Abstract

Background:

Oestrogen receptor-negative (ER−) breast cancer is intrinsically sensitive to chemotherapy. However, tumour response is often incomplete, and relapse occurs with high frequency. The aim of this work was to analyse the molecular characteristics of residual tumours and early response to chemotherapy in patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) of breast cancer.

Methods:

Gene and protein expression profiles were analysed in a panel of ER− breast cancer PDXs before and after chemotherapy treatment. Tumour and stromal interferon-gamma expression was measured in xenografts lysates by human and mouse cytokine arrays, respectively.

Results:

The analysis of residual tumour cells in chemo-responder PDX revealed a strong overexpression of IFN-inducible genes, induced early after AC treatment and associated with increased STAT1 phosphorylation, DNA-damage and apoptosis. No increase in IFN-inducible gene expression was observed in chemo-resistant PDXs upon chemotherapy. Overexpression of IFN-related genes was associated with human IFN-γ secretion by tumour cells.

Conclusions:

Treatment-induced activation of the IFN/STAT1 pathway in tumour cells is associated with chemotherapy response in ER− breast cancer. Further validations in prospective clinical trials will aim to evaluate the usefulness of this signature to assist therapeutic strategies in the clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is currently being used in breast cancer patients with locally advanced disease, and it has increasing applications in patients with initially operable breast cancer but aggressive pathological features (high grade, high proliferation, triple-negative or HER2-positive (HER2+) breast carcinoma). Several trials have shown that achievement of a pathological complete response (pCR) after chemotherapy strongly correlates with favourable long-term outcome (von Minckwitz et al, 2012). Differences in survival between patients with or without a pCR were largest in patients with HER2+/oestrogen receptor-negative (ER−) and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (von Minckwitz et al, 2012).

Despite initial chemosensitivity, patients with TNBC and HER2+/ER− subtypes have worse distant disease-free survival and overall survival than those with the luminal subtypes. In HER2+ breast cancer, adding trastuzumab to chemotherapy significantly increases pCR (Buzdar et al, 2005). For TNBC, however, about 70% of patients do not achieve pCR after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and suffer a dramatically worse outcome, with a higher probability of metastatic relapse and a 3-year OS of only 60–70% (Carey et al, 2007; Liedtke et al, 2008). As a majority of TNBC patients endure the toxicity of cytotoxic chemotherapy (CTX) without benefit, and as valuable time for a potentially more efficient alternative treatment is lost, there is a strong rational for clinical and experimental research to identify predictive markers of response and more efficient therapies.

Several clinical studies reported gene expression changes during NAC (Hannemann et al, 2005; Boidot et al, 2009). Hannemann et al (2005) showed that response of breast cancer to NAC results in gene expression alterations. Gonzalez-Angulo et al (2012) analysed 21 paired tumour samples pre- and post-NAC in basal-like, HER2+ and luminal breast cancer patients. They reported significant changes in several kinase pathways, including PI3K and sonic hedghog, metabolism and immune-related pathways. More recently, Balko et al (2012) profiled formalin-fixed tissues from 49 breast cancers using supervised NanoString gene expression analysis. They found low concentrations of DUSP4 in basal-like breast cancer and demonstrated that its overexpression was associated with CTX-induced apoptosis in cell lines. Korde et al (2010) reported changes in gene expression after one cycle of docetaxel and capecitabine NAC. They identified 71 differentially expressed gene sets, including DNA repair and cell proliferation regulation pathways. By analysing residual samples of tumours partially responsive to anthracyclin/cyclophosphamide (AC) NAC, Koike Folgueira et al (2009) showed that some of them retained their parental molecular signature, whereas others presented significant changes. All studies found biological modifications between pretreatment and posttreatment tumours. However, no common signature or pathway emerged, possibly reflecting patient heterogeneity and/or differences in the neo-adjuvant regimen, the percentage of non-tumour cells (normal, fibrotic and inflammatory tissue), the delay between the biopsy and the last chemotherapy cycle or the technique used for analysis. In addition, no early gene expression changes in post-NAC samples were generally captured in clinical studies.

Transplantable patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) are a valuable preclinical tool to assess drug efficacy, study resistance mechanisms and generate hypotheses that can be tested and translated to the clinic (Hidalgo et al, 2014; Marangoni and Poupon, 2014). The panel of breast cancer PDX models used in this study reproduces the phenotypic and molecular heterogeneity of clinical breast cancer, including response to CTX (Marangoni et al, 2007; Reyal et al, 2012). Several models show very good response to standard CTX that reduces tumours to microscopic residual tumour cell foci, which will eventually fuel local tumour recurrence in vivo (Romanelli et al, 2012). Analysis of these residual tumour foci can assist the investigation of the biological basis of tumour drug response, survival and recurrence (Marangoni et al, 2009; Romanelli et al, 2012). In the present study, we analysed gene expression changes upon CTX administration in a panel of ER− PDX models. We identified induction of genes related to interferon (IFN)/STAT1 pathway as a common feature of chemo-sensitive breast cancers linked to the DNA damage-response. IFN/STAT1 pathway-related gene overexpression was induced early after treatment start and persisted in residual tumour cells, whereas no increased expression was observed in genotoxic treatment-resistant PDXs. This suggest that IFN/STAT1-related gene expression induction could be an early predictive marker of tumour response in ER− breast cancers.

Methods

PDX establishment and in vivo efficacy studies

All patients had previously given their verbal informed consent, at the time of first consultation at the Institut Curie, for experimental research on residual tumour tissue available after histophatological analyses. PDX establishments have been performed after approval of the ethics committee of the Institut Curie.

The care and use of animals used here was strictly applying European and National Regulation for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes in force. This experiment complies with the procedure number 6 approved by the Ethical Committee CEEA-Ile de France Paris (official registration number 59). Swiss nude mice, 10-week-old female, were purchased from Charles River (Les Arbresles, France). Establishment of PDX models from primary breast cancers and in vivo responses to chemotherapies have previously been published (Marangoni et al, 2007). Adriamycin (DOX, Doxorubicin, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Paris, France), cisplatin (CDDP, Teva Pharmaceuticals) and cyclophosphamide (Endoxan, Baxter, Maurepas, France) were administered by intra-peritoneal (i.p.) route at the doses of 2, 6 and 100 mg kg−1, respectively, every 3 weeks. Capecitabine (Xeloda, Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ, USA) was administered per os at the dose of 540 mg kg−1 day−1, q5d × 5 week and Irinotecan (Fresenius Kabi, Sèvres, France) by i.p. route at the dose of 50 mg kg−1 at days 0, 3, 7 and 11. Ruxolitinib (RUX; Novartis, Rueil-Malmaison, France) was given per os at the dose of 30 mg kg−1 3 week−1.

