Abstract

Determinants of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16 serological conversion and persistence were assessed in a population-based cohort of 10 049 women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Serologic responses to HPV-16 were measured in 7986 women by VLP-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at both study enrolment (1993/94) and at 5–7 years of follow-up. Seropositive women were defined as ⩾5 standard deviations above the mean optical density obtained for studied virgins at enrolment (n=573). Seroconnversion (n=409), persistence (n=675), and clearance (n=541) were defined based on enrolment and follow-up serology measurements. Age-specific distributions revealed that HPV-16 seroconversion was highest among 18- to 24-year-old women, steadily declining with age; HPV-16 seropersistence was lowest in women 65+ years. In age-adjusted multivariate logistic regression models, a 10-fold risk increase for HPV-16 seroconversion was associated with HPV-16 DNA detection at enrolment and follow-up; two-fold risk of seroconversion to HPV-16 was associated with increased numbers of lifetime and recent sexual partners and smoking status. Determinants of HPV-16 seropersistence included a 1.5-fold risk increase associated with having one sexual partner during follow-up, former oral contraceptive use, and a 3-fold risk increase associated with HPV-16 DNA detection at both enrolment and follow-up. Higher HPV-16 viral load at enrolment was associated with seroconversion, and higher antibody titres at enrolment were associated with seropersistence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Most genital human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are transient: within 2 years of incident infection, HPV DNA becomes undetectable in approximately 90% of women (Ho et al, 1995). Moreover, not all women infected with HPV seroconvert; only about half of all HPV DNA-positive women test positive for corresponding type-specific antibodies using available assays (Kirnbauer et al, 1994; Le Cann et al, 1995). For those women who have seroconverted, however, detection of serum antibodies to HPV capsids is a valid marker of current and past type-specific HPV exposure (Wideroff et al, 1995, 1999; Carter et al, 1996; Sasagawa et al, 1998; Touze et al, 2001).

We previously reported population-based seroprevalence of HPV-16, -18, -31, and -45 in our 10 000 women population-based study in Costa Rica at enrolment; we confirmed the waning detection of HPV antibodies with age and the determinants of seroprevalence to include increasing lifetime number of sexual partners and smoking (Wang et al, 2003), as similarly reported in other prevalence studies (Stone et al, 2002; Nonnenmacher et al, 2003).

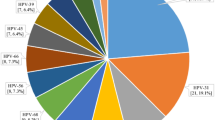

To extend our cross-sectional findings, we have now completed HPV-16 serology measurements at a second time point, after 5–7 years of follow-up. Human papillomavirus 16 was selected because it accounts for the majority of cervical cancers worldwide (Munoz et al, 2003) and is the focus of immunology and vaccinology research (Lowy and Frazer, 2003). To further our understanding of HPV serology in the natural history of cervical cancer, we report here the epidemiologic characteristics and determinants of HPV-16 serologic conversion and persistence in our Guanacaste, Costa Rica cohort.

Methods

Study population

This study was conducted in the population-based cohort of 10 049 women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. As previously described, study enrolment was conducted in 1993–94 with approval from the NCI and local institutional review boards (Herrero et al, 1997; Hildesheim et al, 2001; Bratti et al, 2004). Briefly, the cohort was a representative sample of the adult female population in Guanacaste, Costa Rica in 1993–94. Of 10 738 women eligible for the study, 10 049 were interviewed (94%); refusals were women who did not show up for their appointment despite multiple invitations. At enrolment, study participants completed a risk factor questionnaire that addressed demographic characteristics and behavioural and reproductive practices. Follow-up of the cohort was conducted for 5–7 years until cohort exit, which began in 2000. For the present analysis, follow-up data were available for 8084 women; the median length of follow-up was 6.4 years. In the present analysis, a histologic diagnosis of CIN3 or cancer during follow-up (n=75) was considered the reference standard of serious, newly diagnosed high-grade disease. Plasma specimens collected from women at enrolment and at the end of follow-up (concurrently at the time of diagnosis for cases) were used for measurement of serologic responses to HPV-16. Of the 10 049 women enrolled in the cohort, serology results from enrolment specimens were obtained for 9951 women. Of the 8084 women selected for follow-up (women with hysterectomies or prevalent high-grade neoplasia were not followed) (Bratti et al, 2004), plasma samples were obtained from 8058 women. However, of the 8058 women with plasma at follow-up, 72 women did not have plasma at enrolment. Our final analytic population thus included 7986 women for whom plasma was available at both time points.

