Abstract

This article is addressed to endocrinologists treating patients with diabetic complications as well as to basic scientists studying an elusive link between diseases and aging. It answers some challenging questions. What is the link between insulin resistance (IR), cellular aging and diseases? Why complications such as retinopathy may paradoxically precede the onset of type II diabetes. Why intensive insulin therapy may initially worsen retinopathy. How nutrient- and insulin-sensing mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway can drive insulin resistance and diabetic complications. And how rapamycin, at rational doses and schedules, may prevent IR, retinopathy, nephropathy and beta-cell failure, without causing side effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

Glucose, amino and fatty acids, insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) activate the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway.

-

Overactivation of the mTOR pathway causes insulin resistance.

-

mTOR is involved in diabetic complications.

-

mTOR is involved in aging and age-related diseases.

-

Rapamycin extends life span in all species tested, including mice.

Open Questions

-

What is the link between cellular and organismal aging?

-

Will rapamycin (and other rapalogs) prevent diabetic complications in humans?

-

How to combine rapamycin and insulin?

-

Can intermittent schedules of rapamycin prevent type II diabetes, given that chronic overdosing of rapamycin can cause glucose intolerance?

Microvascular complications of diabetes such as retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy develop in 30–50% of patients with diabetes. These complications lead to blindness, renal failure and foot ulceration.1

There are two forms of diabetes. Type I diabetes (also known as insulin-dependent or juvenile diabetes) is caused by absolute insulin insufficiency due to autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. Type II diabetes (insulin-independent or adult-onset diabetes) is initiated by insulin resistance (IR) in muscle, liver and adipose tissues. Initially, an increase in insulin secretion by pancreatic beta cells compensates for IR. If/when beta cells fail, then glucose levels increase. When either fasting glucose levels or oral glucose tolerance test reach 126 and 200 mg/l, respectively, then diabetes is diagnosed. Although glucose control with intensive insulin therapy decreases the incidence of complications, diabetes remains a major cause of new-onset blindness, end-stage renal disease and lower leg amputation.2

There are two puzzling observations. First, complications can precede the onset of type II diabetes. Second, intensive insulin therapy may initially worsen the progression of retinopathy in both types I and type II diabetes.

Puzzle One: Complications may Precede Type II Diabetes

In type II diabetes, the onset of chronic complications may occur at least 4–7 years before clinical diagnosis of diabetes, in other words, before hyperglycemia.3, 4, 5 The simplest explanation is that diabetes may be diagnosed too late. Yet, another possibility is that complications may precede type II diabetes, if both beta-cell failure and retinopathy are independently caused by IR. Regardless of patient’s progression to diabetes, IR predicts retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy. Neuropathy is already present in 10–18% of patients at the time of diabetes diagnosis.6 The pre-diabetic state of IR is a risk factor for neuropathy7, 8 and nephropathy9 and is associated with retinopathy.10 Approximately 8% of the pre-diabetic population has retinopathy.11 Furthermore, retinopathy predicts subsequent risk of diabetes.12

Patients with IR are at increased risk for death and morbidity due to myocardial infarction, stroke, and large-vessel occlusive disease due to atherosclerosis.13 The risk of macrovascular disease is increased before glucose levels reach the diagnostic threshold for ‘diabetes,’ and 25% of newly diagnosed diabetics already have overt cardiovascular disease.14

Puzzle Two: Intensified Insulin Treatment and Retinopathy

In some cases, intensified insulin treatment, while controlling glucose, paradoxically worsened diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy.6, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 As we will discuss later, insulin therapy may accelerate complications because insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) activate mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR).

The mTOR Pathway

Target of rapamycin (TOR), which in mammals is known as mTOR, is a cytoplasmic kinase that regulates cell growth and metabolism in response to mitogens (such as IGF-I and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)), nutrients (amino acids, glucose and fatty acids), hormones including insulin and cytokines.22, 23, 24, 25 The nutrient-sensing mTOR pathway is essential for development and growth of the young organism. But later in life, when growth has been completed, mTOR drives cellular and organismal aging.26, 27 In particular, mTOR converts cellular quiescence into senescence.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 Senescent cells are hyperfunctional, hypersecretory, pro-inflammatory and signal resistant (e.g., insulin resistant).38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Slowly, but inevitably, these cellular hyperfunctions lead to age-related diseases.44, 45, 46, 47 Not surprisingly, mTOR is involved in age-related diseases.48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 Rapamycin slows down aging, prevents age-related diseases and extends maximal lifespan in mice.55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70

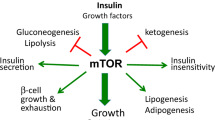

It is important to emphasize that both glucose and insulin activate mTOR (Figure 1). Thus, high glucose levels activate mTOR. By normalizing glucose levels, insulin therapy may de-activate mTOR. On the other hand, insulin itself activates the mTOR pathway. Furthermore, hyperinsulinemia itself may cause IR.71

mTOR and IR (via a feedback loop) in fat/muscle/liver cells. Insulin via insulin receptor substrate 1/2 (IRS1/2) activates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/S6K pathway. The mTOR/S6K pathway is also activated by nutrients such as glucose, TNF and numerous other factors. The mTOR/S6K pathway in turn inactivates IRS1/2, thus causing IR

Hyperactivation of mTOR and IR

Overactivated mTOR causes IR,72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78 mTOR activates S6 kinase (S6K), which in turn causes phosphorylation and degradation of insulin receptor substrate 1/2. This impairs insulin signaling (Figure 1). Also, mTOR causes IR by affecting growth factor receptor-bound protein 10.79, 80 Thus, hyperactivation of mTOR causes IR, by at least two mechanisms.

