Abstract

The focal point of this paper is the transition from drug use to drug dependence. We present new evidence on risk for starting to use marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, as well as risks for progression from first drug use to the onset of drug dependence, separately for each of these drugs. Data from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) were analyzed. The NCS had a representative sample of the United States population ages 15–54 years (n = 8,098). Survival analysis techniques were used to provide age- and time-specific risk estimates of initiating use of marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, as well as of becoming dependent on each drug. With respect to risk of initiating use, estimated peak values for alcohol and marijuana were found at age 18, about two years earlier than the later peak in risk of initiating cocaine use. With respect to risk of meeting criteria for the clinical dependence syndrome, estimated peak values for alcohol and marijuana were found at age 17–18. Peak values for cocaine dependence were found at age 23–25. Once use began, cocaine dependence emerged early and more explosively, with an estimated 5–6% of cocaine users becoming cocaine dependent in the first year of use. Most of the observed cases of cocaine dependence met criteria for dependence within three years after initial cocaine use. Whereas some 15–16% of cocaine users had developed cocaine dependence within 10 years of first cocaine use, the corresponding values were about 8% for marijuana users, and 12–13% for alcohol users. The most novel findings of this study document a noteworthy risk for quickly developing cocaine dependence after initial cocaine use, with about one in 16 to 20 cocaine users becoming dependent within the first year of cocaine use. For marijuana and alcohol, there is a more insidious onset of the drug dependence syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In an earlier report of evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey, our research group described some interesting features about the comparative epidemiology of drug dependence. For example, as a summary population average value for the estimated millions of Americans age 15–54 years who had tried cocaine at least one time by the early 1990s, about one in six had become dependent upon cocaine (about 16–17%). Among persons who had tried marijuana at least one time, about one in 11 had become dependent upon it (about 9%). By comparison, among persons who had tried alcoholic beverages at least once, about one in 6 or 7, or 15%, had become alcohol dependent (Anthony et al. 1994). In the present study, we extend this look at the comparative epidemiology of drug dependence, but here our focus is upon estimation of the age-specific and time-specific risks of progression from first drug use to dependence, separately for marijuana, cocaine, and (for comparison) alcoholic beverages (hereinafter, ‘alcohol’).

Prior studies have conveyed estimates of age-specific risk for first alcohol use and alcohol dependence, as well as risk estimates for initiation of illicit use and dependence on controlled drugs in general (e.g., Kandel and Logan 1984; Eaton et al. 1989; Warner et al. 1995; Chen and Kandel 1995; Johnson and Gerstein 1998; Perkonigg et al. 1999; DeWit et al. 2000). The role of early onset of drug use and progression to initial and problematic use of other drugs also has been studied in some detail (e.g., Kandel 1985; Anthony and Petronis 1995; Grant 1998; Grant and Dawson 1998). However, what is especially novel about the present study is its new look at both the cumulative and instantaneous risk of drug dependence in relation to time elapsed since first use of marijuana and cocaine, with alcohol for comparison.

Whereas epidemiological studies of this type generally are regarded as valid sources of evidence, it is possible that some critics might call into question the validity or reliability of drug dependence assessments obtained in large-sample survey research as compared with what can be obtained via intensive clinical study of smaller samples (e.g., see Anthony et al. 1985; Brugha et al. 1999). Nonetheless, at least with respect to the drug dependence syndromes, recent empirical research provides evidence that epidemiologic studies can and do provide generally valid and reliable estimates of the occurrence of these conditions, as well as their corresponding ages of onset (e.g., see Prusoff et al. 1988; Langenbucher et al. 1994; Shillington et al. 1995; Wittchen et al. 1989; 1998, 1999, Shillington and Clapp 2000). In addition, the types of survival analysis we have performed with respect to drug dependence in the present study have many analogs in studies that other research teams have completed with respect to psychiatric disturbances outside the realm of drug dependence (Breslau and Klein 1999; Prescott and Kendler 1999; Horwath and Weissman 2000; Kessler et al. 2001).

In this paper, we study the risk of transition from first drug use to drug dependence using two measures of risk: the “cumulative probability” and the “instantaneous” hazard or time-specific risk of an event. Described briefly, the cumulative probability for an event is the proportion of individuals in a population who experience the event up to or through a specified time point or interval (e.g., the accumulated probability of having initiated marijuana use by age 17). In contrast, the instantaneous hazard or risk refers to the probability of event occurrence within a particular interval of time, given no prior event occurrence (Willet and Singer 1993). In the latter, the risk of becoming dependent on cocaine at age 25 is the proportion of respondents who become dependent while age 25, among those who had not become cocaine dependent up to that age. As defined, these estimates summarize the experience of all persons in the study population.