Serological measurements

Plasma samples collected at study enrolment and at the end of follow-up were tested for anti-HPV L1 antibodies (IgG) at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions by a VLP-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for HPV-16. Serology measurements were conducted as previously described (Wang et al, 2003). Briefly, each batch comprised approximately 2000–3000 specimens, including intra- and interbatch reliability repeat specimens and random samples of 200 virgins in the study population, which permitted the calculation of batch-specific serology cut-points (see below).

Human papillomavirus DNA testing

Cervical cytologic specimens collected using a Dacron swab at enrolment and follow-up were tested for HPV DNA using L1 MY09/MY11 consensus primer methods, with TaqGold polymerase and dot-blot typing, as previously described (Herrero et al, 2000). The results for HPV-16 testing were available for 7367 women included in the present analysis, because virgins did not undergo pelvic examinations at enrolment.

Statistical methods

Consistent with our previous analysis, serology results were dichotomised as antibody positive or negative (Wang et al, 2003). Women whose mean optical density (OD) measurements were five standard deviations above that obtained for the concurrently tested virgins (minus outliers in the virgin OD distribution) were categorised as seropositive. All other women below the five standard deviation cut-point were defined as seronegative. This definition of seronegative women included, at enrolment, 3110 women above and 5307 women below one standard deviation of study virgins; at follow-up, this definition included 1470 women above and 5495 women below one standard deviation of study virgins. The cutoff was calculated independently for each test batch, by comparison to the distribution of the values obtained for the concurrently tested virgins in that batch (n=200). To demonstrate that our results were robust, we also compared seropositive women to seronegative women, defined as less than one standard deviation from studied virgins.

Defining serologic outcomes

The enrolment population was first dichotomised as HPV-16 seropositive (n=1534) and seronegative (n=8417). Of the 1216 (79%) HPV-16 seropositive women with follow-up data, 675 (55.5%) remained seropositive at follow-up and 541 (44.5%) tested seronegative (Table 1). Of the 6770 (80%) HPV-16 seronegative women at enrolment with follow-up data, 409 (6%) seroconverted and 6361 (94%) remained seronegative (Table 1). We identified determinants of seroconversion by comparing the 409 women who seroconverted to the 6361 who remained seronegative. Likewise, we identified determinants of seropersistence by comparing the 675 women who remained seropositive at follow-up to the 541 who became seronegative.

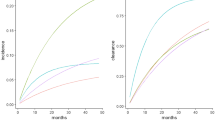

Age-specific distributions of seroconversion, serologic persistence, and serologic clearance were graphically compared with age category in years (18–24, 25–29, 30–44, 45–64, 65+ years). Age was calculated as the woman's age at the midpoint of her follow-up.

Determinants of serologic status

All HPV cofactors reported previously in Costa Rica (Hildesheim et al, 2001) were thoroughly investigated with regard to serologic outcomes. Specifically, univariate associations for both outcomes (seroconversion and seropersistence) were assessed for the following behavioural and reproductive variables assessed at enrolment and follow-up via questionnaire: number of sexual partners (lifetime at enrolment, and recent, defined as during the follow-up period and thus includes both previous and new partners), use of oral contraceptives (OCs) (never, former, current), smoking status (never, former, current), early age at first intercourse (defined as <16 years), number of live births and number of pregnancies (lifetime at enrolment and recent, defined as during the follow-up period), years between menarche and sexual debut, and self-reported sexually transmitted diseases. For smoking and OC use, a combined variable was constructed from enrolment and follow-up data (e.g. enrolment/follow-up – never/never, former/former, current/current, never/current, current/former, former/current). Odds ratio estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained to assess the magnitude and statistical significance of the associations between these variables and HPV serostatus. Presence of HPV-16 DNA at enrolment and follow-up was also assessed considering all combinations for DNA status (e.g. enrolment/follow-up – negative/negative, negative/positive, positive/negative, positive/positive).

We assessed HPV-16 semiquantitative viral load and the OD for serological measurement at enrolment as potential determinants of HPV seroconversion and seropersistence. Specifically, we assessed whether women with higher OD measurements at enrolment were more likely to remain seropositive at follow-up, and whether higher HPV-16 viral load at enrolment, as measured by signal strength from PCR, was associated with seroconversion or seropersistence.