For example, in fat-fed rodents, the mTOR pathway is activated, leading to impaired insulin signaling and IR.74, 81 Increased insulin levels (hyperinsulinemia) itself causes IR, preventable by rapamycin.71 In humans, infusion of amino acids activates mTOR/S6K1, which causes a feedback IR in skeletal muscle.75, 76 Oral rapamycin blunted mTOR activation, preventing nutrient-induced IR in humans.82 Also, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and pro-inflammatory cytokines impair insulin signaling by activating mTOR.83 Noteworthy, aging is associated with pro-inflammation.84, 85 Although nutrients activate mTOR, dietary (calorie) restriction de-activates mTOR. This may explain why low calorie diet reduces IR.86 In some conditions, physical activity inhibits mTOR/S6K1 signaling in rat skeletal muscle, restoring insulin sensitivity.87 Thus, activation of mTOR in liver, muscle or adipose tissues is manifested as IR. How is hyperactivation of mTOR manifested in the retina?

mTOR and Retinopathy

Excessive growth of small blood vessels (angiogenesis or neovascularization) contributes to retinopathy (Figure 2). VEGF stimulates angiogenesis and causes blood–retinal barrier breakdown.88, 89 Synthesis of VEGF is stimulated via the insulin/mTOR pathway90, 91 in retinal pigment epithelial cells.92, 93, 94, 95 Insulin and IGF-1 are involved in angiogenesis and diabetic retinopathy.92, 15, 16, 17, 18, 96, 97 This explains observations that intensified insulin treatment may worsen diabetic retinopathy.6, 15, 17, 18, 19, 88, 97, 98

Rapamycin blocks insulin-induced hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and senescence of retinal cells95, 99 and inhibits retinal and choroidal neovascularization in mice.100 Rapamycin prevents retinopathy in aging-accelerated rats.101, 102 Noteworthy, rapamycin prevented retinopathy without decreasing VEGF levels.101 Subconjunctival rapamycin was studied for the treatment of diabetic macular edema.103

Beta-Cell Hyperfunction and Failure

Glucose, amino acids and fatty acids activate mTOR, thus causing expansion and hypertrophy of beta cells as well as increasing insulin secretion. Initially, this hyperfunction of beta cells compensates for IR, preventing hyperglycemia. However, it is hyperfunction that eventually causes beta-cell failure (diabetes). Beta-cell failure depends on genetic predisposition.107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113

In mice with hyperactive mTOR, islet mass is initially increased because of hypertrophy of the beta cells. These mice also exhibit high insulin and low glucose at young ages. After 40 weeks of age, however, the mice develop progressive hyperglycemia and hypoinsulinemia accompanied by a reduction in islet mass due to a decrease in the number of beta cells. Hyperactive mTOR regulates pancreatic beta-cell mass in a biphasic manner.114 Rapamycin prevents hyperinsulinemia in mice on high-fat diet.115, 116

How does hyperactivated mTOR cause beta-cell failure? Initially, mTOR stimulates beta-cell functions causing hyperfunction. Then, chronic hyperstimulation of mTOR renders beta cells resistant to IGF-1 and insulin, fostering cell death.107, 112, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124 In theory, a short-term treatment with rapamycin may re-sensitize cells to insulin and pro-survival signals.125, 126

Potential Applications of Rapamycin

Prevention of negative effects of insulin therapy

By activating mTOR, insulin therapy can cause its negative effects. First, mTOR induces HIF, mitogens and cytokines, contributing to pro-inflammation and neo-angiogenesis (Figure 3a). Second, hyperactivation of mTOR causes feedback IR (Figure 3a). These negative effects are downstream from mTOR (Figure 3). In contrast, therapeutic effects (glucose utilization) of insulin are mostly upstream of mTOR (Figure 3). Therefore, pre-treatment with rapamycin will block negative effects of insulin, while preserving its positive effect on glucose metabolism (Figure 3b).

Pre-treatment with rapamycin may prevent negative effects of insulin therapy. (a) Insulin stimulates glucose uptake and metabolism. Simultaneously, insulin activates the mTOR/S6K pathway, causing induction of HIF-1, IR and cell senescence. (b) Acute treatment with rapamycin is expected to prevent negative side effects of insulin, while sparing most effects on glucose metabolism. Short-term courses of rapamycin are expected to restore insulin sensitivity

Restoration of insulin sensitivity in hyperglycemia

Glucose activates mTOR, which by feedback loop can cause IR. In fact, very high levels of glucose cause IR and decrease glucose uptake.127, 128, 129 To overcome resistance, high doses of insulin may be needed, that is potentially harmful because of glucose fluctuations. In theory, pre-treatment with rapamycin would reduce IR in such patients. If so, then instead of high doses of insulin, rapamycin plus regular or low doses of insulin could be effective.

Prevention of beta-cell failure

Beta cells hyperfunction may eventually lead to beta-cell failure.107, 114, 117, 118, 122, 123, 124, 125 As we discussed previously125, 126 and here, mTOR renders beta cells unresponsive to pro-survival factors. In theory, intermittent or short-term treatment with rapamycin may decrease hyperfunction of beta cells and restore their responsiveness to pro-survival factors like IGF-I. In transplant organ recipients, rapamycin is used at high doses and daily for many years (long-term treatment). In contrast, to prevent beta-cell failure due to IR, it might be feasible to use rapamycin as a pulse (intermittent) treatment and at low doses.125, 126 Such therapy might actually preserve and improve beta-cell functions. During rapamycin treatment, beta cells would ‘rest’ from hyperstimulation. Following rapamycin withdrawal, beta cells would re-acquire the capacity to adapt.

Prevention of diabetic complications and cancer

As we already discussed, rapamycin prevents retinopathy, neuropathy and atherosclerosis.100, 101, 104, 105, 106, 130, 131, 132 Metabolic syndrome and aging stroma increase cancer risk (see Blagosklonny133, 134 and Mercier et al.135). Noteworthy, rapamycin decreases production of lactic acid by human cells136 and thus potentially can found application in the treatment of lactate acidosis. Albeit at lesser degree than rapamycin, metformin also inhibits mTOR, aging and cancer.137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145 Rapamycin analogs are used as anticancer drugs in part because the mTOR pathway is almost obligatory activated in cancer cells.146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152

Short-Term (Acute) Rapamycin may Reverse IR

Calorie restriction, metformin and thiazolidinediones reverse IR in part by activating AMPK and by inhibiting the mTOR pathway.73, 77, 153, 154 In healthy volunteers, a single dose pre-treatment with rapamycin abrogated nutrient-induced IR.82 Furthermore, prolonged treatment with rapamycin can lead to beneficial metabolic switch.155 However, in some animal models, chronic treatment with rapamycin can cause a peculiar type of IR at least, which resembles so called ‘starvation diabetes’.