Histological analysis of the inter-scapular fad pad and in situ hybridisation of tumour residues

Histological analysis of residual tumours and in situ hybridisation of a human Alu probe were performed, as previously described (Romanelli et al, 2012). Tumours with at least 40% of tumour content, as determined by histology, were included in the study.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) characterisation of xenografted tumours

Xenografted tumours were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin embedded and haematoxylin–eosin (H&E) stained to differentiate the human tumour components from the murine stroma. Tumour tissues were analysed by IHC for expression of the following biomarkers: P-STAT1Tyr701 (1/1000; Cell Signaling Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France), P-γ-H2AXSer139 (1/1000; Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). P-STAT1Tyr701-positive tumour foci were counted in untreated and RUX-treated tumour sections; mean±s.d., n=5 per group. Nuclear staining was considered positive for P-γ-H2AX expression. For each tumour, the percentage of P-γ-H2AX staining was evaluated in seven different areas.

Gene expression studies

Before gene expression analysis, tumour samples were microdissected using laser capture microdissection technology, according to the PALM protocol (outsourced to ZEISS, Munich, Germany). RNA was extracted from microdissected areas using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). This approach allowed isolating foci of human tumour cells from the murine stroma. Gene expression analysis was performed with Affymetrix Exon 1.0 ST microarrays. Hybridisation, data normalisation and statistical analysis were outsourced to GenoSplice Technology (Paris, France). Additional statistical analyses were performed using BRB-ArrayTools (developed by Richard Simon and BRB-ArrayTools Development Team at NCI). Microarray data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (GSE58990).

Real-time PCR amplification

Theoretical and practical aspects of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) have been previously described (Bieche et al, 2001; Reyal et al, 2012). For normalisation, averaged expression of at least two genes among the human RPL13, TBP, HPRT or GAPDH housekeeping genes was used in each experiment. Detailed protocols for cDNA synthesis, PCR amplifications and gene normalisation were described elsewhere (Tozlu et al, 2006; Romanelli et al, 2012). Data were normalised to housekeeping gene expression and untreated tumour samples, mean±s.d., n=3 per group. All human primers were tested for human specificity. The list of primers used for SybrGreen and Taqman-mediated assays is available on request.

Western blotting

Protein were extracted in non-denaturing lysis buffer and quantified with the microBCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Lysates were resolved on 4–12% TGX gels (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), transferred into nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) and immunoblotted overnight at 4 °C or 1 h at room temperature with the following antibodies: P-STAT1Tyr701, CASP-3 (1/750–1000; Cell Signaling Ozyme), Total STAT1 (1/1000; Santa Cruz antibodies, Nanterre, France), P-STAT1Ser727, P-γH2AXSer139 (1/1000; Merck Millipore), OAS1, IFI44, LCN2, or Actin, as an internal control loading (1/1000; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, directed against the species of primary antibody (Pierce), during 1 h at room temperature before chemoluminescence reading. Western blotting was performed in triplicate, and data show a representative finding of these triplicate analyses. To determine species specificity, antibodies against P-STAT1 and STAT1 were also tested in IHC in the HBCx-10 xenograft: P-STAT1 staining appeared restricted to tumour cells, while STAT1 antibody stained both cancer (human) and fibroblast (murine) cells (data not shown).

Cytokine array analyses

Tumour cytokine levels were measured using mouse and human cytokine array (panel A and B), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Three hundred micrograms of total protein lysates were extracted and pooled from tumours of three mice similarly treated. Horseradish peroxidase substrate (R&D Systems) was used to detect protein expression. Arrays were scanned using Fx7 camera system (Fusion Molecular Imaging Fx7) and optical density measurement was obtained with the Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Data were obtained in duplicate, mean±s.d., n=3 mice per group.

Ex vivo assays for caspase 3/7 activity

Tumour protein extracts were prepared in lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (PMSF, aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstain A, Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France) and incubated during 1 h at 4 °C. Activity was measured on synthetic substrate Ac-DEVD-AFC for caspase-3/7 (AnaSpec, San Jose, CA, USA). Enzymatic reactions were allowed to proceed for 30 min at room temperature. Fluorescence intensity was measured at different time points on a PerkinElmer LS 50B spectrofluorometer (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Norwalk, CT, USA) (δEx/δEm=380/500 nm). Specificity of the fluorometric signal was confirmed by adding specific caspase inhibitor to the reaction mixture (CASP-3 inhibitor, z-DEVD-fmk). Caspase 3/7 activity was measured in picomoles of AFC released per minute and milligrams of protein using a standard curve of free AFC.

Results

Gene expression profiling of postchemotherapy residual tumours identifies upregulation of IFN-inducible genes

To characterise molecular changes occurring in residual tumour cells after chemotherapy, we used three TNBC PDX models previously described (Marangoni et al, 2007; de Plater et al, 2010): HBCx-6, HBCx-8, and HBCx-17. In these models, treatment by AC results in tumour regression, followed by tumour regrowth (Figure 1A).

Upregulation of IFN -inducible genes and STAT1 phosphorylation in residual tumour foci after AC treatment. (A) In vivo response of HBCx-17 to AC (2/100 mg kg−1) (mean tumour volume±s.d.) n=11 per group. (B) H&E analysis and in situ hybridisation of Alu probes of one residual tumour foci after chemotherapy response (× 25). (C) Type I and II interferon distribution by ISG Database. (D) qRT–PCR analysis of STAT1 and eight other IFN-inducible genes in untreated samples, residual and regrowing tumours. HBCx-6, HBCx-8 HBCx-10 and HBCx-17 PDX were treated with AC, mean±s.d., n=5 per group. Comparative analysis of all samples from the four experiments in different experimental conditions (Rel: relapse; Rem: remission; Untr: untreated); fold-change refers to mean intensity value ratio between the two experimental condition indicated. P-value was calculated by t-test except for results indicated with *=t-test with Welch’s correction or **=Mann–Whitney test. (E) Western blotting of P-STAT1Tyr701/Ser727, STAT1, IF44, LCN2 and OAS1 in three PDX models responding to AC treatment. Tumours were analysed at the indicated phases: untreated (U), residual (N=nodule) and relapse tumour (R=Relapse).