So that the results of this study might be compared with similar epidemiological evidence about other mental and behavioral disturbances (e.g., major depression), we have depicted the risk of developing drug dependence in two ways. First, we estimate the risk of dependence on marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol for all persons in the study population, without regard to their use of each drug. The resulting curves are directly comparable to those that depict the developmental periods of risk for major depression or other psychiatric disturbances (e.g., as offered by Eaton et al. 1989). Second, we restrict the analyses to individuals who have used each drug on at least one occasion, and we re-estimate the risk of becoming drug dependent for every year after first drug use. These results are more akin to post-exposure induction or latency periods of risk, once a discrete exposure has occurred. DeWit and colleagues (2000) have presented similar evidence on alcohol, based upon a survey in Canada, but made no attempt to compare the experience of alcohol consumers with the experience of marijuana and cocaine users.

Evidence about the post-exposure periods of risk is crucial whenever we seek to understand the epidemiology of conditions for which a discrete exposure is required, whether the exposure involves an infection, a toxin or a drug, irradiation, or a traumatic life event. For this reason, in this paper we also show estimates on the developmental periods of risk for first exposure, measured as the age at which individuals start to use marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol.

METHODS

The data for this study were gathered for the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). Detailed descriptions of the NCS and its procedures for assessing drug dependence are provided elsewhere (Anthony et al. 1994; Kessler et al. 1994; Warner et al. 1995). In brief, the study sample is a stratified multistage area probability sample of community residents age 15 to 54 years in the nonistitutionalized civilian population of the 48 coterminous United States, and a supplemental sample representative of students living in campus group housing. Carefully trained interviewers collected the data under close monitoring. The NCS achieved an 82.4% response rate, with 8,098 participants. This paper, and the NCS, fully comply with the Declaration of Helsinki and with research ethics regulations adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health.

Data on illicit drug use and alcohol were obtained via standardized questions adapted from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), a structured diagnostic instrument administered by trained interviewers (Robins et al. 1988; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1993). Respondents were asked the age at which they used each drug for the first time. In addition, for each drug, respondents were asked whether they had a particular problem or group of problems, and the age when problems started. Regrettably, for tobacco use, the questions asked for the age at which the respondent started to use tobacco daily for a month. For this reason, it is not possible to study transitions from first tobacco use to dependence in any detail. For many tobacco smokers, daily smoking is a manifestation of tobacco dependence. In addition, there were neither detailed questions about routes of administration nor about separate dosage forms (powder cocaine HCl, crack, hash oil); hence, this study's estimates are averaged summary values across all dosage forms and routes of administration.

Drug use initiation was made operational in relation to each respondent's answers to the standardized survey question about the age at first use of each drug. Drug dependence was assessed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition, DSM-III-R diagnosis criteria (American Psychiatric Association 1987), as made operational in the University of Michigan version of the CIDI (UM-CIDI) described by Kessler et al. (1994). In order to qualify for drug dependence, the respondent had to report at least three separate manifestations of dependence. The UM-CIDI assesses a range of clinical features characteristic of drug withdrawal syndromes, as well as behavioral manifestations of dependence such as unsuccessful attempts to stop or cut down drug use, continued use of drugs despite recognition of related physical, psychological and social problems, and role performance impairment. Final diagnoses for this study were derived via the CIDI algorithm and associated diagnostic computer programs, as were used in the original NCS reports on drug dependence (World Health Organization 1990; Cottler et al. 1991; Anthony et al. 1994).

Appropriate statistical survey methods were used to account for the complex survey design, such as clustering of respondents by sampling strata and unequal probability of selection into the NCS sample. Survival analysis methods were used to estimate the cumulative probability of first marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol use. We then estimated the risk for onset of use for each drug, that is, the risk of first marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol use during a specified year, given no history of using that drug up to that time interval. In these analyses, age is expressed in terms of years since birth.

All survival analyses were performed using the STATA software (Stata Corp. 1999), and included Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative probability of progression from first use to dependence on each drug. For these analyses, we applied two developmental perspectives: (1) time was measured chronologically in years since birth; (2) thereafter, the time scale was set as years since first use of each drug. To enhance the graphical display of the estimated risk, we used non-parametric smoothing techniques such as a median kernel smoother with cubic splines.

Interpretation of evidence from survival analysis requires answers to the following questions: (1) What is the origin for the X axis? (2) What is the time scale along the X axis? (3) What is the outcome event under investigation? (4) What is the survival analysis estimate depicted on the Y axis? and (5) Are there any noteworthy restrictions? In this study: (1) The origin first is specified as the birth year; next, it is specified as age at first use of each drug. (2) The time scale is years of life. (3) The outcome of interest is first occurrence of the dependence syndrome (i.e., age at which the full set of criteria for dependence first were met). (4) The survival analysis estimates are (a) cumulative probability, and (b) age- or time-specific risk of dependence upon each drug. (5) In the analyses of risk among users, the non-users have been excluded; otherwise, there are neither restrictions nor exclusions from the NCS sample.