Starvation Pseudo-Diabetes or Benevolent Glucose Intolerance

As we discussed, overactivation of mTOR causes IR. Yet, prolonged and profound inhibition of mTOR can cause IR, especially in certain strains of mice.156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161 This condition resembles ‘starvation diabetes’, a reversible condition.125, 126 First during starvation, low insulin and IR decrease the use of glucose by the muscle, fat and the liver, thus sparing glucose for the brain. (The brain crucially depends on glucose and ketones). As peripheral tissues do not use glucose, starvation is manifested by glucose intolerance. For example, if the starved subject ingests glucose, glucose may appear in the urine. Second, lipolysis is increased, providing fatty acids for ketogenesis. Third, owing to hepatic IR, the liver produces glucose and ketones to feed the brain. Therefore, starvation superficially resembles diabetes. However, this is not a true diabetes but rather benevolent glucose intolerance or benevolent pseudo-diabetes. In fact, starvation, fasting and calorie restriction do not cause ‘diabetes complications’ such as neuropathy or retinopathy or atherosclerosis.125, 126 In contrast, calorie restriction prevents diabetes and diabetic complications and extends life span.

By the definition of nutrient-sensing pathways, the nutrient- and insulin-sensing mTOR pathway is deactivated during fasting.162 Deactivation of mTOR increases longevity and health span.47 Rapamycin, which is a starvation-mimetic, causes lipolysis and some other starvation-like alterations.125 If chronic high-dose rapamycin treatment is associated with diabetes-like conditions, this must be benevolent pseudo-diabetes. In contrast to type II diabetes, benevolent IR due to mTOR deactivation extends life- and health span.126

mTOR-Centric Model

As suggested, ‘having a single mechanism to explain the link between obesity, IR and type II diabetes would be ideal’.163 Numerous factors (glucose, insulin, amino acids, fatty acids, TNF and inflammatory cytokines), protein kinase C (PKC) activates the nutrient-sensing mTOR pathway. In contrast, adiponectin deactivates mTOR.22, 83, 164 Logically, overactivation of the nutrient-sensing pathway is a unifying factor in metabolic disorders.

It was noticed that complications of type II diabetes and type II diabetes itself arise together, consistent with the hypothesis that they share a common antecedent.9 Furthermore, retinopathy and nephropathy may present in the absence of either overt clinical diabetes or IR.165 According to the mTOR-centric model, retinopathy and nephropathy as well as IR and beta-cell failure are complications of mTOR hyperactivation (Figure 4). In addition, IR causes a compensatory increase in insulin secretion that in turn may activate mTOR in the retina. Hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia further activate mTOR. Similarly, hyperglycemia may activate mTOR and cause metabolic syndrome and IR in type I diabetes.166 In type II diabetes, both IR and early complications may be manifestations of mTOR hyperactivation. Hyperactivated mTOR in fat/liver and in the retina may cause IR and retinopathy, respectively.

Consequences of sustained mTOR activation. In the liver, muscle and fat tissues, sustained mTOR activation causes systemic IR. In the beta cells, mTOR initially increases beta-cell function, causes beta-cell hypertrophy and adaptation to IR. Beta-cell hyperfunction and IR eventually may cause beta-cell failure and type II diabetes. In the retina and the kidney, hyperactivation of mTOR may lead to retinopathy and nephropathy, respectively

Conclusion for Endocrinologists

Rapamycin and other rapalogs (everolimus, temserolimus) are widely used in the clinic for almost two decades. Their clinical applications range from transplantation to cancer treatment. Rapamycin and other rapalogs have been used in children56 and pregnant women.167 There were no side effects of high-dose rapamycin in healthy volunteers.82 Even in chronic high-dose administration, rapalogs are generally well tolerated. Despite common misconception, rapamycin and other rapalogs prevent cancer and viral infections in organ-transplant patients.152, 168 They improve immune response in old animals.169 Rapamycin was used to treat insulinoma,170, 171 polycystic kidney disease,172 systemic sclerosis173 and prevention of atherosclerotic in-stent restenosis.130, 131, 132 Now is the turn of diabetic complications. As I discussed here, rapalogs can be considered for prevention of side effects of intensive insulin therapy, for reduction of doses of insulin, for prevention of diabetic complications and atherosclerosis, for prevention of beta-cell failure and for the treatment of lactate acidosis. For these applications, rapamycin may be used at low doses and short-term or intermittent schedules. In theory, treatment of type II diabetes with insulin, if needed, may especially benefit from a combination with short-term or low-dose rapamycin.

Conclusion for Gerontologists

It is commonly assumed that aging and diseases of aging are distinct processes and that aging merely renders organism vulnerable to diseases rather than causing them. Thus, aging is believed to be driven by accumulation of molecular damage. Age-related conditions and diseases, such as IR and diabetes, are not caused by accumulation of molecular damage.44 In fact, IR can be reversed by low-calorie diet, weight loss and metformin, without affecting putative molecular damage. Linking gerontology and diabetology, the hyperfunction theory suggests that aging is not caused by damage but instead is driven by signal transduction pathways, the same pathways that are involved in age-related diseases.44, 47, 174, 175 Age-related diseases are continuation and exacerbation of the aging process. For example, hyperactivation of nutrient-sensing pathways such as mTOR and PKC in hepatocytes, adipocytes, retinal and beta cells stimulates cellular functions and also cause feedback insulin/signal resistance. These hyperfunctions eventually may culminate in beta-cell failure (diabetes) and nephropathy as well as accelerate atherosclerosis. In turn these diseases may result in organ failure (renal and heart failure, for instance), leading to organismal death.46

Abbreviations

- HIF-1:

-

hypoxia-inducible factor-1

- IGF-1:

-

insulin-like growth factor 1

- IR:

-

insulin resistance

- mTOR:

-

mammalian target of rapamycin

- PKC:

-

protein kinase C

- S6K:

-

S6 kinase

- TNF:

-

tumor necrosis factor

- TOR:

-

target of rapamycin

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Kasuga M . Insulin resistance and pancreatic beta cell failure. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 1756–1760.

Girach A, Vignati L . Diabetic microvascular complications--can the presence of one predict the development of another. J Diabetes Complications 2006; 20: 228–237.

Harris MI, Klein R, Welborn TA, Knuiman MW . Onset of NIDDM occurs at least 4–7yr before clinical diagnosis. Diabetes Care 1992; 15: 815–819.