PDX models were treated by one cycle of AC, and tumours were micro-dissected at three different time points: before chemotherapy, during response (residual stage), and at tumour recurrence. At the residual disease stage, cancer cells could be identified in the inter-scapular fat pad by in situ hybridisation with Alu probes that detect human genomic sequences. An example is shown in Figure 1B: two tissue sections of a residual tumour excised from the fad pad during the remission stage have been stained with H&E (top) and hybridised in situ with Alu probes (Alu, bottom). Two distinct nodules containing human cancer cells are stained in blue within the mouse stroma.

In order to identify genes commonly deregulated, gene expression analysis was performed by comparing gene expression profile of residual tumours and untreated control tumours from HBCx-6, HBCx-8 and HBCx-17 PDXs. Two hundred and seventy-four genes were differentially expressed at P-value <0.05 (Supplementary Table S1). Among the most significantly upregulated genes, many were IFN-inducible genes (Table 1). The IFN pathway was activated in post-AC residual tumours of the three models (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2). A comparison between the list of 274 genes and the IFN-regulated genes database (http://www.interferome.org) (Rusinova et al, 2013) showed that 83 genes corresponded to genes involved in both type I (a and b) and type II (g) IFN signalling pathways, while only 32 and 25 genes were specifically involved in type I and II pathways, respectively (Figure 1C).

To confirm IFN pathway activation, a selected number of IFN-inducible genes (IFIT1, IFIT3, IFI6, IF44, MX1, STAT1, IFI27, IFNB1, ISG15) were analysed by qPCR with human-specific primers in untreated and residual tumours samples of these three PDXs, plus HBCx-10, an additional TNBC PDX model highly responsive to AC (Figure 1C). Comparative gene expression analysis of pooled untreated, residual and regrowing tumours from the four experiments confirmed significant upregulation of IFN-inducible genes in residual tumours. We also evaluated whether activation of the IFN-related genes is a transient or constitutive event by measuring the expression of the signature in tumours at relapse. As shown in Figure 1C, IFN-related gene expression intensity in regrowing tumours returns to the levels measured before treatment, indicating that the ovrerexpression observed is a transient event.

To determine whether this activation occurs also in HER2+ breast cancer treated with AC, we measured the expression level of the IFN signature in the HBCx-5 PDX, established from a lymph node HER2+ metastasis (Marangoni et al, 2007). As for the TNBC models, we found the IFN genes upregulated after AC treatment at the residual disease stage (Supplementary Figure S1).

As transcription of IFN-inducible genes is dependent on STAT1 phosphorylation (Levy and Darnell, 2002), we analysed the expression of P-STAT1 and total STAT1 levels by western blotting in PDX treated with AC-based chemotherapy. Consistent with the mRNA data, total STAT1 expression was constantly increased in residual tumour foci compared with untreated and regrowing tumours (Figure 1D). P-STAT1 isoforms (P-STAT1Tyr701 and P-STAT1Ser727) were also strongly increased in all residues tested. Expression of STAT1-target proteins: IFI44, LCN2, and OAS1 was also increased in residual tumour cells in two out of three models, as compared with untreated or regrowing tumours (Figure 1D). Taken together, these results reveal the existence of an IFN signature in residual cancer cells after treatment by AC, associated with STAT1 phosphorylation.

Upregulation of IFN-inducible genes is not restricted to AC chemotherapy

To investigate whether this upregulation was specifically linked to AC chemotherapy, the same analysis was performed in the HBCx-33 TNBC model, responder to cisplatin and capecitabine chemotherapies (Figure 2A). We found IFN-inducible genes upregulated in residual tumours after both treatments, indicating that IFN signature upregulation was not specific to AC chemotherapy (Figure 2B). In addition, the analysis of gene expression in individual tumours showed that upregulation of IFN-inducible genes was no longer detectable 30 days after cisplatin treatment (xenograft #5, Figure 2C). Overall, these results indicate that activation of IFN-inducible genes is not chemotherapy dependent and does not persist over time.

Response to cisplatin and capecitabine treatment and expression analysis of the IFN -inducible genes in the HBCx-33 xenograft. (A) In vivo response to cisplatin (6 mg kg−1) and capecitabine (540 mg kg−1 day−1) in HBCx-33 xenograft. (B) Expression analysis of IFN-inducible genes after capecitabine and cisplatin treatments. Mean±s.d., n=6. (C) Individual growth curves after cisplatin treatment in the ‘residual tumour group’ of HBCx33 xenograft and gene expression analysis of the IFN-inducible genes.

Activation of the IFN pathway is an early event following AC chemotherapy in AC-responder tumours in vivo

To further analyse the relationship between activation of IFN-inducible genes and response to chemotherapy, the expression of 21 genes (BST2, CLDN1, DDX60, IFI44, IFI44L, IFI6, IFIT1, IFIT3, IFITM1, IRF9, LAMP3, MX1, OAS1, OAS2, PARP9, PARP12, SAMD9, STAT1, STAT2, UBE2L6, ZNFX1) selected from the IFN/STAT1 signature was measured 3 (D3) and 7 days (D7) following AC treatment in 9 TNBC that respond to AC and 5 TNBC and 1 HER2-positive non-responder PDXs by qPCR (Figure 3). Expression of the majority of the IFN-inducible genes was found increased at D3 and D7 posttreatment only in AC-responder tumours, whereas no overexpression was observed in resistant tumour models (Figure 3A). Comparative analysis of the IFN-related signature expression level at this two time points in sensitive and resistant models showed that overexpression at D7 was higher for the majority of the genes of the signature in the majority of PDXs analysed, as accounted by a stronger P-value (Supplementary Table S3). We asked whether the lack of IFN/STAT1 pathway activation in AC-resistant tumours was due to an intrinsic tumour cell inability to activate the STAT1 pathway following administration of a drug that induces DNA damage. To answer this question, we analysed the expression of IFN-related genes in a HER2+ PDX (HBCx-13), a model that is resistant to AC but that responds well to irinotecan (Figure 3B). Interestingly, we found that IFN-inducible genes were strongly upregulated 7–14 days after irinotecan treatment but not after AC treatment. This result suggests that IFN/STAT1 activation is tightly associated with drug efficacy and not with intrinsic tumour ability or inability to activate the pathway.