Variables independently and statistically significantly associated with seroconversion or seropersistence in our univariate analyses were included in our final multivariate models; they included number of lifetime sexual partners reported at enrolment (1, 2–3, 4+), number of sexual partners during follow-up (0, 1, 2+), smoking (never/never, never/current, current/current, current/former, former/former, former/current), OC use (never/never, never/current, current/current, current/former, former/former, former/current), and HPV-16 DNA status (positive/positive, positive/negative, negative/positive, negative/negative) as measured by PCR. Our final model also adjusted for age at the midpoint of the woman's follow-up (years), and serology batch. We excluded women who remained virgins throughout the duration of study follow-up (n=273).

Finally, the age-adjusted association between HPV-16 DNA and serological status among the 75 women with a CIN3/cancer diagnosis during study follow-up was assessed (odds ratio and 95% CI). For these cases, the follow-up testing was carried out at the time of diagnosis before treatment. CIN3/cancers diagnosed at enrolment were censored for follow-up and did not have a second time point for which serology measurements were made; thus, they were excluded from all analyses. Statistical analyses were conducted on SAS 8.2 for Windows and STATA 7.0.

Results

Seroprevalence of HPV-16 at both cross-sectional time points (enrolment in 1993–94, and follow-up in 2000) was 15%. In all, 55% (675 of 1216) of women seropositive at enrolment remained seropositive for HPV-16 at follow-up, while 6% (409 of 6770) of initially HPV-16 seronegative women were seropositive at the time of follow-up. As shown in Figure 1, serologic status varied by age. Of women seronegative at enrolment, seroconversion was highest in women 18–24 years old and steadily declined with increasing age. Of women seropositive at enrolment, HPV-16 serologic persistence was above 50% for all age groups except in women 65 years and older.

Determinants of HPV-16 seroconversion

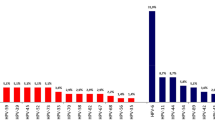

Univariate analyses for determinants of HPV-16 seroconversion, compared to women who remained seronegative, revealed a number of potential determinants, which were subsequently included in the final multivariate logistic regression model. After adjustment for age and serology batch, and excluding women who remained virgins for the duration of the cohort study, two or more lifetime number of sexual partners and one or more sexual partner (not necessarily new partners) during study follow-up were statistically significantly associated with an increased risk for seroconversion (Table 2). It is important to note that when stratified by lifetime number of sexual partners, one or more sexual partners during study follow-up remained associated with risk for seroconversion; likewise, when stratified by number of sexual partners during follow-up, two or more lifetime number of sexual partners reported at enrolment also remained significantly associated with risk for seroconversion. Compared to never smokers, a 2.8-fold increase in risk is observed for women who were smokers at enrolment and former smokers at the time of follow-up; no other category of smoking increased risk for seroconversion. Finally, women HPV-16 DNA positive at enrolment and at follow-up possessed the highest level of risk for HPV-16 seroconversion with an odds ratio of 10.0 (95% CI: 4.5–22.2), followed by a 6.4-fold risk increase for women who were initially HPV DNA negative but positive at follow-up, and a three-fold risk increase for women who were HPV DNA positive at enrolment and negative at follow-up; all were statistically significant.

Determinants of HPV-16 seropersistence

Univariate analyses of women with serologic persistence, compared to women who were seronegative at follow-up, demonstrated recent number of sexual partners and former OC use as possible risk factors for seropersistence. After adjustment for age and serology batch, and excluding women who remained virgins for the entire study, multivariate analyses revealed that women reporting one sexual partner during follow-up and those reporting former OC use at both enrolment and follow-up had a 1.5-fold statistically significant increase in risk for serologic persistence (Table 3). In addition, women HPV-16 DNA positive at both enrolment and follow-up had a 3.3-fold increase in risk for HPV-16 seropersistence followed by a 2.2-fold increase in risk for women HPV-16 DNA positive at enrolment but negative at follow-up. Further stratification by age (<30 and ⩾30 years) did not alter these results.

