Abstract

Background:

The mechanisms by which stress hormones impact triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) etiology and treatment are unclear. We have previously shown that stress hormones, cortisol, and catecholamines induce rapid DNA damage and impact DNA repair in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. This study investigates whether stress hormones increase DNA damage in breast cancer cells and if this impacts drug efficacy.

Methods:

We first screened a panel of 39 breast cancer cell lines for expression of adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptors and examined if stress hormones induce DNA damage and alter cell cycle regulation in vitro. A TNBC xenograft model was used to assess the impact of restraint stress on tumour growth and chemosensitivity to paclitaxel.

Results:

We found that stress hormones induced DNA damage, phosphorylation of ATR, which was accompanied by an up-regulation of the G1 cell kinase inhibitor p21 and a cell cycle halt of TNBCs in the G1 phase. p21 knockdown abrogated G1 arrest by stress hormones. We also demonstrated that stress significantly decreased efficacy of paclitaxel.

Conclusion:

We describe a novel mechanism through which stress hormones can induce drug resistance to paclitaxel, which may have profound implications for treating drug resistance in patients with TNBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for ∼15–20% of all subtypes of breast cancer and are characterised by a lack of expression of estrogen/progesterone and ERBB2 (Ossovskaya et al, 2011; Metzger-Filho et al, 2012). Patients with TNBC are treated with standard chemotherapy treatments and these patients exhibit shorter disease-free survival and a high rate of relapse (Dent et al, 2007; Dent et al, 2009; Brouckaert et al, 2012; Chu et al, 2012). Furthermore, these patients with TNBC can develop resistance to standard therapies. Although many risk factors have been associated with the progression of breast cancer (Nelson et al, 2012), the effects of psychological stress are only now starting to be recognised. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 165 longitudinal studies concluded that psychosocial factors are associated with higher incidence, poorer survival, and increased mortality from breast cancer (Chida et al, 2008). Furthermore, exposure to stress increases tumour growth and metastasis in animal models of breast cancer (Hermes et al, 2009; Sloan et al, 2010; Madden et al, 2013). However, little is known about the molecular pathways by which stress-induced hormones may influence development and progression of breast cancer tissues that possess stress hormone receptors (Vazquez et al, 2006b), although there are several possibilities (Flint and Bovbjerg, 2012). The β-adrenergic receptor is arguably the most well-studied receptor in the context of catecholamine-induced tumour progression (Thaker et al, 2006; Sloan et al, 2010; Sood et al, 2010). However, the role of catecholamines in drug resistance has not been well established. Glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone, have been reported to have a role in drug resistance in breast cancer by enhancing anti-apoptosis mechanisms and transcriptional regulation of genes regulating cell-survival mechanisms (Wu et al, 2004; Petrella et al, 2006). In addition, patients with ER-negative tumours expressing high levels of GR had a worse prognosis (Pan et al, 2011). Further work by the same group showed that pre-treatment with the GR receptor blocker, mifepristone, actually enhanced the efficacy of paclitaxel through increases in anti-apoptotic mechanisms in TNBC (Volden and Conzen, 2013; Skor et al, 2013a, 2013b).

We previously showed that stress hormones (cortisol, (Cort), norepinephrine (NE), and epinephrine (E)) at physiological concentrations rapidly induce DNA damage, and interfere with the DNA-damage repair process in pre-cancerous cells leading to cell transformation and tumorigenicity (Flint et al, 2007; Flint et al, 2012). Consistent with our initial findings, although not in cancer cells, two recent reports suggest molecular mechanisms by which catecholamines can trigger DNA damage and suppress p53 levels, respectively, thus synergistically leading to the accumulation of elevated levels of DNA damage (Hara et al, 2011, 2012). We have shown that stress hormones not only induce rapid DNA damage, but also impact DNA repair by altering DNA repair proteins such as Chk1 and Chk2 kinases (Flint et al, 2007). We have previously shown in vitro using MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells that stress hormones can negatively affect the efficacy of a microtubule disrupting agent, paclitaxel, in co-culture through Cdk-1 (Flint et al, 2009). However, the direct impact of stress hormones on cancer cells to render them drug resistant is not yet known. In this manuscript, we test our hypothesis that stress hormones can induce drug resistance in TNBC models by confirming the presence and function of stress hormone receptors, assessing DNA damage and cell cycle arrest by stress hormones and test the effects of restraint stress on the efficacy of paclitaxel in a mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Breast cancer cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and obtained from the Integrative Cancer Biology Program (ICBP) 45 breast cancer cell line kit (ICBP45) of the National Cancer Institute. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium and Hams nutrient mixture (F-12) and HCC1187 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 and F-12 1 : 1 each with 4 mM L-glutamine and charcoal-stripped bovine calf serum (10%) and MCF-7 Cells were cultured in DMEM and charcoal-stripped bovine calf serum (10%) in a 37 °C incubator at 5% CO2. All cells were plated in a six-well plate and experiments performed in triplicate unless indicated otherwise.

Hormone and chemotherapy studies

Cortisol, norepinephrine, RU486, propranolol, and paclitaxel (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) were prepared as described previously (Flint et al, 2009). Breast cancer cells were incubated with paclitaxel (10−7 M) and either cortisol (10−6 M) or NE (10−7 M) individually, or in combination. These concentrations mimic the physiological levels of circulating cortisol and NE generated during acute stress reported by other researchers (Rupprecht et al, 1997; Rupprecht et al, 1999). To determine hormone specificity, cells were co-treated with the GC receptor antagonist, RU-486 (10−6 M) or beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist, propranolol (10−6 M) for 30 min before stress hormones.