Analysis of IFN/STAT1 pathway activity in chemo-responder and chemo-resistant PDX at early stage after chemotherapy. (A) mRNA expression of a 21-gene IFN/STAT1 signature analysed by qPCR at days 0, 3 and 7 post-AC treatment in 9 responders and 5 resistant models. Each curve represents the expression of one gene. (B) In vivo response to AC and irinotecan in the HER2+ HBCx13 model and analysis of IFN-inducible genes (BST2, CLDN1, DDX60, IFI44, IFI44L, IFI6, IFIT1, IFIT3, IFITM1, IRF9, MX1, OAS1, OAS2, PARP12, PARP9, SAMD9, STAT1, STAT2, UBE2L6, ZNFX1) at D7 and D14.

Overall, these results show that upregulation of IFN-inducible genes is associated with response to chemotherapy in vivo.

Assessment of caspase-3/7 activity and P- γ H2AX expression in AC-treated tumours

A number of studies previously reported an implication of STAT1 in the DNA-damage response (DDR) (Townsend et al, 2005; Brzostek-Racine et al, 2011). We therefore assessed the effects of AC administration on markers of DNA damage and apoptosis by measuring phoshporylated-γH2AX (P-γH2AX) and caspase-3/7 activity in both chemo-sensitive and chemo-resistant tumours. Cleavage of pro-CASP3 (32 kDa) into 17 and 12 kDa subunits revealed CASP3 activity in responder tumours at D7 post-AC, while no caspase-3 activity was observed in resistant tumours (Figure 4A and B). The percentage of tumour cells with P-γH2AX foci increased to up to 80–90% in responder tumours at D3-D7 post-AC treatment, while it reached only 40% in non-responder tumours (Figure 4C and D). These results indicate that tumour response and activation of IFN/STAT1 pathway are associated to massive DNA damage induction and apoptosis.

Analysis of Caspase-3/7 activity and P- γ H2AX in TNBC PDX models treated with AC. (A) Western blotting analysis of CASP-3 and P-γH2AX1Ser139 in 3 AC-responder and 2 AC-non-responder models at 3 and 7 days after AC treatment. (B) Caspase-3/7 activity in 5 AC-responder and 3 AC-non-responder tumours at D3 and D7 following AC treatment. (C) IHC analysis of P-γH2AXSer139 in 3 responder and 3 non-responder tumours at D3 and D7 after AC treatment (× 200). (D) Fractions of P-γH2AX-positive nuclei quantified in responder (HBCx-6, HBCx-10 and HBCx-17) and non-responder tumours (HBCx-2, HBCx-7 and HBCx-12B) at D0, D3 and D7 after AC treatment. Mean±s.d., n=3. Statistical significance is measured by Student’s t-test. *P⩽0.05; **P⩽0.01; ***P⩽0.001; ****P⩽0.0001.

Early induction of INF-related genes is associated with STAT1 phosphorylation and IFN- γ secretion in tumour cells

To determine whether early induction of IFN-related genes was associated with STAT1 activation, we measured STAT1 phosphorylation at days 3 and 7 after AC treatment in four resistant and four responder PDXs. Time-course western blotting analysis of STAT1 protein expression after AC treatment showed that the amounts of total STAT1, P-STAT1Tyr701 and P-STAT1Ser727 isoforms were simultaneously increased between 3 and/or 7 days after treatment in responder tumours (Figure 5A), while no increase was observed in AC-resistant tumours.

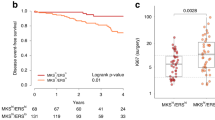

Activation of JAK/STAT1 pathway and expression of IFN- γ in the early response to AC. (A) Western blotting analysis of total STAT1 or P-STAT1Tyr701/Ser727 in four responders and four resistant models at D0, D3 and D7 post-AC treatment. (B) Human and murine soluble IFN-γ expression determined by cytokine array in HBCx-10 tumours at D3, D7 and D14 after AC and during residual and regrowing phases. (C) Effect of RUX alone on HBCx-10 tumour growth. Mean RTV±s.d., n=10. (D) P-STAT1Tyr701 foci detected by IHC in one untreated xenograft and the number of P-STAT1Tyr701-positive tumour cells in untreated and RUX-treated tumour samples. *P⩽0.05 (Student's t-test). (E) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of mice treated with chemotherapy alone and with chemotherapy and RUX (P<0.0001, log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test). (F) Expression of IFN-inducible genes by qPCR in untreated, AC, RUX alone or RUX/AC groups at 8 days (D8) posttreatment.

To determine whether STAT1 phosphorylation could be related to IFN secretion by an autocrine mechanism or by the surrounding environment, the expression of tumour (human) and stromal (mouse) IFN-γ was analysed at different time points after chemotherapy (D3, D7, D14, residual tumour stage and regrowth) in tumour protein lysates from HBCx-10 model, using human- and mouse-specific cytokine arrays. Results showed a small increase in murine IFN-γ detectable at D14 after AC and in residual tumour samples, while the level of human IFN-γ was dramatically increased at D3 and D7 (Figure 5B), indicating that chemotherapy stimulates the secretion of IFN-γ by the tumour cells at an early stage after treatment. As IFN-α and -β were not present in the cytokine array, we measured their mRNA expression by RT–PCR in the HBCx-10 and HBCx-33 PDX. IFN-α was not detected, while IFNβ expression was increased in residual tumours of the HBCx-10 tumour after AC treatment (P=0.045) and of the HBCx-33 PDX after capecitabine treatment (P=0.015) (Supplementary Figure S2).