Colagiuri S, Lee CM, Wong TY, Balkau B, Shaw JE, Borch-Johnsen K . Glycemic thresholds for diabetes-specific retinopathy: implications for diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 145–150.

Ellis JD, Zvandasara T, Leese G, McAlpine R, Macewen CJ, Baines PS et al. Clues to duration of undiagnosed disease from retinopathy and maculopathy at diagnosis in type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95: 1229–1233.

Cohen JA, Jeffers BW, Faldut D, Marcoux M, Schrier RW . Risks for sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy and autonomic neuropathy in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM). Muscle Nerve 1998; 21: 72–80.

Singleton JR, Smith AG . Therapy insight: neurological complications of prediabetes. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2006; 2: 276–282.

Singleton JR, Smith AG . Neuropathy associated with prediabetes: what is new in 2007? Curr Diab Rep 2007; 7: 420–424.

Meigs JB, D'Agostino RBS, Nathan DM, Rifai N, Wilson PW . Longitudinal association of glycemia and microalbuminuria: the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 977–983.

Groop PH, Forsblom C, Thomas MC . Mechanisms of disease: pathway-selective insulin resistance and microvascular complications of diabetes. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2005; 1: 100–110.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The prevalence of retinopathy in impaired glucose tolerance and recent-onset diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabet Med 2007; 24: 137–144.

Wong TY, Mohamed Q, Klein R, Couper DJ . Do retinopathy signs in non-diabetic individuals predict the subsequent risk of diabetes? Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 301–303.

Singleton JR, Smith AG, Russell JW, Feldman EL . Microvascular complications of impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes 2003; 52: 2867–2873.

Wilson PW, Kannel WB . Obesity, diabetes, and risk of cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 2002; 11: 119–123.

Moskalets E, Galstyan G, Starostina E, Antsiferov M, Chantelau E . Association of blindness to intensification of glycemic control in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications 1994; 8: 45–50.

Chantelau E, Meyer-Schwickerath R, Klabe K . Downregulation of serum IGF-1 for treatment of early worsening of diabetic retinopathy: a long-term follow-up of two cases. Ophthalmologica 2010; 224: 243–246.

Agardh CD, Eckert B, Agardh E . Irreversible progression of severe retinopathy in young type I insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients after improved metabolic control. J Diabetes Complications 1992; 6: 96–100.

Henricsson M, Berntorp K, Berntorp E, Fernlund P, Sundkvist G . Progression of retinopathy after improved metabolic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Relation to IGF-1 and hemostatic variables. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 1944–1949.

Henricsson M, Janzon L, Groop L . Progression of retinopathy after change of treatment from oral antihyperglycemic agents to insulin in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1995; 18: 1571–1576.

Funatsu H, Yamashita H, Ohashi Y, Ishigaki T . Effect of rapid glycemic control on progression of diabetic retinopathy. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1992; 36: 356–367.

Gibbons CH, Freeman R . Treatment-induced diabetic neuropathy: a reversible painful autonomic neuropathy. Ann Neurol 2010; 67: 534–541.

Tremblay F, Marette A . Amino acid and insulin signaling via the mTOR/p70 S6 kinase pathway. A negative feedback mechanism leading to insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 38052–38060.

Hands SL, Proud CG, Wyttenbach A . mTOR’s role in ageing: protein synthesis or autophagy? Aging (Albany NY) 2009; 1: 586–597.

Cornu M, Albert V, Hall MN . mTOR in aging, metabolism, and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2013; 23: 53–62.

Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM . mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011; 12: 21–35.

Blagosklonny MV, Hall MN . Growth and aging: a common molecular mechanism. Aging 2009; 1: 357–362.

Leontieva OV, Geraldine M, Paszkiewicz GM, Blagosklonny MV . Mechanistic or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) may determine robustness in young male mice at the cost of accelerated aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 899–891.

Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV . Growth stimulation leads to cellular senescence when the cell cycle is blocked. Cell Cycle 2008; 7: 3355–3361.

Demidenko ZN, Korotchkina LG, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV . Paradoxical suppression of cellular senescence by p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 9660–9664.

Leontieva OV, Natarajan V, Demidenko ZN, Burdelya LG, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV . Hypoxia suppresses conversion from proliferative arrest to cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 13314–13318.

Dulic V . Be quiet and you'll keep young: does mTOR underlie p53 action in protecting against senescence by favoring quiescence? Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 3–4.

Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G . TP53 and MTOR crosstalk to regulate cellular senescence. Aging (Albany NY) 2010; 2: 535–537.

Leontieva OV, Lenzo F, Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV . Hyper-mitogenic drive coexists with mitotic incompetence in senescent cells. Cell Cycle 2012; 11: 4642–4649.

Leontieva OV, Demidenk ZN, Blagosklonny MV . MEK drives cyclin D1 hyperelevation during geroconversion. Cell Deth Diff 2013; 20: 1241–1249.

Hinojosa CA, Mgbemena V, Van Roekel S, Austad SN, Miller RA, Bose S et al. Enteric-delivered rapamycin enhances resistance of aged mice to pneumococcal pneumonia through reduced cellular senescence. Exp Gerontol 2012; 47: 958–965.

Halicka HD, Zhao H, Li J, Lee YS, Hsieh TC, Wu JM et al. Potential anti-aging agents suppress the level of constitutive mTOR- and DNA damage- signaling. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 952–965.

Iglesias-Bartolome R, Gutkind SJ . Exploiting the mTOR paradox for disease prevention. Oncotarget 2012; 3: 1061–1063.

Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G . The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013; 153: 1194–1217.

Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, van Deursen J, Campisi J, Kirkland JL . Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 966–972.

CoppŽ JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun Y, Mu–oz DP, Goldstein J et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol 2008; 6: 2853–2868.

Blagosklonny MV . Cell cycle arrest is not yet senescence, which is not just cell cycle arrest: terminology for TOR-driven aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 159–165.

Cahu J, Bustany S, Sola B . Senescence-associated secretory phenotype favors the emergence of cancer stem-like cells. Cell Death Dis 2012; 3: e446.

Tominaga-Yamanaka K, Abdelmohsen K, Martindale JL, Yang X, Taub DD, Gorospe M . NF90 coordinately represses the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 695–708.

Blagosklonny MV . Answering the ultimate question ‘what is the proximal cause of aging?’. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 861–877.