QPCR method for adrenergic receptor screening for breast cancer cell lines

Total RNA extraction was performed using GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ, USA) illustra RNAspin Mini RNA Isolation Kit protocol. Total RNA quantified by Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer. Total RNA (1 μg) was used for first strand synthesis reaction using Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix according to manufacturer protocol. SYBR Green PCR Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used and the cDNA was analysed on Bio-Rad C1000 Thermal Cycler CFX96 Real-Time System, and CFX Software. Data were analysed with the Standard Curve Method using beta-actin as an internal reference gene. Primers: Integrated DNA Technologies custom designed intron- spanning codes for mRNA: eight adrenergic receptors, glucocorticoid receptor, and beta-actin (Table 1).

cAMP assay

Intracellular cAMP content was measured using an Enzyme Immune Assay kit (Cayman-Cyclic AMP EIA kit; Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with indicated concentrations of NE or 1 μ M forskolin for various times. After treatment, the cells were incubated with 0.1 M HCl before incubation with cAMP tracers overnight, developed with Ellman’s reagent and analysed at 405 nM using a Luminometer (Promega Glomax Multidection system, Sunnydale, CA, USA).

Dual luciferase assay

Cells were plated in a 24-well plate for 24 h before transfection with an expression plasmid coding for a GR VS fusion protein, a reporter plasmid containing the luciferase gene linked to a synthetic promoter containing TAT3 binding sites and a Renilla expression plasmid (Fugene 6, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Cells were stimulated with NE in media containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS for 16 h. Both luciferase and Renilla activity were quantified with the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) using a luminometer (Wallac Victor3, PerkinElmer Biosciences, Waltham, MA, USA). Luciferase activity was normalised to the Renilla activity within each sample.

Comet assay

TNBC cells were embedded in LMAgarose in preparation for the Comet assay a single-cell gel electrophoresis assay (Collins, 2004). A total of 1 × 105 cells were mixed in low melting point agarose in PBS and pipetted onto slides pre-coated with 1% agarose and the comet was performed exactly as described previously (Flint et al, 2007).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were treated with paclitaxel and stress hormones as described above. Briefly, cells were trypsinised, washed with PBS and fixed with 100% ethanol at 4 °C for 1 h. Cell suspensions were then incubated with 50 ng μl−1 of RNase A for 15 min at 37 °C followed by 50 ng μl−1 of propidium iodide for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cells were analysed on a LSR II flow cytometer using the FACSDiva data analysis software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Cell cycle distributions were generated using BD FACS Diva software version 6.1.1.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were plated into six-well plates on coverslips before exposure to stress hormones for 4 h. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 15 min and washed with PBS. Cells were permeabilised with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min, washed with PBS, and blocked with PBS, 0.1% Tween-20, and 1% BSA for 30 min. Cells were incubated with an anti-phospho-H2AX primary antibody (Cell Signaling, Beverley, CA, USA) for 2 h, followed by an anti-Rabbit Alexa 546 (Molecular Probes by Life Technology, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 1 h. Cells were washed with PBS and counterstained with 0.1 μg ml−1 Hoechst stain and mounted to glass slides with Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes, Life Technology). One hundred cells were scored at random for each sample using an epi-fluorescence microscope described earlier. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Gene silencing with siRNAs

For gene silencing, RNAi siRNA against p21 was purchased from Cell Signaling. Control siRNA (Cell Signaling) was used as a negative control. Transient transfection of siRNA was carried out using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two × 105 cells were plated into six-well plates 24 h before transfection. Cells were incubated with the final concentration (20 nM) of siRNA for control and p21 with Lipofectamine for 48 h followed by 24 h exposure of stress hormones. Cells were subsequently processed for either flow cytometry or western blot (see below).

Western blot

Following treatments with stress hormones, cells were trypsinised, washed with PBS, and lysed with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM NaVO4, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1% Triton X-100. Lysates were cleared at 13 000 g for 10 min. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad). A total 30 μg of protein was eluted in reducing SDS–PAGE sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and resolved by SDS–PAGE, then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were blocked with 5% BSA in 0.1% TBS-T followed by probing with the following primary antibodies p21; Cell Signaling, Phospho-ATR (Ser428), ATR Phospho-Chk1 (Ser345) (133D3) Rabbit mAb, (DNA Damage Antibody Sampler Kit #9947), ATR, Cell Signaling (2390) Rabbit mAb, Chk-1 goat mAB (Abcam AB2845, Cambridge, MA, USA), Cell Signaling and phospho histone γH2AX; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA), and then incubated with corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Mouse anti-actin (Millipore) primary antibody served as a control. Protein quantification was conducted by densitometric analysis using Image J software.

Cell viability

Cell viability was assessed using a standard trypan blue assay (Sigma). Cells were treated with stress hormones as described above. Cells were treated with 1 μ M of paclitaxel or vincristine in the presence or absence of stress hormones.