Inhibition of JAK activity by RUX does not change response to chemotherapy

To evaluate whether STAT1 phosphorylation is mediated by the IFN/JAK pathway during early response to chemotherapy, and if this effect is causally involved with tumour response, HBCx10 tumour model was treated with the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor RUX (Mesa et al, 2012) prior to AC administration. RUX treatment was started at D1 and AC treatment was given at D8 (concomitant schedule). In addition, to inhibit JAK/STAT pathway during residual tumour stage, RUX treatment was started when tumour had regressed 3 weeks after AC administration (sequential schedule). RUX administered as single agent did not affect tumour growth but induced a significant reduction in the number of P-STAT1Tyr701-positive tumour foci (Figure 5C and D). To analyse the effect of RUX on the expression of IFN-related genes upon treatment, qPCR analysis was performed in four groups of mice: untreated, AC treated, RUX treated, and AC+RUX treated. Tumours treated with AC alone or in combination with RUX showed the same response profile, as shown by survival curves (Figure 5E). Despite a decreased expression of IFN-related genes in the RUX-treated groups, the increase of IFN-related gene expression in the AC+RUX-treated tumours, compared with RUX-treated group, was identical to the increase measured in the AC-treated group compared with the untreated tumours. (Figure 5F). Also, RUX treatment did not prevent nor delay tumour regrowth when administered in the sequential schedule. These results indicate that tumour response is strongly associated with increased expression of IFN-related genes and that it does not depend on the basal expression level of IFN-related genes. In addition, they suggest that induction of IFN-related gene expression by chemotherapy could be independent of the canonical JAK/STAT pathway.

Discussion

To explore the molecular basis of drug response and residual cancer cell persistence after chemotherapy, we used a panel of TNBC and HER2+ breast cancer PDX models. The analysis of tumour gene expression before and after chemotherapy treatment showed a consistent upregulation in residual tumours of a group of IFN-inducible genes, associated with increased STAT1 and P-STAT1 protein levels. More than 50% of upregulated genes corresponded to genes involved in both α/β and γ IFN signalling, as suggested by the comparison between the list of genes and the IFN-stimulated genes database (Rusinova et al, 2013).

Enrichment of JAK/STAT-related genes in residual tumours surviving chemotherapy has been reported in a transgenic murine breast cancer model (Franci et al, 2013). Franci et al (2013) performed a microarray analysis of MMTV-PyMT residual tumours after TAC chemotherapy in vivo (docetaxel, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide) and found enrichment of the JAK/STAT pathway, Notch pathway and epigenetic regulators. Our findings that IFN/STAT pathway activation following AC administration is an early and transient event, which turned off after 3 weeks and returned to pretreatment levels in regrowing tumours (Figure 1C), suggests that this upregulation is a direct consequence of chemotherapy administration rather than an enrichment of cancer cells with an intrinsic pretreatment signature. In support of this hypothesis, upregulation of IFN-inducible genes was no longer detectable in tumours analysed at later time points during the regression phase.

Activation of the IFN/STAT pathway was restricted to PDX models that responded to chemotherapy. One explanation is that IFN/STAT activation is linked to the DDR induced by chemotherapy. This is in line with the findings that both caspase activity and P-γH2AX, an early marker of DNA damage, also increased significantly in AC-responder tumours. Previous studies reported a connection between STAT1 and the DDR, such as the role of STAT1 in activation of the ATM-Chk2 checkpoint pathway following gamma ray-irradiation (Townsend et al, 2005), and the activation of the IFN/STAT1 pathway in human cells treated with genotoxic agents (Brzostek-Racine et al, 2011). In addition, a recent work showed that murine cell lines exhibited overexpression of IFN-related genes when BRCA2 was knocked down (Xu et al, 2014).

The absence of induced STAT1 activation observed in AC-resistant tumour may be due either to failure of the drugs to induce sufficient DNA damage or to a lack of functional STAT1 downstream signalling during the DDR. We consider the second possibility as unlikely as STAT1 activation and tumour regression could be induced by irinotecan in the AC-resistant HBCx-13 model. Tumour resistance to cyclophosphamide and alkylating agents has been previously attributed to detoxifying mechanisms upstream of DNA damage, such as elevated aldehyde dehydrogenase, increased glutathione levels and/or glutathione-S-transferase activity (Andersson et al, 1994; Richardson and Siemann, 1995; Miyake et al, 2012), and temporal factors related to the efficiency of DNA repair were also suggested (Andersson et al, 1994). Further work will be needed to identify the mechanisms mediating resistance to AC in non-responder TNBCs.

We considered the hypothesis that activation of the IFN/STAT1 pathway could be associated with the presence of cytokines secreted by stromal tumour-infiltrating cells in relation to drug-induced cell death and/or inflammation. Indeed, intratumoural infiltration by lymphocytes and IFN response in primary tumour predicts the efficacy of NAC in breast cancer patients (Andre et al, 2013). In addition, the fact that STAT1 activation has been previously observed in vitro upon exposure of tumour cells to genotoxic insult suggests that it can occur in the absence of stroma or IFN-secreting immune cells (Townsend et al, 2005; Brzostek-Racine et al, 2011; Hussner et al, 2012). As one of the activators of the IFN canonical pathway is IFN-γ, which binds to IFN-γ receptors to activate the JAK/STAT cascade (Platanias, 2005), we measured the level of both human and mouse cytokines in the HBCx-10 xenograft. The finding that expression of human but not murine IFN-γ was increased 3 days after chemotherapy administration suggests that, at least in this xenograft model, early IFN/STAT pathway activation may be related to an autocrine mechanism, where the tumour cells secrete IFN-γ. Although human IFN-α and -β were not included in the cytokine array, the RT–PCR analysis showed an increase of IFN-β mRNA level in residual tumours after chemotherapy treatment, suggesting possible involvement of type I IFN signalling in these tumours. This hypothesis is further supported by the study recently published by Sistigu et al (2014), showing that the therapeutic activity of anthracyclines relies on IFN I signalling in neoplastic cells. However, the HBCx-10-relapsing tumours contained high level of human IFN-γ while the IFN signature was absent. This could signify that relapsing tumours could be insensitive to IFN-γ-induced signature or that other cytokines, such as IFN-α and -β, might contribute to the induction of IFN-related genes.

