Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating condition of CNS that often results in severe functional impairments for which there are no restorative therapies. As in other CNS injuries, in addition to the effects that are related to the primary site of damage, these impairments are caused by degeneration of distal regions that are connected functionally to the primary lesion site. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) counteracts this neurodegeneration, and pharmacological modulation of type-2 cannabinoid receptor (CB2R) is a promising therapeutic target for several CNS pathologies, including SCI. This study examined the effects of CB2R modulation on the fate of axotomized rubrospinal neurons (RSNs) and functional recovery in a model of spinal cord dorsal hemisection (SCH) at the cervical level in rats. SCH induced CB2R expression, severe atrophy, and cell death in contralateral RSNs. Furthermore, SCH affected molecular changes in the apoptotic cascade in RSNs – increased cytochrome c release, apoptosome formation, and caspase-3 activity. CB2R stimulation by its selective agonist JWH-015 significantly increased the bcl-2/bax ratio, reduced cytochrome c release, delayed atrophy and degeneration, and improved spontaneous functional recovery through ERK1/2 inactivation. These findings implicate the ECS, particularly CB2R, as part of the endogenous neuroprotective response that is triggered after SCI. Thus, CB2R modulation might represent a promising therapeutic target that lacks psychotropic effects and can be used to exploit ECS-based approaches to counteract neuronal degeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating neurological disease that results in severe functional impairments for which there are no restorative therapies. In addition to the primary injury, functional impairments following SCI are attributed to degenerative events in regions that are remote but functionally connected to the primary lesion site – that is, supraspinal structures. These events include cell death and structural changes and are important predictors of outcome.1, 2 However, few studies have examined the molecular and biochemical changes in remote neurons after SCIs as targets for therapeutic interventions.

The spinal cord hemisection (SCH) model is a sensitive and reliable paradigm that has been used to evaluate forelimb motor functions and changes in remote supraspinal areas that are functionally related to the primary site of injury.3 When performed at the cervical level, an SCH in rodents axotomizes nearly the entire contralateral neuronal population of the magnocellular component of the red nucleus and mimics Brown–Séquard syndrome in humans.3, 4

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) is a ubiquitous lipid signaling system that has homeostatic functions and comprises two types of G protein-coupled receptors, CB1R and CB2R, their endogenous ligands (arachidonoyl ethanolamide or anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol), and the enzymatic machinery responsible for their synthesis and degradation.5 In the brain, the ECS acts like a neurotransmitter system that governs neuronal excitability at various synapses, regulating such processes as pain, mood, appetite, memory, and motor activity.6, 7 Unlike classical neurotransmitters, endocannabinoids are not stored in vesicles but are produced on demand in response to various stimuli.6, 7

The ECS is modulated by many neurological insults, such as cerebral ischemia,8 traumatic,9 and focal brain injury,10 and it is increasingly considered a promising therapeutic target in several CNS pathologies9, 10, 11, 12, 13 including SCI.14, 15, 16, 17

After an incomplete SCI by concussion, the rapid postlesional activation of cannabinoid receptors that occurs is considered an endogenous protective mechanism.14 Simultaneous stimulation of CB1R and CB2R early before injury impedes expansion of the lesion and white matter at the epicenter of damage – effects that are maintained for up to 28 days after injury.15 This limited damage is also accompanied by greater recovery of locomotor function.16 These neuroprotective effects are prevented by simultaneous blockade of CB1R and CB2R but not of either receptor alone. In the same SCI model, Adhikary et al.17 demonstrated that a selective CB2R agonist significantly modulated immune responses at the lesion site and improved motor and autonomic functions. The potential of endocannabinoids to limit damage at the primary site has also been highlighted in many studies.8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17 Recent reports have implicated the ECS in remote damage,10 but the function of the ECS in supraspinal structures after SCI has not been examined.

In this study, we determined the effects of CB2R modulation on the fate of the axotomized rubrospinal neurons (RSNs) and on spontaneous functional recovery after SCH at the cervical level in rats. Beginning 7 days after damage, SCH induced severe atrophy and cell loss and upregulated CB2R in axotomized RSNs. Notably, neuronal degeneration proceeded concomitantly with molecular changes in the apoptotic cascade – that is, greater cytochrome c (cyt-c) release from damaged mitochondria, cyt-c/Apaf-1 binding, and caspase-3 activity. CB2R stimulation by its selective agonist JWH-015 (JWH) significantly increased the bcl-2/bax ratio, reduced cyt-c release, delayed atrophy and degeneration, and improved spontaneous functional recovery through ERK1/2 inactivation. Thus, CB2R modulation is a therapeutic target that might counteract the remote degeneration of supraspinal regions after SCI.

Results

SCH modulates the expression of CB2R in axotomized rubrospinal neurons

We examined CB1R and CB2R expression in the red nucleus (RN) of unlesioned (CTRL) and lesioned (SCH) animals by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and western blot. In the RN of CTRL animals, CB1R and CB2R were nearly absent, based on mRNA and protein levels (Figures 1a and b). SCH did not modify CB1R expression over time (Figures 1a and b).

Spinal cord hemisection induces cannabinoid receptor (CBR) expression in contralateral red nucleus. (a and b) CB1R and CB2R mRNA and protein levels in control unlesioned animals (CTRL) and after spinal cord hemisection (SCH) at various time points after damage (7, 14, 21, and 60 days), expressed as percentage of CTRL. (c) Triple-labeled and merged confocal images of CB2R (red), Fast-blue (FB; gray), and NeuN (green) in red nucleus of control (CTRL) and 7 days after SCH. (d) Histogram of percentages of CB2R-positive, FB-positive, and CB2R/FB double-positive neurons in CTRL and SCH at various times after damage. Data are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=5/group). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus CTRL. Scale bars: 20 μm

In contrast, SCH significantly upregulated CB2R mRNA and protein at 7 days after injury (Figures 1a and b) that declined at 21 days, nearly reaching CTRL levels at 60 days after injury (Figures 1a and b). Consistent with our biochemical results, we noted strong induction of CB2R in the RN of SCH animals by immunohistochemistry.

To avoid difficulties in limiting RN borders after SCH because of axotomy-induced cell shrinkage, RSNs were retrogradely labeled by Fast-blue (FB) injection at C5/C6 on the right side of the cord (see Materials and Methods). In the RN of SCH animals, CB2R was expressed almost exclusively by FB-positive neurons, confirming the neuronal phenotype and spinal projection of these cells (Figure 1c). In CTRL animals, ∼90% of RSNs were FB positive, but did not express CB2R (Figure 1d). At 7 days after SCH, ∼75% of RSNs that were FB positive expressed CB2R, roughly 15% were FB positive and CB2R negative, and the remaining cells were FB negative and CB2R positive (Figure 1d). Notably, at subsequent time points, we observed a progressive decline in FB/CB2R positivity and a parallel rise in FB/CB2R negativity in RSNs (Figure 1d).

Mitochondrial damage accompanies RSN atrophy and degeneration

SCH induces progressive and severe shrinkage of RSN bodies.18, 19 Consistent with this finding, at 7 days after SCH, axotomized RSNs shrank, and their cross-sectional area decreased compared with CTRL (Figure 2a). By FB/Nissl staining, the reduction in area was accompanied by a progressive loss of RSNs, based on stereological RSNs cell counts. The effects of SCH on RSNs were expressed as the ratio of the number of RSNs after SCH to that of RSNs of unlesioned animals (CTRL) – that is, the experimental/unlesioned (E/C) ratio. From days 7 to 60, the E/C ratio fell from ∼70 to ∼48 (Figure 2b).