Blagosklonny MV . Why men age faster but reproduce longer than women: mTOR and evolutionary perspectives. Aging (Albany NY) 2010; 2: 265–273.

Blagosklonny MV . Prospective treatment of age-related diseases by slowing down aging. Am J Pathol 2012; 181: 1142–1146.

Blagosklonny MV . How to save Medicare: the anti-aging remedy. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 547–552.

Blagosklonny MV . Aging and immortality: quasi-programmed senescence and its pharmacologic inhibition. Cell Cycle 2006; 5: 2087–2102.

Blagosklonny MV . An anti-aging drug today: from senescence-promoting genes to anti-aging pill. Drug Disc Today 2007; 12: 218–224.

Tsang CK, Qi H, Liu LF, Zheng XFS . Targeting mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) for health and diseases. Drug Disc Today 2007; 12: 112–124.

Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M . mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature 2013; 493: 338–345.

Nair S, Ren J . Autophagy and cardiovascular aging: lesson learned from rapamycin. Cell Cycle 2012; 11: 2092–2099.

Williamson DL . Normalizing a hyperactive mTOR initiates muscle growth during obesity. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 83–84.

Blagosklonny MV . Rapamycin extends life- and health span because it slows aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2013; 5: 592–598.

Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogenous mice. Nature 2009; 460: 392–396.

Major P . Potential of mTOR inhibitors for the treatment of subependymal giant cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis complex. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 189–191.

Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Popovich IG, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML et al. Rapamycin extends maximal lifespan in cancer-prone mice. Am J Pathol 2010; 176: 2092–2097.

Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Popovich IG, Piskunova TS, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML et al. Rapamycin increases lifespan and inhibits spontaneous tumorigenesis in inbred female mice. Cell Cycle 2011; 10: 4230–4236.

Comas M, Toshkov I, Kuropatwinski KK, Chernova OB, Polinsky A, Blagosklonny MV et al. New nanoformulation of rapamycin Rapatar extends lifespan in homozygous p53-/- mice by delaying carcinogenesis. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 715–722.

Komarova EA, Antoch MP, Novototskaya LR, Chernova OB, Paszkiewicz G, Leontieva OV et al. Rapamycin extends lifespan and delays tumorigenesis in heterozygous p53+/− mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 709–714.

Levine AJ, Harris CR, Puzio-Kuter AM . The interfaces between signal transduction pathways: IGF-1/mTor, p53 and the Parkinson disease pathway. Oncotarget 2012; 3: 1301–1307.

Donehower LA . Rapamycin as longevity enhancer and cancer preventative agent in the context of p53 deficiency. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 660–661.

Halloran J, Hussong SA, Burbank R, Podlutskaya N, Fischer KE, Sloane LB et al. Chronic inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin by rapamycin modulates cognitive and non-cognitive components of behavior throughout lifespan in mice. Neuroscience 2012; 223: 102–113.

Wilkinson JE, Burmeister L, Brooks SV, Chan CC, Friedline S, Harrison DE et al. Rapamycin slows aging in mice. Aging Cell 2012; 11: 675–682.

Flynn JM, O'Leary MN, Zambataro CA, Academia EC, Presley MP, Garrett BJ et al. Late life rapamycin treatment reverses age-related heart dysfunction. Aging Cell 2013; 12: 851–862.

Kapahi P, Chen D, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Li PW, Thomas EL et al. With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab 2010; 11: 453–465.

Khanna A, Kapahi P . Rapamycin: killing two birds with one stone. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 1043–1044.

Longo VD, Fontana L . Intermittent supplementation with rapamycin as a dietary restriction mimetic. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 1039–1040.

Ye L, Widlund AL, Sims CA, Lamming DW, Guan Y, Davis JG et al. Rapamycin doses sufficient to extend lifespan do not compromise muscle mitochondrial content or endurance. Aging (Albany NY) 2013; 5: 539–550.

Kolosova NG, Vitovtov AO, Muraleva NA, Akulov AE, Stefanova NA, Blagosklonny MV . Rapamycin suppresses brain aging in senescence-accelerated OXYS rats. Aging (Albany NY) 2013; 5: 474–484.

Ueno M, Carvalheira JB, Tambascia RC, Bezerra RM, Amaral ME, Carneiro EM et al. Regulation of insulin signalling by hyperinsulinaemia: role of IRS-1/2 serine phosphorylation and the mTOR/p70 S6K pathway. Diabetologia 2005; 48: 506–518.

Shah OJ, Wang Z, Hunter T . Inappropriate activation of the TSC/Rheb/mTOR/S6K cassette induces IRS1/2 depletion, insulin resistance, and cell survival deficiencies. Curr Biol 2004; 14: 1650–1656.

Tzatsos A, Kandror KV . Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26: 63–76.

Khamzina L, Veilleux A, Bergeron S, Marette A . Increased activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in liver and skeletal muscle of obese rats: possible involvement in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 1473–1481.

Tremblay F, BržlŽ S, Hee UmS, Li Y, Masuda K, Roden M et al. Identification of IRS-1 Ser-1101 as a target of S6K1 in nutrient- and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 14056–14061.

Tremblay F, Krebs M, Dombrowski L, Brehm A, Bernroider E, Roth E et al. Overactivation of S6 kinase 1 as a cause of human insulin resistance during increased amino acid availability. Diabetes 2005; 54: 2674–2684.

Saha AK, Xu XJ, Balon TW, Brandon A, Kraegen EW, Ruderman NB . Insulin resistance due to nutrient excess: is it a consequence of AMPK downregulation? Cell Cycle 2011; 10: 3447–3451.

Barbour LA, McCurdy CE, Hernandez TL, Friedman JE . Chronically increased S6K1 is associated with impaired IRS1 signaling in skeletal muscle of GDM women with impaired glucose tolerance postpartum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 1431–1441.

Hsu PP, Kang SA, Rameseder J, Zhang Y, Ottina KA, Lim D et al. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science 2011; 332: 1317–1322.

Yu Y, Yoon SO, Poulogiannis G, Yang Q, Ma XM, Villen J et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science 2011; 332: 1322–1326.

Korsheninnikova E, van der Zon GC, Voshol PJ, Janssen GM, Havekes LM, Grefhorst A et al. Sustained activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin nutrient sensing pathway is associated with hepatic insulin resistance, but not with steatosis, in mice. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 3049–3057.