Further studies will clarify whether IFNs secreted by tumour cells exerts a rather paracrine activity on the surrounding stromal component.

Upon exposure to the JAK inhibitor RUX, P-STAT1 levels and the baseline expression level of IFN-inducible genes was clearly reduced in the tumour without impacting growth rate. Also, when administered at residual tumour stage to tumours that had previously received AC treatment, RUX did not prevent nor delayed tumour regrowth, indicating that the JAK/STAT1 signalling is not essential to sustain tumour proliferation in this model. Exposure of untreated or RUX-treated HBCx-10 PDX to AC induced both the same response profile and early increase of IFN/STAT-related gene expression in the two groups, suggesting that the baseline expression level of IFN-inducible genes is not relevant in determining tumour response. The observation that the increase of IFN-related gene expression in the AC+RUX-treated tumours was not completely abolished could be due to an incomplete inhibition of JAK activity. Alternatively, activation of IFN signature genes could be independent of JAK1/JAK2 signalling. Various reports show that the IFN/STAT1 pathway can also be upregulated by JAK-independent signals, such as PDGF signalling, ligand-activated EGFR or hypoxia (Pedersen et al, 2005; Zhang et al, 2005; Jechlinger et al, 2006). Thus it is possible that in vivo activation of the IFN/STAT1 pathway could result from combined non-canonical factors and cytokines through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms.

Another hypothesis could be that both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated STAT1 (U-STAT1) are involved in STAT1 target gene activation. Indeed, U-STAT1 is itself able to activate and prolong transcription of IFN-inducible genes, including IFI27, IFI44, OAS1 and BST2, (Cheon and Stark, 2009), and STAT1 can function as a transcription factor in the absence of tyrosine phosphorylation (Kumar et al, 1997). Although the role of U-STAT1 is still partially understood, there is increased evidence that it can drive gene expression by mechanisms distinct from those used by phosphorylated STAT1 dimers (Yang and Stark, 2008).

A two-step model of STAT1 pathway activation has been described where an initial IFN-dependent and P-STAT1-mediated activation of STAT1 target genes, which is short-lived because it induces cell death, is followed by persistent activation of a restricted target gene repertoire by U-STAT1, which is tolerated by cells while affording antiviral and DNA damage resistance functions (Cheon and Stark, 2009; Cheon et al, 2013). This model is also supported by other groups who reported that ionising radiation induce IFN-inducible genes activation, including STAT1, IFIT1, OAS1 and MX1 in several types cancers (glioma, breast, prostate, colon and head and neck cancers) (Khodarev et al, 2007; Tsai et al, 2007). STAT1 activation is therefore neither restricted to breast cancer nor to chemotherapy-induced genotoxicity. Both P-STAT1 and U-STAT1 could have a role in activating gene transcription of IFN-related genes after chemotherapy in vivo. In the clinical setting, patients receive several cycles of genotoxic treatment, whereas in our in vivo experiments mice were subjected to only one dose of chemotherapy. It would be interesting to evaluate whether repeated tumour exposure to genotoxic drugs can select for tumour cells that constitutively express IFN-related genes. Given the possibly dual role of this pathway in mediating either tumour suppression or drug resistance, further experiments should aim at dissecting the mechanisms by which the STAT1 pathway may have an active role in initial AC-induced tumour cell death on one hand and in the survival of residual tumour cells on the other hand.

A clinical study reported JAK/STAT pathway activation 3 weeks after doxorubicin administration in breast cancer patients (Lee et al, 2009). Although it was not clearly indicated whether this activation was restricted to tumours responding to doxorubicin, this work indicates that such an event also occurs in patients. Finally, activation of STAT1 and IFN-inducible genes after chemotherapy has been also reported in retinoblastoma tumours from two patients (Nalini et al, 2013), suggesting that this activation would be not restricted to breast cancers.

In summary, we present for the first time evidence that induction of IFN-related genes is an early event that discriminates chemo-sensitive from chemo-resistant tumours. This signature is a good surrogate of induced DNA damage and cell death by chemotherapy. Further validations in prospective clinical trials will be necessary to evaluate the possible usefulness of this signature in assisting therapeutic strategies in the neo-adjuvant settings. Particularly, early detection of inefficient administration of a given genotoxic compound could form the basis of a decision to switch patient’s treatment to alternative therapies.

Change history

19 January 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Andersson BS, Mroue M, Britten RA, Murray D (1994) The role of DNA damage in the resistance of human chronic myeloid leukemia cells to cyclophosphamide analogues. Cancer Res 54 (20): 5394–5400.

Andre F, Dieci MV, Dubsky P, Sotiriou C, Curigliano G, Denkert C, Loi S (2013) Molecular pathways: involvement of immune pathways in the therapeutic response and outcome in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 19 (1): 28–33.

Balko JM, Cook RS, Vaught DB, Kuba MG, Miller TW, Bhola NE, Sanders ME, Granja-Ingram NM, Smith JJ, Meszoely IM, Salter J, Dowsett M, Stemke-Hale K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Mills GB, Pinto JA, Gomez HL, Arteaga CL (2012) Profiling of residual breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies DUSP4 deficiency as a mechanism of drug resistance. Nat Med 18 (7): 1052–1059.

Bieche I, Parfait B, Le Doussal V, Olivi M, Rio MC, Lidereau R, Vidaud M (2001) Identification of CGA as a novel estrogen receptor-responsive gene in breast cancer: an outstanding candidate marker to predict the response to endocrine therapy. Cancer Res 61 (4): 1652–1658.

Boidot R, Vegran F, Soubeyrand MS, Fumoleau P, Coudert B, Lizard-Nacol S (2009) Variations in gene expression and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast carcinoma. Cancer Invest 27 (5): 521–528.

Brzostek-Racine S, Gordon C, Van Scoy S, Reich NC (2011) The DNA damage response induces IFN. J Immunol 187 (10): 5336–5345.

