Abstract

Background:

Few studies have attempted to characterise genomic changes occurring in hereditary epithelial ovarian carcinomas (EOCs) and inconsistent results have been obtained. Given the relevance of DNA copy number alterations in ovarian oncogenesis and growing clinical implications of the BRCA-gene status, we aimed to characterise the genomic profiles of hereditary and sporadic ovarian tumours.

Methods:

High-resolution array Comparative Genomic Hybridisation profiling of 53 familial (21 BRCA1, 6 BRCA2 and 26 non-BRCA1/2) and 15 sporadic tumours in combination with supervised and unsupervised analysis was used to define common and/or specific copy number features.

Results:

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering did not stratify tumours according to their familial or sporadic condition or to their BRCA1/2 mutation status. Common recurrent changes, spanning genes potentially fundamental for ovarian carcinogenesis, regardless of BRCA mutations, and several candidate subtype-specific events were defined. Despite similarities, greater contribution of losses was revealed to be a hallmark of BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours.

Conclusion:

Somatic alterations occurring in the development of familial EOCs do not differ substantially from the ones occurring in sporadic carcinomas. However, some specific features like extensive genomic loss observed in BRCA1/2 tumours may be of clinical relevance helping to identify BRCA-related patients likely to respond to PARP inhibitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Epithelial ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynaecological malignancy and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death in women in western countries. Due to lack of specific symptoms and effective screening methods, the majority of cases are diagnosed at advanced stages. Since survival probability drops significantly with increasing stage, epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) patients in general face a poor prognosis, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of around 27% (Siegel et al, 2012).

Epithelial ovarian cancer is a very heterogeneous disease that can be stratified using different criteria. Based on molecular and developmental features, EOCs can be divided into type I and type II tumours. Type I tumours arise in a progressive manner from benign, through borderline to low-malignant potential neoplasm. Type II tumours grow rapidly without well-defined premalignant lesions and are typically diagnosed as high-grade serous, high-grade endometroid, or undifferentiated carcinomas depending on the dominant pattern (Kurman and Shih Ie, 2011). Tumours can also be classified as hereditary or sporadic when they arise in patients with or without a family history of the disease, respectively. Overall, around 10–15% of invasive EOCs are estimated to involve hereditary susceptibility (Bast et al, 2009). The majority of these cases are explained by germline mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 tumour suppressor genes (Bast et al, 2009; Pennington and Swisher, 2012) although additional genes such as BRIP1, RAD51C and RAD51D have been recently shown to confer ovarian cancer susceptibility (Pennington and Swisher, 2012). Clinical and histopathological differences between BRCA1- and BRCA2-related tumours and those arising in non-mutation carriers have been reported (Soslow et al, 2012). Importantly, germline BRCA1/2 mutations have been associated with improved survival and chemotherapy response (Alsop et al, 2012; Bolton et al, 2012; Pennington and Swisher, 2012).

It has been suggested that hereditary and sporadic EOCs might evolve in distinct ways, especially due to early homologous recombination (HR) impairment in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (Patael-Karasik et al, 2000; Israeli et al, 2003; Walsh et al, 2008). However, it is still unclear exactly which mechanisms are involved in cancer development in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, and whether they differ from those taking place in sporadic cases. One way to get insight into this issue is to compare the rate and pattern of DNA copy number changes exhibited by these tumour types. This approach is particularly relevant in a view of the results from the recently published Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) study (TCGA, 2011). This the most comprehensive analysis of high-grade EOCs carried out so far revealed that these tumours present a relatively simple mutational spectrum, but are characterised by a large degree of genome instability.

So far few studies have specifically analysed the DNA copy number changes that characterise the different groups of hereditary ovarian tumours (BRCA1, BRCA2 and those from non-BRCA1/2-mutation carriers, also called ‘BRCAX’) or have compared these changes with those observed in sporadic neoplasms (Patael-Karasik et al, 2000; Zweemer et al, 2001; Israeli et al, 2003; Ramus et al, 2003; Leunen et al, 2009). Moreover, the few studies conducted have yielded contradictory results, which might be due to the limited number of tumours included (Patael-Karasik et al, 2000; Israeli et al, 2003; Leunen et al, 2009), the use of low-resolution techniques (Patael-Karasik et al, 2000; Ramus et al, 2003) or the application of different algorithms. Interestingly, the TCGA ovarian study reported that tumours with BRCA1/2 alterations do not exhibit increased genomic instability compared with wild-type tumours (TCGA, 2011). However, that comparison was only made of the total level of DNA copy number alterations with no distinction between gained or lost events. In addition, the TCGA (TCGA, 2011) and other studies (Koul et al, 2000) jointly describe the DNA copy number alterations that occur in tumours carrying germline, somatic and/or epigenetic inactivation of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Nevertheless, it is still not clear whether the mechanisms by which these genes are rendered non-functional might be relevant to the natural history of the tumours and to the changes that arise and are selected throughout the oncogenic process.