HPV-16 viral load and OD measurements

Increasing HPV-16 viral load at enrolment as measured by qualitative PCR signal strength (weak vs strong, as assessed by two observers with adjudication in case of disagreement) was also associated with a significant higher odds ratio for HPV-16 seroconversion. Odds ratios were 3.0 (95% CI: 1.5–6.0) and 6.2 (95% CI: 3.5–11.1) for weak and strong HPV-16 PCR signal strengths, respectively. Viral load did not appear to modify the risk of seropersistence among HPV-16-positive women, with odds ratios of 2.7 (95% CI: 1.2–6.4) and 2.2 (95% CI: 1.1–4.2) for weak and strong signal strengths, respectively. Further stratification by age also did not reveal differences. Further investigation of determinants of serologic persistence also revealed that of women seropositive at enrolment (e.g. five standard deviations above the set cut-point), women with the highest mean OD measures at enrolment were most likely to remain seropositive at follow-up, as defined by the same cut-point. Specifically, 80% of women with the highest quartile of mean OD seropersisted; these women possessed a 12.7-fold increase in risk for seropersistence when compared to seropositive women in the lowest quartile. In all, 5.8- and 2.0-fold increases in risk for seropersistence were observed for women in the third and second quartiles of mean OD, respectively. In the third quartile of mean OD, 69% seropersisted, and in the second quartile 44% seropersisted.

Association between serologic status and CIN3/cancer

Finally, we observed significant associations between serologic status and disease outcome of CIN3/cancer diagnosed during follow-up as shown in Table 4. Compared to women who were HPV-16 seronegative at both time points, women who seropersisted or seroconverted were at elevated risk for CIN3/cancer. Women who became seronegative at follow-up were not at significant increase in risk for CIN3/cancer. When restricted to HPV-16 DNA-positive women as measured by PCR, risk associations between serology and disease were no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

In the present study, serologic status was a dynamic result of seroconversion and clearance; only half of all seropositive women were seropositive at both time points. In our previous cross-sectional study, seroprevalence peaked at 35–44 years old (Wang et al, 2003); in the present analysis, seropersistence was also highest in this age group. Seroconversion was highest in women 18–24 years old and steadily declined with age. This pattern mirrored HPV DNA age curves we reported previously, with a peak at youngest age groups and declining with age (Wang et al, 2003). Although of interest, detailed assessment of HPV DNA and serological status particularly in older age groups could not be assessed due to small numbers in these older age groups. Nevertheless, age-specific patterns of HPV-16 serologic conversion and persistence support the known waning of serological response with age and time.

In women identified as HPV-16 DNA positive at enrolment, less than half were HPV-16 seropositive at enrolment, consistent with previous studies (Carter et al, 2000). Although an additional 13% of seronegative women at enrolment were subsequently seropositive at follow-up, this could be the result of either HPV-16 infection identified at enrolment or from a subsequent infection (e.g. with the same or different HPV-16 variant).

Determinants of seroconversion at follow-up were similar to the determinants of seroprevalence we reported previously in our cross-sectional analysis (Wang et al, 2003), which were generally consistent with other populations (Stone et al, 2002; Nonnenmacher et al, 2003); recent and lifetime number of sexual partners and smoking behaviour remained associated with seroconversion. Curiously, increased risk appeared to be especially elevated among women who were current smokers at enrolment but former smokers at the time of follow-up, potentially suggesting temporality related to smoking behaviour, its concurrence with HPV exposure, and subsequent detection of antibodies. As expected, the highest risk for seroconversion was observed for women HPV-16 DNA positive both at enrolment and at follow-up. Women HPV-16 DNA positive at enrolment but negative at follow-up exhibited the next highest level of risk for seroconversion, supporting the notion that HPV antibody detection is a marker of past infection.

Determinants for seropersistence included having one sexual partner during the follow-up period and former OC use. For reasons that are not clear, having two partners during follow-up was not associated with seropersistence; continued HPV exposure (and possibly re-exposure) with the same HPV type and resultant antigenic stimulation is to be investigated in a more refined analysis of HPV DNA typing for all years of follow-up. We also found that for seropositive women, a higher OD at enrolment was associated with seropersistence at follow-up, consistent with a previous study in which HPV antibodies persisted when initial levels were high or when there was continued exposure (Ho et al, 2004). It is unclear why former OC use was associated with increased risk for seropersistence. Although former OC users were older, our analysis was adjusted for age, and separate analyses stratified by age did not demonstrate differences; former OC use was not related to mean OD levels.