Spinal cord hemisection induces degenerative changes in axotomized red nucleus. (a) Histograms of soma sizes of magnocellular rubrospinal neurons at various time points after SCH (7, 14, 21, and 60 days), expressed as percentage of unlesioned (CTRL) area. (b) Histograms of stereological counts of FB/Nissl-stained RSNs neurons at various time points after SCH (7, 14, 21, and 60 days), expressed as experimental/unlesioned (E/C) ratio. (c) Flow cytometry histograms of NeuN-positive cells in RN at various time points after SCH (7, 14, 21, and 60 days), expressed as percentage of CTRL. (d) Flow cytometry histograms of Live/Dead-positive cells, expressed as percentage of CTRL. (e) Confocal images from red nucleus of CTRL and SCH animals at 7 days after damage stained with Fast-blue (blue) and reacted with NeuN (red) and cytochrome c antibodies (green). (f) Representative immunoblots and densitometric graphs of cytosolic levels of cytochrome c in RN of CTRL and SCH animals at various time points after damage (7, 14, 21, and 60 days). Data are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=5/group). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 versus CTRL. Scale bars: 50 μm

The response of RSNs to SCH has been debated by many groups over whether axotomy primarily induces atrophy or cell death.20, 21 We stained dissociated RSNs with NeuN and LIVE/DEAD to measure neuronal cell count and death, respectively, at various stages after SCH. By cytofluorimetric analysis, we noted a decrease in neuronal cells in SCH and greater cell death, confirming our morphological data. At 7 days after SCH, we observed significant neuronal loss (Figure 2c) and a concomitant increase in dying cells (Figure 2d). As the lesion progressed, neuronal loss reached 50% and cell death increased by ∼60% after 60 days of SCH (Figure 2d).

To characterize the cellular events that are affected by SCH, we examined the involvement of apoptosis in inducing the morphological changes in RSNs. Mitochondria are significant in the initiation of apoptosis,22 and the release of cyt-c from damaged mitochondria is a crucial pro-apoptotic factor.23

At 7 days post SCH, the majority of FB-positive RSNs had intense and diffuse cyt-c immunostaining into the cytosol that was absent in FB-positive RSNs of CTRL, indicating cyt-c release from damaged mitochondria (Figure 2e).

Consistent with the immunohistochemical data, at 7 days after the lesion, SCH significantly increased the cytosolic cyt-c fraction as observed by western blot of the mitochondrial–cytosolic protein fractionation (Supplementary Figure 1) that leveled out at subsequent time points (Figure 2f).

Next, we examined the apoptotic pathway downstream of cyt-c release. By co-immunoprecipitation, the binding between cyt-c and Apaf-1 rose significantly after SCH compared with CTRL (Figure 3a), concomitant with decreased binding between Apaf-1/hsp70 and Apaf-1/hsp90 (Figure 3b). The cyt-c/Apaf-1 interaction returned to prelesion levels at later time points, and the Apaf-1/hsp70 and Apaf-1/hsp90 associations weakened progressively (Figure 3b).

Spinal cord hemisection induces mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in rubrospinal neurons. (a) Representative immunoblotting and densitometry of Apaf-1-precipitated cyt-c expression in CTRL and SCH animals. (b) Representative immunoblotting and densitometry of Apaf-1-precipitated hsp-70 and hsp-90 expression in CTRL and SCH animals after damage (7, 14, 21, and 60 days). (c) Time course of caspase-3 activity in RN of CTRL and after SCH (7, 14, 21, and 60 days). Data are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=5/group). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison tests *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; versus CTRL

Caspase-3 activation is an irreversible step in the commitment of a cell toward apoptosis.24 Thus, we examined the apoptotic pathway downstream of apoptosome formation to determine the fate of axotomized neurons. Caspase-3 activity differed between 7 and 21 days post SCH (Figure 3c), falling to prelesion values at the last time point.

CB2R stimulation after SCH reduces atrophy and delays rubrospinal neuronal loss

To determine the function of CB2R upregulation in RSNs after SCH, we modulated CB2R pharmacologically by administering a selective CB2R agonist (JWH) or antagonist (SR144528 (SR2)) SCH (Figure 4a) and to CTRL and SCH animals (Supplementary Table 1). After 7 days of treatment, animals were killed immediately (Figure 4b) or after 14 (Figure 4c) or 53 days (Figure 4d).

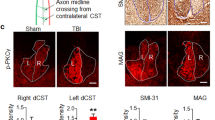

Schematic of spinal cord hemisection (SCH) model and of experimental protocols employed in the study. (a) Because of the crossed organization of the rubrospinal tracts, a right cervical hemisection axotomizes virtually all neurons of the contralateral red nucleus (RN) that were labeled by a single injection of the retrograde tracer Fast-blue (FB) performed at level C5/C6 at 10 days before spinal cord hemisection at the C3/C4 level. (b–d) After spinal cord hemisection (SCH; day 0), CTRL (unlesioned rats) and SCH rats were divided into three groups and treated with saline (SCH-sal), JWH-015 (SCH-JWH), or SR144528 (SCH-SR2) for 7 days and killed (b) immediately after treatment; (c) 14 days after treatment (day 21); and (d) 53 days after treatment (day 60)

By quantitative analysis of RSN cross-sectional area, the mean area of RSNs was 477 μm2 in all groups of unlesioned saline-treated controls (CTRL-sal). Similar results were obtained for unlesioned JWH-treated (CTRL-JWH, 481 μm2) and SR2-treated (CTRL-SR2, 484 μm2) controls. Thus, the mean area of unlesioned saline-treated control cells was used as the reference. Data from SCH groups are reported as a percentage versus the CTRL-sal area.

After SCH, cell size declined in all experimental groups. The CB2R agonist JWH had a significant protective effect on RSN cell size (Figure 5a). At all time points considered, there were significant differences in RSN cell area between SCH-sal and SCH-JWH (Figure 5a), whereas RSN area of SCH-SR2 and SCH-sal groups did not differ significantly. Nevertheless, RSNs in the SCH-SR2 group tended to decrease in size (Figure 5a).

JWH-015 delays SCH-induced rubrospinal neuron degeneration. (a) Histograms of soma sizes of magnocellular rubrospinal neurons in SCH-saline (SCH-sal), SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH), and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2) at 7, 21, and 60 days after injury (see Materials and Methods). Soma area is expressed as percentage of unlesioned (CTRL) area. (b) Histograms of stereological counts of FB/Nissl-stained rubrospinal neurons, expressed as experimental/unlesioned (E/C) ratio, in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated groups at 7, 21, and 60 days after injury (see Materials and Methods). (c) Flow cytometry histograms of NeuN-positive cells in RN of SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated groups at 7, 21, and 60 days after injury expressed as percentage of CTRL. (d) Flow cytometry histograms of Live/Dead-positive cells in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated groups at 7, 21, and 60 days after injury expressed as percentage of CTRL. (e) Representative immunoblots and densitometric graphs of time course of bcl-2/bax ratio in red nucleus of CTRL and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals at 7, 21, and 60 days after injury. Intensities of bcl-2 and bax bands are expressed as bcl-2/bax ratio. (f) Representative immunoblots and densitometric graphs of time course of cytochrome c release (cytc) in red nucleus of CTRL and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals at 7, 21, and 60 days after injury. Data are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=5/group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001

JWH also mitigated RSN cell loss (Figure 5b). Indeed, at all time points considered, there were significant differences in treatment effect on the E/C ratio between SCH-sal and SCH-JWH and between SCH-SR2 and SCH-JWH (Figure 5b), whereas E/C ratio of SCH-SR2 and SCH-sal groups did not differ significantly. Nevertheless, E/C ratio in the SCH-SR2 group tended to decrease (Figure 5b).