Traditional test statistics such as the χ2 or t-test could not be used to test for drug-related differences in the risk of developing dependence due to the lack of independence across responses (i.e., dependence on one drug being correlated with dependence on another drug). To address this issue, multivariate response profile analyses were implemented via Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE); the GEE robust p-values are based on methods that take into account the multiple intercorrelated responses (Liang and Zeger 1986; Andrade et al. 1994; Diggle et al. 1995).

RESULTS

Figure 1 depicts the estimated age-specific risk for first use of marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol as a function of years since birth, with the estimates based upon data from 3,940 marijuana users, 1,337 cocaine users, and 7,485 alcohol users in the total NCS sample of 8,098 respondents. The peak risk for initiation of drug use was estimated to occur at age 18 years for marijuana and alcohol, with peak risk for cocaine two years later (Figure 1). When studied in comparison with values for marijuana and cocaine, the estimated risk for initiating alcohol use is seen to have higher values, with earlier occurrence, and is spread over a longer age span. An additional feature of the data is the very small risk value for ages beyond 25 years: it has been very uncommon for Americans to start the use of these drugs in the later years of life, as noted elsewhere (Anthony and Helzer 1995; Chen and Kandel 1995). The developmental period of risk for starting to use marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol is effectively completed by age 35–50 years.

Figure 2 shifts emphasis from initial drug use to the onset of drug dependence, and depicts the estimated risk for developing dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, reflecting the experience of all persons in the population so that developmental periods of risk for drug dependence might be compared with separately published periods of risk for developing major depression and other psychiatric disturbances. Here, the denominator of ‘at risk’ experience is defined in relation to all people, without respect to their history of drug-taking, and the numerator included 354 cases of marijuana dependence, 220 cases of cocaine dependence, and 1,212 cases of alcohol dependence in the total sample of 8,098 respondents. The highest risk value is observed for dependence on alcohol at about age 20–21 years; the peak risk value for marijuana dependence appears slightly earlier, at about 17 years. The estimated peak risk value for cocaine dependence occurred some seven years later, at about age 24–26 years. For marijuana dependence, the developmental period of risk has virtually ended by age 30 years; very few cases arise after this age. Not so with respect to cocaine dependence, for which the period of risk extends to just past age 35 years. However, new cases of alcohol dependence are observed to arise through the middle years of adult life, as observed elsewhere (e.g., see Eaton et al. 1989).

Age-specific risk for meeting DSM-III-R criteria of dependence, by drug, based upon all persons without differetiation of drug users and non-users. Data from the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey, 1990–92. Risk is estimated here in terms of the one-year interval that separates one age stratum from the next age stratum.

Table 1 shifts focus to the experience of drug users, and shows the estimated cumulative probability of meeting criteria for dependence, among users of marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, for specified age intervals. For those who used marijuana at least once, the estimated cumulative probability of becoming dependent on marijuana by age 54 was 10% (95% CI, 9.0–11.1%). Most cases of dependence on marijuana occurred when users were age 15–25 years old. In fact, the cumulative probability of developing dependence on marijuana remained below 1% to age 14 years among users, but increased sharply in the following 15 years and climbed to 9% by age 30 years. On the other hand, among persons who had used cocaine, the cumulative probability of cocaine dependence by age 45 years was estimated to be 21% (95% CI, 18.4–24.5%). The greatest increases in the estimated cumulative probability of cocaine dependence are seen to occur between ages 15 to 30, growing from roughly 1% to 18% during this period, thereafter with modest growth at lower rates. Starting from age 20 onward, the cumulative probability estimates for dependence on cocaine exceeded values observed for dependence on marijuana during the same developmental interval. With respect to people who had used alcohol at least once, the estimated cumulative probability of alcohol dependence by age of 55 years was about 20% (95% CI, 18.6–21.1%). Most cases met criteria for dependence on alcohol between ages 15 and 35 years.

Like Figure 2, Figure 3 presents a graphical display of the developmental periods of risk for becoming dependent upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, but it differs from Figure 2 in an important respect: Figure 3 conveys the experience of drug users only. When each study base is restricted to persons who have used each drug, the risk for cocaine dependence peaks at age 23–25 years, somewhat later than estimated peaks for alcohol and marijuana dependence, which take place during the teen years.