Although IgG seroconversion against HPV-16 has been reported within 6–12 months of infection (Wikstrom et al, 1995; Carter et al, 2000), the duration of serologic detection (e.g. being seropositive) remains unclear (Stone et al, 2002). Reported to be high over a long period of time (van Doornum et al, 1998), serology measures are likely to be confounded by repeated exposure to HPV-16 (Onda et al, 2003). Persistence of HPV-16 antibodies has been found for 7–13 years (Shah et al, 1997) and for 4 years in a study of 1656 pregnant women who demonstrated stable antibody levels (af Geijersstam et al, 1998). We defined seropersistence as two high positive antibody measurements at enrolment and at follow-up, that is, for a median duration of over 6 years. Because serology was only assessed at two time points, we could not assess the duration of the serologic response or its determinants. Further investigation of multiple, longitudinal measurements of HPV infection assessed by both serology and DNA testing during the 5–7 years of follow-up is likely to provide additional clues regarding seropersistence.

Several studies have reported a 2–3-fold magnitude of risk for cervical cancer for HPV seropositive women, compared to seronegative women (Nonnenmacher et al, 1995, 1996; Chua et al, 1996; Wideroff et al, 1996; Dillner et al, 1997; Sigstad et al, 2002). In this study, we found that seropositive women who are seronegative by follow-up are not at increased risk for CIN3/cancer. On the contrary, women who seroconvert or are seropersistent possessed the highest risk for CIN3/cancer. However, the lack of association when restricted to HPV-16 DNA-positive women suggests the overwhelming association between HPV DNA and disease.

Limitations of our study include the necessity for a high cutoff (five standard deviations above mean for studied virgins) to define HPV-16 seropositive women. Because VLP ELISAs are still prone to misclassification including false positives, we chose to define HPV-16 seropositive women stringently, thus probably misclassifying some HPV-16 seropositive women (seroconverters or seropersisters) as seronegative and biasing our results towards the null. However, we attempted to measure the accuracy of our definition of seropersistence by a small subset of approximately 1500 women, and measurements were conducted 1 year after enrolment. While the majority of women defined as seropersistent (based on enrolment and 5–7 years of follow-up) were also seropositive at 1 year after enrolment, approximately 10% were not. This probably reflects misclassification in our definition of seropersistence and might also have further biased our results towards the null.

To our knowledge, this is the largest population-based seroprevalence study of HPV-16 with follow-up serology data. Our subjects were representative of the adult female population of Guanacaste, Costa Rica and our results provide a detailed description of serologic status in this and population behavioural factors likely to influence long-term serologic status. The known waning of HPV antibody detection with age is confirmed, attributed to both decline in seroconversion and seropersistence; these age-specific data may be relevant to future plans for HPV vaccination. Because antibody titres after natural infection are lower than those following vaccination, these immunologic responses should be distinguishable. Future analysis assessing longitudinal HPV DNA status in relation to serologic status will be important for clarifying the role that transient and persistent HPV infections play in initiating and sustaining a humoral immune response.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

af Geijersstam V, Kibur M, Wang Z, Koskela P, Pukkala E, Schiller J, Lehtinen M, Dillner J (1998) Stability over time of serum antibody levels to human papillomavirus type 16. J Infect Dis 177: 1710–1714

Bratti MC, Rodriguez AC, Schiffman M, Hildesheim A, Morales J, Alfaro M, Guillen D, Hutchinson M, Sherman ME, Eklund C, Schussler J, Buckland J, Morera LA, Cardenas F, Barrantes M, Perez E, Cox TJ, Burk RD, Herrero R (2004) Description of a seven-year prospective study of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia among 10 000 women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica (Descripcion de un estudio prospectivo de siete anos sobre la infeccion por el virus del papiloma humano y el cancer cervicouterino en 10 000 mujeres de Guanacaste, Costa Rica). Rev Panam Salud Publica 15: 75–89

Carter JJ, Koutsky LA, Hughes JP, Lee SK, Kuypers J, Kiviat N, Galloway DA (2000) Comparison of human papillomavirus types 16, 18, and 6 capsid antibody responses following incident infection. J Infect Dis 181: 1911–1919

Carter JJ, Koutsky LA, Wipf GC, Christensen ND, Lee SK, Kuypers J, Kiviat N, Galloway DA (1996) The natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 capsid antibodies among a cohort of university women. J Infect Dis 174: 927–936