Buzdar AU, Ibrahim NK, Francis D, Booser DJ, Thomas ES, Theriault RL, Pusztai L, Green MC, Arun BK, Giordano SH, Cristofanilli M, Frye DK, Smith TL, Hunt KK, Singletary SE, Sahin AA, Ewer MS, Buchholz TA, Berry D, Hortobagyi GN (2005) Significantly higher pathologic complete remission rate after neoadjuvant therapy with trastuzumab, paclitaxel, and epirubicin chemotherapy: results of a randomized trial in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive operable breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23 (16): 3676–3685.

Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, Gatti L, Moore DT, Collichio F, Ollila DW, Sartor CI, Graham ML, Perou CM (2007) The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res 13 (8): 2329–2334.

Cheon H, Holvey-Bates EG, Schoggins JW, Forster S, Hertzog P, Imanaka N, Rice CM, Jackson MW, Junk DJ, Stark GR (2013) IFNbeta-dependent increases in STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 mediate resistance to viruses and DNA damage. EMBO J 32 (20): 2751–2763.

Cheon H, Stark GR (2009) Unphosphorylated STAT1 prolongs the expression of interferon-induced immune regulatory genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106 (23): 9373–9378.

de Plater L, Lauge A, Guyader C, Poupon MF, Assayag F, de Cremoux P, Vincent-Salomon A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Sigal-Zafrani B, Fontaine JJ, Brough R, Lord CJ, Ashworth A, Cottu P, Decaudin D, Marangoni E (2010) Establishment and characterisation of a new breast cancer xenograft obtained from a woman carrying a germline BRCA2 mutation. Br J Cancer 103 (8): 1192–1200.

Franci C, Zhou J, Jiang Z, Modrusan Z, Good Z, Jackson E, Kouros-Mehr H (2013) Biomarkers of residual disease, disseminated tumor cells, and metastases in the MMTV-PyMT breast cancer model. PLoS One 8 (3): e58183.

Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Iwamoto T, Liu S, Chen H, Do KA, Hortobagyi GN, Mills GB, Meric-Bernstam F, Symmans WF, Pusztai L (2012) Gene expression, molecular class changes, and pathway analysis after neoadjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 18 (4): 1109–1119.

Hannemann J, Oosterkamp HM, Bosch CA, Velds A, Wessels LF, Loo C, Rutgers EJ, Rodenhuis S, van de Vijver MJ (2005) Changes in gene expression associated with response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23 (15): 3331–3342.

Hidalgo M, Amant F, Biankin AV, Budinska E, Byrne AT, Caldas C, Clarke RB, de Jong S, Jonkers J, Maelandsmo GM, Roman-Roman S, Seoane J, Trusolino L, Villanueva A (2014) Patient-derived xenograft models: an emerging platform for translational cancer research. Cancer Discov 4 (9): 998–1013.

Hussner J, Ameling S, Hammer E, Herzog S, Steil L, Schwebe M, Niessen J, Schroeder HW, Kroemer HK, Ritter CA, Volker U, Bien S (2012) Regulation of interferon-inducible proteins by doxorubicin via interferon gamma-Janus tyrosine kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling in tumor cells. Mol Pharmacol 81 (5): 679–688.

Jechlinger M, Sommer A, Moriggl R, Seither P, Kraut N, Capodiecci P, Donovan M, Cordon-Cardo C, Beug H, Grunert S (2006) Autocrine PDGFR signaling promotes mammary cancer metastasis. J Clin Invest 116 (6): 1561–1570.

Khodarev NN, Minn AJ, Efimova EV, Darga TE, Labay E, Beckett M, Mauceri HJ, Roizman B, Weichselbaum RR (2007) Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 regulates both cytotoxic and prosurvival functions in tumor cells. Cancer Res 67 (19): 9214–9220.

Koike Folgueira MA, Brentani H, Carraro DM, De Camargo Barros Filho M, Hirata Katayama ML, Santana de Abreu AP, Mantovani Barbosa E, De Oliveira CT, Patrao DF, Mota LD, Netto MM, Caldeira JR, Brentani MM (2009) Gene expression profile of residual breast cancer after doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Rep 22 (4): 805–813.

Korde LA, Lusa L, McShane L, Lebowitz PF, Lukes L, Camphausen K, Parker JS, Swain SM, Hunter K, Zujewski JA (2010) Gene expression pathway analysis to predict response to neoadjuvant docetaxel and capecitabine for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 119 (3): 685–699.

Kumar A, Commane M, Flickinger TW, Horvath CM, Stark GR (1997) Defective TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis in STAT1-null cells due to low constitutive levels of caspases. Science 278 (5343): 1630–1632.

Lee SC, Xu X, Lim YW, Iau P, Sukri N, Lim SE, Yap HL, Yeo WL, Tan P, Tan SH, McLeod H, Goh BC (2009) Chemotherapy-induced tumor gene expression changes in human breast cancers. Pharmacogenet Genomics 19 (3): 181–192.

Levy DE, Darnell JE (2002) Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3 (9): 651–662.

Liedtke C, Mazouni C, Hess KR, Andre F, Tordai A, Mejia JA, Symmans WF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hennessy B, Green M, Cristofanilli M, Hortobagyi GN, Pusztai L (2008) Response to neoadjuvant therapy and long-term survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 26 (8): 1275–1281.

Marangoni E, Lecomte N, Durand L, de Pinieux G, Decaudin D, Chomienne C, Smadja-Joffe F, Poupon MF (2009) CD44 targeting reduces tumour growth and prevents post-chemotherapy relapse of human breast cancers xenografts. Br J Cancer 100 (6): 918–922.

Marangoni E, Poupon MF (2014) Patient-derived tumour xenografts as models for breast cancer drug development. Curr Opin Oncol 26 (6): 556–561.

Marangoni E, Vincent-Salomon A, Auger N, Degeorges A, Assayag F, de Cremoux P, de Plater L, Guyader C, De Pinieux G, Judde JG, Rebucci M, Tran-Perennou C, Sastre-Garau X, Sigal-Zafrani B, Delattre O, Dieras V, Poupon MF (2007) A new model of patient tumor-derived breast cancer xenografts for preclinical assays. Clin Cancer Res 13 (13): 3989–3998.

Mesa RA, Yasothan U, Kirkpatrick P (2012) Ruxolitinib. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11 (2): 103–104.

