Abstract

Background:

Although family history is well established to be a risk factor for developing colorectal cancer (CRC), much less is known about its impact on patient survival. This study aimed to link CRC patient data from the National Study of Colorectal Cancer Genetics (NSCCG) to the National Cancer Data Repository (NCDR) to examine the relationship between family history and the characteristics and outcomes of CRC.

Methods:

All eligible NSCCG patients underwent a matching process to the NCDR using combinations of their personal identifiers. The characteristics and survival of CRC patients with and without a family history of CRC were compared.

Results:

Of the 10 937 NSCCG patients eligible to be matched into the NCDR, 10 782 (98.6%) could be fully linked. There were no significant differences between those with and without a family history of CRC (defined as having at least one affected first-degree relative) in terms of age, sex, tumour stage at diagnosis, presence of multiple cancers, mode of presentation to hospital and surgical management, although patients with familial CRC were more likely to have right-sided tumours (P<0.01). The survival of patients with familial CRC was significantly better than those with sporadic CRC (HR 0.89, 95%CI: 0.81–0.98, P=0.02).

Conclusion:

We have demonstrated that it is possible to robustly match patients recruited into the NSCCG into the NCDR and, by using this record linkage, enable genetic data to be related to CRC phenotype, clinical management and outcome. This study provides evidence that a family history of CRC is associated with better survival after a diagnosis of CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the United Kingdom, affecting ∼40 000 individuals and accounting for ∼16 000 cancer-related deaths each year (Cancer Research UK, 2012). Family history is recognised to be a risk factor for CRC, with relatives of CRC cases having a two- to three-fold increased risk (Johns and Houlston, 2001). Although part of the familial risk can be ascribed to a number of inherited cancer syndromes, most of the heritable risk remains unexplained (Aaltonen et al, 2007).

Significant research effort has been focussed on extending our understanding of inherited susceptibility to CRC and the biological basis of genetic risk factors. Much of this research has been contingent on the development of large case series for gene discovery efforts. For example, within the United Kingdom, the National Study of Colorectal Cancer Genetics (NSCCG) (Penegar et al, 2007; Houlston et al, 2012) has collected DNA and clinicopathological data from >25 000 patients with histologically proven CRC.

As a potential prognostic factor, the concept of germline variation imparting interindividual variability in tumour development, progression and metastasis is receiving increasing attention (Kune et al, 1992; Registry Committee and Japanese Research Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum, 1993; Bass et al, 2008; Chan et al, 2008; Zell et al, 2008; Birgisson et al, 2009; Kao et al, 2009; Kirchoff et al, 2012). Some studies have demonstrated survival advantage for patients with familial CRC (Registry Committee and Japanese Research Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum, 1993; Chan JA et al, 2008; Zell et al, 2008; Birgisson et al, 2009; Kirchoff et al, 2012) but this finding has not been universal (Kune et al, 1992; Bass et al, 2008; Kirchoff et al, 2012).

The ability to relate detailed genetic information to management and outcome in large case series is highly desirable but difficult to achieve. Within the United Kingdom, a potential solution is the National Cancer Data Repository (NCDR) (National Cancer Intelligence Network, 2012) that contains population-based routine administrative National Health Service (NHS) data sets linked together to enable the pathways of all diagnosed with cancer in England to be tracked from diagnosis to cure or death. Inclusion of genetic information captured by studies such as the NSCCG into this resource offers the prospect of being able to relate genotype to phenotype, management and outcome data on a large scale. We sought to assess the feasibility of such a strategy and have investigated the relationship between a family history of CRC and patient outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and record linkage

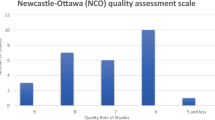

Information on CRC patients recruited before September 2011 was obtained from the NSCCG database. As the study period and recruitment area of the NSCCG are not fully compatible with the data held in the NCDR, a number of exclusions were made (Figure 1). First, the NSCCG recruits CRC patients from across the United Kingdom, whereas the NCDR is currently limited to England. Individuals residing outside England were, therefore, excluded. Furthermore, at the time of analysis, the NCDR was only complete for cancers diagnosed between 1990 and 2008, and hence cases recruited into the NSCCG after 2008 were also excluded. The remaining cases were linked to the NCDR using all or combinations of the identifiers of name, NHS number, date of birth, sex, hospital of management/histology, hospital number and postcode at diagnosis.