Chua KL, Wiklund F, Lenner P, Angstrom T, Hallmans G, Bergman F, Sapp M, Schiller J, Wadell G, Hjerpe A, Dillner J (1996) A prospective study on the risk of cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia among healthy subjects with serum antibodies to HPV compared with HPV DNA in cervical smears. Int J Cancer 68: 54–59

Dillner J, Lehtinen M, Bjorge T, Luostarinen T, Youngman L, Jellum E, Koskela P, Gislefoss RE, Hallmans G, Paavonen J, Sapp M, Schiller JT, Hakulinen T, Thoresen S, Hakama M (1997) Prospective seroepidemiologic study of human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for invasive cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 89: 1293–1299

Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Bratti C, Sherman ME, Hutchinson M, Morales J, Balmaceda I, Greenberg MD, Alfaro M, Burk RD, Wacholder S, Plummer M, Schiffman M (2000) Population-based study of human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia in rural Costa Rica. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 464–474

Herrero R, Schiffman MH, Bratti C, Hildesheim A, Balmaceda I, Sherman ME, Greenberg M, Cardenas F, Gomez V, Helgesen K, Morales J, Hutchinson M, Mango L, Alfaro M, Potischman NW, Wacholder S, Swanson C, Brinton LA (1997) Design and methods of a population-based natural history study of cervical neoplasia in a rural province of Costa Rica: the Guanacaste Project. Rev Panam Salud Publica 1: 362–375

Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Castle PE, Wacholder S, Bratti MC, Sherman ME, Lorincz AT, Burk RD, Morales J, Rodriguez AC, Helgesen K, Alfaro M, Hutchinson M, Balmaceda I, Greenberg M, Schiffman M (2001) HPV co-factors related to the development of cervical cancer: results from a population-based study in Costa Rica. Br J Cancer 84: 1219–1226

Ho GY, Burk RD, Klein S, Kadish AS, Chang CJ, Palan P, Basu J, Tachezy R, Lewis R, Romney S (1995) Persistent genital human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for persistent cervical dysplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 1365–1371

Ho GY, Studentsov YY, Bierman R, Burk RD (2004) Natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particle antibodies in young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13: 110–116

Kirnbauer R, Hubbert NL, Wheeler CM, Becker TM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT (1994) A virus-like particle enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum antibodies in a majority of women infected with human papillomavirus type 16. J Natl Cancer Inst 86: 494–499

Le Cann P, Touze A, Enogat N, Leboulleux D, Mougin C, Legrand MC, Calvet C, Afoutou JM, Coursaget P (1995) Detection of antibodies against human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 virions by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant HPV 16 L1 capsids produced by recombinant baculovirus. J Clin Microbiol 33: 1380–1382

Lowy DR, Frazer IH (2003) Chapter 16: Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 31: 111–116

Munoz N, Bosch FX, De Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ (2003) Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 348: 518–527

Nonnenmacher B, Hubbert NL, Kirnbauer R, Shah KV, Munoz N, Bosch FX, De Sanjose S, Viscidi R, Lowy DR, Schiller JT (1995) Serologic response to human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) virus-like particles in HPV-16 DNA-positive invasive cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III patients and controls from Colombia and Spain. J Infect Dis 172: 19–24

Nonnenmacher B, Kruger KS, Svare EI, Scott JD, Hubbert NL, van den Brule AJ, Kirnbauer R, Walboomers JM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT (1996) Seroreactivity to HPV16 virus-like particles as a marker for cervical cancer risk in high-risk populations. Int J Cancer 68: 704–709

Nonnenmacher B, Pintos J, Bozzetti MC, Mielzinska-Lohnas I, Lorincz AT, Ikuta N, Schwartsmann G, Villa LL, Schiller JT, Franco E (2003) Epidemiologic correlates of antibody response to human papillomavirus among women at low risk of cervical cancer. Int J STD AIDS 14: 258–265

Onda T, Carter JJ, Koutsky LA, Hughes JP, Lee SK, Kuypers J, Kiviat N, Galloway DA (2003) Characterization of IgA response among women with incident HPV 16 infection. Virology 312: 213–221

Sasagawa T, Yamazaki H, Dong YZ, Satake S, Tateno M, Inoue M (1998) Immunoglobulin-A and -G responses against virus-like particles (VLP) of human papillomavirus type 16 in women with cervical cancer and cervical intra-epithelial lesions. Int J Cancer 75: 529–535

