Abstract

Background:

Risk-stratified management of fever with neutropenia (FN), allows intensive management of high-risk cases and early discharge of low-risk cases. No single, internationally validated, prediction model of the risk of adverse outcomes exists for children and young people. An individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis was undertaken to devise one.

Methods:

The ‘Predicting Infectious Complications in Children with Cancer’ (PICNICC) collaboration was formed by parent representatives, international clinical and methodological experts. Univariable and multivariable analyses, using random effects logistic regression, were undertaken to derive and internally validate a risk-prediction model for outcomes of episodes of FN based on clinical and laboratory data at presentation.

Results:

Data came from 22 different study groups from 15 countries, of 5127 episodes of FN in 3504 patients. There were 1070 episodes in 616 patients from seven studies available for multivariable analysis. Univariable analyses showed associations with microbiologically defined infection (MDI) in many items, including higher temperature, lower white cell counts and acute myeloid leukaemia, but not age. Patients with osteosarcoma/Ewings sarcoma and those with more severe mucositis were associated with a decreased risk of MDI. The predictive model included: malignancy type, temperature, clinically ‘severely unwell’, haemoglobin, white cell count and absolute monocyte count. It showed moderate discrimination (AUROC 0.723, 95% confidence interval 0.711–0.759) and good calibration (calibration slope 0.95). The model was robust to bootstrap and cross-validation sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions:

This new prediction model for risk of MDI appears accurate. It requires prospective studies assessing implementation to assist clinicians and parents/patients in individualised decision making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Children developing cancer in North America and Europe have an 80% chance of cure (Pritchard-Jones et al, 2006; Ward et al, 2014). The cost of this cure, in terms of intensity of therapy and recurrent admissions with toxic effects, is a considerable burden upon children, young people and their families (Chisholm and Dommett, 2006). One such toxicity, fever with neutropenia (FN), also known as ‘febrile neutropenia’ or ‘neutropenic sepsis’, is the clinical dilemma of potentially severe infection in an immunocompromised child or a young person. Its management requires balancing competing risks from overtreatment against undertreatment, and personalising care in FN by accurately differentiating those at higher or lower risk of significant infection, to determine who is eligible for alternative treatment approaches (Lehrnbecher et al, 2012).

Current practice in managing febrile neutropenia in paediatric oncology is variable (Chamberlain et al, 2005; Boragina and Patel, 2007; Stabell et al, 2007; Phillips et al, 2007). Some centres use a risk-stratified reduced intensity approach directed by clinical decision rules, whereas others treat all children with aggressive, in-patient delivered antibiotic therapy.

Systematic reviews (Haeusler et al, 2013a, 2013b; Phillips et al, 2010, 2012a, c) show that many clinical decision rules have been proposed to predict which children will have poor outcomes during episodes of febrile neutropenia. These identified several difficulties including small numbers of patients, analysis techniques which lead to optimistic estimates of predictive power, and lack of validation in different geographies and care systems (Phillips et al, 2012a).

Individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis of data from therapeutic studies has been developed over two decades to improve the precision and reliability of answers to questions of treatment, and provides a means of overcoming many such problems (Stewart and Tierney, 2002; Riley et al, 2010). More recently, the approach has been promoted for developing and validating risk-prediction models from observational data, to improve the quality of answers to important prognostic questions (Altman and Riley, 2005) and matters of diagnostic accuracy (Leeflang et al, 2008), and to establish more robust clinical decision rules. Meta-analysis of IPD from multiple studies allows harmonisation of study data sets, standardisation of end points and analysis methods, as well as greater statistical power to identify more complex statistical relationships (Stewart and Tierney, 2002).

To maximise the value of the information already collected by previous studies and cohorts of children with febrile neutropenia, a global collaboration (The ‘Predicting Infectious Complications in Children with Cancer’: PICNICC) was established to facilitate an IPD meta-analysis that aimed to robustly develop and externally validate a new prediction model for the risk of microbiologically defined infection (MDI) in febrile neutropenic children (Phillips et al, 2012b).

Methods

A detailed protocol for the PICNICC IPD study was developed, registered and published before commencement of the analysis (Phillips et al, 2012b). The primary aim of the IPD analysis was at the onset of an episode of FN to quantify the risk of adverse clinical outcomes according to clinical variables recorded in children and young people aged 0–24 years old undergoing treatment for malignant disease at the onset of an episode of FN, and to develop a new risk-prediction model.

