Abstract

Background:

Care closer to home is being explored as a means of improving patient experience as well as efficiency in terms of cost savings. Evidence that community cancer services improve care quality and/or generate cost savings is currently limited. A randomised study was undertaken to compare delivery of cancer treatment in the hospital with two different community settings.

Methods:

Ninety-seven patients being offered outpatient-based cancer treatment were randomised to treatment delivered in a hospital day unit, at the patient’s home or in local general practice (GP) surgeries. The primary outcome was patient-perceived benefits, using the emotional function domain of the EORTC quality of life (QOL) QLQC30 questionnaire evaluated after 12 weeks. Secondary outcomes included additional QOL measures, patient satisfaction, safety and health economics.

Results:

There was no statistically significant QOL difference between treatment in the combined community locations relative to hospital (difference of −7.2, 95% confidence interval: −19·5 to +5·2, P=0.25). There was a significant difference between the two community locations in favour of home (+15·2, 1·3 to 29·1, P=0.033). Hospital anxiety and depression scale scores were consistent with the primary outcome measure. There was no evidence that community treatment compromised patient safety and no significant difference between treatment arms in terms of overall costs or Quality Adjusted Life Year. Seventy-eight percent of patients expressed satisfaction with their treatment whatever their location, whereas 57% of patients preferred future treatment to continue at the hospital, 81% at GP surgeries and 90% at home. Although initial pre-trial interviews revealed concerns among health-care professionals and some patients regarding community treatment, opinions were largely more favourable in post-trial interviews.

Interpretation:

Patient QOL favours delivering cancer treatment in the home rather than GP surgeries. Nevertheless, both community settings were acceptable to and preferred by patients compared with hospital, were safe, with no detrimental impact on overall health-care costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The demand for cancer services is increasing as a consequence of an ageing population, alongside advances in cancer interventions: there was a 60% increase in the amount of chemotherapy delivered in the UK over a recent 4-year period (Department of Health UK, 2009). Alongside a priority to improve cancer survival rates is the need to improve cancer service quality. The UK health service is committed to giving patients more choice about how, when and where they are treated (Department of Health UK, 2004). Although the vast majority of UK chemotherapy is currently delivered in specialist, high-cost hospitals, the UK health service encourages care closer to home (Department of Health UK, 2006), offering patients greater independence, choice, control and, potentially, better value for money while recognising that the evidence base for such developments is limited (Department of Health UK, 2010).

To date, only five randomised trials have evaluated community delivery of cancer chemotherapy: all are limited by small sample sizes of between 20 and 87 patients. Four trials comparing hospital with home delivery were conducted in Australia (King et al, 2000; Rischin et al, 2000), Spain (Borras et al, 2001) and France (Remonnay et al, 2002). Only one trial was conducted in the UK, comparing a specialist cancer centre with four community hospitals up to 25 miles away (Pace et al, 2009). Four of these trials used a randomised cross-over design, where patients allocated to treatment in one location crossed over within 2 months of starting chemotherapy to the alternative location, patient-reported outcomes being assessed after cross-over. A range of primary outcome measures was used, but some consistent patterns emerged. All studies reported that community care was safe. There was uniform, strong patient preference in favour of treatment in the community (King et al, 2000; Rischin et al, 2000; Borras et al, 2001; Pace et al, 2009). Community treatment was associated with greater (Borras et al, 2001; Pace et al, 2009) or equivalent (King et al, 2000) patient satisfaction, equivalent patient-reported quality of life (QOL; King et al, 2000; Borras et al, 2001), and reduced (Rischin et al, 2000) or equivalent (Pace et al, 2009) patient anxiety.

The cost of delivering community treatment is poorly understood. In the UK, home chemotherapy has hitherto been primarily delivered by the private health-care sector. One UK National Health Service (NHS) hospital explored collaboration with a commercial home care company, but found logistical and clinical governance challenges and concluded that the arrangement was not financially viable (Taylor et al, 2007). Although financial benefits have been reported for home chemotherapy in Tasmania (Lowenthal et al, 1996), four trials have reported higher costs (King et al, 2000; Rischin et al, 2000; Remonnay et al, 2002; Pace et al, 2009), with a suggestion that increased volume of work might make a community service cost-effective (King et al, 2000; Pace et al, 2009). Aside from health service costs, the potential to reduce patients’ personal financial costs through reduced travelling should not be ignored (Pace et al, 2009).