Xenografts

Female nude mice (nu/nu; 6 weeks old; 20±2 g) were used. The animal room was maintained on a 12-h light/12-h dark diurnal cycle. All animals were given food and water ad libitum. All mouse protocols were approved by IACUC at the University of Pittsburgh. Mice were injected with 5 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells per 0.2 ml) into the left inguinal mammary fat pad. The tumours took 6–8 weeks to become established, with tumour volumes ∼80–100 mm3. Tumour volumes were calculated twice weekly using a digital caliper and the formula, vol (mm3)=LxW2/2; length (L, mm) and width (W, mm). Mice bearing xenografts were randomised 3 days before treatment (day −3). At day 0, groups of mice received either a dose of paclitaxel (IP; dose of 10 mg kg−1 per week for 3 weeks) or vehicle (Cremophor EL-ethanol-saline 1 : 1 : 8 (v/v/v) as 0.01 ml g−1 body weight on day 0, 7, and 14. For the stress model, (described in (Flint et al, 2000, 2011) groups of mice were placed individually in adequately ventilated tubes. Restraint stress was applied to test groups (chemotherapy and vehicle-treated groups) three times a week (1000–1200 hours) for 3 weeks. Mice were removed from the study if tumours exceeded 2000 mm3.

Statistical analyses

Measurements from cell culture assays were compared between groups against control or against the predetermined reference group using analysis of variance. Tumour volume measurements were log-transformed to satisfy linearity assumptions and a mixed model was fit to account for correlation of repeated measures within subject. Growth rates, represented as slopes, were compared across and within groups. Within-group means and standard deviations are reported and all tests are two-sided at a nominal 0.05 significance level.

Results

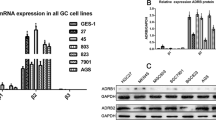

Stress hormone receptors are dynamically expressed in breast cancer cell lines

We observed that different breast cancer cell lines with diverse pathological and molecular features exhibited heterogeneity in expression levels of stress hormone receptors GR and each ADR (Figure 1A). Further analyses showed that GR expression is significantly higher in TNBC cell lines (P=0.01, Figure 1B). ADRB2 expression (one of the key catecholamine receptors in cancer) was also found to trend higher in a subset of TNBC (Supplementary Figure S1A). We used MDA-MB-231 cells; a widely used model of TNBC with previously reported stress hormone receptors (Vazquez et al, 2006a) and HCC1187 cells; a TNBC model expressing higher levels of ADR and GR, for further analyses. Both cells lines are basal and possess p53 mutations. We showed that GR was constitutively expressed in MDA-MB-231 cells and was increased by the synthetic GC, dexamethasone P=0.001 (Figure 1C). NE increases cAMP production through α- or β-ADR and we found that NE increased cAMP levels in MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1D). To fully evaluate that a mechanism through which stress hormones could induce drug resistance, we initially tested whether NE can stimulate the GR (Schmidt et al, 2001) and we determined that although GR was constitutively expressed in both TNBC cells and increased by dexamethasone, NE had no significant effect on GR expression in MDA-MB-231 cells but decreased GR expression in the presence of DEX in HCC1187 cells (Supplementary Figure S1B and C).

GR and ADR stress hormone receptors are dynamically expressed and activated in a panel of breast cancer cell lines. (A) RNA was isolated from a panel of breast cancer cell lines and glucocorticoid and adrenergic receptors were measured by real-time PCR. Expression level is relative across each breast cancer cell line for each transcriptional target. Stress hormone receptors were dynamically expressed among the cell lines (B) Significant GR expression was detected in TNBC cell lines comparative to cell lines expressing ER+, PR+ Her2+. (C) GR activation in MDA-MB-231 cells by luciferase. GR was expressed constitutively and significantly increased by dexamethasone. (D) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with different doses of NE for 15 min and cAMP levels were analysed by a competitive EIA. Incubation of MDA-MB-231 cells at indicated increasing concentrations of NE (0.01–1 mM) illustrated a positive correlation to cAMP levels. *P>0.05 and **P>0.01.

Stress hormones induce DNA damage and cause G1 arrest

In MDA-MB-231 cells, treatment with Cort and NE induced a significant two-fold increase in DNA damage (P=0.01 for each hormone; Figure 2A). Similarly, in HCC1187 cells, which express relatively high levels of GR and ADR, we observed a three-fold increase in DNA damage by Cort and NE (P<0.001 for each hormone) (Figure 2B). When exposed to the hormones in combination, DNA damage was greater than with treatment of Cort or NE alone in MDA-MB-231 cells (P=0.0001 compared with control and P=0.03 compared with Cort or NE only) suggesting an additive effect and HCC1187 (P=0.0001 compared with control). An additive effect in HCC1187 cells was not observed although this may be because the damage observed was at the highest detection limit for the assay. Hydrogen peroxide-treated cells served as a positive control. To determine whether cells lines expressing wild-type p53 are also prone to DNA damage by SH, we conducted the same experiment in MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines and we found that similar to TNBC, we observed a significant increase in DNA damage P<0.001 for each hormone (Supplementary Figure S2)

Stress hormones induce DNA damage in TNBC cells. (A) MDA-MB-231 and (B) HCC1187 cells were incubated with Cort or NE in the presence or absence of receptor anatagonists (RU-486 and propranolol) for 24 h and assessed for DNA damage by the comet assay (n=3 for MDA-MB-231 and n=2 for HC1187). Both Cort and NE induced significant DNA damage in both cells with greater degree of damage observed in HCC1187 cells. (C) MDA-MB-231 cells were also incubated as indicated and stained for γH2AX–P by immunofluorescence, original magnification × 200. (D) Quantifications are shown for MDA-MB-231 and HCC1187 and (E) 100 cells were counted and scored positive if they contained five or more foci. Outcomes were compared using analysis of variance followed by planned paired comparisons. *P>0.05, **P>0.01 and ***P>0.001.