Collaboration development

The PICNICC collaboration comprises international clinical and methodological experts, parent representatives and health-care researchers. Clinical and research experts were identified from trials identified during preliminary systematic reviews of aggregate data (Phillips et al, 2010, 2012c), in response to oral presentations at paediatric oncology conferences, and web-based invitations. Parents/carers were approached via UK parent support organisations. This process led to 22 different study groups from 15 countries joining the PICNICC collaboration. Ethical approval for the study was granted in the UK and individual members were advised to contact their local ethics board to determine the need for approval (Phillips et al, 2013).

Data acquisition

Each collaborative group shared, episode-by-episode, de-identified individual level data from their original studies of new-onset episodes of FN as defined by the original studies. Candidate predictors for inclusion in the risk-prediction model were requested for each study. These were patient-level variables measured on admission, and included: patient age at, and date of, each episode of FN; underlying malignancy type; remission status; chemotherapy type and date of last cycle; type of central venous line; in/out-patient status; maximum temperature; clinical observations including global assessment of illness severity and mucositis; blood count parameters; inflammatory biomarkers; and empirical antibiotics used (Phillips et al, 2012b). A minimum requirement of patient age, malignancy type, one marker of clinical status, antibiotics given, white cell and neutrophil counts and one specified outcome was set. Data were mapped into similar reporting units, for example, mmol into g dl−1, and using predefined structures for cardiovascular, respiratory and mucositis outcomes. The outcome used in this analysis was of MDI. We permitted any definition described in the original study and did not insist on the HIS consensus definition (Immunocompromised Host Society, 1990). The majority of studies used microbiological identification of a pathogen from a sterile site. This outcome was chosen after data collection as it was the most frequently and consistently reported clinically relevant outcome, and was highly correlated with the less frequently reported ‘serious medical complication’ as suggested by the recently published core outcome set (Haeusler et al, 2014).

Statistical methods

IPD from the 22 data sets were cleaned, and the availability of variables and the outcome of interest (MDI) were summarised. Studies were excluded if they did not provide the outcome of interest. Univariable analysis was undertaken to examine the unadjusted effect of each candidate predictor, using random effects logistic regression as described below. The multivariable risk-prediction model was developed using logistic regression, hierarchical of episodes within studies. For multivariable analysis, a complete case analysis was undertaken. Studies were removed if they had not collected information on potentially informative variables that had been deemed important a priori and focused on those predictors with the most complete information (⩽15% missing). These were selected from variables that prior systematic reviews suggested would provide the largest complete data set (see Figure 1). Variables were selected for inclusion in the model by a stepwise selection process—examining improvement in fit with each additional variable added to the model using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), with a P-value of <0.15 and net reclassification improvement (Pencina et al, 2008) used in determining inclusion. Different functional forms for continuous variables were assessed by the use of fractional polynomials before inclusion (Royston and Sauerbrei, 2008). Clustering of patients within studies was accounted for by fitting a random-effect on the intercept. The impact of other potential sources of heterogeneity (e.g., in the effects of particular variables across studies) and other degrees of clustering (e.g., through repeated episodes of the same individual) were evaluated with further random effects. Heuristic shrinkage (Steyerberg, 2009) and the bootstrap procedure (Harrell et al, 1996) using 5000 episodes with replacement were used to adjust for potential overfitting. Performance was internally checked using all-bar-one cross-validation predictive performance (Royston et al, 2004), where the model is repeatedly applied to the derivation data after a single data set has been removed, to assess for systematic miscalibration driven by outlying data sources. Type of antibiotic therapy was incorporated into the model in a sensitivity analysis, as initial discussions considered this may reflect otherwise occult clinical suspicion of serious infection. The calibration of the model was checked by plotting observed against expected values for population deciles, with discrimination calculated using the area under the receiver–operator curve (AUROC), also known as the C-statistic.

Results

Data

IPD information from 5127 episodes of FN in 3504 patients from 22 data sets was provided for analysis (Supplementary Table 1, online).