CB2R stimulation increases the bcl-2/bax ratio and decreases cyt-c release from damaged mitochondria

Cell death and survival following CNS injury can result from alterations in the intracellular balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic factors, of which the bcl-2/bax ratio is an important component.25 After SCH, the bcl-2/bax ratio in the RN, as expected, fell significantly, but CB2R activation by JWH influenced the SCH-induced changes in bcl-2/bax ratio. At 7 and 21 days after injury, the SCH-JWH group had significantly higher bcl-2/bax ratios compared with the SCH-sal and SCH-SR2 groups (Figure 5c). Conversely, no significant differences were observed between the SCH-sal and SCH-SR2 groups. At 60 days, the bcl-2/bax ratio was similar in all SCH groups (Figure 5c).

These data were confirmed by analysis of cyt-c release from damaged mitochondria of RSNs into the cytosol. SCH-JWH animals released less cyt-c than SCH-sal and SCH-SR2 animals at 7 and 21 days (Figure 5d). At 60 days, the level of cyt-c release was similar in all SCH-treated groups (Figure 5d).

CB2R stimulation improves spontaneous functional recovery after SCH

Following SCH, as in earlier reports, the animals had a closed forepaw on the injured side and uncoordinated overground locomotion. No deficits were observed in the forelimb on the contralateral side.

Motor performance was analyzed by beam-walking test at 0 (CTRL), 1, 3, and 5 days and by catWalk at 7, 21, and 60 days. The beam-walking data are shown in Figure 6a. At 1 day after SCH, the SCH-Sal, SCH-JWH, and SCH-SR2 groups experienced uniform, severe motor impairments (Figure 6a). From day 3, SCH-JWH animals had better beam-walking scores than the SCH-sal and SCH-SR2 groups (Figure 6a). No differences on score were observed between SCH-sal and SCH-SR2 (Figure 6a).

JWH-015 treatment improves functional recovery after SCH. (a) Long-term evaluation of scores in beam-walk test of unlesioned (CTRL) and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals. (b) Long-term evaluation of print length, expressed in mm of right forepaw in unlesioned (CTRL) and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals measured with catWalk. (c) Long-term evaluation of print width measure (mm) of right forepaw in unlesioned (CTRL) and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. (d) Long-term evaluation of print area (mm2) of right forepaw in unlesioned (CTRL) and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. (e) Long-term evaluation of Max contact area (mm2) of right forepaw in unlesioned (CTRL) and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. (f) Long-term evaluation of regularity index expressed as percentage in unlesioned (CTRL) and SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. Data are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=10/group). Two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 SCH-JWH versus SCH-sal; ##P<0.001; ###P<0.0001 SCH-JWH versus SCH-SR2

CatWalk data are reported in Figures 6b–f. All SCH groups developed clear deficits in all parameters on day 7. In subsequent days, all groups generated recovery curves that never reached control values. However, the SCH-JWH findings differed significantly from the SCH-sal or SCH-SR2 data at all time points. No differences were observed between the SCH-sal and SCH-SR2 data (Figures 6b–f).

These data demonstrate that CB2R stimulation significantly improves spontaneous functional recovery after SCH.

CB2R stimulation protects rubrospinal neurons by ERK1/2 inactivation

Having demonstrated the positive effects of JWH on cell area and survival as well as on functional recovery, we addressed the question of which signaling pathway might be responsible for CB2R-mediated neuroprotection.

In various cell death paradigms, CB2R can trigger phosphorylation cascades that involve ERK1/2 and p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3k)/Akt signaling.10, 26 Evaluation of the phosphorylation status of ERK1/2, p38, JNK, and PI3k/Akt in CTRL and SCH animals treated with saline or with a CB2R agonist or a CB2R antagonist showed that the activation of p38, JNK, and PI3k/Akt was neither affected by the lesion nor after CB2R modulation (data not shown). Conversely, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was significantly increased in SCH group compared with CTRL (Figure 7a) and CB2R stimulation caused ERK1/2 dephosphorylation, whereas CB2R inhibition caused an increase of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 7a).

CB2R mediates neuroprotection through ERK1/2 dephosphorylation. (a) Representative immunoblots and densitometric graphs of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (pERK1/2) in red nucleus of CTRL, SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-SR144528 (SCH-SR2)-treated animals at 7 days after injury. (b) Histograms of soma sizes of magnocellular rubrospinal neurons in SCH-saline (SCH-sal), SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH), and PD98059 (SCH-PD) at 7 days after injury (see Materials and Methods). Soma area is expressed as percentage of unlesioned (CTRL) area. (c) Histograms of stereological counts of FB/Nissl-stained rubrospinal neurons, expressed as experimental/unlesioned (E/C) ratio, in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated groups at 7 days after injury. (d) Representative immunoblots and densitometric graphs of time course of bcl-2/bax ratio in red nucleus of SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals at 7 days after injury. Intensities of bcl-2 and bax bands are expressed as bcl-2/bax ratio. (e) Representative immunoblots and densitometric graphs of time course of cytochrome c release (cyt-c) in red nucleus of SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals at 7 days after injury. Data are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=5/group). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001

To determine the role of ERK1/2 signaling in CB2R stimulation effects, we irreversibly inhibited ERK1/2 by intracerebroventricularly injecting PD98059 at 30 min before SCH (SCH-PD; Supplementary Table 1). PD98059 treatment, as expected, induced ERK1/2 inactivation after SCH (Supplementary Figure 2). Notably, after SCH, inactivation of ERK1/2 was associated with a significant reduction of RSN atrophy (Figure 7b), higher neuronal survival (Figure 7c), higher bcl-2/bax ratios (Figure 7d), reduction of cyt-c release (Figure 7e), and greater functional recovery (Figures 8a–f) as compared with saline-treated SCH group.

PD98059 treatment improves functional recovery after SCH. (a) Long-term evaluation of scores in beam-walk test of SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals. (b) Long-term evaluation of print length, expressed in mm of right forepaw in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals measured with catWalk. (c) Long-term evaluation of print width measure (mm) of right forepaw in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. (d) Long-term evaluation of print area (mm2) of right forepaw in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH), and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. (e) Long-term evaluation of Max contact area (mm2) of right forepaw in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. (f) Long-term evaluation of regularity index expressed as percentage in SCH-saline (SCH-sal)-, SCH-JWH-015 (SCH-JWH)-, and SCH-PD98059 (SCH-PD)-treated animals measured with the catWalk. Data are expressed as mean±S.D. (n=5/group). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison tests. #P<0.05; **P<0.001; ***P<0.0001 SCH-sal versus SCH-PD

Consistent with the neuroprotective role of CB2R-mediated ERK1/2 inactivation after SCH, no differences on RSN atrophy (Figure 7b), neuronal survival (Figure 7c), bcl-2/bax ratios (Figure 7d), cyt-c release (Figure 7e), and functional recovery (Figures 8a–f) were observed between JWH and PD treatments.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated: (1) de novo induction of CB2R in RSNs after SCH; and, under selective CB2R agonism (2) attenuation of RSN atrophy and cell loss; (3) increase in bcl-2/bax ratio in the RN; (4) decrease in cyt-c release; and (5) improvement in functional recovery; and finally (6) all CB2R neuroprotective effects are ERK1/2 dependent.