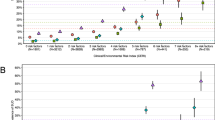

Figure 4 and its inset figure depict the estimated risk of developing dependence, with a restriction to users of each drug, and with a time scale that is set as years elapsed since first drug use. The X-axes for the larger figure and for the inset figure express number of years since first use, but each Y axis depicts a different aspect of the epidemiology of drug dependence. The Y axis in the larger figure depicts the estimated drug-specific cumulative probability of meeting dependence criteria among individuals who had used each drug, by elapsed time since first drug use. In contrast, the inset figure depicts the estimated instantaneous or time-specific risk of meeting dependence criteria for the first time. Whereas values in the larger figure grow to show how the estimated probability of becoming dependent accumulates over time since the start of each drug user's career of use, the inset figure shows the risk of becoming dependent during each year since first use among those who remained non-dependent to that year. While the X-axes in both figures depict time elapsed since first use, this does not mean that the use of the drug has followed a specific pattern. As mentioned in the methods section, no information is available to assess variation in the dosages used over time and their relation to the risk of becoming dependent on each drug. For example, it is possible that a respondent had a first cocaine use and continued using cocaine for one year without becoming dependent, stopped using cocaine for three years, and then resumed cocaine use in a more intense fashion that led him or her to meet full criteria of dependence. The NCS data and the following analyses do not allow disclosure of such differences in patterns of drug involvement.

As reflected in both the larger figure and the inset, there is continuing risk for experiencing cocaine dependence a decade or more after initial cocaine use. Both the larger figure and the inset show less explosive development of marijuana dependence among marijuana users. Whereas some 15–16% of cocaine users had developed cocaine dependence within 10 years of first cocaine use, the corresponding values are about 8% for marijuana users, and 12–13% for alcohol users (Figure 4).

Figure 4's inset clarifies that the emergence of marijuana and alcohol dependence is at roughly similar magnitudes for the first few years after initial use of these drugs. Thereafter, cases of alcohol dependence continue to accumulate, but the risk of developing marijuana dependence drops off, perhaps because illicit drug use tends to be a more transient experience than alcohol use. Some 10 years after first marijuana use, the instantaneous risk of becoming marijuana dependent has reached values near zero and there is no more accumulation of new cases. The estimated instantaneous risk of meeting criteria for alcohol dependence is about one percent per year; new cases continue to mount (Figure 4, inset).

The inset figure within Figure 4 shows that cocaine dependence emerges quite early and explosively in the initial years after first cocaine use; most of the observed cases of cocaine dependence met criteria for dependence within 1–3 years after initial cocaine use. An estimated 5.5% of cocaine users developed cocaine dependence within the first year of use; a corresponding estimate of 2.5–3.0% was observed for the period from 1–3 years after initial cocaine use. Thereafter, the estimated instantaneous risk of cocaine dependence drops to about 1.5%, and subsequently to values between one-half and one percent, or lower. Some years after first cocaine use, the estimated instantaneous risk of cocaine dependence generally is intermediate between the values reported for marijuana and alcohol.

During the initial year of use of marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, cocaine users were found to be about two times more likely to develop cocaine dependence, compared with the risk of alcohol dependence among alcohol users (odds ratio, OR, = 1.90; 95% CI, 1.12–2.22; GEE robust p = .018). In contrast, during the first year of marijuana use, the risk of meeting criteria for marijuana dependence was not found to differ from the risk of alcohol dependence (OR = 1.04, 95% CI, 0.60–0.81; GEE robust p = .88).

DISCUSSION

This report offers novel evidence about age- and time-related developmental periods of risk for first drug use and first drug dependence in the United States. It is of interest that the risk for cocaine dependence among cocaine users develops more explosively than the risk of dependence among marijuana or alcohol users, as confirmed in GEE multivariate response profile analyses that took into account the statistical interdependencies of our three response variables. The risk of becoming alcohol dependent persists for decades after first alcohol use, whereas there appears to be a shorter developmental period of risk for marijuana use and perhaps also for cocaine use.

In order to appreciate this study's new empirical evidence on the comparative epidemiology of cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol, or to discuss the findings in detail, readers may wish to know more about the study's limitations. Population estimates of this type necessarily require the use of survey research methods, with attendant difficulties such as restriction of range to household residents and the exclusion of homeless and incarcerated individuals. Nevertheless, as illustrated in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area studies, overall population estimates for drug dependence do not tend to change substantially when the experiences of non-household residents are taken into account, except perhaps when there is a specific focus on inner city populations. This is because the size of the U.S. household population is much larger than the size of the non-household population, and a large fraction of the population lives outside of the inner city (e.g., see Anthony and Helzer 1991).

Another limitation involves the assessment of clinical syndromes of drug dependence and determination of the ages at first drug use and first drug problems; there is no bioassay for these syndromes nor for first drug use. These circumstances necessitate reliance upon self-reported information. As such, these assessments are subject to all of the potential errors and biases of recall and reporting that have been described in detail elsewhere (e.g., see Anthony et al. 1985; 2000). Of particular concern is that events studied might have taken place some years before the NCS interviews were conducted. In this context, accurate recall sometimes represents a challenging cognitive task for both the young and older adults. Nonetheless, during the years of young and middle adulthood, it appears that age at first use of illicit drugs is reported with reasonably high coefficients of agreement (Prusoff et al. 1988; Wittchen et al. 1989; Labouvie et al. 1997; Shillington and Clapp 2000). The NCS used a variety of measures to reduce bias and to promote the respondent's commitment to telling the truth, but the cost of portable computer-assisted self-interviewing and programming was deemed prohibitive at that time. Hence, we acknowledge a potential limitation that can be overcome in future surveys, which might show greater (or earlier) risks for starting to use drugs and for becoming drug dependent, to the extent that computer-assisted self-interviewing promotes more complete and accurate reporting of illicit and sensitive matters (e.g., see Lessler and O'Reilly 1997; Turner et al. 1998).