Shah KV, Viscidi RP, Alberg AJ, Helzlsouer KJ, Comstock GW (1997) Antibodies to human papillomavirus 16 and subsequent in situ or invasive cancer of the cervix. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 233–237

Sigstad E, Lie AK, Luostarinen T, Dillner J, Jellum E, Lehtinen M, Thoresen S, Abeler V (2002) A prospective study of the relationship between prediagnostic human papillomavirus seropositivity and HPV DNA in subsequent cervical carcinomas. Br J Cancer 87: 175–180

Stone KM, Karem KL, Sternberg MR, McQuillan GM, Poon AD, Unger ER, Reeves WC (2002) Seroprevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 infection in the United States. J Infect Dis 186: 1396–1402

Touze A, De Sanjose S, Coursaget P, Almirall MR, Palacio V, Meijer CJ, Kornegay J, Bosch FX (2001) Prevalence of anti-human papillomavirus type 16, 18, 31, and 58 virus-like particles in women in the general population and in prostitutes. J Clin Microbiol 39: 4344–4348

van Doornum G, Prins M, Andersson-Ellstrom A, Dillner J (1998) Immunoglobulin A, G, and M responses to L1 and L2 capsids of human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, 18, and 33 L1 after newly acquired infection. Sex Transm Infect 74: 354–360

Wang SS, Schiffman M, Shields TS, Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Bratti MC, Sherman ME, Rodriguez AC, Castle PE, Morales J, Alfaro M, Wright T, Chen S, Clayman B, Burk RD, Viscidi RP (2003) Seroprevalence of human papillomavirus-16, -18, -31, and -45 in a population-based cohort of 10 000 women in Costa Rica. Br J Cancer 89: 1248–1254

Wideroff L, Schiffman M, Haderer P, Armstrong A, Greer CE, Manos MM, Burk RD, Scott DR, Sherman ME, Schiller JT, Hoover RN, Tarone RE, Kirnbauer R (1999) Seroreactivity to human papillomavirus types 16, 18, 31, and 45 virus-like particles in a case-control study of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions. J Infect Dis 180: 1424–1428

Wideroff L, Schiffman MH, Hoover R, Tarone RE, Nonnenmacher B, Hubbert N, Kirnbauer R, Greer CE, Lorincz AT, Manos MM, Glass AG, Scott DR, Sherman ME, Buckland J, Lowy D, Schiller J (1996) Epidemiologic determinants of seroreactivity to human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 virus-like particles in cervical HPV-16 DNA-positive and -negative women. J Infect Dis 174: 937–943

Wideroff L, Schiffman MH, Nonnenmacher B, Hubbert N, Kirnbauer R, Greer CE, Lowy D, Lorincz AT, Manos MM, Glass AG (1995) Evaluation of seroreactivity to human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particles in an incident case-control study of cervical neoplasia. J Infect Dis 172: 1425–1430

Wikstrom A, van Doornum GJ, Quint WG, Schiller JT, Dillner J (1995) Identification of human papillomavirus seroconversions. J Gen Virol 76(Part 3): 529–539

Acknowledgements

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, in accordance with US Department of Health and Human Services guidelines. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the NIH and in Costa Rica. This work was supported by Public Health Service (PHS) contracts N01CP21081 and N01CP31061 between the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, and FUCODOCSA (Costa Rican Foundation for Training in Health Sciences). RD Burk was supported by PHS Grant R01CA78527 from the NCI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Schiffman, M., Herrero, R. et al. Determinants of human papillomavirus 16 serological conversion and persistence in a population-based cohort of 10 000 women in Costa Rica. Br J Cancer 91, 1269–1274 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602088

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602088

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Germline determinants of humoral immune response to HPV-16 protect against oropharyngeal cancer

Nature Communications (2021)

-

Persistence of Trichomonas vaginalis serostatus in men over time

Cancer Causes & Control (2015)

-

Serological prevalence and persistence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection among women in Santiago, Chile

BMC Infectious Diseases (2014)

-

Immunologic treatments for precancerous lesions and uterine cervical cancer

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2014)

-

The association of HPV-16 seropositivity and natural immunity to reinfection: insights from compartmental models

BMC Infectious Diseases (2013)