The response of Hong Kong to bird flu shows how scientists can address local needs.Credit: Dale de la Rey/AFP/Getty

One of the most commonly stated goals of science and scientists is to work to improve society. But which society? The needs and circumstances of people, communities and regions across the world are very different — from energy use and disease threats to natural-resource availability and pollution.

In a special issue this week, Nature explores how some of these local needs are being addressed across five strong science centres in East Asia: Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. Over the past few decades, each member of this diverse group has evolved its own model of how to pursue research successfully. Impressively, some of their key achievements are those in which they have matched the science agenda to explicit and unique local requirements.

Nature special: Hubs of Asian science

That is a good model for others to follow, especially given that large numbers of people around the world are not well enough served by the agendas and interests that drive much of modern science. Nature has argued before that more scientists and funders should reach out to identify and tackle direct societal challenges in this way (Nature 542, 391; 2017).

Each of the economies we highlight has a unique history that has shaped its research and development. Take Malaysia, a peninsula and constellation of islands sandwiched between Thailand and Indonesia. In the 1970s, it started to shift its economic reliance on cheap products such as tin, rubber and cocoa to higher-value commodities such as natural gas and palm oil. It then used applied science to foster a booming electronics industry. Some of its major exports today include other products of applied research, including chemicals. Yet this success has come with relatively low investment in science and technology.

More unusual still, almost half of researchers there are women (see ‘Science in East Asia — by the numbers’). In a News Feature this week, among others, we profile Malaysian chemical engineer Suzana Yusup, who leads a centre that makes fuels from biomass waste, such as used cooking oil, rubber-seed oil and discarded distillate from palm-oil refineries. Her career has focused on green technologies that can help the environment and society.

How Malaysian science can improve lives as well as the economy

Scientists in Malaysia, which has a predominantly Muslim population, are also developing Halal substitute ingredients for food, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, reaping the benefits of a Halal economy that, in 2016, was worth US$2 trillion globally.

Malaysia demonstrates how applied science can generate the economic benefits that can allow officials to invest in societal needs. And it’s not alone. Singapore, along with South Korea and Taiwan, has long focused on applied projects across electronics, physics and materials science. The success of these has boosted its gross domestic product (GDP). And the Singaporean government is now putting some of that money into national priorities — health care and biomedical sciences among them. There’s a strong push to understand, detect and treat heart disease and cancers of the liver, stomach, breast and lung, which have a significant impact on Asian populations.

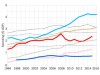

By most measures, South Korea is an impressive performer in science, making it a giant in the region. It invests more than 4% of its GDP in science and technology — much of it applied — and has a high density of researchers per head of population. Its output of scholarly articles has skyrocketed in the past two decades.

South Korean science needs restructuring

But South Korea is also choking under a cloud of air pollution, and, as physicist Han Woong Yeom at Pohang University of Science and Technology writes in a Comment piece, its science policy must be updated to address this and other national needs. That might already be happening. A 2015 analysis of development of the regional research and technology organization in Gyeonggi province suggested that policymakers had switched from a top-down approach to one that emphasizes the “detailed analysis of local industry needs” (S. Shin Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2, 424–431; 2015).

Not all scientists in conventional research-powerhouse economies might welcome such direct targeting of local problems, just as some frown when politicians talk up the need for applied science. But there does not have to be a trade-off between work that is of international quality and work that has a direct local impact. Hong Kong, for example, has grown into a hub for researchers investigating emerging infectious diseases, such as the avian influenza strain H5N1 and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), both of which originated in Asia. Those teams published papers in leading journals. But research there has also demonstrated that closing live-poultry markets for a day or two each month could dramatically reduce the spread of bird flu and cut the risk to people. That’s a win–win situation, the likes of which all societies should encourage — wherever they are.

Nature special: Hubs of Asian science

Nature special: Hubs of Asian science

Science in East Asia — by the numbers

Science in East Asia — by the numbers

The science stars of East Asia

The science stars of East Asia

South Korean science needs restructuring

South Korean science needs restructuring

How Malaysian science can improve lives as well as the economy

How Malaysian science can improve lives as well as the economy

How to build a lab in East Asia’s science hot spots

How to build a lab in East Asia’s science hot spots