Another set of inter-related limitations involves the question of reliability and validity of the National Comorbidity Survey diagnoses, already mentioned in our introduction to this paper. This set of limitations has been discussed quite thoroughly in past NCS papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry and elsewhere (e.g., see Kessler et al. 1994, 1997; Anthony et al. 1994; Warner et al. 1995; Kessler and Mroczek 1996; Wittchen 1996; Hasin et al. 1997; Pull et al. 1997; Lachner et al. 1998; Wittchen et al. 1999;). Here, we would like to add a note of clarification: large-sample epidemiological studies do not provide the same context for studies of reliability and validity as one can create in a smaller sample study where there might be multiple opportunities for repeated assessment and increasingly detailed diagnostic cross-examination. For large-sample epidemiological research, the research team generally must knock on doors of randomly selected households, and then follow disclosure and informed consent procedures required to recruit a randomly selected household member for the 1–2 h diagnostic assessment. Even when the sampled community residents are willing to complete an initial 1–2 h diagnostic assessment, many of them are not willing to repeat the assessment for the purposes of a reliability or validity study. Furthermore, the participants willing to share more of their time and effort for repeat assessments generally may not be regarded as a random or representative sample of all participants, and there is considerable uncertainty about whether resulting reliability and validity estimates actually hold for the population under study (e.g., see Anthony et al. 1985; Wittchen et al. 1999). For this reason, there are no definitive estimates of reliability or validity of the NCS drug dependence diagnoses that are based on thorough standardized clinical direct examination and re-appraisal of a proper random sample of the NCS participants. It is necessary to turn to reliability and validity estimates from separately conducted methodological studies in order to see that our standardized drug dependence diagnoses in survey research generally have substantially better reliability and validity than the corresponding survey research diagnoses for other DSM Axis I disorder categories (e.g., see Anthony et al. 1985; Janca et al. 1992; Shillington et al. 1995).

Some readers might not be aware of ‘sample space’ constraints upon the evidence; we must confess that these observed values characterize experiences in the U.S. household population during the last several decades of the 20th century, and might have no generalizability to other people, other places, or other times. For instance, the sampling scheme for the NCS did not include members of the population 55 years or over; therefore, our analyses are not informative about the risk of dependence on alcohol or other drugs for older segments of the population. Based upon prospective evidence from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area research and other studies, the risk of developing dependence on alcohol and other substances for the first time after age 55 is quite low (e.g., Eaton et al. 1989), and the risk of starting to use marijuana or cocaine after age 55 is vanishingly small (e.g., Anthony and Helzer 1995). Hence, it is most likely that our study estimates would not be altered to any great extent if older respondents had been included within the NCS epidemiological sampling frame.

The rate of transition from non-use to use and the rate of transition from use to dependence are not fixed pharmacological properties of cocaine, marijuana, or alcohol, and relatively little is known about ‘laws of epidemiology’ that govern matters such as these. Unless experimental laboratory studies have been misleading, the transition rates experienced by community-dwelling drug users are likely to have multiple determinants such as ‘host’ characteristics, as well as local variation in availability of each drug, prevailing routes of administration, dosage forms, and daily doses. For example, past and recent studies show that early onset of drug use is a predictor of subsequent development of drug-related problems (Anthony and Petronis 1995; Grant 1998; Grant and Dawson 1998; Hanna and Grant 1999), and evidence from DeWit et al. (2000) links earlier onset of alcohol use to greater cumulative risk of developing alcohol dependence, while Obot et al. (2001) have found that children of alcohol dependent parents are more likely to be early onset users of alcohol and other drugs. In addition, recent epidemiological evidence converges with clinical and laboratory evidence in support of the idea that general repertoires of behavior might displace or prevent drug use (Johanson et al. 1996). If so, the above-mentioned circumstances of environment and behavior are among the conditions and processes that govern the transition rates. Elsewhere, we have speculated and offered epidemiological evidence that features of the neighborhood and work environment impinge on risk of alcohol and drug use and dependence, in addition to vulnerabilities linked with psychiatric and behavioral disturbances such as mood disorders and antisocial personality disorder, with social status, and with male sex (e.g., see Crum et al. 1995, 1996; Muntaner et al. 1995; Petronis and Anthony 2000; Ritter and Anthony 1991; Anthony 1991; Crum et al. 1998; Anthony et al. 1994;). Recent evidence from genetic epidemiology confirms the role of inherited predispositions toward drug-taking and toward drug dependence, once drug use begins, apparently more so for men than for women (e.g., see Pickens et al. 1991; Lyons et al. 1997; True et al. 1999; Tsuang et al. 1999; Kendler et al. 2000; Xian et al. 2000).