Although most published trials have focused on chemotherapy drug delivery, increasing numbers of patients regularly attend hospital for supportive cancer treatments, including blood transfusions and bisphosphonate infusions, aimed at improving or maintaining quality of life. One trial evaluating community bisphosphonate infusions in breast cancer patients with bone metastases reported significant improvements in pain, general activity, physical, role and social functioning when compared with hospital delivery (Wardley et al, 2005), but financial implications were not addressed.

These various studies justify considering the development of community services for cancer patients receiving any form of treatment currently offered in hospital day units. However, the optimal community model, home versus other community settings, has not been studied. We therefore undertook a trial to directly compare the benefits and costs associated with delivering cancer treatment in two different community settings (home and local general practice (GP) surgeries) with standard hospital day units, in order to inform future service developments.

Methods

The OUTREACH trial was a three-arm, randomised controlled trial conducted in two UK hospitals: Cambridge University Hospitals Foundation Trust (CUH) and West Suffolk Hospital NHS Trust (WSH). The trial had ethics committee approval and was registered as ISRCTN66219681. Full descriptions of the protocol and methods have been published previously (Corrie et al, 2011). In brief, cancer patients over 18 years of age with an ECOG performance status 0–2 and living within a 30-min drive of recruiting hospitals were eligible. Patients who were commencing, or had already commenced, a course of treatment planned to last a minimum of 12 weeks were approached. The treatment was aimed at cure, palliation (disease control and life prolongation) or supportive care (symptom control). The main exclusion criteria were as follows: life expectancy under 6 months; patients dependent on hospital transport; treatment with an unlicensed cancer drug as part of a clinical trial unless approved for community settings; any patient in whom, in the opinion of the investigator, there was a cause for concern regarding patient or staff safety.

Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients recruited to the trial. Patients were randomised to one of three arms as follows: treatment delivered in the hospital outpatient and day unit, the patient’s home or one of three local GP surgeries. Patients were stratified by centre (CUH or WSH), treatment intent (cure, palliation or supportive care), patient performance status (PS 0, 1 or 2), gender and prior cancer drug treatment (yes or no), and randomisation was carried out independently of the trial co-ordination, using the method of minimisation including a random element.

Study interventions

Delivery of treatment in all settings was by the same group of trained chemotherapy nurses employed by the CUH and WSH, according to standard policies and procedures. Patients allocated treatment at a GP surgery were given the choice of one of three local surgeries, all of which had generous, free-parking facilities. Patients did not have to be registered with these practices. Patients were reviewed in clinic before study entry and at 12 weeks as a minimum. Hospital visits, blood tests, radiological investigations and clinician reviews were undertaken on all patients according to standard practice for each disease site and treatment regimen. Study patients used the standard local emergency arrangements as appropriate; community treatment could be transferred to hospital if considered in the patient’s best interest or on patient request.

Outcome measures

The primary end point, patient-reported QOL, was measured using the emotional functional domain of the EORTC QLQC30 questionnaire, completed before randomisation and at 4, 8 and 12 weeks. Other potential patient benefits were measured using the EORTC QLQC30 self-rated health and QOL scores, the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), EQ-5D (EuroQol), and a patient satisfaction questionnaire designed for the trial, completed at the same time points.

The qualitative assessment of the experience of treatment was obtained through semi structured interviews with 11 patients purposively sampled to obtain a maximum variety sample before and after 12 weeks of treatment. Interviews were also held with five Consultant Oncologists, one doctor at each GP surgery, five chemotherapy nurses, two hospital pharmacists and two senior level managers and after the trial. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and entered into QSR International's NVivo 9 software (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2010) for analysis using the Framework approach (Ritchie and Spencer, 1994).

Service use and cost data were collected and cost-effectiveness were assessed by combining service cost data with the primary outcome measure (QLQC30) and Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALYs) generated from the EQ-5D. Each patient’s GP provided information on patient contacts and a summary print out of all prescriptions during the study period.

Patient safety was determined by recording serious adverse events (SAEs), defined as death, life-threatening events, hospital admissions and severe drug-related toxicities; the relatedness of SAEs to treatment delivery venue was assessed. Patients’ reasons for declining to take part or withdrawing from the study were recorded in an optional short, anonymised questionnaire.