The SCH model is a sensitive and reliable paradigm for evaluating supraspinal changes after spinal damage.3, 4 Degeneration occurs in distal areas that are functionally related to the primary site of injury – a phenomenon that is termed ‘remote damage’2 that influences postlesional impairments.27

After lesions develop in their axons, the intracellular machinery of RSNs rearranges, wherein cytoskeletal proteins, regeneration-associated genes, and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) expression modulate.26, 28, 29 In contrast, less is known about changes in receptor expression patterns. Our data demonstrate that CB2R expression, although it is absent under physiological conditions, is induced by axonal damage in RSNs, peaking at 7 days post lesion, and subsequently fading. The transient CB2R peak can be interpreted taking into account that, after axotomy, different systems are active transitorily, each one in precise time windows. Within remote damage models, it is worth recalling that a similar sequential time pattern has been reported in the hemicerebellectomy (HCb) model.10

Changes in CB2R expression occur in many models. In primary lesion sites of traumatic and vascular brain injuries and in SCIs, only glial cells have been reported to experience altered CB2R expression.14, 30, 31 In distal areas, CB2R levels modulate in neurons in a cerebellar model of remote damage.10, 32 CB2R expression in neurons remains debated.33, 34, 35

In this study, CB2R was lacking from unlesioned animals, consistent with the general model of low or absent CB2R expression in the brain. Conversely, the upregulation of CB2R after development of a lesion in remote neurons, but not astrocytes or microglial cells, contrasts with what has been reported in the primary lesion site after SCI, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and vascular insults.14, 30, 31

Following SCH, RSNs enter a chronic injury state, and the relationship between atrophy and cell death has been largely debated.20, 21 Axotomized neurons progress through an orderly series of morphological changes, including shrinkage, atrophy, and eventually death,18, 19, 21 as reported in RSNs after cervical axotomy by several groups.21, 36, 37, 38 Nevertheless, whether cells die or merely become atrophic remains unknown. Axotomized RSNs evolve in a chronic atrophic state with cell death only at very late stages;20, 39 yet, studies suggest that axotomy by SCH affects a significant and progressive loss of RSNs.21, 36, 37, 38, 40 This dispute is relevant with regard to timing neuroprotective and regenerative interventions, in which the demonstration that the number of RSNs decreases after SCH is a critical issue, wherein counting method, species, and age might account for these discrepancies.

The cell loss that we observed, based on unbiased stereology methods and cytofluorimetry, supports previous reports of RSN death after SCH.21, 36, 37, 38, 40 Despite the significance of the atrophy/death dilemma, the intracellular cascades in RSNs after SCH that might address this issue have not been studied. In this report, we examined axotomy-induced neuronal death in RSNs by characterizing key elements of the apoptotic cascade: cyt-c release, apoptosome formation, and caspase-3 activation. All of these indices confirmed SCH-induced activation of the mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic cascade in RSNs. Beginning on day 7 after SCH, significant amounts of cyt-c were released into the cytosol, inducing apoptosome formation, as evidenced by Apaf-1/cyt-c binding that in turn mediated caspase-3 activation, indicating the commitment of RSNs irreversibly toward apoptotic cell death. These data indicate that at this stage cell commitment is already established, indicating, in contrast to previous reports,20, 41 the importance of the earlier events, namely before day 7 after SCH, to correctly tailor neuroprotection.

Most therapeutic approaches for SCI limit the development of secondary damage through neuroprotective measures for acute SCI.42 Nevertheless, the supraspinal centers are considered to be crucial for recovery. To this end, various strategies that target RSNs have been tested.41, 43, 44, 45

Our study has demonstrated novel neuroprotective effects of CB2R stimulation on RSNs after SCH. Selective CB2R activation by JWH reduced SCH-induced atrophy and cell loss by delaying RSN degeneration.

The treatment was administered for 7 days, and data were collected immediately and 14 and 53 days after treatment suspension. Significant neuroprotective effects were apparent immediately after cessation and maintained at all subsequent points. Nevertheless, in a comparison with untreated lesioned animals, the slope of the degeneration curve was similar in all groups, suggesting that CB2R-mediated neuroprotection delays but does not halt degeneration. After JWH treatment was withdrawn, the degenerative phenomena recommenced. The delay-effect hypothesis is confirmed by the bcl-2/bax ratio and cyt-c release data. CB2R modulation of these indices is high immediately after suspension of the treatment but declines at day 21 and disappears at day 60, consistent with reactivation of the apoptotic cascade.

CB2R-dependent anti-apoptotic effects have been seen in various in vitro46 and in vivo models of neuronal damage.10, 32, 47 Most data implicate mitochondrial protection as the most significant factor of CB2R-mediated neuroprotection,10, 32 for which PI3k/Akt signaling, bcl-2, and hsp70 are key elements that remain undefined. CB2R-mediated neuroprotection, at least in the in vivo model of HCb, requires interactions with the nitric oxide (NO) system.32 In this model, nNOS inhibition blocks its neuroprotective effects. These aspects have not been examined in SCH. Nevertheless, previous data on nNOS upregulation in RSNs after SCH26 suggest that similar CB2R/NO interactions can also occur in this model.

After brain damage, different signaling mechanisms operate to account for the variety of the retrograde responses occurring after injury,27 all requiring the involvement of sophisticated mechanisms that link signaling systems with intracellular transport machineries.

CB2R is able to signal through ERK, JNK, and p38 and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K).10, 48 In the present study we showed that CB2R-mediated neuroprotection occurred through ERK1/2 pathway, whereas the other major signaling routes were not involved. CB2R stimulation selectively changed SCH-induced ERK1/2 activation. In particular, CB2R stimulation counteracted the lesion-induced effects by reducing ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas CB2R antagonist treatment tended to highly maintain the SCH-induced ERK1/2 activation. The importance of ERK1/2 signaling in neuroprotection was further sustained by treatment with a selective ERK1/2 inhibitor (PD98059). Pretreatment with PD98059 reduced all lesion-induced effects, namely RSN atrophy and cell death (Figures 7b and c), cyt-c release (Figure 7e), and improved functional recovery (Figures 8e and f).

The present data converge in indicating ERK1/2 as the signaling route through which CB2R mediates neuroprotection in SCH. This pathway is quite different from the one demonstrated to funnel neuroprotective CB2R signal after HCb, namely PI3k/Akt.10 In spite of the different intracellular signaling, in both models, CB2R stimulation prevents axotomy-dependent mitochondrial failure. Why CB2R will execute its neuroprotective functions through PI3k/Akt or ERK1/2 pathway according to the cell type remains to be defined. Nevertheless, it is worth recalling that in other models, stimulus and, particularly, cell type have been shown to be critical in determining which signaling is triggered by cannabinoid receptor stimulation.49

The neuroprotective effects of CB2R have been observed in different brain injury models,10, 50, 51 for which various mechanisms have been proposed. In stroke the CB2R immunomodulatory effect has been considered preeminent,50, 51 whereas CB2R has anti-apoptotic effects on central neurons in a model of HCb.10 In SCI models, CB2R has immunomodulatory effects on primary lesions16, 17 and anti-apoptotic effects on areas of remote damage (present study). Thus, although the complex mechanisms that are mediated by the ECS after brain lesions cannot be defined based on current data, the significance of ECS signaling in life–death decisions is evident in many brain pathologies.