Our study addresses some of these limitations by using a homogeneous series of ovarian tumours from patients of well-characterised high-risk breast and ovarian cancer families. Moreover, this series includes not only cases from carriers of germline BRCA1/2 mutations, but also from hereditary BRCAX cases. In addition, we use high-resolution array Comparative Genomic Hybridisation (aCGH) and pay special attention to the separate analysis of gain and loss events. This approach, although still limited, allowed us to obtain further insight into this poorly explored field and to define potential differences and similarities in genomic instability between these tumour groups.

Materials and methods

Additional information can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Patients and tumours

At total of 72 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) epithelial ovarian tumours were analysed. Fifty seven corresponded to patients from high-risk breast and ovarian cancer families and fifteen to sporadic patients. Families selected for this study fulfilled one of the following criteria: (a) at least two cases of ovarian cancer in the same family line; (b) at least one case of ovarian cancer and at least one case of breast cancer in the same family line; (c) at least one woman with both breast and ovarian cancer; (d) at least one woman with bilateral ovarian cancer. Mutation testing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes was carried out using previously described methods (Milne et al, 2008). In total, paraffin blocks from 21 BRCA1, 6 BRCA2 and 30 BRCAX tumours were obtained from different hospitals throughout Spain. Sporadic cases (with no reported first or second degree relative with breast or ovarian cancer), used for comparison purposes, were obtained from a single institution (Hospital Virgen del Rocio, Seville) and were selected to match the distribution of histological subtypes in familial series.

All tumours were blindly reviewed by two pathologists (IMR and JP) and classified histopathologically. Immunohistochemical expression of markers such as Wilms Tumour protein (WT1), tumour protein p53 (TP53), oestrogen receptor (ESR), progesterone receptor (PGR) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (p16) (CDKN2A) was performed to assist in the differential diagnosis (Kobel et al, 2009; Kalloger et al, 2011). Grading of serous tumours was performed according to two-tier MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) system (Malpica et al, 2004; Gilks et al, 2008) while the rest of the histological types was graded according to World Health Organisation criteria (Silverberg, 2000; World Health Organization, 2004). A subgroup of tumours within the type II carcinomas was defined to allow for comparisons between more homogenous groups of high-grade neoplasms. This subgroup consisted of high-grade serous tumours of solid growth pattern and undifferentiated carcinomas (hereafter referred as to ‘subgroup of type II tumours’). Detailed information is shown in Supplementary Table 1. The study was approved by the research ethics committees from each of the participating centres and all patients gave informed consent.

DNA isolation and labelling

Genomic DNA was extracted from three 10-μm-thick FFPE tissue sections per tumour. After deparaffination and rehydration, sections were hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained and tumour areas were delimited by a pathologist and macrodissected with a surgical blade to ensure at least 80% tumour content. DNA extraction was carried according to standard protocol including overnight proteinase K digestion and using QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Westburg, Leusden, The Netherlands) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Labelling of test and reference DNA was performed with the Enzo Genomic DNA labeling kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) as described previously. In 45 out of 72 hybridisations (62%), patient-matched normal DNA was used as a reference (in 26 from conserved normal tissue and in 19 from the patient’s peripheral blood). In the remaining 27 hybridizations (38%), a pool of normal DNA from healthy females was used as a reference (http://www.kreatech.com/products/megapool-reference-dna.html).

Hybridisations, scanning and image acquisition

Hybridisations were performed on slides of four arrays, each containing 180 880 in situ synthesised 60-mer oligonucleotides (4 × 180 K, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) representing 169 793 unique chromosomal locations evenly distributed across the genome (space∼17 kb), and 4548 additional unique oligonucleotides, located at 238 of the Cancer Census genes (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/Census/). Oligonucleotide positions were defined according to the NCBI36/hg18 assembly (March 2006). Hybridisation, scanning and feature extraction were carried out as previously described (Buffart et al, 2008). The aCGH data have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al, 2002) and are accessible through GEO accession number GSE41253 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE41253).