The NCDR holds information about all tumours diagnosed in England, allowing matching of NSCCG cases diagnosed with multiple cancers to be matched to multiple records. For NSCCG patients with multiple CRCs, the first diagnosed was considered as the index tumour and information about this cancer was used in analyses. If an NSCCG patient was linked to the NCDR but not to a CRC record, then that patient was only deemed to match if there was evidence that the tumour recorded by the registry was, indeed, relevant to why the individual had been recruited to the NSCCG (e.g., the registry had recorded an anal tumour rather than a colorectal tumour). NSCCG participants who were linked to any other tumour sites were excluded.

Age at diagnosis was derived from NCDR based on the date of diagnosis of the index tumour. Colonic tumours in the appendix, caecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure and transverse colon (ICD10 C180-C184) were considered to be right-sided tumours, whereas those at the splenic flexure and in the descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectosigmoid junction were considered to be left-sided tumours (ICD10 C185-C187 and C19). Tumours overlapping two sites in the colon (C188), with no site specified (C189), and all the noncolorectal cancer matches (excluding anal cancers) were included in a category called colon not otherwise specified (NOS). Rectal and anal tumours (ICD10 C20-C21) were assigned to a rectal cancer category.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 11.0 (State College, TX, USA). A P-value of 0.05 (two sided) was considered to be significant. Differences in patient characteristics between groups were assessed using χ2 and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Survival was calculated from the date of recruitment to the NSCCG to date of death or when censored (30 June 2010). Kaplan–Meier graphs, log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate the relationship between family history and survival.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Of the 21 223 CRC patients recruited to the NSCCG, 10 937 (51.7%) were eligible for matching and, overall, 10 782 (98.6%) were matched to tumours considered eligible (Figure 1) and they form the basis of the cohort used for comparative analyses.

Of this population, 1697 (15.7%) reported on their NSCCG recruitment questionnaire a family history of the disease (defined as a first-degree relative (parent/sibling/offspring) with a diagnosis of CRC). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, Dukes’ stage, presence of multiple cancers, comorbidity, mode of presentation to hospital and surgical management (Table 1). A higher proportion of patients with familial CRC, however, had right-sided disease (P<0.01; Table 1).

Figure 2 shows that the overall 5-year survival for familial CRC patients was significantly better than those with sporadic disease, and the survival advantage was correlated to the number of affected family members, notably in the small number of individuals (n=211) with two or more family members also diagnosed with CRC. This effect remained in a case-mix adjusted Cox proportional hazards model (Table 2a), with this group having a 25% reduction in their risk of death compared with those with sporadic disease (HR=0.75, 95% CI: 0.57–0.98, P=0.04). A stronger effect was observed when the effect of any family member having a history of colorectal cancer was examined (Table 2b). In this analysis, those with a family history had an 11% reduction in the risk of death compared with those with no family history (HR=0.89, 95% CI: 0.81–0.98, P=0.02).

The basis of a survival advantage associated with familial CRC is unclear. It is possible that a family history of the disease may heighten awareness of CRC in family members, hence leading to earlier detection and, thus, better prognosis. In our study, however, stage at diagnosis and the proportion of cases presenting as an emergency was similar across family history groups and the survival difference persisted after adjusting for case mix. These observations suggest that the difference in survival afforded in relationship to familial CRC was not simply a consequence of lead-time bias.

Our study also showed that a high proportion of individuals with a family history of CRC had right-sided tumours. This association is well recognised with right-sided tumours tending to arise because of deficient mismatch repair mechanisms that are linked to improved prognosis (Gryfe et al, 2000; Samowitz et al, 2001; Ricciardiello et al, 2003). As there is evidence that constitutional genotype influences response to chemotherapy (notably with respect to MMR status) and as family history is reflective of inherited genetic susceptibility, it is entirely plausible that the association between family history and better prognosis is reflective of an overrepresentation of MMR and polymerase gene defects affecting responsiveness. Our initial linkage has permitted this possibility to be addressed and further work will be undertaken to investigate this issue.