In MDA-MB-231 cells, we found that Cort and NE increased γH2AX phosphorylation when compared with unstimulated controls at 24 h. Lower concentrations of NE increased γH2AX-P with the peak response at 10−6 M Cort and 10−7 M NE, whereas a high concentration (10−5 M) partially decreased γH2AX-P (Supplementary Figure S3). Further, NE and Cort (P<0.001 for both) induced prominent γH2AX foci in MDA-MB-231 cells and increased γH2AX by NE (P=0.02) and Cort (P=0.06) in HCC1187 cells (Figure 2C and quantification Figure 2D and E). Treatment with 10 μ M cisplatin for 24 h served as a positive control and induced a marked increase in the number of cells expressing γH2AX foci (Figure 2C). We also observed a significantly diminished presence of nuclei in cells treated with receptor antagonists, RU-486 and propranolol before exposure to corresponding stress hormones Cort and NE.

FACS analyses showed that a higher percentage of MDA-MB-231 cells were found in the G1 phase following treatment with stress hormones (P=0.04, Figure 3A). A higher fraction of cells treated with paclitaxel alone were found in G2/M phase (P=0.003). Combined treatment of paclitaxel and stress hormones resulted in a significant proportion of cells remaining in G1, compared to paclitaxel alone (P=0.003 in MDA-MB-231), presumably preventing paclitaxel from targeting the cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Interestingly, we did not observe a striking G1 arrest when receptor antagonist were added for each hormone. Alternatively, we used BT474 cells, which have low expression of SH receptors (Figure 1A) and although others have shown GR expression in BT474 cells, they did not exhibit G1 cell cycle arrest in response to DEX (Sumikawa et al, 2008); further, we found that NE failed to induce cAMP in cells and stress hormones did not result in significant cell cycle arrest in G1 phase of the cell cycle (Figure 3B and C), suggesting that stress hormone effects on the cell cycle are receptor mediated; however, further work dissecting these the role of the glucocorticoid and adrenergic receptors in G1 cell cycle halt is warranted.

Stress hormones arrest cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle in TNBC cell lines expressing high but not low levels of stress hormone receptors. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with Cort or NE for 24 h and stained with PI and analysed by FACs analysis (n=2). There was a higher percentage of cells in the G1 phase (grey bar) of the cell cycle in cells treated with stress hormones alone and in the presence of paclitaxel. (B) BT474 cell lines (low stress hormone expressers) were incubated with NE for 15 min and cAMP levels were analysed by a competitive EIA. NE failed to increase cAMP and (C) stained with PI and analysed by FACs analysis (n=2). Outcomes were compared using analysis of variance followed by planned paired comparisons. *P>0.05, **P>0.01 and ***P>0.001.

Stress hormones induce ATR, Chk1 phosphorylation and p21 expression through GR and ADR

Similar to γH2AX P levels, we observed a dose response for phosphorylated ATR and p21 with the peak response at 10−6 M Cort and 10−7 M NE, while the high concentration (10−5 M) partially decreased phosphorylated levels of ATR and p21 (Supplementary Figure S3). MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with stress hormones for 2 and 6 h and western blotting for phospho-ATR, phospho-Chk1, and p21 was performed (Figure 4A, quantifications B–D). At 2 h, we found that NE and Cort individually and more robustly in combination increased ATR serine 425 phosphorylation and total protein levels were slightly decreased at 2 h. Although this did not achieve statistical significance, we found that stress hormones increased Chk1 serine 345 phosphorylation (a major target of ATR) in two out of three experiments, which was inhibited when cells were pretreated with propranolol and RU-486 (mifepristone). Chk1 total protein expression was increased in all treatments at 2 and 6 h. At 6 h, ATR phosphorylation was not sustained, and total ATR protein levels remained unchanged, demonstrating that the DNA damage response is working effectively. We initially determined that paclitaxel, NE, and Cort increased p21 at 2, 6, and 24 h with the most robust increases at 2–6 h (Supplementary Figure S4). We further confirmed this data at 2 and 6 h and showed that Cort and NE showed a trend towards an increase in p21, and these levels were reduced in cells pre-treated with RU-486 and propranolol, respectively. The most striking finding was that treatment with a combination of Cort and NE significantly increased p21 at both time points (Figure 4A).

Stress hormones induce ATR, Chk1, and P21 in TNBC cells. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with Cort or NE in the presence or absence of receptor antagonists, RU-486 and propranolol for 2 and 6 h and cell lysates were prepared and resolved by SDS-PAGE and analysed for phospho ATR (ser 428) and phospho Chk1 (ser 345) by western blotting (n=4 and n=3). Total protein levels of ATR and Chk1 were included as controls (n=2). Density of western blot bands was analysed using Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Densities of phospho ATR and Chk-1 phosphorylation in stress hormone-treated proteins bands were normalised to density of actin (B–D). Theoretical molecular masses in kilodaltons are shown. Stress hormones increased the expression of ATR, CHK1, and p21 proteins in MDA-MB-231 cells. *P>0.05 and **P>0.005.