Statistical methods

The trial was designed to detect a 10-point difference in mean EORTC QLQC30 emotional function domain in patients between the hospital setting and the combined home and GP surgery community settings. The standard deviation (s.d.) was assumed to be 24, and an allowance of 30% dropout was made for the 12-week primary time point analysis, based on two-sided 5% level significance tests. A total of 130 patients per setting (total 390) was chosen in order to provide 90% power to detect the effect between hospital and combined community settings, and 80% power between the community (home versus GP surgery) settings and other pairs of settings.

Linear regression was chosen to compare continuous outcomes between study arms with an adjustment for baseline value when available (White and Thompson, 2005), in order to provide estimated differences in means with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and this was extended to a linear mixed-effect model with full polynomial terms over time points as a sensitivity analysis in order to assess the robustness of the primary outcome results to missing data. The binomial method was used to estimate exact 95% CI for proportions.

Results

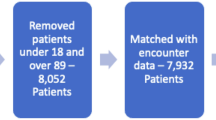

Between January 2009 and May 2011, 97 patients were recruited (Figure 1) to the OUTREACH trial and the three arms were well balanced in terms of baseline characteristics (Table 1). The trial closed prematurely due to poor accrual rate on the advice of the independent data-monitoring committee. Multiple reasons accounted for poor accrual, including uncertainty on the part of health-care staff concerning the community service prior to recruitment starting. The chemotherapy nurses were reluctant to treat patients outside of hospital and found it difficult to staff the new service. Oncologists perceived that patients were better off or safer treated at hospital, or prioritised trials evaluating new therapeutic treatments over service delivery (Table 2). Patients also expressed concerns about taking part in OUTREACH. Fifty-three patients approached to take part in the trial were not prepared to consider the possibility of being treated in any one of the three treatment venues being offered in this trial: 16 clearly indicated a reluctance to accept treatment in a GP surgery, two did not want treatment in their home, while 35 wanted to be treated in hospital.

Despite randomising 97 patients, only 57 patients were eligible for analysis of the primary end point. Six patients failed to start treatment and 17 did not complete the 12 weeks of treatment, mainly due to disease progression. In addition, considerable difficulty was experienced with data collection in all settings. When planning the trial, oncology research nurses were involved in training the chemotherapy delivery nurses to collate the required data and retrieve questionnaires from patients treated in OUTREACH. However, in practice, this strategy, implemented in view of the nature of the study design, was not successful and a considerable amount of data was missed or lost.

For the EORTC QLCQ30 primary outcome, there was no significant difference between treatment in the combined community locations relative to treatment in hospital (difference of −7.2, 95% CI: −19.5 to +5.2, P=0.25). There was, however, a significant difference between the two community locations in favour of home (+15.2, 1.3 to 29.1, P=0.033). Relative to hospital, the outcome was significantly lower in the GP community location, but not in the home community location (Table 3), although CI were wide due to the small sample size. These results were robust to sensitivity analysis in which 78 (80%) contributed 222 primary outcome data values post baseline across time (Table 3 footnote). The HADS scores revealed evidence of a higher mean level of depression in community settings relative to hospital, which reached significance only for the GP arm (difference of 3.29, P=0.01). Despite these findings, 78% of patients expressed satisfaction with their treatment setting, whatever their location. Eighty-two percent of patients expressed a preference for future treatment in the community: the proportions that would prefer any future treatment in the same location were as follows: hospital 57%, GP surgery 81% and home 90%.

The costs of care over the 12-week treatment period were very similar between the three arms, with the GP arm costs being slightly higher than the hospital arm, followed by the home arm (Table 4). The GP arm was also associated with the highest QALY gains, followed by hospital and home. Bearing in mind the small sample size, although delivery of treatment in GP surgeries appeared to be more expensive, it was also more cost-effective than hospital care, with an incremental cost per QALY of £16 235.

With regard to patient safety, only four of 39 SAEs recorded during this study were assessed as being related to treatment setting: two patients (one from each community arm) requested transfer to hospital, one patient forgot to attend the GP surgery and, for one patient due to be treated in their home, their chemotherapy was not ready in time. Both of the latter two patients had subsequent treatment in the community.

Patient and staff interviews before and after the study revealed a wide range of opinions. Most patients who took part in OUTREACH expressed support for treatment in either community setting (Table 5). Clinical staff were concerned about both the patient and staff safety, particularly in the home, whereas hospital and GP surgeries were perceived to be a more secure environment. All groups could see that community treatment offered patients convenience, but raised concerns about affordability. Of note, initial concerns about community treatment appeared to be allayed following the study (Table 6).