After incomplete SCI, animals spontaneously recover locomotor function,52 and in our model, untreated SCH rats recovered gait progressively. CB2R stimulation, in parallel with the delay in degeneration, improves spontaneous recovery, based on our beam-walking and catWalk data. Nevertheless, establishing a causal link between sparing neuronal death and improving functional recovery is difficult. Recovery after SCI requires rearrangements at many levels in the spinal and supraspinal circuits, and the effects of CB2R modulation might differ between centers and cell types – neuronal or glial – by time and location. Functional recovery after SCI is a complex phenomenon that is not limited to a single brain structure or intracellular signaling pathways,53 hence requiring further study aimed at unraveling the underlying interactions between different brain structures and multiple signaling pathways.

Materials and Methods

Animals and spinal cord hemisection

Adult male Wistar rats (200–250 g) were obtained from Harlan (Udine, Italy) and maintained in our animal facilities on a 12 : 12-h light/dark cycle, receiving food and water ad libitum. Animals were handled in accordance with the guidelines published in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the principles laid out in the Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience Research published by the Society for Neuroscience, and European Union guidelines (Council Directive 86/609/EEC). Protocol was approved by Italian Ministry of Health. Special care was taken to use the minimum number of animals required for statistical accuracy. For surgical procedures, the rats were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of Rompun (xylazine, 20 mg/ml, 0.5 ml/kg; Bayer, Milan, Italy) and Zoletil (tiletamine and zolazepam, 100 mg/ml, 0.5 ml/kg; Virbac, Milan, Italy).

At 10 days before lesion, animals underwent a right-side C5/C6 intraspinal injection of FB to retrogradely label the cervical projecting neurons of the RN (Figure 4a). For this purpose, hair overlying the cervical vertebrae was removed, the skin was treated with betadine and incised, and the layers of muscle were bluntly dissected. The dura was removed using blunt iridectomy scissors and fine forceps and a right-side C5/C6 intraspinal injection of 5 μl of 2% FB (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; F5756) was performed. After FB injection, the muscles were sutured in layers and the skin was closed with wound clips. After 10 days, animals underwent spinal cord injury surgery. After anesthesia (as above), the skin was treated with betadine and incised, and the layers of muscle were bluntly dissected. A dorsal unilateral laminectomy was performed at C4 to expose the dura-covered spinal cord. The dura was removed using blunt iridectomy scissors and fine forceps. Vertebral segment C4 (corresponding to spinal segment C3/4) was identified by counting of vertebral spines from segment T2. Using sharp iridectomy scissors, a lateral SCH was performed. To ensure the completeness of the injury, a 30-gauge needle was swept through the injury site. Muscle and skin layers were repaired using 5-0 vicryl sutures and rats were allowed to recover on a heated blanket before being returned to their home cage. Control (CTRL) animals received only a dorsal unilateral laminectomy at C4 to expose the dura-covered spinal cord.

After surgery, animals received an analgesic (2.5 mg per subcutaneous injection of Rimadyl; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) once per day for 5 days and antibiotics (1.25 mg/250 g body weight intraperitoneal injection of Baytril; Bayer) once per day for 3 days. Animal weights were recorded daily for a week post surgery, and twice a week thereafter. Bladder function was also assessed for 7 days post surgery, but every animal retained bladder function postoperatively and no expressions were necessary. The animals were monitored for hydration and eventual infections until the end of the experiment. SCHs were histologically verified postmortem. Incompletely injured or overhemisected rats were subsequently eliminated from our study.

Drug treatment

The following CB2R agonist and antagonist, respectively, were used: JWH (3 mg/kg, i.p./daily; Tocris, Bristol, UK) and SR2 (3 mg/kg, i.p./daily; Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Furthermore, the selective ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) was injected intracerebroventricularly (2 μl; 200 μM) 30 min before damage in SCH-sal group. Treatments in the different experimental groups are shown in detail in Supplementary Table 1.

In the present study, three different treatment protocols were employed: (1) CTRL and SCH animals were treated for 7 days with JWH, SR2, or saline and killed immediately after the end of treatment (Figure 4b); (2) CTRL and SCH animals were treated for 7 days with JWH, SR2, or saline and killed after 14 days of treatment suspension (day 21; Figure 4c); and (3) CTRL and SCH animals were treated for 7 days with JWH, SR2, or saline and killed after 53 days of treatment suspension (day 60; Figure 4d).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Rats were perfused transcardially with 250 ml of saline followed by 250 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in a phosphate buffer (PB; 0.1 M; pH 7.4) under anesthesia induced by i.p. injection of sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg). Each brain and spinal cord was removed immediately, post-fixed in the same fixative for 2 h and, after three washes in PB, transferred to 30% sucrose in PB solution at 4°C until they sank. Brains and spinal cords were cut into four series of 30 μm-thick transverse sections by means of a freezing microtome and were collected in PB.

To investigate the cellular population that expressed CB2R, sections presenting FB-positive neurons were incubated overnight with a cocktail of primary antibodies, including rabbit anti-CB2R (1 : 200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and mouse anti-NeuN (1 : 200; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). All primary antibody solutions were prepared in PB and 0.3% Triton X-100 and were incubated overnight. Each incubation step was followed by three 5-min rinses in PB. Afterwards, sections were incubated for 2 h at RT with a cocktail of secondary antibodies, including Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse (1 : 200; Invitrogen, Monza, Italy) and Alexa Fluor 543-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (1 : 200). Sections were examined under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM700, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with four laser lines: violet diode emitting at 405 nm (for DAPI), argon emitting at 488 nm, and helium/neon emitting at 543 nm and 633 using a 40 × / 0.5 NA oil objective. Images were exported in TIFF format, contrast and brightness were adjusted, and final plates were composed with Adobe Illustrator CS3 (San Jose, CA, USA) or Corel Draw 9 (Ottawa, ON, Canada).

Neuronal cross-sectional area measurement

For the measurement of neuronal cross-sectional area, Nissl staining was performed on sections presenting FB-positive neurons. As atrophy of rubrospinal neurons is recognized to make the borders of the axotomized RN less distinct,20 FB retrograde labeling was used as an anatomical reference for demarcating the magnocellular RN. Quantification of RSN cell size and cell number was performed using five alternate sections of 30-μm regularly spaced throughout the entire RN rostrocaudal extension. Only neurons identified by a clear nuclear profile were included for analysis. RSN mean cell area was expressed as percentage of RNS mean cell area of CTRL animals.

Stereological analyses

To assess the extent of cell loss in RN following SCH, stereological cell count of FB/Nissl-stained RSNs, identified by a clear nuclear profile, was performed. To better appreciate the effects of SCH on RSN cell loss, we related the number of surviving RSNs to the number of neurons present in the RN of unlesioned animals (CTRL), here indicated as E/C index.

Quantitative analyses were limited to the RN of the experimental side projecting to the lesioned spinal cord. Using the Stereo Investigator System (MicroBrightField Europe e.K., Magdeburg, Germany), an optical fractionator, stereological design was applied to obtain unbiased estimates of total Nissl-stained and FB-positive neurons. A stack of MAC 5000 controller modules (Ludl Electronic Products, Ltd, Hawthorne, NY, USA) was configured to interface an Olympus BX 50 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a motorized stage and a HV-C20 Hitachi color digital camera (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) with a Pentium II PC workstation. A three-dimensional optical dissector counting probe (x, y, z dimension of 30 × 30 × 10 μm, respectively) was applied. The RN was outlined using the 4 × objective and FB was used as an anatomical reference for demarcating the magnocellular RN, although whereas the 100 × oil immersion objective was used for marking the neuronal cells. Total number of RSNs was estimated according to the formula given below:

where SQ represents the total number of neurons counted in all optically sampled fields of the RN, ssf is the section sampling fraction, asf is the area sampling fraction, and tsf is the thickness sampling fraction.