Krebs M, Brunmair B, Brehm A, Artwohl M, Szendroedi J, Nowotny P et al. The mammalian target of rapamycin pathway regulates nutrient-sensitive glucose uptake in man. Diabetes 2007; 56: 1600–1607.

Ozes ON, Akca H, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Maehama T, Dixon JE et al. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR pathway mediates and PTEN antagonizes tumor necrosis factor inhibition of insulin signaling through insulin receptor substrate-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 4640–4645.

Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A . Inflammaging: disturbed interplay between autophagy and inflammasomes. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 166–175.

Cai D, Liu T . Inflammatory cause of metabolic syndrome via brain stress and NF-kappaB. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 98–115.

Blagosklonny MV . Calorie restriction: decelerating mTOR-driven aging from cells to organisms (including humans). Cell Cycle 2010; 9: 683–688.

Glynn EL, Lujan HL, Kramer VJ, Drummond MJ, DiCarlo SE, Rasmussen BB . A chronic increase in physical activity inhibits fed-state mTOR/S6K1 signaling and reduces IRS-1 serine phosphorylation in rat skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2008; 33: 93–101.

Poulaki V, Qin W, Joussen AM, Hurlbut P, Wiegand SJ, Rudge J et al. Acute intensive insulin therapy exacerbates diabetic blood-retinal barrier breakdown via hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and VEGF. J Clin Invest 2002; 109: 805–815.

Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, Keyt BA, Jampel HD, Shah ST et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 1480–1487.

Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16: 4604–4613.

Vinores SA, Xiao WH, Aslam S, Shen J, Oshima Y, Nambu H et al. Implication of the hypoxia response element of the Vegf promoter in mouse models of retinal and choroidal neovascularization, but not retinal vascular development. J Cell Physiol 2006; 206: 749–758.

Poulaki V, Joussen AM, Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Iliaki EF, Adamis AP . Insulin-like growth factor-I plays a pathogenetic role in diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol 2004; 165: 457–469.

Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Semenza GL, Van Obberghen E . Insulin stimulates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/target of rapamycin-dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 27975–27981.

Slomiany MG, Rosenzweig SA . IGF-1-induced VEGF and IGFBP-3 secretion correlates with increased HIF-1 alpha expression and activity in retinal pigment epithelial cell line D407. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004; 45: 2838–2847.

Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV . The purpose of the HIF-1/PHD feedback loop: to limit mTOR-induced HIF-1alpha. Cell Cycle 2011; 10: 1557–1562.

Smith LE, Shen W, Perruzzi C, Soker S, Kinose F, Xu X et al. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent retinal neovascularization by insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Nat Med 1999; 5: 1390–1395.

Lu M, Amano S, Miyamoto K, Garland R, Keough K, Qin W et al. Insulin-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999; 40: 3281–3286.

Chantelau E, Frystyk J . Progression of diabetic retinopathy during improved metabolic control may be treated with reduced insulin dosage and/or somatostatin analogue administration -- a case report. Growth Horm IGF Res 2005; 15: 130–135.

Demidenko ZN, Zubova SG, Bukreeva EI, Pospelov VA, Pospelova TV, Blagosklonny MV . Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 2009; 8: 1888–1895.

Dejneka NS, Kuroki AM, Fosnot J, Tang W, Tolentino MJ, Bennett J . Systemic rapamycin inhibits retinal and choroidal neovascularization in mice. Mol Vis 2004; 10: 964–972.

Kolosova NG, Muraleva NA, Zhdankina AA, Stefanova NA, Fursova AZ, Blagosklonny MV . Prevention of age-related macular degeneration-like retinopathy by rapamycin in rats. Am J Pathol 2012; 181: 472–477.

Zheng XF . Chemoprevention of age-related macular regeneration (AMD) with rapamycin. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 375–376.

Krishnadev N, Forooghian F, Cukras C, Wong W, Saligan L, Chew EY et al. Subconjunctival sirolimus in the treatment of diabetic macular edema. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011; 249: 1627–1633.

Lloberas N, Cruzado JM, Franquesa M, Herrero-Fresneda I, Torras J, Alperovich G et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway blockade slows progression of diabetic kidney disease in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 1395–1404.

Sakaguchi M, Isono M, Isshiki K, Sugimoto T, Koya D, Kashiwagi A . Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin attenuates renal hypertrophy in the early diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 340: 296–301.

Yang Y, Wang J, Qin L, Shou Z, Zhao J, Wang H et al. Rapamycin prevents early steps of the development of diabetic nephropathy in rats. Am J Nephrol 2007; 27: 495–502.

Rhodes CJ . Type 2 diabetes-a matter of beta-cell life and death? Science 2005; 307: 380–384.

Mooijaart SP, van Heemst D, Noordam R, Rozing MP, Wijsman CA, de Craen AJ et al. Polymorphisms associated with type 2 diabetes in familial longevity: the Leiden Longevity Study. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 55–62.

Newman AB, Glynn NW, Taylor CA, Sebastiani P, Perls TT, Mayeux R et al. Health and function of participants in the Long Life Family Study: a comparison with other cohorts. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 63–76.

Leibowitz G, Bachar E, Shaked M, Sinai A, Ketzinel-Gilad M, Cerasi E et al. Glucose regulation of beta-cell stress in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 12 (Suppl 2): 66–75.

Guevara-Aguirre J, Balasubramanian P, Guevara-Aguirre M, Wei M, Madia F, Cheng CW et al. Growth hormone receptor deficiency is associated with a major reduction in pro-aging signaling, cancer, and diabetes in humans. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 70ra13.

Gunasekaran U, Gannon M . Type 2 diabetes and the aging pancreatic beta cell. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 565–575.

Tacutu R, Budovsky A, Yanai H, Fraifeld VE . Molecular links between cellular senescence, longevity and age-related diseases—a systems biology perspective. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 1178–1191.

Shigeyama Y, Kobayashi T, Kido Y, Hashimoto N, Asahara S, Matsuda T et al. Biphasic response of pancreatic beta-cell mass to ablation of tuberous sclerosis complex 2 in mice. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28: 2971–2979.

Leontieva OV, Paszkiewicz G, Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV . Resveratrol potentiates rapamycin to prevent hyperinsulinemia and obesity in male mice on high fat diet. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e472.