Similar to MDA-MB-231 cells, in HCC1187 cells, we observed an increase in ATR with NE and Cort at 2 h, which was reversed in cells pretreated with the receptor antagonist, propranolol (Supplementary Figure S5). We observed increases in phospho-Chk1 with Cort but not with NE at 2 h and p21 was increased in cells treated with NE and Cort alone at 2 h and Cort at 6 h (Supplementary Figure S5). Because the hormones were shown to arrest cells in the G1 phase, this would serve as a mechanism to inhibit paclitaxel efficacy, which targets cells in the G2/M phase. To confirm the role of p21, we used two approaches; p21 knockdown in our MDA-MB-231 cells and MDA-MB-436 cells, which have been reported to possess little or no p21 (Promkan et al, 2009). Using the first approach, we found that SH induced G1 arrest in cells treated with control siRNA and significantly prevented in cells treated with p21 siRNA (Figure 5A and western blot showing knockdown Figure 5B). In MDA-MB-436 cells, we found that treatment with stress hormones had no effect on the efficacy of paclitaxel as evidenced by a lack of significant changes in G1 cell cycle arrest and cell viability (Figure 5C and D). Furthermore, Phospho-ATR and Chk1 were not increased by stress hormones compared with unstimulated cells (Figure 5E).

P21 knockdown prevents G1 arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB 231 cells were treated with stress hormones for 24 h after knockdown of p21 by siRNA. (A) Flow cytometry showing that there was a higher percentage of cells in the G1 phase (grey bar) of the cell cycle in cells treated with control siRNA and stress hormones. There was no significant difference in cells treated with p21 siRNA and stress hormones compared with unstim (n=3). (B) Western blot showing p21 knockdown in MDA-MB-231 cells. Stress hormones had no effect on cell cycle regulation (C) and cell viability (D) in the p21 null MDA-MB 436 cell lines. Stress hormones do not induce phospho ATR or Chk-1 (E). Outcomes were compared using analysis of variance followed by planned paired comparisons. **P>0.01.

Stress hormones prevent microtubule targeting agent-induced cell cytotoxicity

MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with paclitaxel (Pac; a microtubule stabilising agent) or Vincristine (Vin; inhibitor of microtubule assembly) in the presence or absence of Cort NE and E for 24 h (Figure 6A and B). At 24 h, Pac killed 50% of the cells (P=0.003 compared with unstimulated) and that this mortality was decreased by treatment with Cort or NE individually and significantly decreased in combination (P=0.03) at 24 h. Similarly at 24 h, Vin killed 50% of the cells and this mortality was significantly prevented, compared with unstimulated, by co-culture with Cort (P=0.03), cat (P=0.04) individually or highly significantly in combination (P=0.01).

Repetitive restraint stress decreases the efficacy of paclitaxel. MDA-MB-231 cells (n=3) were incubated with (A) 1 μ M Pac or (B) 1 μ M Vin in the presence and absence of drug and stress hormones or stress hormones alone for 24 h and assessed for viability using trypan blue dye exclusion. TNBC cells treated with stress hormones had greater viability than cells treated with paclitaxel or vincristine alone. Tumour-bearing mice were randomly assigned to the following treatment groups (vehicle no stress (NS) n=8, vehicle stress (S) n=7, paclitaxel no stress (NS) n=4, and paclitaxel stress n=8). Growth rates were compared on a log scale using a linear model for repeated measures. Growth rates±s.d. shown. (C) Restraint stress resulted in increased serum corticosterone levels. (D) Stress at day 0, 7, and 14 significantly reduced the efficacy of paclitaxel as demonstrated by an increase in tumour volume and altered growth curve in stressed mice. In the absence of paclitaxel, stress significantly decreased tumour volume. *P>0.05 and **P>0.01.

Restraint stress decreases the efficacy of paclitaxel

To begin to translate our findings in vivo, we designed an experiment to establish whether psychological stress could decrease the efficacy of paclitaxel. The stress system functions as a positive bi-directional feedback loop; activation of one component of the system stimulates other components at multiple levels (reviewed in Thaker et al (2013)) we decided to use the restraint stress model and we first wanted to ensure that our model could induce changes in HPA axis through release of corticosterone. We determined that mice subjected to restraint stress exhibit significantly elevated corticosterone (the cortisol equivalent in mice). We found that mice stressed for 3 weeks showed an increase in corticosterone from 48.9±34 pg ml−1 to 821.4±326 pg ml−1 (n=5 per group; P=0.027; Figure 6C). We next showed that following a comparison of growth rates, paclitaxel significantly decreased tumour volumes compared with vehicle controls (P<0.0001) restraint stress significantly decreased the efficacy of paclitaxel (P<0.0001) when compared with non-stressed paclitaxel-treated controls (Figure 6D). Furthermore, stress had a significant protective effect in vehicle-treated controls (P=0.047).