A limitation of the present study is that it has relied on self-reported family history and the accuracy and completeness of this information could vary for many reasons. As the NCDR contains information on all cancers diagnosed in England, future linkages should make it possible to eliminate any inaccuracy by verifying the accuracy of the histories provided.

The routine data that the NCDR is composed of may also limit the study. For example, it was not possible to match all the NSCCG patients into the NCDR as the resource is currently confined to patients diagnosed with cancer in England. Also, although a small minority of the cases who should have matched into the NCDR could not be linked, others did not link to CRC registrations. These failures were unusual but, nonetheless, an issue. They may be because of missed registrations, incorrect coding of cancer or inaccurate or incomplete sets of identifiers preventing linkage. Similarly, a number of individuals could not be linked because of the temporality of the data available in the NCDR. Both the scope of the NCDR and the time lag in the collection of the data it is composed of are being actively addressed and this should enable a much larger cohort of individuals from NSCCG to be linked.

Accepting these caveats we have shown that it is possible to robustly match patients recruited to the NSCCG into the NCDR and, using these data, demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between family history of CRC and better clinical outcome. Moreover, the linkage illustrates the potential of using routine data to relate genotype to management and outcome data and enhance our understanding of the processes underlying both the development and progression of CRC. The growing amount of data related to prognosis (including detailed pathology, chemotherapy and radiotherapy data) being captured by the NCDR will also enable these analyses to be appropriately adjusted to robustly delineate the true effect of genetic variations on prognosis. Many chemotherapy drugs and treatments are being developed that target subgroups of patients with specific genetic mutations (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009). Significant resource is being invested in developing such treatments, but very little is known about their use and effectiveness at a population level. Linking genetic data to the management and outcome data in the NCDR offers enormous scope to increase this evidence base.

References

Aaltonen LA, Johns LE, Jarvinen H, Mecklin JP, Houlston RS (2007) Explaining the familial colorectal cancer risk associated with mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient and MMR-stable tumours. Clin Cancer Res 13 (1): 356–361

Bass AJ, Meyerhardt JA, Chan JA, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS (2008) Family history and survivalafter colorectal cancer diagnosis. Cancer 112: 1222–1229

Birgisson H, Ghanipour A, Smedh K, Pahlman L, Glimelius B (2009) The correlation between a family histroy of colorectal cancer and survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Fam Cancer 8: 555–561

Cancer Research UK. Cancer Stats. 2012. Available at http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/bowel/

Chan JA, Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Thomas J, Schaefer P, Whittom R, Hantel A, Goldberg RM, Warren RS, Bertagnolli M, Fuchs CS (2008) Association of family history with cancer recurrence and survival among patients with stage III colon cancer. J Am Med Assoc 299 (21): 2515–2523

Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ETK, Aronson MD, Holowaty EJ, Bull SB, Redston M, Gallinger S (2000) Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patient with colorectal cancer. N Eng J Med 342 (2): 69–77

Houlston R, Peto J, Gray R (2012) National Study of Colorectal Cancer Genetics Protocol. Available at http://www.icr.ac.uk/research/team_leaders/Houlston_Richard/Houlston_Richard_RES/NSCCG/23438.pdf

Johns LE, Houlston RS (2001) A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol 96 (10): 2992–3003

Kao PS, Lin JK, Wang HS, Yang SH, Jiang JK, Chen WS, Lin TC, Li AF, Liang WY (2009) The impact of family history on the outcome of patients with colorectal cancer in a veterans' hospital. Int J Colorectal Dis 24 (11): 1249–1254

Kirchoff AC, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Nichols HB, Hampton JM (2012) Family history and colorectal cancer survival in women. Fam Cancer 7 (4): 287–292

Kune GA, Kune S, Watson LF (1992) The effect of family history of cancer, religion, parity and migrant status on survival in colorectal cancer. Data from the Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. Eur J Cancer 28A: 1484–1487