The estimates of this study, and from prior population studies of this type (e.g., Kandel and Logan 1984; Eaton et al. 1989; DeWit et al. 1997; 2000), represent population averages over the experiences of all individuals in the study populations, including the higher and lower risk subgroups delineated in the aforementioned studies. As such, these estimates have some utility in clinical practice and in research, akin to the utility of other averaged values. These are ‘population norms’ that clinicians may use on a daily basis to guide decision-making about the care and management of individual patients, that public health workers can use to make decisions about appropriate timing of prevention activities, and that scientists may apply in planning for their future studies.

In future research, it should be possible to examine these subgroup variations and markers of individual vulnerability in more detail. In the past, most attention in etiologic research on drug dependence has been fixed upon risks of first drug use or first appearance of drug dependence. The perspective advanced in this paper is one that encourages greater attention to the timing of the transitions from first drug use to development of drug dependence.

One clear application of this shift in perspective involves genetically oriented twin studies. For the most part, twin studies of drug dependence have sorted the twin pairs into two groups: pairs that are discordant for occurrence of drug dependence (one twin ‘positive’ and one twin ‘negative’) versus pairs that are concordant (both twins ‘positive’ or both twins ‘negative’). Instead, twin studies can re-define concordance with respect to the time elapsed from first drug use to first drug dependence (or first drug problem). Twins with exactly the same elapsed time from first drug use to first dependence are concordant; otherwise, they are discordant. One advantage of this analytical approach to defining concordance and discordance is to increase the number of ‘discordant’ twin pairs, with increasing precision of study estimates and statistical power to detect environmental influences upon vulnerability to drug dependence. Determinants of lag time from first use to each drug to first dependence may become an issue in twin studies and other research on etiology of drug dependence, just as ‘rapid’ or slower transition from drug exposure opportunities to actual first use has become an issue for research on the causes of initial drug involvement (e.g., see Van Etten and Anthony 1999; Wagner and Anthony 2001).

In conclusion, estimates from this national survey represent novel evidence concerning the drug-taking experiences of the U.S. population. Analyses of time elapsed from first drug use to first drug dependence shed new light on these experiences. Directions for future research include more careful study of sub-group variation in the average values reported in this paper, such as clarification of the mechanisms by which earlier onset of drug use is associated with later increased risk of drug dependence problems.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1987): Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

Andrade L, Eaton WW, Chilcoat H . (1994): Lifetime comorbidity of panic attacks and major depression in a population-based study. Symptom profiles. British Journal of Psychiatry 165: 363–369

Anthony JC . (1991): The epidemiology of drug addiction. In Miller NS (ed), Comprehensive Handbook of Drug and Alcohol Addiction. New York, Marcel Dekker, pp 55–86

Anthony JC, Helzer JE . (1991): Syndromes of drug use and drug dependence. In Robins LN, Regier DA (eds), Psychiatric Disorders in America. New York, The Free Press, pp 116–154

Anthony JC, Folstein M, Romanoski AJ, Von Korff MR, Nestadt GR, et al. (1985): Comparison of the lay Diagnostic Interview Schedule and a standardized psychiatric diagnosis. Experience in eastern Baltimore. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42: 667–675

Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC . (1994): Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 2: 244–268

Anthony JC, Helzer JE . (1995): Epidemiology of drug dependence. In Tsuang M, Tohen M, Zahner G (eds), Psychiatric Epidemiology. New York, Wiley, pp 361–406

Anthony JC, Petronis KR . (1995): Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug Alcohol Depend 40: 9–15

Anthony JC, Neumark YD, Van Etten ML . (2000): Do I do what I say? A perspective on self-report methods in drug dependence epidemiology. In: Stone A, Turkan JS, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman HS (eds.) The Science of Self-report: Implications for Research and Practice. New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Breslau N, Klein DF . (1999): Smoking and panic attacks: an epidemiologic investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 1141–1147

Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R . (1999): A difference that matters: comparisons of structured and semi-structured psychiatric diagnostic interviews in the general population. Psychol Med 29: 1013–1020

Chen K, Kandel DB . (1995): The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. Am J Pub Health 85: 41–47

Cottler LB, Robins LN, Grant BF, Blaine J, Towle LH, Wittchen HU, Sartorius N . (1991): The CIDI-core substance abuse and dependence questions: Cross cultural and nosological issues. Br J Psychiatry 159: 653–658

Crum RM, Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Anthony JC . (1995): Occupational stress and the risk of alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 19: 647–655

Crum RM, Lillie-Blanton M, Anthony JC . (1996): Neighborhood environment and opportunity to use cocaine and other drugs in late childhood and early adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend 43: 155–161