Discussion

OUTREACH is the first randomised trial evaluating delivery of cancer treatment in two different community settings. Although it is the largest cohort of patients recruited to a trial evaluating community cancer treatment, the study is underpowered, so the findings need to be interpreted with caution. Our intention had been to randomise a much larger number of patients than was ultimately achieved. Severe difficulties with recruitment were encountered, leading to premature closure of the study. Unique to this trial is the extensive qualitative data generated from interviews with patients and health-care professionals before and after the trial, providing valuable insight regarding barriers to recruitment as well as patients’ priorities for their care. Despite general support from clinical colleagues in both hospitals at the trial design stage, in practice, clinicians were reluctant to refer patients to the trial. Uncertainty over issues of patient and staff safety, cost-efficiency and patient acceptability declared by health-care professionals (Table 2), combined with a primary focus on therapeutic trials, proved to be major obstacles to recruitment that the oncologists leading the trial were unable to overcome. Centralisation of the cancer expertise within specialist centres and professional reluctance to treat patients away from the hospital primarily for safety concerns was cited by Pace et al (2009) as being the root cause of local opposition to their own efforts to undertake a study of community chemotherapy. However, a consistent feature of all studies evaluating cancer treatment in the community, and confirmed in the OUTREACH trial, is a lack of any evidence suggesting safety concerns. Although clinician post-trial interviews indicated many of these objections to have been overcome by positive experience of community treatment, this was not reflected in rising accrual as our trial proceeded. Changes in attitudes and perceptions, sadly, did not lead to changes in behaviour. Patients also had strongly held perceptions of where they wished to be treated, resulting in a high rate of their declining to take part in a three-way randomisation.

For those patients who did take part, our strategy to utilise and train the nursing staff delivering the service to take responsibility for data collection proved disappointing, resulting in missing data that limited the number of complete data sets available for final analysis. When evaluating a service development, it is probably sensible to avoid relying on staff for whom research is not their primary focus, if at all possible. Despite these difficulties limiting its size, the OUTREACH trial provides a major contribution to the current evidence base regarding the evaluation of delivering cancer treatment in the community.

For the QOL primary outcome measure, no statistically significant difference was found between hospital and combined community settings, although treatment in the GP surgery was associated with lower QOL compared with home or hospital. The reasons for this are not clear: the most common reason given by patients who declined to participate or withdrew before starting the treatment was concern regarding the GP surgeries, which were seen as unfamiliar and inconvenient locations. There was also a group of patients who preferred to be treated in the hospital, for reasons of convenience, safety and security. Whether strong preferences existed in patients who were otherwise willing to be randomised in this trial and influenced the QOL results is unknown. The patient satisfaction survey did not identify any difference in patient experience of venue convenience between the hospital and GP arms: only 1 of 15 patients treated in the hospital and 1 of 16 patients treated at the GP surgeries felt that getting to treatment was a problem for them. As previously reported by King et al (2000), most patients were satisfied with their treatment in whichever location it was delivered, with an overriding preference for future treatment in the community.

Health economic analysis revealed no significant difference between settings in terms of costs and QALYs. On the basis of the incremental costs and outcomes of community care compared with hospital care, it appears that the former is cost-effective, as the cost per QALY is below the threshold of £20 000 set by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009). However, both cost and QALY differences may be influenced by the small sample size.

In summary, the OUTREACH trial results provide good evidence to support the development of cancer treatment services in the home, but raises questions regarding the suitability of GP surgeries for this role in terms of QOL measures (EORTC QLQC30 and HADS). Both community settings are acceptable to patients, safe and unlikely to cost more than conventional hospital treatment. The 2010 Department of Health for England commissioner guidance encouraging development of chemotherapy services in the community (Department of Health UK, 2010) suggested 10 potential benefits and seven potential concerns in relation to community cancer treatment, most of which were confirmed in the OUTREACH trial. The two exceptions were that we did not demonstrate reduced health-care costs, neither were there concerns over reduced expert backup support. This trial thus contributes towards the evidence base to inform community cancer treatment service specification and financial models that was previously lacking. It is likely that some patients will have a strong preference for hospital treatment or a particular form of community care. Therefore, patient choice must be addressed.

References

Borras JM, Sanchez-Hernandez A, Navarro M, Martinez M, Mendez E, Ponton JL, Espinas JA, Germa JR (2001) Compliance, satisfaction, and quality of life of patients with colorectal cancer receiving home chemotherapy or outpatient treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Brit Med J 322: 826–829.