Chen J, Huang XF . Mechanism for the synergistic effect of rapamycin and resveratrol on hyperinsulinemia may involve the activation of protein kinase B. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4: e680.

Briaud I, Dickson LM, Lingohr MK, McCuaig JF, Lawrence JC, Rhodes CJ . Insulin receptor substrate-2 proteasomal degradation mediated by a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-induced negative feedback down-regulates protein kinase B-mediated signaling pathway in beta-cells. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 2282–2293.

White MF . IRS proteins and the common path to diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002; 283: E413–E422.

Bachar E, Ariav Y, Ketzinel-Gilad M, Cerasi E, Kaiser N, Leibowitz G . Glucose amplifies fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells via activation of mTORC1. PLoS One 2009; 4: e4954.

Allagnat F, Cunha D, Moore F, Vanderwinden JM, Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK . Mcl-1 downregulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines and palmitate is an early event contributing to beta-cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2011; 18: 328–337.

Allagnat F, Fukaya M, Nogueira TC, Delaroche D, Welsh N, Marselli L et al. C/EBP homologous protein contributes to cytokine-induced pro-inflammatory responses and apoptosis in beta-cells. Cell Death Differ 2012; 19: 1836–1846.

Yang SB, Lee HY, Young DM, Tien AC, Rowson-Baldwin A, Shu YY et al. Rapamycin induces glucose intolerance in mice by reducing islet mass, insulin content, and insulin sensitivity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011; 90: 575–585.

Velazquez-Garcia S, Valle S, Rosa TC, Takane KK, Demirci C, Alvarez-Perez JC et al. Activation of protein kinase C-zeta in pancreatic beta-cells in vivo improves glucose tolerance and induces beta-cell expansion via mTOR activation. Diabetes 2011; 60: 2546–2559.

Elghazi L, Balcazar N, Blandino-Rosano M, Cras-Meneur C, Fatrai S, Gould AP et al. Decreased IRS signaling impairs beta-cell cycle progression and survival in transgenic mice overexpressing S6K in beta-cells. Diabetes 2010; 59: 2390–2399.

Blagosklonny MV . Rapamycin-induced glucose intolerance: hunger or starvation diabetes. Cell Cycle 2011; 10: 4217–4224.

Blagosklonny MV . Once again on rapamycin-induced insulin resistance and longevity: despite of or owing to. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 350–358.

Unger RH, Grundy S . Hyperglycaemia as an inducer as well as a consequence of impaired islet cell function and insulin resistance: implications for the management of diabetes. Diabetologia 1985; 28: 119–121.

Vuorinen-Markkola H, Koivisto VA, Yki-Jarvinen H . Mechanisms of hyperglycemia-induced insulin resistance in whole body and skeletal muscle of type I diabetic patients. Diabetes 1992; 41: 571–580.

Yki-Jarvinen H . Acute and chronic effects of hyperglycaemia on glucose metabolism: implications for the development of new therapies. Diabet Med 1997; 14 (Suppl 3): S32–S37.

Chaves AJ, Sousa AG, Mattos LA, Abizaid A, Feres F, Staico R et al. Pilot study with an intensified oral sirolimus regimen for the prevention of in-stent restenosis in de novo lesions: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2005; 66: 535–540.

Rodriguez AE, Alemparte MR, Vigo CF, Pereira CF, Llaurado C, Russo M et al. Pilot study of oral rapamycin to prevent restenosis in patients undergoing coronary stent therapy: Argentina Single-Center Study (ORAR Trial). J Invasive Cardiol 2003; 15: 581–584.

Guarda E, Marchant E, Fajuri A, Martinez A, Moran S, Mendez M et al. Oral rapamycin to prevent human coronary stent restenosis: a pilot study. Am Heart J 2004; 148: e9.

Blagosklonny MV . Common drugs and treatments for cancer and age-related diseases: revitalizing answers to NCI's provocative questions. Oncotarget 2012; 3: 1711–1724.

Blagosklonny MV . NCI's provocative questions on cancer: some answers to ignite discussion. Oncotarget 2011; 2: 1352–1367.

Mercier I, Camacho J, Titchen K, Gonzales DM, Quann K, Bryant KG et al. Caveolin-1 and accelerated host aging in the breast tumor microenvironment: chemoprevention with rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor and anti-aging drug. Am J Pathol 2012; 181: 278–293.

Leontieva OV, Blagosklonny MV . Yeast-like chronological senescence in mammalian cells: phenomenon, mechanism and pharmacological suppression. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 1078–1091.

Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS et al. If started early in life, metformin treatment increases life span and postpones tumors in female SHR mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 148–157.

Berstein LM . Metformin in obesity, cancer and aging: addressing controversies. Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 320–329.

Del Barco S, Vazquez-Martin A, Cufi S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Bosch-Barrera J, Joven J et al. Metformin: multi-faceted protection against cancer. Oncotarget 2011; 2: 896–917.

Fierz Y, Novosyadlyy R, Vijayakumar A, Yakar S, LeRoith D . Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition abrogates insulin-mediated mammary tumor progression in type 2 diabetes. Endocr Relat Cancer 2010; 17: 941–951.

Tomic T, Botton T, Cerezo M, Robert G, Luciano F, Puissant A et al. Metformin inhibits melanoma development through autophagy and apoptosis mechanisms. Cell Death Dis 2011; 2: e199.

Shi WY, Xiao D, Wang L, Dong LH, Yan ZX, Shen ZX et al. Therapeutic metformin/AMPK activation blocked lymphoma cell growth via inhibition of mTOR pathway and induction of autophagy. Cell Death Dis 2012; 3: e275.

Liu Y, Huang Y, Wang Z, Li X, Louie A, Wei G et al. Temporal mTOR inhibition protects Fbxw7-deficient mice from radiation-induced tumor development. Aging (Albany NY) 2013; 5: 111–119.

Menendez JA, Cufi S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vellon L, Joven J, Vazquez-Martin A . Gerosuppressant metformin: less is more. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 348–362.

Moiseeva O, Deschenes-Simard X, Pollak M, Ferbeyre G . Metformin, aging and cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2013; 5: 330–331.

Lewis DA, Travers JB, Machado C, Somani AK, Spandau DF . Reversing the aging stromal phenotype prevents carcinoma initiation. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 407–416.

Floc'h N, Abate-Shen C . The promise of dual targeting Akt/mTOR signaling in lethal prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2012; 3: 1483–1484.