A wide variety of malignancies were represented in the IPD data sets. Overall there were 52% of patients with acute leukaemias, 27% with solid tumours of childhood, 11% with lymphoma, 7% with brain tumours, 3% with non-malignant conditions treated with chemotherapy (e.g., Langerhans cell histiocytosis) and 2% of children with adult-type solid tumours (e.g., carcinomas of bowel). Only two of the data sets (Genoa, PINE) included patients who had undergone haemopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). The median age of the patients at first episode was 6.8 years, with a range of 50 days to 25 years old, with 14% of patients 16 years or older; 56% of the patients were male.

The IPD collected included a wide range of outcomes and potential predictor variables with marked differences in completeness, interpretation and consistency between data sets. No data set completely reported every item (Figure 1). The most common reason for absent data was that the studies did not collect that variable. The unrecorded data effectively reduced the data set available for multivariable analysis to around 1101 episodes in 742 patients over seven studies. The sparseness of information on biomarkers in comparison with the clinical data meant that these were assessed only in their univariable relationship with MDI and not as part of a multivariable model.

We were unable to obtain data from 30 studies (including 5387 episodes) that had been identified in our previous systematic reviews. Authors of two studies explained that they were unable to participate because the studies were conducted over 20 years ago and data were no longer retrievable; other study groups did not respond or give reasons for not taking part. These unavailable studies did not significantly differ from those included in terms of number of participants (P=0.66), number of episodes (P=0.93), number of events (P=0.67) or geographical region (P=0.25).

Univariable associations with microbiologically defined infection

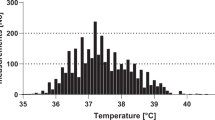

The results of univariable (unadjusted) analyses showed associations between MDI and many variables (Table 1) including the presence of an untunnelled central line, the clinical appearance of being significantly unwell (as defined by the original studies), of documented cardiovascular compromise (shock), a high temperature, raised serum biomarkers, low white cell counts, neutrophil counts or platelets and a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukaemia or relapsed acute leukaemia. There were very few data on patients who had recently received HSCT (3% of all episodes). A surprising univariable association found that patients with more severe mucositis had a smaller chance of MDI than those with less severe mucositis (Table 1). The estimated associations were generally consistent betweyen studies (e.g., Figure 2). Notably, there was no relationship demonstrated between age and risk of MDI.

The biomarkers with sufficient data to examine (<90% missing) were C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin 8. Each biomarker was assessed as the natural logarithm of its reported value to reduce skewness. CRP was not significantly associated with MDI (see Table 1) but IL-8 had a strongly significant association with MDI (OR=1.81, 95% CI 1.48–2.28, τ2=0.00, I2=0%) see Figure 3.

Multivariable model to predict microbiologically defined infection

Because of the pattern of missing data, the final analysis data set used to build the multivariable model contained 1101 episodes of FN from 742 patients in seven studies (Figure 1). Overall 24% (236) of those episodes exhibited a MDI. The analysis examined 15 candidate variables (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2, online), giving an event-to-predictor ratio of 15.7. There was little between-study heterogeneity in the parameter estimates, and no significant difference in the univariable parameter estimates between-studies included and excluded from the multivariable analysis.

Six simple variables were included in the model to predict MDI: type of malignancy; maximum temperature; clinical evaluation of being severely unwell; haemoglobin; white cell count; and absolute monocyte count (AMC).

Logit(p(MDI)ijk)=α+β0k+β1j tumour typeijk+β2 temperatureijk+β3 unwellijk+β4 Hbijk+β5 loge (white cell count)ijk+β6 loge(absolute monocyte count)ijk,

where the subscript i refers to the ith episode, j the jth tumour type, where β1j=0 for acute lymphoblastic laekaemia, and k the kth data set and β0k∼N(0, τ2).

The predictions calibrated well against those expected even when calculated using an average intercept (Figure 4, AUROC 0.723, 95% CI 0.711–0.759).

Calibration of PICNICC predictive model. The calibration plot shows the relationship between ideal (dashed line) and observed (dotted line) predicted values. The rug plot along the bottom demonstrates the distribution of the data points, and the triangles show predictions grouped by decile of the population.

There appeared to be little optimism in the predictive estimates as assessed by bootstrap; the mean difference in AUC values between the bootstrapped estimates applied in their bootstrapped data sets, and the estimates applied in the original data set, being −0.0031 (0.7244 vs 0.7213). The heuristic shrinkage estimate for the model (Steyerberg, 2009) was calculated to be 0.97, in keeping with the very small differences produced by bootstrapping. Forcing the antibiotic used into the model (sensitivity analysis) did not affect its predictive performance. Using nonlinear forms did not improve the model fit. Assessment of how the model performed using all-bar-one cross-validation, also showed no significant systematic differences in calibration (see Supplementary Figure 5). Final parameter estimates can be found in Table 2.