Discussion

We have shown that stress hormones not only induce significant DNA damage in TNBC cell lines, but that they induce expression of ATR and p21 in such a way as to regulate progression of the cell cycle, an important factor in the efficacy of drug treatment. Stress hormones were shown to arrest cells in the G0/G1 phase, which would serve to substantiate the decrease in paclitaxel efficacy, which targets cells in the S phase. Increasing levels of stress hormones were also shown to induce p21 via receptor-mediated pathways, suggesting one possible mechanism for this arrest. Two primary signal transducers which regulate DNA damage response pathways are ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM-and Rad3-related (ATR) kinases. The ATM and ATR kinases are differentially activated by distinct types of DNA damage with ATR recruited to single-strand breaks (SSBs) and ATM to double-strand breaks (DSBs), however, ATR also responds to DSBs, and ATM activation can induce ATR activation upon DSB induction (Jazayeri et al, 2006). The ATR regulates Chk1 kinase and its target CDC25 via phosphorylation, thus elevated levels of ATR and pChk1 are indicative of the presence of DNA damage. Elevated levels of ATR and pChk1 suggest that DNA damage recruits ATR and subsequently regulates Chk1 kinase and its target CDC25 via phosphorylation. This implicates that the DNA damage can thereby prevent cell arrest and impact DNA repair. Although the cells we used possess p53 mutations, we also observed DNA damage in cells with wild-type p53 indicating that the effects we observe may occur through both p53-independent and -dependent mechanisms, further work is required to fully understand the role of P53 (Hara et al, 2011).

Through its mediation of ATR, Chk1 and p21 via the GR and ADR receptors, stress hormone levels possess the potential to both increase tumorigenicity and decrease the efficacy of therapeutics, such as paclitaxel, with microtubule stabilizing modes of action.

The role of p21 as a mediator of G1 growth arrest and as an effector of tumour suppressor pathways such as apoptosis has already been well established (Brugarolas et al, 1995). Glucocorticoids also induce cell cycle arrest and increase expression of p21CIP1 (Rogatsky et al, 1997; Heitzer and Defranco, 2006). It has also been shown that glucocorticoids prevent apoptosis in chemotherapeutic-treated breast cancer cells by regulating SGK-1 and MPK-1 kinase activities (Wu et al, 2004). Our findings that a cell line possessing little or no p21 and our p21 knockdown experiments highlight the importance of this molecule in relation to stress and cell cycle halt. It could be argued that MDA-MB-436 cells have lower levels of SH receptors, which could certainly have a part in the failure of stress hormones to induce arrest; however, in cells treated with p21 siRNA, the reduced G1 arrest does suggest a role of p21. Interestingly, we found that paclitaxel increased p21 when G2/M arrest was observed. Paclitaxel stabilises tubulin polymerisation, resulting in arrest at the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and apoptotic cell death. However, the molecular mechanism of this growth inhibition is still poorly understood. Choi and Yu demonstrated that paclitaxel-induced G2/M arrest and apoptosis in MDA-MB 231 cells is mediated through p53-independent up-regulation of p21 (Choi and Yoo, 2012). These studies indicate the complexity of the role of P21 with paclitaxel and stress hormones. The p21 also antithetically promotes oncogenic activity, for example, up-regulation of p21 may actually inhibit apoptosis via cell cycle arrest as the cell must be active to sense the corresponding agents and induce apoptosis (reviewed in (Abbas and Dutta, 2009)). Thus, elevation of p21 by stress hormones via DNA damage may actually promote cell survival and migration in TNBC; further work on this mechanism is undergoing in our laboratory.

Our in vivo data suggest that physical restraint of tumour-bearing mice results in a protective effect in vehicle-treated controls and a decreased efficacy of paclitaxel. The protective effect of stress hormones is intriguing and that in the presence of paclitaxel (which is a well-established inducer of apoptosis (Saunders et al, 1997; Jeansonne et al, 2011; Miller et al, 2013)) stress can inhibit apoptosis through slowing down the cell cycle; whereas in the absence of chemotherapy (and an inducer of apoptosis) stress hormones have an anti-proliferative effect and the tumours grow more slowly.

Current compelling research suggests that RU-486 used in a neoadjuvant setting could increase tumour cell apoptosis in chemotherapy-resistant TNBC (Skor et al, 2013a). Furthermore, a phase II clinical trial using propranolol in addition to chemotherapy in patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer (NLM Identifier NCT01847001) is underway by other researchers. Beta-blockers have also been associated with relapse-free survival in patients with TNBC (Melhem-Bertrandt et al, 2011). However, our data suggest that both ADR and GR have a role in drug resistance and further mechanistic work on the use of both propranolol and RU-486 are warranted. Collectively, these data suggest that stress hormones affect DNA damage and cell cycle regulation in ways that could have profound implications for the efficacy of pharmacotherapy of breast cancer. Paclitaxel and vincristine are unable to work efficiently in cells, which are halted at the G1 phase of the cell cycle thereby promoting drug resistance (Figure 7). A better understanding of the mechanism whereby stress hormones impact drug treatments is critical to propel the development of tailored stress-reduction interventions in patients with breast cancer.

Change history

28 April 2015

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Abbas T, Dutta A (2009) p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 400–414.

Brouckaert O, Wildiers H, Floris G, Neven P (2012) Update on triple-negative breast cancer: prognosis and management strategies. Int J Womens Health 4: 511–520.

Brugarolas J, Chandrasekaran C, Gordon JI, Beach D, Jacks T, Hannon GJ (1995) Radiation-induced cell cycle arrest compromised by p21 deficiency. Nature 377: 552–557.

Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A (2008) Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol 5: 466–475.

Choi YH, Yoo YH (2012) Taxol-induced growth arrest and apoptosis is associated with the upregulation of the Cdk inhibitor, p21WAF1/CIP1, in human breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep 28: 2163–2169.

