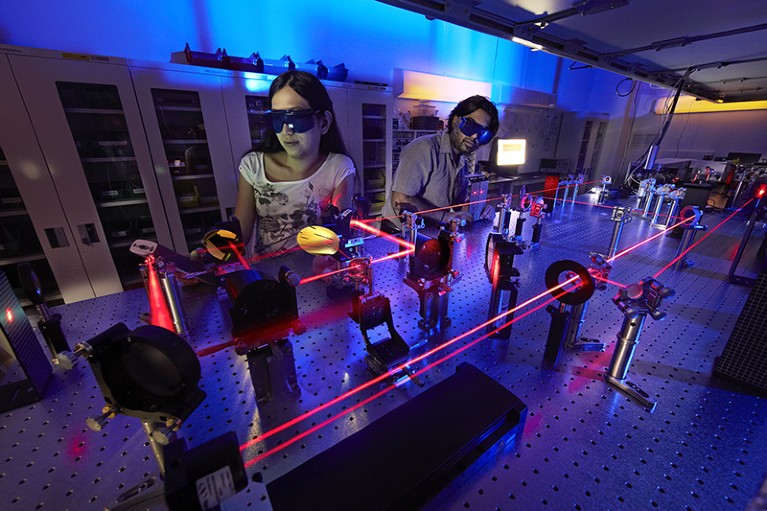

Institutions have a moral and ethical duty to make scientific research more diverse and representative.Credit: OIST

Lab groups, departments, universities and national funders should encourage participation in science from as many sectors of the population as possible. It’s the right thing to do — both morally and to help build a sustainable future for research that truly represents society.

A more representative workforce is more likely to pursue questions and problems that go beyond the narrow slice of humanity that much of science (biomedical science in particular) is currently set up to serve. Widening the focus is essential if publicly funded research is to protect and preserve its mandate to work to improve society. For example, a high proportion of the research that comes out of the Western world uses tissue and blood from white individuals to screen drugs and therapies for a diverse population. Yet it is well known that people from different ethnic groups can have different susceptibility to some diseases.

Many people are working to improve diversity in science and the scientific workforce. Some have been trying hard for decades, but not all are succeeding. This week, Nature highlights examples of success from across the world. They are inspiring, and show what can — and must — be done.

What does it take to make an institution more diverse?

To boost recruitment and participation in science among some under-represented groups is difficult. Statistics from the US National Science Foundation show that the representation of minority ethnic groups in the sciences would need to more than double to match the groups’ overall share of the US population.

As we highlight in a Careers piece this week, there are steps that groups, departments and institutions can take to try to draw from a broader pool of talent. Some of these demand effort to reach out to under-represented communities, to encourage teenagers who might otherwise not consider science as an option. Even the wording of job advertisements can put people off — candidates from some backgrounds might be less likely to consider themselves ‘outstanding’ or ‘excellent’, and so might not even apply. Yet diversity efforts should not stop when people are through the door. To retain is as important as to recruit — mentoring and support is essential for all young scientists, and especially so for those who have been marginalized by academic culture.

Projects to boost participation are often the passion and work of a few dedicated individuals. More institutions and funders should seek, highlight and support both the actions and the individuals.

These labs are remarkably diverse — here’s why they’re winning at science

There are moral and ethical reasons for institutions to act. And there are other potential benefits, too. Firms are recognizing that diversity — and associated attitudes and behaviours — is a business issue. A report from consultancy firm McKinsey earlier this year was just the latest to set out the healthy relationship between a company’s approach to inclusion and diversity and its bottom line. The report, Delivering through Diversity, reaffirms the positive link between a firm’s financial performance and its diversity — which it defines in terms of the proportion of women and the ethnic and cultural composition of the leadership of large companies.

Could something similar be true in science? As we discuss in a News Feature this week, some studies suggest that a team with a good mix of perspectives is associated with increased productivity.

Concerted action to effect change on recruitment and retention can and does make a difference (see T. Hodapp and E. Brown Nature 557, 629–632; 2018). More effort across the board is overdue. The lack of diversity in science is everyone’s problem. Everyone has a responsibility to look around them, to see the problem for what it is, and to act — not just to assume it is someone else’s job to fix it.

These labs are remarkably diverse — here’s why they’re winning at science

These labs are remarkably diverse — here’s why they’re winning at science

What does it take to make an institution more diverse?

What does it take to make an institution more diverse?

Making physics more inclusive

Making physics more inclusive

When will clinical trials finally reflect diversity?

When will clinical trials finally reflect diversity?

Strength in diversity

Strength in diversity