Assessing if a complex model gives meaningful benefits over a simpler one can be seen by comparing the AUROC values apparent in the derivation data. The model using clinical variables only (tumour type, temperature, severely unwell) gave an AUROC of 0.697 (95% CI 0.660–0.734). The addition of the simple full blood count variables (haemoglobin, white count and monocyte count) improved the prediction further to an AUROC of 0.736 (95% CI 0.698–0.774).

Discussion

The final multivariable predictive model had six simple components: tumour type, temperature, clinical description of being ‘severely unwell’ and the results of measurements of haemoglobin concentration, total white cell count and AMC. It showed moderate discrimination (AUROC 0.723, 95% CI 0.711–0.759) and good calibration between predicted and actual estimates of the risk of MDI when assessed across the range of predictive values. The model was robust to bootstrap and cross-validation sensitivity analyses, and built by adding specialist investigations only after considering the simpler pieces of information, ensuring that if extra tests with additional costs are required, they are shown to add predictive power to existing variables.(Altman et al, 1994).

The prediction model developed contained five items which showed consistent relationships across the different study groups (type of malignancy, temperature, unwellness, AMC and total white cell count) and one item (haemoglobin) that was less consistent. The heterogeneity in this item makes it difficult to tell if the inclusion of haemoglobin would be applicable in alternative data sets and subsequently in clinical practice.

The inclusion of clinical impression of the child being significantly unwell as a predictive variable is controversial. The clinical impression of a trained physician is held by some to be of great importance, and by others as unhelpfully subjective and poorly reproducible. Previous investigators have demonstrated objective replicability in paediatric oncology practice (Klaassen et al, 2000), and shown its value in predicting infectious risk in children without an oncological diagnosis(Bruel et al, 2012; Scott et al, 2014) and it is a key element of the widely used (adult) low-risk scoring system of the Multinational Supportive Care in Cancer organisation. (Klastersky et al, 2000) We believe that our analysis supports the use of this variable as providing additional useful information above the objective elements of ‘vital signs’ and full blood count in routine practice.

The value of using both total white count and AMC, rather than one of these items or absolute neutrophil count (ANC), was assessed during the model building. The use of AMC improved AIC (model fit), discrimination and calibration compared with ANC, as did the additional use of total white count. While this appears to contradict the common understanding of how neutrophil counts most importantly indicate the risk of infection—the clinical situation is defined as ‘neutropenic sepsis’, not ‘monocytopenic sepsis’—this analysis confirms data from multiple prior investigations (Rackoff et al, 1996; Klaassen et al, 2000; Baorto et al, 2001; Tezcan et al, 2006). The finding may be explained physiologically by both the neutrophil response to infection and the observed pattern of marrow recovery after chemotherapy, with monocytes preceding neutrophils (Mullen and Buchanan, 1990).

The study was limited in its reliance on study-defined MDI as the key outcome to be predicted, rather than a more comprehensive, patient-important assessment of an adverse outcome of the episode. The lack of a core, agreed definition of ‘significant adverse outcome’ of FN remains a problem to researchers in this area (Haeusler et al, 2013a, 2013b). If one was to be universally agreed, the PICNICC data may be suitable to recalibrate using an alternative outcome.

Relying on the investigators’ original definition of MDI allows the different quality control processes (e.g., numbers of sets of blood cultures taken and volume of blood, or the use of prophylactic antibiotics before presentation) to vary between-studies. This may introduce different degrees of bias between-studies, compared with the ‘true’ MDI status of patients. If this was an important issue, the between-study heterogeneity in predictors would have been marked, and this was not the case in this analysis.

The issue of missing data, almost entirely at the level of study where predictor or outcome variables were ‘not recorded’ rather than ‘missing’, led to a smaller data set being available for the development of the multivariable analyses. Largely, this data set was similar to the total data set when the univariable analyses were compared, except for removing patients who had received HSCT. Although developments in the handling of missing data within studies using simulation have produced guidelines using imputation techniques to maximise the value of the IPD data collected (Burgess et al, 2013; Resche-Rigon et al, 2013; Ahmed et al, 2014), the application of such methods in the situation of unreported data has yet to be explored. Future studies will benefit from adhering to the core items recommended in the recent international position paper on research in this area (Haeusler et al, 2013a, 2013b).