Fluorometric assay of caspase-3 activity

After RN isolation, tissues were homogenized in lysis assay buffer containing 100 mM Hepes (Sigma, H4034), pH 7.4, 0.1% Chaps (Sigma, 3023), 1 mM EDTA (Sigma, E5134), 10 mM DTT (Sigma, D9779), and 1 mM PMSF (Sigma, 7626), and lysed by subsequent freezing in liquid N2 and thawing at 37°C three times. After centrifugation at 11 500 × g for 5 min, the protein concentration of resulting supernatant was quantified, and proteins were incubated at 37°C in lysis assay buffer containing 50 mM Ac-DEVD-AMC (BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA, USA; 556449). The fluorescence was measured at an excitation and emission wavelength of 380 and 460 nm, respectively, as previously described.54 Caspase-3 activity in the SCH animals was expressed as percent increase in absorbance relative to CTRL animals.

Mitochondrial and cytosolic fraction

RNs were homogenized in Buffer A (320 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM PMSF), with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, P8340) by 30 strokes with a glass Pyrex micro homogenizer (Sigma). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 10 000 × g for 20 min to obtain the mitochondrial pellet and the supernatant. The mitochondria-containing pellet was washed three times with Buffer B (250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EGTA, Sigma, E3889, 10 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 7.4) by centrifugation for 10 min at 10 000 × g. The supernatant was centrifuged at 100 000 × g for 1 h to generate the cytosolic fraction.

Western blotting

RNs were homogenized in lysis buffer (320 mM, sucrose, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mM PMSF) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, P8340), incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 13 000 × g for 20 min. The total protein content of resulting supernatant was determined. Proteins were applied to SDS-PAGE and electroblotted on a PVDF membrane. Immunoblotting analysis was performed using chemiluminescence detection kit. The relative levels of immunoreactivity were determined by densitometry using the software ImageQuant 5.0 (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Samples were incubated with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-cyte-c (1 : 1000; BD PharMingen, Oxford, UK); rabbit anti-CB1R (1 : 500; Cayman Chemicals); rabbit anti-CB2R (1 : 1500; Cayman Chemicals); rabbit anti-bcl-2 (1 : 500; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); mouse anti-bax (1 : 2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); rabbit anti-hsp70 (1 : 500; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); mouse anti-hsp90 (1 : 1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); rat anti-Apaf-1 (1 : 2000; Millipore); rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (1 : 1000; Immunological Sciences); rabbit anti-phospho ERK1/2 (1 : 1000; Immunological Sciences, Rome, Italy); rabbit anti-Akt (1 : 1000; Cell Signaling); rabbit-anti-phospho Akt (1 : 500; Cell Signaling); mouse anti-JNK (1 : 1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); mouse anti-phospho-JNK (1 : 1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); mouse anti-p38 (1 : 1000; Cell Signaling); mouse anti-phospho-p38 (1 : 1000; Cell Signaling); and mouse anti-GAPDH (1 : 5000; Abcam). Densities of protein bands in the western blots were measured, and mean ratios between proteins and GAPDH were reported as percentage of control values.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from RNs using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Any remaining genomic DNA was eliminated with RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 1 μg of total RNA was used for RT reaction by using the SuperScript VILOTM cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). The following RT-PCR program was used: 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 85°C for 5 min. The expression of the different primers was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) using SensiMixTM SYBR Kit (Bioline, London, UK) as fluorescent dye to monitor cDNA amplification. The following PCR program was used: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 100 s. The primers used were: rat CB1R F (5′-GTTCCTCACAGCCATCGACA-3′); rat CB1R R (5′-CACATCAGGCAAAAGGCCAC-3′); rat CB2R F (5′-TGACCGCTGTTGACCGATAC-3′) and rat CB2R R (5′-CGAGAGGACCCACATGACAC-3′); and GAPDH F (5′-GGACCAGGTTGTCTCCTGTG-3′) and GAPDH R (5′-CATTGAGAGCAATGCCAGCC-3′). GAPDH was used as housekeeping gene for quantity normalization. Then, 1 μl of first strand of cDNA product was used for amplification (in triplicate) in a 20 μl reaction solution, containing 10 μl of iQTM SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and 1 μmol of each primer. The following PCR program was used: 95°C for 3 min, 40 amplification cycles at 95°C for 10 s, 56°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Fold change was determined by using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Co-immunoprecipitation

RNs were processed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Tx100, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% Protease Inhibitor Cocktails (Sigma)). The lysate was centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C (800 × g), supernatant was recovered and centrifuged for 30 min at 4°C (10 000 × g), and protein content was quantified by Bradford’s colorimetric assay (Bio-Rad).

The protein A-Agarose (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was washed three times in lysis buffer and incubated for 45 min at 4°C with 150 μg proteins and 500 μl of 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Tx100, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% Protease Inhibitor Cocktails (Sigma). After centrifugation for 3 min at 4°C (10 000 × g), 1 μg of anti-Apaf-1 was added to the supernatant and incubated overnight at 4°C. Beads were finally washed three times with lysis buffer and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were released by boiling in SB (2% SDS, 20% glycerol, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM dithiothreitol).

Percoll isolation

RNs collected from CTRL and SCH animals (at 7, 14, 21, and 60 days after injury) were incubated with a digestion buffer containing 1 × Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS; 14185, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1 mM L-Cystein (168149, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 30 mg/ml papain (P4762, Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.21% deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I; D5319, Sigma-Aldrich) in 37°C water bath for 30 min and then mechanically dissociated by trituration. Cells were washed two times with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and then resuspended in 8 ml of 25% of Stock Isotonic Percoll (SIP), prepared by mixing nine parts of Percoll (17-0891-01, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) with 1 part of 10 × HBSS, and overlaid with 2 ml of 1 × HBSS in 15 ml conical tubes. The tubes were centrifuged at 400 × g at 22°C for 25 min and then the whitish puffy layer (separated cells) was removed. After two washes in TBS, pelleted cells were collected and processed for flow cytometry analysis. The method employed in the present study was adapted from Juan et al.55

Flow cytometry

After Percoll isolation, cells were washed with PBS and then stained with Alexa-488 conjugated anti-NeuN specific antibody (1 : 100; Millipore) at 4°C for 15 min in order to selectively identify neuronal cells. For staining of dying cells, NeuN-positive cells were also stained with LIVE/DEAD dye (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Monza, Italy) at 4 °C for further 10 min and analyzed within 2 h. Flow cytometry analysis of RNs was performed on a FACSCanto cytofluorimeter (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Beam-walking test

Animals were examined with a fine-motor test paradigm (beam-walking test) and at 0 and 1, 3, 5, 7, 21, and 60 days after surgery. In the fine-motor behavior test, the locomotion of the rats was evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively using a beam-walking task with an elevated narrow beam (150 cm long × 2.5 cm wide). The worst score (‘0’) was given if the rat was unable to traverse the beam and could neither place the affected limbs on the horizontal surface nor maintain balance. A score of ‘1’ was given if the rat was unable to traverse the beam or to place the affected limbs on the horizontal surface of the beam but was able to maintain balance. A score of ‘2’ was given if the rat was unable to traverse the beam but placed the affected limbs on the horizontal surface of the beam and maintained balance. A score of ‘3’ was given if the rat used the affected limbs in less than half of its steps along the beam. A score of ‘4’ was given if the rat traversed the beam and used the affected limbs to aid with >50% of its steps along the beam.