Crum RM, Ensminger ME, Ro MJ, McCord J . (1998): The association of educational achievement and school dropout with risk of alcoholism: a twenty-five-year prospective study of inner-city children. J Stud Alcohol 59: 318–326

DeWit DJ, Offord DR, Wong M . (1997): Patterns of onset and cessation of drug use over the early part of the life course. Health Education and Behavior 24: 746–758

DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC . (2000): Age of first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry 157: 745–750

Diggle PJ, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL . (1995): Analysis of longitudinal data. New York, Oxford University Press

Eaton WW, Kramer M, Anthony JC, Dryman A, Shapiro S, Locke BZ . (1989): The incidence of specific DIS/DSM-III mental disorders: Data from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Acta Psychiatr Scand 79: 163–178

Grant BF . (1998): Age at smoking onset and its association with alcohol consumption and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse 10: 59–73

Grant BF, Dawson DA . (1998): Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse 10: 163–173

Hanna EZ, Grant BF . (1999): Parallels to early onset alcohol use in the relationship of early onset smoking with drug use and DSM-IV drug and depressive disorders: Findings form the National Longitudinal Epidemiologic Survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23: 513–522

Hasin D, Grant BF, Cottler L, Blaine J, Towle L, Ustun B, Sartorius N . (1997): Nosological comparisons of alcohol and drug diagnoses: a multisite, multi-instrument international study. Drug Alcohol Depend 47: 217–226

Horwath E, Weissman MM . (2000): The epidemiology and cross-national presentation of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 23: 493–507

Janca A, Robins LN, Cottler LB, Early TS . (1992): Clinical observation of assessment using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). An analysis of the CIDI Field Trial at the St Louis site. Br J Psychiatry 160: 815–818

Johanson CE, Duffy FF, Anthony JC . (1996): Associations between drug use and behavioral repertoire in urban youths. Addiction 91: 523–534

Johnson R, Gerstein DR . (1998): Initiation of use of alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, cocaine, and other substances in US birth cohorts since 1919. Am J Pub Health 88: 27–33

Kandel DB, Logan JA . (1984): Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood. I. Periods of risk for initiation, stabilization and decline in use. Am J Pub Health 74: 660–666

Kandel DB . (1985): Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science 190: 912–914

Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Neale MC, Prescott CA . (2000): Illicit psychoactive substance use, heavy use, abuse, and dependence in a US population-based sample of male twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57: 261–269

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS . (1994): Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51: 8–19

Kessler RC, Mroczek DK . (1996): Some methodological issues in the development of quality of life measures for the evaluation of medical interventions. J Eval Clin Pract 2: 181–191

Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC . (1997): Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54: 313–321

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Ries Merikangas K . (2001): Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biol Psychiatry 49: 1002–1014

Labouvie E, Bates ME, Pandina RJ . (1997): Age of first use: its reliability and predictive utility. J Stud Alcohol 58: 638–643

Lachner G, Wittchen HU, Perkonigg A, Holly A, Schuster P, Wunderlich U, Turk D, Garczynski E, Pfister H . (1998): Structure, content and reliability of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) substance use sections. Eur Addict Res 4: 28–41

Langenbucher J, Morgenstern J, Labouvie E, Nathan PE . (1994): Lifetime DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and opiate dependence: six-month reliability in a multi-site clinical sample. Addiction 89: 1115–1127

Lessler JT, O'Reilly JM . (1997): Mode of interview and reporting of sensitive issues: design and implementation of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing. NIDA Res Monogr 67: 366–382

Liang K-Y, Zeger SL . (1986): Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73: 13–22

Lyons MJ, Toomey R, Meyer JM, Green AI, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True WR, Tsuang MT . (1997): How do genes influence marijuana use? The role of subjective effects. Addiction 92: 409–417

Muntaner C, Anthony JC, Crum RM, Eaton WW . (1995): Psychosocial dimensions of work and the risk of drug dependence among adults. Am J Epidemiol 142: 183–190

Obot IS, Wagner FA, Anthony JC . (2001): Early onset and recent drug use among children of parents with alcohol problems: Data from a national epidemiologic survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. (in press).