The clinical implementation of the prediction model will require it to be clearly understood by the clinical teams, based on sound data, and easily integrated into practice. The full PICNICC model has complexity (with the series of different predictors for type of malignancy, and the use of log-transformed data) which makes it likely to be unwieldy unless made easily applicable, for example on a spreadsheet (for a basic version see: http://goo.gl/3AOa9R) or smart phone ‘app’, into which the clinicians would enter the data and return a calculated probability of MDI. The model, despite its derivation from data taken from different geographies and eras, requires evaluation in clinical practice from alternative data sets. This could be accomplished by a further global collaboration, building on the existing work, to formally assess the validity in further new data sets, or by individual institutions against locally collected data as a service improvement project. It also needs work undertaking to determine how a prediction of risk can be turned into a decision to employ a particular management strategy, which will require qualitative work with health-care practitioners, families and young people with febrile neutropenia.

We need to collect greater quantities of information on the additional benefit of particular biomarkers and good quality data on their comparative efficacy in initial risk stratification. Moving beyond the initial treatment of FN, and focusing on how we should treat patients with either a defined MDI or those without a clear cause, the patterns of how biomarkers change over time which reflect response to treatment will require evaluation, and also how these patterns may vary both between individuals and within individuals after different elements of their cancer treatment.

This individual patient data meta-analysis represents the largest of its kind; the output of a global collaboration which has shared thousands of items of data and developed a predictive model for MDI which is robust to internal validation techniques. It has demonstrated that such a project is feasible across many different jurisdictions and eras of study, and can provide important verifications and negations of commonly held beliefs.

This prediction model provides a robust method of determining an individual’s chance of MDI during an episode of FN. It should be validated, and used in the context of a clinical trial to enable shared decisions to be made with parents or young people about intensity and location of care for each episode. Such a study should be achievable to prove or disprove the utility of this approach to treatment (Manji et al, 2012) and solidly improve the management of this frequent complication of childhood cancer therapy.

Change history

15 March 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Ahmed I, Debray TP, Moons KG, Riley RD (2014) Developing and validating risk prediction models in an individual participant data meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol 14: 3.

Altman DG, Lausen B, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M (1994) Dangers of using "optimal" cutpoints in the evaluation of prognostic factors. J Natl Cancer Inst 86 (11): 829–835.

Altman DG, Riley RD (2005) Primer: an evidence-based approach to prognostic markers. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 2 (9): 466–472.

Baorto EP, Aquino VM, Mullen CA, Buchanan GR, DeBaun MR (2001) Clinical parameters associated with low bacteremia risk in 1100 pediatric oncology patients with fever and neutropenia. Cancer 92 (4): 909–913.

Boragina M, Patel H (2007) Management of febrile neutropenia in pediatric oncology patients: a Canadian survey. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48 (5): 521–526.

Bruel AVd, Thompson M, Buntinx F, Mant D (2012) Clinicians’ gut feeling about serious infections in children: observational study. BMJ 345: e6144.

Burgess S, White IR, Resche-Rigon M, Wood AM (2013) Combining multiple imputation and meta-analysis with individual participant data. Stat Med 32 (26): 4499–4514.

Chamberlain JD, Smibert E, Skeen J, Alvaro F (2005) Prospective audit of treatment of paediatric febrile neutropenia in Australasia. J Paediatr Child Health 41 (11): 598–603.

Chisholm JC, Dommett R (2006) The evolution towards ambulatory and day-case management of febrile neutropenia. Br J Haematol 135 (1): 3–16.

Haeusler GM, Carlesse F, Phillips RS (2013a) An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the predictive value of serum biomarkers in the assessment of fever during neutropenia in children with cancer. Pediatr Infect Dis J 32 (10): e390–e396.

Haeusler GM, Phillips RS, Lehrnbecher T, Sung L, Ammann RA (2013b) The reporting of outcomes in studies of fever and neutropenia in children with cancer: time for consensus. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (10): 1563–1564.

Haeusler GM, Phillips RS, Lehrnbecher T, Thursky KA, Sung L, Ammann RA (2014) Core outcomes and definitions for pediatric fever and neutropenia research: a consensus statement from an international panel. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (3): 483–489.

Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB (1996) Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 15 (4): 361–387.

Immunocompromised Host Society (1990) The design, analysis, and reporting of clinical trials on the empirical antibiotic management of the neutropenic patient. Report of a consensus panel. J Infect Dis 161 (3): 397–401.

Klaassen RJ, Goodman TR, Pham B, Doyle JJ (2000) "Low-risk" prediction rule for pediatric oncology patients presenting with fever and neutropenia. J Clin Oncol 18 (5): 1012–1019.

Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, Boyer M, Elting L, Feld R, Gallagher J, Herrstedt J, Rapoport B, Rolston K, Talcott J (2000) The multinational association for supportive care in cancer risk index: a multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 18 (16): 3038–3051.

Leeflang MMG, Deeks JJ, Gatsonis C, Bossuyt PMM (2008) Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med 149 (12): 889–897.

Lehrnbecher T, Phillips R, Alexander S, Alvaro F, Carlesse F, Fisher B, Hakim H, Santolaya M, Castagnola E, Davis BL, Dupuis LL, Gibson F, Groll AH, Gaur A, Gupta A, Kebudi R, Petrilli S, Steinbach WJ, Villarroel M, Zaoutis T, Sung L (2012) Guideline for the management of fever and neutropenia in children with cancer and/or undergoing hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 30 (35): 4427–4438.

Manji A, Beyene J, Dupuis LL, Phillips R, Lehrnbecher T, Sung L (2012) Outpatient and oral antibiotic management of low-risk febrile neutropenia are effective in children—a systematic review of prospective trials. Support Care Cancer 20 (6): 1135–1145.

Mullen CA, Buchanan GR (1990) Early hospital discharge of children with cancer treated for fever and neutropenia: identification and management of the low-risk patient. J Clin Oncol 8 (12): 1998–2004.

Pencina MJ, D' Agostino RB, Vasan RS (2008) Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 27 (2): 157–172.

Phillips B, Ranasinghe N, Stewart LA (2013) Ethical and regulatory considerations in the use of individual participant data for studies of disease prediction. Arch Dis Child 98 (7): 567–568.

Phillips B, Selwood K, Lane SM, Skinner R, Gibson F, Chisholm JC (2007) Variation in policies for the management of febrile neutropenia in United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group centres. Arch Dis Child 92 (6): 495–498.

Phillips B, Wade R, Stewart LA, Sutton AJ (2010) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the discriminatory performance of risk prediction rules in febrile neutropaenic episodes in children and young people. Eur J Cancer 46: 2950–2964.

Phillips R, Sutton A, Riley R, Chisholm J, Picton S, Stewart L PICNICC Collaboration (2012a) Predicting infectious complications in neutropenic children and young people with cancer (IPD Protocol). Syst Rev 1 (1): 8.

Phillips RS, Lehrnbecher T, Alexander S, Sung L (2012b) Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the performance of risk prediction rules in children and young people with febrile neutropenia. PLoS One 7 (5): e38300.

Phillips RS, Wade R, Lehrnbecher T, Stewart LA, Sutton AJ (2012c) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the value of initial biomarkers in predicting adverse outcome in febrile neutropenic episodes in children and young people with cancer. BMC Med 10 (1): 6.

Pritchard-Jones K, Kaatsch P, Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller CA, Coebergh JWW (2006) Cancer in children and adolescents in Europe: developments over 20 years and future challenges. Eur J Cancer 42 (13): 2183–2190.

Rackoff WR, Gonin R, Robinson C, Kreissman SG, Breitfeld PB (1996) Predicting the risk of bacteremia in childen with fever and neutropenia. J Clin Oncol 14 (3): 919–924.

Resche-Rigon M, White IR, Bartlett JW, Peters SA, Thompson SG (2013) Multiple imputation for handling systematically missing confounders in meta-analysis of individual participant data. Stat Med 32 (28): 4890–4905.

Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G (2010) Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. Bmj 340: c221.

Royston P, Parmar MK, Sylvester R (2004) Construction and validation of a prognostic model across several studies, with an application in superficial bladder cancer. Stat Med 23 (6): 907–926.

Royston P, Sauerbrei W (2008) Multivariable Model—Building: A Pragmatic Approach to Regression Anaylsis Based on Fractional Polynomials for Modelling Continuous Variables. John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester, England.