A score of ‘5’ was given if the rat traversed the beam and used the affected limbs to aid with <50% of its steps along the beam. A score of ‘6’ was given if the rat traversed the beam normally with no more than two-foot slips. The week before, surgery animals were trained to run the narrow beam for a food reward once daily, 5 days per week. All the animals in all groups underwent the motor behavior test to ensure that their performance score before surgery (day 0) was 6.

CatWalk

To assess the effects of SCI on locomotor gait dynamics, we used the catWalk gait analysis system (version 8.1; Noldus, Wageningen, The Nederlands) as previously described.56 Briefly, this system consists of a glass runway with customized lighting that is video recorded as the animals traverse the runway. From these videos, the system determines the percentage of usage by each paw and the intensity of footprints during maximum paw contact at every step. Animals were trained for 5 min daily in the week preceding lesion. Rats were trained to run across the runway consistently for 5 days before testing, with each training session consisting of 3 runs across the platform. After that animals were tested on days 0, 7, 21, and 60 postoperatively. At each experimental time point, three runs for each animal were recorded from below the glass by a digital video camera.

Coordination and different individual paw parameters were assessed to quantify functional recovery after treatment. The following parameters were considered:

-

Regularity index (expressed in percentages): index of the number of normal step sequence patterns relative to the total number of paw placements. It is a percent index and is used as a measure of the degree of interlimb coordination during the gait cycle;

-

Paw length, width, and area (in millimeter) of the forepaw during the stance phase reflecting the total print size of the forepaw;

-

maximal area (expressed in square millimeter): maximal contact area of the forepaw at the moment of its maximal floor contact during stance.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as mean±S.D. Differences between means were analyzed using one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism-5 software (GraphPAD Software for Science, San Diego, CA, USA) with significance set at P<0.05.

Abbreviations

- SCI:

-

spinal cord injury

- SCH:

-

spinal cord hemisection

- ECS:

-

endocannabinoid system

- CB1R:

-

cannabinoid receptor type 1

- CB2R:

-

cannabinoid receptor type 2

- RSN:

-

rubrospinal neuron

- RN:

-

red nucleus

- cyt-c:

-

cytochrome c

- qPCR:

-

quantitative real-time PCR

- FB:

-

Fast-blue

- JWH:

-

JWH-015

- SR2:

-

SR144528

- HCb:

-

hemicerebellectomy

- TBI:

-

traumatic brain injury

- NO:

-

nitric oxide

- nNOS:

-

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- JNK:

-

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- PD:

-

PD98059

- PI3K:

-

phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase

References

Binkofski F, Seitz RJ, Arnold S, Classen J, Benecke R, Freund HJ . Thalamic metabolism and corticospinal tract integrity determine motor recovery in stroke. Ann Neurol 1996; 39: 460–470.

Block F, Dihne M, Loos M . Inflammation in areas of remote changes following focal brain lesion. Prog Neurobiol 2005; 75: 342–365.

Little JW, Halar E . Temporal course of motor recovery after Brown-Sequard spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia 1985; 23: 39–46.

Roth EJ, Park T, Pang T, Yarkony GM, Lee MY . Traumatic cervical Brown-Sequard and Brown-Sequard-plus syndromes: the spectrum of presentations and outcomes. Paraplegia 1991; 29: 582–589.

Alger BE, Kim J . Supply and demand for endocannabinoids. Trends Neurosci 2011; 34: 304–315.

Piomelli D . The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003; 4: 873–884.

Di Marzo V . Endocannabinoids: synthesis and degradation. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2008; 160: 1–24.

Amantea D, Spagnuolo P, Bari M, Fezza F, Mazzei C, Tassorelli C et al. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system by focal brain ischemia in the rat is involved in neuroprotection afforded by 17beta-estradiol. FEBS J 2007; 274: 4464–4775.

Panikashvili D, Simeonidou C, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, Breuer A, Mechoulam R et al. An endogenous cannabinoid (2-AG) is neuroprotective after brain injury. Nature 2001; 413: 527–531.

Viscomi MT, Oddi S, Latini L, Pasquariello N, Florenzano F, Bernardi G et al. Selective CB2 receptor agonism protects central neurons from remote axotomy-induced apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt pathway. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 4564–4570.

Chiurchiu V, Cencioni MT, Bisicchia E, De Bardi M, Gasperini C, Borsellino G et al. Distinct modulation of human myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells by anandamide in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2013; 73: 626–636.

Arevalo-Martin A, Vela JM, Molina-Holgado E, Borrell J, Guaza C . Therapeutic action of cannabinoids in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 2511–2516.

Velayudhan L, Van Diepen E, Marudkar M, Hands O, Suribhatla S, Prettyman R et al. Therapeutic potential of cannabinoids in neurodegenerative disorders: a selective review. Curr Pharm Des 2013; 20: 2218–2230.

Garcia-Ovejero D, Arevalo-Martin A, Petrosino S, Docagne F, Hagen C, Bisogno T et al. The endocannabinoid system is modulated in response to spinal cord injury in rats. Neurobiol Dis 2009; 33: 57–71.

Arevalo-Martin A, Garcia-Ovejero D, Molina-Holgado E . The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol reduces lesion expansion and white matter damage after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis 2010; 38: 304–312.

Arevalo-Martin A, Garcia-Ovejero D, Sierra-Palomares Y, Paniagua-Torija B, Gonzalez-Gil I, Ortega-Gutierrez S et al. Early endogenous activation of CB1 and CB2 receptors after spinal cord injury is a protective response involved in spontaneous recovery. PLoS One 2012; 7: e49057.

Adhikary S, Li H, Heller J, Skarica M, Zhang M, Ganea D et al. Modulation of inflammatory responses by a cannabinoid-2-selective agonist after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 2417–2427.

Egan DA, Flumerfelt BA, Gwyn DG . Axon reaction in the red nucleus of the rat. Perikaryal volume changes and the time course of chromatolysis following cervical and thoracic lesions. Acta Neuropathol 1977; 37: 13–19.

Barron KD, Banerjee M, Dentinger MP, Scheibly ME, Mankes R . Cytological and cytochemical (RNA) studies on rubral neurons after unilateral rubrospinal tractotomy: the impact of GM1 ganglioside administration. J Neurosci Res 1989; 22: 331–337.

Kwon BK, Liu J, Messerer C, Kobayashi NR, McGraw J, Oschipok L et al. Survival and regeneration of rubrospinal neurons 1 year after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 3246–3251.

Liu PH, Wang YJ, Tseng GF . Close axonal injury of rubrospinal neurons induced transient perineuronal astrocytic and microglial reaction that coincided with their massive degeneration. Exp Neurol 2003; 179: 111–126.

Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G . Mitochondria: master regulators of danger signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13: 780–788.

Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE, Didelot C, Kroemer G . Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 2006; 13: 1423–1433.

Janicke RU, Sprengart ML, Wati MR, Porter AG . Caspase-3 is required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 9357–9360.

Raghupathi R, Strauss KI, Zhang C, Krajewski S, Reed JC, McIntosh TK . Temporal alterations in cellular Bax:Bcl-2 ratio following traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma 2003; 20: 421–435.

Xu M, Ng YK, Leong SK . Neuroprotective and neurodestructive functions of nitric oxide after spinal cord hemisection. Exp Neurol 2000; 161: 472–480.