Corrie PG, Moody M, Wood V, Bavister L, Prevost T, Parker RA, Sabes-Figuera R, McCrone P, Balsdon H, McKinnon K, O’Sullivan B, Tan RS, Barclay SI (2011) Protocol for the OUTREACH trial: a randomised trial comparing delivery of cancer systemic therapy in three different settings: patient’s home, GP surgery and hospital day unit. BMC Cancer 467: 1–10.

Department of Health (2004) The NHS improvement plan, putting people at the heart of public services. Department of Health: London, UK.

Department of Health (2006) Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for community services. Department of Health: London, UK.

Department of Health (2009) Chemotherapy services in England: ensuring quality and safety. A report from the National Chemotherapy Advisory Group.Department of Health: London, UK.

Department of Health (2010) Chemotherapy services in the community: a guide for PCTs. Department of Health: London, UK.

King MT, Hall J, Caleo S, Gurney HP, Harnett PR (2000) Home or hospital? An evaluation of the costs, preferences, and outcomes of domiciliary chemotherapy. Int J Health Services 30: 557–579.

Lowenthal RM, Piaszczyk A, Arthur GE, O’Malley S (1996) Home chemotherapy for cancer patients: cost analysis and safety. Med J Austral 165: 18–187.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance 2nd (edn). www.nice.org.uk/media/4E9/6A/CPHEMethodsManual.pdf.

Pace E, Dennison S, Morris J, Barton A, Pritchard C, Rule SA (2009) Chemotherapy in the community: what do patients want? Eur J Cancer Care 18: 209–215.

QSR International Pty Ltd. (2010) NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 9.

Remonnay R, Devaux Y, Chauvin F, Dubost E, Carrère MO (2002) Economic evaluation of antineoplasic chemotherapy administered at home or in hospitals. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 18: 508–519.

Rischin D, White MA, Matthews JP, Toner GC, Watty K, Sulkowski AJ, Clarke JL, Buchanan L (2000) A randomised crossover trial of chemotherapy in the home: patient preferences and cost analysis. Med J Austral 173: 125–127.

Ritchie J, Spencer L (1994) Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. in analyzing qualitative data, Bryman A, Burgess RG (eds). pp 173–194. Routledge: London, UK.

Taylor H, Ireland J, Duggan C, Bates I (2007) Home chemotherapy—a feasibility study. Br J Home Healthcare 3: 4–5.

Wardley A, Davidson N, Barrett-Lee P, Hong A, Mansi J, Dodwell D, Murphy R, Mason T, Cameron D (2005) Zoledronic acid significantly improves pain scores and quality of life in breast cancer patients with bone metastases: a randomised, crossover study of community vs hospital bisphosphonate administration. Br J Cancer 92: 1869–1876.

White IR, Thompson SG (2005) Adjusting for partially missing baseline measurements in randomized trials. Stat Med 24: 993–1007.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients who participated in the OUTREACH trial. We are grateful for research and service support obtained from the Cambridge Clinical Trials Unit – Cancer Theme, West Anglia Cancer Research Network and West Anglia Comprehensive Local Research Network, as well as the Cambridge University Hospitals Cancer Division. SB was funded by Macmillan Cancer Support and the NIHR CLAHRC (Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care) for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. ATP was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. This paper presents independent research funded by the NIHR under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0107-12101). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author contributions

PGC and AMM conceived this study. PGC, SB, ATP, PM, RS-F and AMM undertook the design of it. PGC, AMM, LB, HB, KM and BO’S implemented the study. RP and ATP were responsible for participant randomisation. SN, GA, S-HL-S, LB and AH were responsible for data management. AP, RS-F, PM& SB were responsible for data analyses. PC, SB, AtP, PM and RP were responsible for data interpretation. All authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Corrie, P., Moody, A., Armstrong, G. et al. Is community treatment best? a randomised trial comparing delivery of cancer treatment in the hospital, home and GP surgery. Br J Cancer 109, 1549–1555 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.414

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.414

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impacts on health outcomes and on resources utilization for anticancer drugs injection at home, a complex intervention: a systematic review

Supportive Care in Cancer (2021)

-

Randomised trials comparing different healthcare settings: an exploratory review of the impact of pre-trial preferences on participation, and discussion of other methodological challenges

BMC Health Services Research (2016)