ‘disrupt’ science more radically than large ones