Perkonigg A, Lieb R, Hofler M, Schuster P, Sonntag H, Wittchen H-U . (1999): Patterns of cannabis use, abuse and dependence over time: incidence, progression and stability in a sample of 1228 adolescents. Addiction 94: 1663–1678

Petronis KR, Anthony JC . (2000): Perceived risk of cocaine use and experience with cocaine: Do they cluster within US neighborhoods and cities? Drug Alcohol Depend 57: 183–192

Pickens RW, Svikis DS, McGue M, Lykken DT, Heston LL, Clayton PJ . (1991): Heterogeneity in the inheritance of alcoholism. A study of male and female twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48: 19–28

Prescott CA, Kendler KS . (1999): Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: a noncausal association. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23: 101–107

Prusoff BA, Merikangas KR, Weissman MM . (1988): Lifetime prevalence and age of onset of psychiatric disorders: recall 4 years later. J Psychiatr Res 22: 107–117

Pull CB, Saunders JB, Mavreas V, Cottler LB, Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blaine J, Mager D, Ustun BT . (1997): Concordance between ICD-10 alcohol and drug use disorder criteria and diagnoses as measured by the AUDADIS-ADR, CIDI and SCAN: results of a cross-national study. Drug Alcohol Depend 47: 207–216

Ritter C, Anthony JC . (1991): Factors influencing initiation of cocaine use among adults: findings from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. NIDA Res Monogr 110: 189–210

Robins LN, Wing J, Wittchen H-U, Helzer JE . (1988): The Composite International Diagnostic Interview: An epidemiologic instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Arch Gen Psychiatry 45: 1069–1077

Shillington AM, Cottler LB, Mager DE, Compton WM . 3rd (1995): Self-report stability for substance use over 10 years: data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Study. Drug Alcohol Depend 40: 103–109

Shillington AM, Clapp JD . (2000): Self-report stability of adolescent substance use: Are there differences for gender, ethnicity and age? Drug Alcohol Depend 60: 19–27

StataCorp. (1999): Stata Statistical Software. Release 6.0. Reference Manual. Stata Press, Texas

True WR, Heath AC, Scherrer JF, Xian H, Lin N, Eisen SA, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Tsuang MT . (1999): Interrelationship of genetic and environmental influences on conduct disorder and alcohol and marijuana dependence symptoms. Am J Med Genet 88: 391–397

Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Harley RM, Xian H, Eisen S, Goldberg J, True WR, Faraone SV . (1999): Genetic and environmental influences on transitions in drug use. Behav Genet 29: 473–479

Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL . (1998): Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science 280: 867–873

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1993): National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings 1991. DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 93–1980 (Hyattsville, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration).

Van Etten ML, Anthony JC . (1999): Comparative epidemiology of initial drug opportunities and transitions to first use: marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogens and heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend 54: 117–125

Wagner FA, Anthony JC . (2001): Into the world of illicit drug use: Exposure opportunity and other mechanisms linking tobacco, marijuana and cocaine use. (Submitted)

Warner LA, Kessler RC, Hughes M, Anthony JC, Nelson CB . (1995): Prevalence and correlates of drug use and dependence in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52: 219–229

Willet JB, Singer JD . (1993): Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: Why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61: 952–965

Wittchen HU . (1996): Critical issues in the evaluation of comorbidity of psychiatric disorders. Br J Psychiatry 30(Suppl):9–16

Wittchen HU, Burke JD, Semler G, Pfister H, Von Cranach M, Zaudig M . (1989): Recall and dating of psychiatric symptoms. Test-retest reliability of time-related symptom questions in a standardized psychiatric interview. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46: 437–443

Wittchen HU, Lachner G, Wunderlich U, Pfister H . (1998): Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33: 568–578

Wittchen HU, Ustun TB, Kessler RC . (1999): Diagnosing mental disorders in the community. A difference that matters? Psychol Med 29: 1021–1027

World Health Organization. (1990): Composite International Diagnostic Interview Computer Programs. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Xian H, Chantarujikapong SI, Scherrer JF, Eisen SA, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Tsuang M, True WR . (2000): Genetic and environmental influences on posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol and drug dependence in twin pairs. Drug Alcohol Depend 61: 95–102

Acknowledgements

The NCS is a collaborative epidemiologic investigation of the prevalence, causes, and consequences of psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in the United States supported by grant RO1 MH46376 from the US Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, with supplemental grant 9035190 from the W.T. Grant foundation, New York, NY (Dr. Kessler, principal investigator). Preparation of this article was supported by R01 grant award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA 09897 and DA 09897-04S2) to Dr. Anthony, and partially by grant 000358 from the National Council on Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACYT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, F., Anthony, J. From First Drug Use to Drug Dependence: Developmental Periods of Risk for Dependence upon Marijuana, Cocaine, and Alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacol 26, 479–488 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Methylphenidate with or without fluoxetine triggers reinstatement of cocaine seeking behavior in rats

Neuropsychopharmacology (2023)

-

Impulsivity and Stressful Life Events Independently Relate to Problematic Substance Use in At-Risk Adolescents

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2023)

-

Assessing the Impact of Recreational Cannabis Legalization on Cannabis Use Disorder and Admissions to Treatment in the United States

Current Addiction Reports (2023)

-

The relationship between smartphone addiction and aggression among Lebanese adolescents: the indirect effect of cognitive function

BMC Pediatrics (2022)

-

Patients admitted to treatment for substance use disorder in Norway: a population-based case–control study of socio-demographic correlates and comparative analyses across substance use disorders

BMC Public Health (2022)