Miyake T, Nakayama T, Naoi Y, Yamamoto N, Otani Y, Kim SJ, Shimazu K, Shimomura A, Maruyama N, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S (2012) GSTP1 expression predicts poor pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in ER-negative breast cancer. Cancer Sci 103 (5): 913–920.

Nalini V, Segu R, Deepa PR, Khetan V, Vasudevan M, Krishnakumar S (2013) Molecular insights on post-chemotherapy retinoblastoma by microarray gene expression analysis. Bioinform Biol Insights 7: 289–306.

Pedersen MW, Pedersen N, Damstrup L, Villingshoj M, Sonder SU, Rieneck K, Bovin LF, Spang-Thomsen M, Poulsen HS (2005) Analysis of the epidermal growth factor receptor specific transcriptome: effect of receptor expression level and an activating mutation. J Cell Biochem 96 (2): 412–427.

Platanias LC (2005) Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 5 (5): 375–386.

Reyal F, Guyader C, Decraene C, Lucchesi C, Auger N, Assayag F, De Plater L, Gentien D, Poupon MF, Cottu P, De Cremoux P, Gestraud P, Vincent-Salomon A, Fontaine JJ, Roman-Roman S, Delattre O, Decaudin D, Marangoni E (2012) Molecular profiling of patient-derived breast cancer xenografts. Breast Cancer Res 14 (1): R11.

Richardson ME, Siemann DW (1995) DNA damage in cyclophosphamide-resistant tumor cells: the role of glutathione. Cancer Res 55 (8): 1691–1695.

Romanelli A, Clark A, Assayag F, Chateau-Joubert S, Poupon MF, Servely JL, Fontaine JJ, Liu X, Spooner E, Goodstal S, de Cremoux P, Bieche I, Decaudin D, Marangoni E (2012) Inhibiting aurora kinases reduces tumor growth and suppresses tumor recurrence after chemotherapy in patient-derived triple-negative breast cancer xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther 11 (12): 2693–2703.

Rusinova I, Forster S, Yu S, Kannan A, Masse M, Cumming H, Chapman R, Hertzog PJ (2013) Interferome v2.0: an updated database of annotated interferon-regulated genes. Nucleic Acids Res 41 (Database issue): D1040–D1046.

Sistigu A, Yamazaki T, Vacchelli E, Chaba K, Enot DP, Adam J, Vitale I, Goubar A, Baracco EE, Remedios C, Fend L, Hannani D, Aymeric L, Ma Y, Niso-Santano M, Kepp O, Schultze JL, Tuting T, Belardelli F, Bracci L, La Sorsa V, Ziccheddu G, Sestili P, Urbani F, Delorenzi M, Lacroix-Triki M, Quidville V, Conforti R, Spano JP, Pusztai L, Poirier-Colame V, Delaloge S, Penault-Llorca F, Ladoire S, Arnould L, Cyrta J, Dessoliers MC, Eggermont A, Bianchi ME, Pittet M, Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Preville X, Uze G, Schreiber RD, Chow MT, Smyth MJ, Proietti E, Andre F, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L (2014) Cancer cell-autonomous contribution of type I interferon signaling to the efficacy of chemotherapy. Nat Med 20 (11): 1301–1309.

Townsend PA, Cragg MS, Davidson SM, McCormick J, Barry S, Lawrence KM, Knight RA, Hubank M, Chen PL, Latchman DS, Stephanou A (2005) STAT-1 facilitates the ATM activated checkpoint pathway following DNA damage. J Cell Sci 118 (Pt 8): 1629–1639.

Tozlu S, Girault I, Vacher S, Vendrell J, Andrieu C, Spyratos F, Cohen P, Lidereau R, Bieche I (2006) Identification of novel genes that co-cluster with estrogen receptor alpha in breast tumor biopsy specimens, using a large-scale real-time reverse transcription-PCR approach. Endocr Relat Cancer 13 (4): 1109–1120.

Tsai MH, Cook JA, Chandramouli GV, DeGraff W, Yan H, Zhao S, Coleman CN, Mitchell JB, Chuang EY (2007) Gene expression profiling of breast, prostate, and glioma cells following single versus fractionated doses of radiation. Cancer Res 67 (8): 3845–3852.

von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, Eidtmann H, Fasching PA, Gerber B, Eiermann W, Hilfrich J, Huober J, Jackisch C, Kaufmann M, Konecny GE, Denkert C, Nekljudova V, Mehta K, Loibl S (2012) Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 30 (15): 1796–1804.

Xu H, Xian J, Vire E, McKinney S, Wei V, Wong J, Tong R, Kouzarides T, Caldas C, Aparicio S (2014) Up-regulation of the interferon-related genes in BRCA2 knockout epithelial cells. J Pathol 234 (3): 386–397.

Yang J, Stark GR (2008) Roles of unphosphorylated STATs in signaling. Cell Res 18 (4): 443–451.

Zhang X, Shan P, Alam J, Fu XY, Lee PJ (2005) Carbon monoxide differentially modulates STAT1 and STAT3 and inhibits apoptosis via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and p38 kinase-dependent STAT3 pathway during anoxia-reoxygenation injury. J Biol Chem 280 (10): 8714–8721.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pierre de la Grange, Justine Biet, Sophie Banis and Enora LeVen for technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Legrier, ME., Bièche, I., Gaston, J. et al. Activation of IFN/STAT1 signalling predicts response to chemotherapy in oestrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Br J Cancer 114, 177–187 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.398

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.398

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Polymer lipid hybrid nanoparticles encapsulated with Emodin combined with DOX reverse multidrug resistance of breast cancer via IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway

Cancer Nanotechnology (2024)

-

Rewiring of the 3D genome during acquisition of carboplatin resistance in a triple-negative breast cancer patient-derived xenograft

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

STING protects breast cancer cells from intrinsic and genotoxic-induced DNA instability via a non-canonical, cell-autonomous pathway

Oncogene (2021)

-

A highly annotated database of genes associated with platinum resistance in cancer

Oncogene (2021)

-

STING-dependent paracriny shapes apoptotic priming of breast tumors in response to anti-mitotic treatment

Nature Communications (2020)