Chu QD, King T, Hurd T (2012) Triple-negative breast cancer. Int J Breast Cancer 2012: 671684.

Collins AR (2004) The comet assay for DNA damage and repair: principles, applications, and limitations. Mol Biotechnol 26: 249–261.

Dent R, Hanna WM, Trudeau M, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA (2009) Pattern of metastatic spread in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 115: 423–428.

Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA (2007) Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res 13: 4429–4434.

Flint MS, Baum A, Chambers WH, Jenkins FJ (2007) Induction of DNA damage, alteration of DNA repair and transcriptional activation by stress hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32: 470–479.

Flint MS, Baum A, Episcopo B, Knickelbein KZ, Liegey Dougall AJ, Chambers WH, Jenkins FJ (2012) Chronic exposure to stress hormones promotes transformation and tumorigenicity of 3T3 mouse fibroblasts. Stress 16 (1): 114–121.

Flint MS, Bovbjerg DH (2012) DNA damage as a result of psychological stress: implications for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 14: 320.

Flint MS, Budiu RA, Teng PN, Sun M, Stolz DB, Lang M, Hood BL, Vlad AM, Conrads TP (2011) Restraint stress and stress hormones significantly impact T lymphocyte migration and function through specific alterations of the actin cytoskeleton. Brain Behav Immun 25: 1187–1196.

Flint MS, Kim G, Hood BL, Bateman NW, Stewart NA, Conrads TP (2009) Stress hormones mediate drug resistance to paclitaxel in human breast cancer cells through a CDK-1-dependent pathway. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34: 1533–1541.

Flint MS, Miller DB, Tinkle SS (2000) Restraint-induced modulation of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis in male and female B6.129 mice. Brain Behav Immun 14: 256–269.

Hara MR, Kovacs JJ, Whalen EJ, Rajagopal S, Strachan RT, Grant W, Towers AJ, Williams B, Lam CM, Xiao K, Shenoy SK, Gregory SG, Ahn S, Duckett DR, Lefkowitz RJ (2011) A stress response pathway regulates DNA damage through beta2-adrenoreceptors and beta-arrestin-1. Nature 477: 349–353.

Hara MR, Sachs BD, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ (2012) Pharmacological blockade of a beta 2AR-beta-arrestin-1 signaling cascade prevents the accumulation of DNA damage in a behavioral stress model. Cell Cycle 12 (2): 219–224.

Heitzer MD, Defranco DB (2006) Mechanism of action of Hic-5/androgen receptor activator 55, a LIM domain-containing nuclear receptor coactivator. Mol Endocrinol 20: 56–64.

Hermes GL, Delgado B, Tretiakova M, Cavigelli SA, Krausz T, Conzen SD, Mcclintock MK (2009) Social isolation dysregulates endocrine and behavioral stress while increasing malignant burden of spontaneous mammary tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 22393–22398.

Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, Jackson SP (2006) ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol 8: 37–45.

Jeansonne DP, Koh GY, Zhang F, Kirk-Ballard H, Wolff L, Liu D, Eilertsen K, Liu Z (2011) Paclitaxel-induced apoptosis is blocked by camptothecin in human breast and pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol Rep 25: 1473–1480.

Madden KS, Szpunar MJ, Brown EB (2013) Early impact of social isolation and breast tumor progression in mice. Brain Behav Immun 30 Suppl: S135–S141.

Melhem-Bertrandt A, Chavez-Macgregor M, Lei X, Brown EN, Lee RT, Meric-Bernstam F, Sood AK, Conzen SD, Hortobagyi GN, Gonzalez-Angulo AM (2011) Beta-blocker use is associated with improved relapse-free survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29: 2645–2652.

Metzger-Filho O, Tutt A, De Azambuja E, Saini KS, Viale G, Loi S, Bradbury I, Bliss JM, Azim HA Jr., Ellis P, Di Leo A, Baselga J, Sotiriou C, Piccart-Gebhart M (2012) Dissecting the heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 30: 1879–1887.

Miller AV, Hicks MA, Nakajima W, Richardson AC, Windle JJ, Harada H (2013) Paclitaxel-induced apoptosis is BAK-dependent, but BAX and BIM-independent in breast tumor. PLoS One 8: e60685.

Nelson HD, Zakher B, Cantor A, Fu R, Griffin J, O’meara ES, Buist DS, Kerlikowske K, Van Ravesteyn NT, Trentham-Dietz A, Mandelblatt JS, Miglioretti DL (2012) Risk factors for breast cancer for women aged 40 to 49 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 156: 635–648.

Ossovskaya V, Wang Y, Budoff A, Xu Q, Lituev A, Potapova O, Vansant G, Monforte J, Daraselia N (2011) Exploring molecular pathways of triple-negative breast cancer. Genes Cancer 2: 870–879.

Pan D, Kocherginsky M, Conzen SD (2011) Activation of the glucocorticoid receptor is associated with poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res 71: 6360–6370.

Petrella A, Ercolino SF, Festa M, Gentilella A, Tosco A, Conzen SD, Parente L (2006) Dexamethasone inhibits TRAIL-induced apoptosis of thyroid cancer cells via Bcl-xL induction. Eur J Cancer 42: 3287–3293.