Scott H, Donoghue A, Gaieski D, Marchese R, Mistry R (2014) Effectiveness of physical exam signs for early detection of critical illness in pediatric systemic inflammatory response syndrome. BMC Emerg Med 14 (1): 24.

Stabell N, Nordal E, Stensvold E, Gammelsrud KW, Lund B, Taxt A, Buhring F, Greve-Isdahl M, Fornebo HP, Simonsen GS, Klingenberg C (2007) Febrile neutropenia in children with cancer: A retrospective Norwegian multicentre study of clinical and microbiological outcome. Scand J Infect Dis 99999 (1): 1–7.

Stewart LA, Tierney JF (2002) To IPD or not to IPD? Advantages and disadvantages of systematic reviews using individual patient data. Eval Health Prof 25 (1): 76–97.

Steyerberg EW (2009) Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating. Springer: New York, NY, USA.

Tezcan G, Kupesiz A, Ozturk F, Ogunc D, Gultekin M, Yesilipek A, Hazar V (2006) Episodes of fever and neutropenia in children with cancer in a tertiary care medical center in Turkey. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 23 (3): 217–229.

Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A (2014) Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64 (2): 83–103.

Acknowledgements

Mr Neil Ranasinghe (also a co-author), Mrs Sally Amos and Mrs Susan Hay have all specifically helped in their capacity as parents of children who have experienced childhood cancer. A large number of other parents and patients have been highly supportive of the work, for which we are very grateful. This research has been funded as part of a Research Training Fellowship by the Medical Research Council (MRC) UK who funded the work of Dr Phillips. The development of the original MRC fellowship proposal was funded through a grant from Candlelighters, the Yorkshire Children’s Cancer Charity. The funders reviewed the original grant submission but have had no influence on question, design or undertaking the research.

Author Contributions

RSP co-conceived the project, designed the protocol, collated and synthesised the data, undertook the analyses and interpreted the results, and drafted the report. He had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. LAS co-conceived the project, reviewed the results and revised the report. RR supervised the analysis methodology and reviewed and revised the report. LS, EC, RA, RK,WT, TL, JC, HH, MP all contributed to the development of the protocol, sharing and quality assuring the original study data, defining the analyses, interpretation of the results and drafting the paper. GH contributed to the development of the protocol, defining the analyses, interpretation of the results and drafting the paper. NR provided parent/carer views to contributed to the development of the protocol, defining the analyses, interpretation of the results and drafting the paper. The other members of the Collaborative (see below) have shared their clinical and academic expertise, directed the analyses and contributed to data sharing and conceptual developments.

PICNICC Collaboration

The PICNICC Collaboration is formed by those who have contributed data, or for patient/carer partners, significantly developed the project. The members are currently: the Authors, Thomas Kuehne, Felix Niggli & David Nadal (Switzerland), Ricarrdo Haupt (Italy), Sarah Alexander (Canada), Arne Simon (Germany), Karin Meidema (Netherlands), Ajay Gupta (India), Daniel Yeomanson, Alex J Sutton and Rachel Dommett (GB), Pamela Silva & Juan Tordecilla (Chile), Maria Spassova (Bulgaria), Glen Stryjewski (US), Gulsun Tezcan (Turkey), Lidija Kitanovski (Slovenia), Tiene Bauters and Geneviève Laureys (Belgium), J Peter Donnelly (EORTC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Part of these data were presented at the SIOP 46th Congress, Toronto, Canada, September 2014.

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips, R., Sung, L., Amman, R. et al. Predicting microbiologically defined infection in febrile neutropenic episodes in children: global individual participant data multivariable meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 114, 623–630 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.28

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.28

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pro-inflammatory cytokine ratios determine the clinical course of febrile neutropenia in children receiving chemotherapy

Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics (2020)

-

Management of children with fever and neutropenia: results of a survey in 51 pediatric cancer centers in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland

Infection (2020)

-

Pediatric patients at risk for fever in chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in Bern, Switzerland, 1993-2012

Scientific Data (2018)

-

Predictive value of PCT and IL-6 for bacterial infection in children with cancer and febrile neutropenia

Supportive Care in Cancer (2018)

-

Predicting Infectious ComplicatioNs in Children with Cancer: an external validation study

British Journal of Cancer (2017)