Preprocessing and processing

Data normalisation, segmentation and calling were performed in R (v.2.8.2 and 2.13; http://www.r-project.org), using median normalisation and Wave Smoothing and CGH-call packages (van de Wiel and Zhang, 2007). For visualisation and downstream processing, data were analysed in Nexus Copy Number v5.1 (BioDiscovery, Inc., El Segundo, CA, USA). The WECCA (Weighted Clustering of Called aCGH Data) R package (Van Wieringen et al, 2008) was used for unsupervised hierarchical clustering (total linkage and overall similarity algorithms).

Degree of genomic instability: number and length of alterations

To determine the degree of genomic instability in each subgroup of tumours (BRCA1/2/X and sporadic), total number of alterations and of a particular type (homozygous deletions (HDs)/losses/gains/amplifications) were calculated per sample. Total size of altered genome and size accounted for by gains and losses was calculated by adding up the lengths of individual segments. Next, average number of changes and average size of altered genome were calculated for sporadic tumours and for each group of familial tumours. To determine the relative contribution of each type of change (losses or gains), the ratio of the average number of losses to the average number of gains within each tumour subtype was computed. Similarly, the ratio of the average length of the lost genome to the average length of gained was calculated.

Common and potentially specific regions of copy number changes

To visualise the general pattern of chromosomal changes, frequency plots and a list of recurrent minimal common regions (MCRs) of alterations were generated for each tumour subtype (BRCA1/2/X and sporadic) using Nexus Copy Number v5.1 (BioDiscovery, Inc.). Potentially group-specific alterations were defined using Fisher's Exact Test (FET) (P-value<0.05) implemented in Nexus and chi-square test within CGHtest (R package) with correction for multiple testing (FDR<0.02).

The list of potentially group-specific regions was further refined using data from the TCGA ovarian study (TCGA, 2011) as described in Supplementary Materials.

Immunohistochemical analysis

To validate our hybridisation and analytical approaches, we selected three high-amplitude events (HDs at the CDKN2A and RB1 loci and amplification at the CCNE1 locus) to determine the consistency between the assigned DNA copy number status and the expression levels of the target proteins. Details are explained in Supplementary Materials and shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparison of continuous variables (number and size of alterations between different tumour groups and clusters) was done using Student’s two-tailed t-test (for variables of normal distribution) or the Mann–Whitney test (non-parametric distributions). For categorical data (FIGO stage, BRCA1/2 mutation status, etc.), chi-square or Fisher’s Exact Test were applied, depending on the size of the compared groups.

Results

Tumour characteristics

In our series of 57 familial tumours, 4 were classified as borderline lesions and 53 corresponded to carcinomas. The borderline tumours were analysed separately (data not shown) and excluded from this study. All of them belonged to the BRCAX group. Most tumours from BRCA1/2 mutation carriers were serous, high grade and high FIGO stage. In contrast, BRCAX tumours were more heterogeneous and presented a wider range of histological subtypes and stages. As expected, hereditary patients were diagnosed at a significantly younger age than sporadic ones (51 vs 62 years, P=0.001). Patient and tumour characteristics are summarised in Supplementary Table 1.

Number and length of copy number alteration across tumour subtypes

Overall, the pattern of copy number alterations was not substantially different between familial (all subtypes) and sporadic tumours (Figure 1A). Likewise, there were no significant differences between familial and sporadic tumours regarding the average total number of alterations and the average total length of genome altered per tumour (considering all carcinomas and the subgroup of type II neoplasms, the latter defined as described in Materials and methods) (Supplementary Table S3). Both familial and sporadic tumours were characterised by a high level of genomic instability, which in the subgroup of type II carcinomas was exemplified by an average of >60 aberrations per tumour that involved >1 Mb of the genome (Supplementary Table S3). Despite this general similarity, a separate analysis of gains and losses and stratification of familial tumours according to their BRCA1/2 mutation status revealed some differences.