National Cancer Intelligence Network (2012) National Cancer Data Repository. Available at http://www.ncin.org.uk/collecting_and_using_data/national_cancer_data_repository/default.aspx

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) Cetuximab for the First Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence: London

Penegar S, Wood W, Lubbe S, Chandler I, Broderick P, Papaemmanuil E, Sellick G, Gray R, Peto J, Houlston R (2007) National study of colorectal cancer genetics. Br J Cancer 97: 1305–1309

Registry Committee and Japanese Research Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (1993) Clinical and pathological analyses of patients with a family history of colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 23: 342–349

Ricciardiello L, Goel A, Mantovani V, Fiorini T, Fossi S, Chang DK, Lunedei V, Pozzato P, Zagari RM, Luca LD, Martinelli GN, Roda E, Boland CR, Bazzoli F (2003) Frequent loss of hMLH1 by promoter hypermethylation leads to microsatellite instability in adenomatous polyps of patients with a single first-degree member affected by colon cancer. Cancer Res 63: 787–792

Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Ma KN, Schaffer D, Coleman LW, Leppert M, Slattery ML (2001) Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon cancer is associated with an improved prognosis at the population level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10: 917–923

Zell JA, Honda J, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H (2008) Survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis is associated with colorectal cancer family history. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17 (11): 3134–3140 (2008)

Acknowledgements

This paper is a contribution from the National Cancer Intelligence Network (www.ncin.org.uk) and the English registries (www.ukacr.org.uk). It is based on the information collected and quality assured by the regional cancer registries in England, specifically the Eastern Cancer Registration and Information Centre (Jem Rashbass), the Northern and Yorkshire Cancer Registry and Information Service (John Wilkinson and Brian Ferguson), the North West Cancer Intelligence Service (Tony Moran), the Oxford Cancer Intelligence Unit (Monica Roche), the South West Cancer Intelligence Service (Julia Verne), the Thames Cancer Registry (Elizabeth Davies), the Trent Cancer Registry (David Meechan) and the West Midlands Cancer Intelligence Unit (Gill Lawrence). We are grateful to all patients and their clinicians who have participated in the National Study of Colorectal Cancer Genetics (NSCCG). Finally, support from the National Cancer Research Network (NCRN) to the NSCCG is acknowledged. While undertaking this work, Eva Morris was funded by the Cancer Research UK Bobby Moore Fund (C23434/A9805), Phil Quirke by Yorkshire Cancer Research (L354PA) and Tim Bishop by Cancer Research UK (C588/A10589). Paul Finan was supported by the Leeds Cancer Research UK Centre. The National Study of Colorectal Cancer Genetics has been supported by grants from Cancer Research UK Bobby Moore Fund (C1298/A8362), CORE and the European Union Framework 6 awarded to Richard Houlston.

Author contributions

Steve Penegar, Richard Houlston, Eva Morris, Louise Whitehouse, Phil Quirke, Tim Bishop and John Wilkinson were instrumental in accessing and managing the data upon which this study is based. Louise Whitehouse, Eva Morris, Phil Quirke and Paul Finan produced clinically sound algorithms to extract data from the NCDR for this study and Eva Morris was responsible for its statistical analysis. Interpretation of the results was undertaken by Richard Houlston, Steve Penegar, Tim Bishop, Phil Quirke, Paul Finan, Eva Morris and John Wilkinson. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the paper and all authors approved the final version.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Morris, E., Penegar, S., Whitehouse, L. et al. A retrospective observational study of the relationship between family history and survival from colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 108, 1502–1507 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.91

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.91

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prognostic and Diagnostic Values of miR-506 and SPON 1 in Colorectal Cancer with Clinicopathological Considerations

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2021)

-

Family History of Cancer as Potential Prognostic Factor in Stage III Colorectal Cancer: a Retrospective Monoinstitutional Study

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2020)

-

Survival in familial colorectal cancer: a Danish cohort study

Familial Cancer (2015)

-

Prognostic impact of family history in southern Chinese patients with undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma

British Journal of Cancer (2013)