Garrett JT, Chakrabarty A, Arteaga CL . Will PI3K pathway inhibitors be effective as single agents in patients with cancer? Oncotarget 2011; 2: 1314–1321.

Janku F, Wheler JJ, Naing A, Stepanek VM, Falchook GS, Fu S et al. PIK3CA mutations in advanced cancers: characteristics and outcomes. Oncotarget 2012; 3: 1566–1575.

Blagosklonny MV . Molecular damage in cancer: an argument for mTOR-driven aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2011; 3: 1130–1141.

Blagosklonny MV . Tumor suppression by p53 without apoptosis and senescence: conundrum or rapalog-like gerosuppression? Aging (Albany NY) 2012; 4: 450–455.

Blagosklonny MV . Rapalogs in cancer prevention: anti-aging or anticancer? Cancer Biol Ther 2012; 13: 1349–1354.

Shaw RJ, Lamia KA, Vasquez D, Koo SH, Bardeesy N, Depinho RA et al. The kinase LKB1 mediates glucose homeostasis in liver and therapeutic effects of metformin. Science 2005; 310: 1642–1646.

He G, Sung YM, Digiovanni J, Fischer SM . Thiazolidinediones inhibit insulin-like growth factor-i-induced activation of p70S6 kinase and suppress insulin-like growth factor-I tumor-promoting activity. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 1873–1878.

Fang Y, Bartke A . Prolonged rapamycin treatment led to beneficial metabolic switch. Aging (Albany NY) 2013; 5: 328–329.

Deblon N, Bourgoin L, Veyrat-Durebex C, Peyrou M, Vinciguerra M, Caillon A et al. Chronic mTOR inhibition by rapamycin induces muscle insulin resistance despite weight loss in rats. Br J Pharmacol 165: 2325–2340.

Houde VP, Brule S, Festuccia WT, Blanchard PG, Bellmann K, Deshaies Y et al. Chronic rapamycin treatment causes glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia by upregulating hepatic gluconeogenesis and impairing lipid deposition in adipose tissue. Diabetes 2010; 59: 1338–1348.

Yang SB, Lee HY, Young DM, Tien AC, Rowson-Baldwin A, Shu YY et al. Rapamycin induces glucose intolerance in mice by reducing islet mass, insulin content, and insulin sensitivity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012; 90: 575–585.

Chang GR, Wu YY, Chiu YS, Chen WY, Liao JW, Hsu HM et al. Long-term administration of rapamycin reduces adiposity, but impairs glucose tolerance in high-fat diet-fed KK/HlJ mice. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2009; 105: 188–198.

Lamming DW, Ye L, Katajisto P, Goncalves MD, Saitoh M, Stevens DM et al. Rapamycin-induced insulin resistance is mediated by mTORC2 loss and uncoupled from longevity. Science 2012; 335: 1638–1643.

Lamming DW, Ye L, Astle CM, Baur JA, Sabatini DM, Harrison DE . Young and old genetically heterogeneous HET3 mice on a rapamycin diet are glucose intolerant but insulin sensitive. Aging Cell 2013; 12: 712–718.

Blagosklonny MV . Linking calorie restriction to longevity through sirtuins and autophagy: any role for TOR. Cell Death Dis 2010; 1: e12.

Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM . Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 2006; 444: 840–846.

Mordier S, Iynedjian PB . Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and insulin resistance induced by palmitate in hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 362: 206–211.

Chan JY, Cole E, Hanna AK . Diabetic nephropathy and proliferative retinopathy with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 1985; 8: 385–390.

Thorn LM, Forsblom C, Fagerudd J, Thomas MC, Pettersson-Fernholm K, Saraheimo M et al. Metabolic syndrome in type 1 diabetes: association with diabetic nephropathy and glycemic control (the FinnDiane study). Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2019–2024.

Sifontis NM, Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, Lavelanet AF, Moritz MJ, Armenti VT . Pregnancy outcomes in solid organ transplant recipients with exposure to mycophenolate mofetil or sirolimus. Transplantation 2006; 82: 1698–1702.

Ozaki KS, Camara NO, Nogueira E, Pereira MG, Granato C, Melaragno C et al. The use of sirolimus in ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infections in renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2007; 21: 675–680.

Araki K, Ellebedy AH, Ahmed R . TOR in the immune system. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2011; 23: 707–715.

Kulke MH, Bergsland EK, Yao JC . Glycemic control in patients with insulinoma treated with everolimus. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 195–197.

Bourcier ME, Sherrod A, DiGuardo M, Vinik AI . Successful control of intractable hypoglycemia using rapamycin in an 86-year-old man with a pancreatic insulin-secreting islet cell tumor and metastases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 3157–3162.

Soliman AR, Ismail E, Zamil S, Lotfy A . Sirolimus therapy for patients with adult polycystic kidney disease: a pilot study. Transplant Proc 2009; 41: 3639–3641.

Su TI, Khanna D, Furst DE, Danovitch G, Burger C, Maranian P et al. Rapamycin versus methotrexate in early diffuse systemic sclerosis: results from a randomized, single-blind pilot study. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 3821–3830.

Gems DH, de la Guardia YI . Alternative perspectives on aging in C. elegans: reactive oxygen species or hyperfunction? Antioxid Redox Signal 2013; 19: 321–329.

Gems D, Partridge L . Genetics of longevity in model organisms: debates and paradigm shifts. Annu Rev Physiol 2013; 75: 621–644.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author is a consultant of Tartis-Aging Inc. (USA).

Additional information

Edited by G Melino

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Blagosklonny, M. TOR-centric view on insulin resistance and diabetic complications: perspective for endocrinologists and gerontologists. Cell Death Dis 4, e964 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.506

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.506

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The prognostic outcome of ‘type 2 diabetes mellitus and breast cancer’ association pivots on hypoxia-hyperglycemia axis

Cancer Cell International (2021)

-

A spotlight on underlying the mechanism of AMPK in diabetes complications

Inflammation Research (2021)

-

Type 2 diabetes – unmet need, unresolved pathogenesis, mTORC1-centric paradigm

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2020)

-

Fasting and rapamycin: diabetes versus benevolent glucose intolerance

Cell Death & Disease (2019)

-

Mitochondrial fusion regulates lipid homeostasis and stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila testis

Nature Cell Biology (2019)