Viscomi MT, Molinari M . Remote neurodegeneration: multiple actors for one play. Mol Neurobiol 2014; 163: 1402–1410.

Tetzlaff W, Alexander SW, Miller FD, Bisby MA . Response of facial and rubrospinal neurons to axotomy: changes in mRNA expression for cytoskeletal proteins and GAP-43. J Neurosci 1991; 11: 2528–2544.

Jenkins R, Tetzlaff W, Hunt SP . Differential expression of immediate early genes in rubrospinal neurons following axotomy in rat. Eur J Neurosci 1993; 5: 203–209.

Shohami E, Cohen-Yeshurun A, Magid L, Algali M, Mechoulam R . Endocannabinoids and traumatic brain injury. Br J Pharmacol 2011; 163: 1402–1410.

Ashoton JC, Rahman RM, Nair SM, Sutherland BA, Glass M, Appleton I . Cerebral hypoxia-ischemia and middle cerebral artery occlusion induce expression of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in the brain. Neurosci Lett 2007; 412: 114–117.

Oddi S, Latini L, Viscomi MT, Bisicchia E, Molinari M, Maccarrone M . Distinct regulation of nNOS and iNOS by CB2 receptor in remote delayed neurodegeneration. J Mol Med 2012; 90: 371–387.

Atwood BK, Mackie K . CB2: a cannabinoid receptor with an identity crisis. Br J Pharmacol 2010; 160: 467–479.

Onaivi ES . Commentary: Functional neuronal CB2 cannabinoid receptors in the CNS. Curr Neuropharmacol 2011; 9: 205–208.

Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Gu S, Liu QR . CNS effects of CB2 cannabinoid receptors: beyond neuro-immuno-cannabinoid activity. J Psychopharmacol 2012; 26: 92–103.

Feringa ER, McBride RL, Pruitt JN . Loss of neurons in the red nucleus after spinal cord transection. Exp Neurol 1988; 100: 112–120.

Mori F, Himes BT, Kowada M, Murray M, Tessler A . Fetal spinal cord transplants rescue some axotomized rubrospinal neurons from retrograde cell death in adult rats. Exp Neurol 1997; 143: 45–60.

Zhou L, Connors T, Chen DF, Murray M, Tessler A, Kambin P et al. Red nucleus neurons of Bcl-2 over-expressing mice are protected from cell death induced by axotomy. Neuroreport 1999; 10: 3417–3421.

McBride RL, Feringa ER, Garver MK, Williams JK . Prelabeled red nucleus and sensorimotor cortex neurons of the rat survive 10 and 20 weeks after spinal cord transection. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1989; 48: 568–576.

Fukuoka T, Miki K, Yoshiya I, Noguchi K . Expression of beta-calcitonin gene-related peptide in axotomized rubrospinal neurons and the effect of brain derived neurotrophic factor. Brain Res 1997; 767: 250–258.

Carter LM, McMahon SB, Bradbury EJ . Delayed treatment with chondroitinase ABC reverses chronic atrophy of rubrospinal neurons following spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 2011; 228: 149–156.

Thuret S, Moon LD, Gage FH . Therapeutic interventions after spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006; 7: 628–643.

Kobayashi NR, Fan DP, Giehl KM, Bedard AM, Wiegand SJ, Tetzlaff W . BDNF and NT-4/5 prevent atrophy of rat rubrospinal neurons after cervical axotomy, stimulate GAP-43 and Talpha1-tubulin mRNA expression, and promote axonal regeneration. J Neurosci 1997; 17: 9583–9595.

Kwon BK, Liu J, Lam C, Plunet W, Oschipok LW, Hauswirth W et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene transfer with adeno-associated viral and lentiviral vectors prevents rubrospinal neuronal atrophy and stimulates regeneration-associated gene expression after acute cervical spinal cord injury. Spine 2007; 32: 1164–1173.

Liu Y, Himes BT, Murray M, Tessler A, Fischer I . Grafts of BDNF-producing fibroblasts rescue axotomized rubrospinal neurons and prevent their atrophy. Exp Neurol 2002; 178: 150–164.

Maccarrone M, Finazzi-Agro A . The endocannabinoid system, anandamide and the regulation of mammalian cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 2003; 10: 946–955.

Cohen-Yeshurun A, Trembovler V, Alexandrovich A, Ryberg E, Greasley PJ, Mechoulam R et al. N-arachidonoyl-L-serine is neuroprotective after traumatic brain injury by reducing apoptosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 1768–1777.

Molina-Holgado F, Pinteaux E, Heenan L, Moore JD, Rothwell NJ, Gibson RM . Neuroprotective effects of the synthetic cannabinoid HU-210 in primary cortical neurons are mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci 2005; 28: 189–194.

Howlett AC . Cannabinooid receptor signaling. Hand Exp Pharmacol 2005; 168: 53–79.

Elliott MB, Tuma RF, Amenta PS, Barbe MF, Jallo JI . Acute effects of a selective cannabinoid-2 receptor agonist on neuroinflammation in a model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2011; 28: 973–981.

Zhang M, Martin BR, Adler MW, Razdan RK, Jallo JI, Tuma RF . Cannabinoid CB(2) receptor activation decreases cerebral infarction in a mouse focal ischemia/reperfusion model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007; 27: 1387–1396.

Rossignol S, Barriere G, Alluin O, Frigon A . Re-expression of locomotor function after partial spinal cord injury. Physiology 2009; 24: 127–139.

Rossignol S, Frigon A . Recovery of locomotion after spinal cord injury: some facts and mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci 2011; 34: 413–440.

Viscomi MT, D’Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Latini L, Bisicchia E, Nazio F et al. Stimulation of autopghagy by rapamycin protects neurons from remote degeneration after acute focal brain damage. Autophagy 2012; 8: 222–235.

Juan WS, Li HW, Chen YH, Chen HY, Hung YC, Tai SH et al. Optimal percoll concentration facilitates flow cytometric analysis for annexin V/propidium iodine-stained ischemic brain tissues. Cytometry A 2012; 81: 400–408.

Hamers FP, Koopmans GC, Joosten EA . CatWalk-assisted gait analysis in the assessment of spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2006; 23: 537–548.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente; to M Molinari); by Wings for Life Spinal Cord Research Foundation (to MTV); partially by International Foundation for Research in Paraplegia (IFP) (to MTV); by program Young Researchers of Italian Ministry of Health (GR10.184; to MTV); and by PRIN 2010-2011 (to M Maccarrone). We thank Professor G Bernardi for his continuous support and encouragement. The professional editorial work of Blue Pencil Science is also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by A Verkhratsky

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website

Rights and permissions

Cell Death and Disease is an open-access journal published by Nature Publishing Group. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Latini, L., Bisicchia, E., Sasso, V. et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor (CB2R) stimulation delays rubrospinal mitochondrial-dependent degeneration and improves functional recovery after spinal cord hemisection by ERK1/2 inactivation. Cell Death Dis 5, e1404 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.364

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.364

This article is cited by

-

Early Life Social Stress Causes Sex- and Region-Dependent Dopaminergic Changes that Are Prevented by Minocycline

Molecular Neurobiology (2022)

-

Systematic review of the impact of cannabinoids on neurobehavioral outcomes in preclinical models of traumatic and nontraumatic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Autophagy Inhibition Favors Survival of Rubrospinal Neurons After Spinal Cord Hemisection

Molecular Neurobiology (2017)