Promkan M, Liu G, Patmasiriwat P, Chakrabarty S (2009) BRCA1 modulates malignant cell behavior, the expression of survivin and chemosensitivity in human breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer 125: 2820–2828.

Rogatsky I, Trowbridge JM, Garabedian MJ (1997) Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated cell cycle arrest is achieved through distinct cell-specific transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol 17: 3181–3193.

Rupprecht M, Salzer B, Raum B, Hornstein OP, Koch HU, Riederer P, Sofic E, Rupprecht R (1997) Physical stress-induced secretion of adrenal and pituitary hormones in patients with atopic eczema compared with normal controls. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 105: 39–45.

Rupprecht R, Koch M, Montkowski A, Lancel M, Faulhaber J, Harting J, Spanagel R (1999) Assessment of neuroleptic-like properties of progesterone. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 143: 29–38.

Saunders DE, Lawrence WD, Christensen C, Wappler NL, Ruan H, Deppe G (1997) Paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 breast-cancer cells. Int J Cancer 70: 214–220.

Schmidt P, Holsboer F, Spengler D (2001) Beta(2)-adrenergic receptors potentiate glucocorticoid receptor transactivation via G protein beta gamma-subunits and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Mol Endocrinol 15: 553–564.

Skor MN, Wonder EL, Kocherginsky M, Goyal A, Hall BA, Cai Y, Conzen SD (2013a) Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism as a novel therapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 19: 6163–6172.

Skor MN, Wonder EL, Kocherginsky M, Goyal A, Hall BA, Cai Y, Conzen SD (2013b) Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism as a novel therapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 19 (22): 6163–6172.

Sloan EK, Priceman SJ, Cox BF, Yu S, Pimentel MA, Tangkanangnukul V, Arevalo JM, Morizono K, Karanikolas BD, Wu L, Sood AK, Cole SW (2010) The sympathetic nervous system induces a metastatic switch in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res 70: 7042–7052.

Sood AK, Armaiz-Pena GN, Halder J, Nick AM, Stone RL, Hu W, Carroll AR, Spannuth WA, Deavers MT, Allen JK, Han LY, Kamat AA, Shahzad MM, Mcintyre BW, Diaz-Montero CM, Jennings NB, Lin YG, Merritt WM, Degeest K, Vivas-Mejia PE, Lopez-Berestein G, Schaller MD, Cole SW, Lutgendorf SK (2010) Adrenergic modulation of focal adhesion kinase protects human ovarian cancer cells from anoikis. J Clin Invest 120: 1515–1523.

Sumikawa T, Shigeoka Y, Igishi T, Suyama H, Yamasaki A, Hashimoto K, Matsumoto S, Takeda K, Ueda Y, Shimizu E (2008) Dexamethasone interferes with trastuzumab-induced cell growth inhibition through restoration of AKT activity in BT-474 breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol 32: 683–688.

Thaker PH, Han LY, Kamat AA, Arevalo JM, Takahashi R, Lu C, Jennings NB, Armaiz-Pena G, Bankson JA, Ravoori M, Merritt WM, Lin YG, Mangala LS, Kim TJ, Coleman RL, Landen CN, Li Y, Felix E, Sanguino AM, Newman RA, Lloyd M, Gershenson DM, Kundra V, Lopez-Berestein G, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, Sood AK (2006) Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat Med 12: 939–944.

Thaker PH, Sood AK, Ramondetta LM (2013) Importance of adrenergic pathways in women’s cancers. Cancer Biomark 13: 145–154.

Vazquez SM, Mladovan AG, Perez C, Bruzzone A, Baldi A, Luthy IA (2006a) Human breast cell lines exhibit functional alpha2-adrenoceptors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 58: 50–61.

Vazquez SM, Mladovan AG, Perez C, Bruzzone A, Baldi A, Luthy IA (2006b) Human breast cell lines exhibit functional alpha2-adrenoceptors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 58: 50–61.

Volden PA, Conzen SD (2013) The influence of glucocorticoid signaling on tumor progression. Brain Behav Immun 30: S26–S31.

Wu W, Chaudhuri S, Brickley DR, Pang D, Karrison T, Conzen SD (2004) Microarray analysis reveals glucocorticoid-regulated survival genes that are associated with inhibition of apoptosis in breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res 64: 1757–1764.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Suzanne Conzen for advice and scientific discussion regarding GC signaling and paclitaxel, Drs DeFranco and Peffer for supplying the GR plasmids and Dr Kam Atwal for technical assistance with the western blots. This research was funded by the Pennsylvania Breast Cancer Coalition and Wendy Will Research Fund. This project used the UPCI Biostatistics Shared Resource Facility that is supported, in part, by award P30CA047904.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Reeder, A., Attar, M., Nazario, L. et al. Stress hormones reduce the efficacy of paclitaxel in triple negative breast cancer through induction of DNA damage. Br J Cancer 112, 1461–1470 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.133

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.133

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Chronic stress in solid tumor development: from mechanisms to interventions

Journal of Biomedical Science (2023)

-

Targeting tumor innervation: premises, promises, and challenges

Cell Death Discovery (2022)

-

β-blockers and breast cancer survival by molecular subtypes: a population-based cohort study and meta-analysis

British Journal of Cancer (2022)

-

Effect of chronic stress on tumorigenesis and development

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2022)

-

An integrated framework for quantifying immune-tumour interactions in a 3D co-culture model

Communications Biology (2021)