(A ) Frequency plots of copy number gains (in green) and losses (in red) defined in all carcinomas and subgroups. The proportion of tumours with gained/lost regions is plotted on the y axis versus genomic location on the x axis. Common recurrently altered regions across all four subgroups or present in >55% of the whole series are marked with black arrows on the general plot (for all series), while group-specific regions identified for sporadic, BRCA1 and BRCAX tumours are identified on the corresponding plots with blue arrows. Simplified chromosomal locations are given next to the arrows (using the same colour code). (B) Dendrograms derived from unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on copy number alterations of epithelial ovarian carcinomas (n=68) (left panel) and a subgroup of type II carcinomas (n=31) (right panel) with colour labels defining the familial or sporadic condition of the tumour as well as the BRCA gene mutation status of the sample.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours presented a greater average number of losses and HDs than sporadic or BRCAX tumours, while sporadic cases presented the highest average number of gains and amplifications of all tumour subtypes (Figure 2A; Supplementary Table S3). A similar pattern was observed when only high-grade tumours were considered (Figure 2B; Supplementary Table S3). Comparisons of gains and losses within each tumour subtype revealed that sporadic tumours presented a similar average number of both events (25.7 vs 25.6, respectively). However, in familial tumours the average number of losses was 1.4 times greater than the average number of gains, with differences mostly attributed to BRCA1 (29.6 losses vs 21.7 gains, P=0.02) and BRCA2 tumours (32.7 losses vs 14.5 gains, P=0.009) (Figure 2C; Supplementary Table S3). This was also observed in the subgroup of type II tumours, with significant and borderline significant differences between numbers of gains and losses in BRCA2 and BRCA1 tumours, respectively (Figure 2D; Supplementary Table S3).

Average number ( A – D ) and length ( E – H ) of copy number alterations in different groups of ovarian carcinomas ( A, C, E, D ) and a subgroup of type II carcinomas ( B, D, F, H). Significant differences in number and length of alterations between (A, B, E, F) and within (C, D, G, H) tumour groups are indicated with *(P<0.05) or **(P<0.01). Error bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals. aSubgroup of type II carcinomas as defined in Materials and methods.

In agreement with the analysis of the number of alterations, we found that BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours presented a significantly higher average length of genome altered due to losses than sporadic or BRCAX tumours (Figure 2E; Supplementary Table S3). This pattern was partially maintained in the subgroup of type II carcinomas, with significant differences between tumours from BRCA2 and BRCAX patients (Figure 2F; Supplementary Table S3). Interestingly, in all tumour subtypes, including the sporadic group, which showed similar average numbers of both alterations, more genetic material was lost than gained (Figures 2G and H; Supplementary Table S3). In BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours, the average length of lost genome was 2.1 and 3.8-fold greater than the length of gained material, respectively. In sporadic and BRCAX tumours, differences were less marked (1.6-fold in both) (Figure 2G; Supplementary Table S3). Differences between length of genome gained and lost per tumour were statistically significant in all familial tumours (BRCA1, BRCA2 and BRCAX), while only a trend was observed in sporadic cases (P=0.09). In the subgroup of type II tumours, only differences in BRCA1/2 carriers remained significant (P<0.001) (Figure 2H; Supplementary Table S3).

Common and group-specific copy number alterations

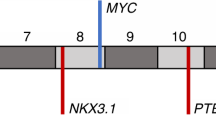

A summary of common gains and losses identified as recurrent in at least three of the analysed tumour subtypes (BRCA1, BRCA2, BRCAX and sporadic) is shown in Table 1. Regions recurrently gained in the four tumour subtypes were 6p25.3, 8q24.2-q24.3 and 12p13.33-p13.32, and regions exhibiting the highest frequencies were 3q26.2 and 8q24.2-q24.3 (Figure 1A–I; Table 1). These regions and others defined as recurrently gained included from 1 up to 45 genes and spanned well-known or potential oncogenes such as MECOM, PIK3CA, FOXQ1, MYC, CCND2 and CANT1. Regions recurrently lost in all four subgroups were defined at 9p24.3, 9p21.3, 17q11.2-q12, 22q12.3, 22q13.1 and 22q13.31-q13.33. Alterations of the highest incidence were found at 8p23.3-p23.1 and 17p13.3-p11.2 (Figure 1A–I; Table 1). Many of these deleted regions and the others qualifying as recurrent across tumour subtypes encompassed tumour suppressors previously linked to ovarian carcinogenesis (e.g., MCPH1, CDKN2A, CDKN2B and NF1). However, other regions pointed to less well-characterised suppressors not previously associated with ovarian cancer (e.g., FANCC, TSC1, CREBBP, CDH11 and EDA2R).

Despite the similar profile of copy number changes exhibited by hereditary and sporadic tumours, supervised analysis unveiled some regions potentially associated with particular tumour subtypes (FDR<0.2) (Figure 1A; Supplementary Table S4). Among the alterations more recurrently found in BRCA1 tumours compared with sporadic cases were losses at 4q32.3-q34.1, 6q22.33-q26 or 12q21.2-q23.2 (Figure 1A and IV) while gains at 6p12-p11, 10p14-p11 and 10q22 were found to be more frequent in BRCAX tumours (compared with BRCA1 cases; Figure 1A and IV). Gains at 2p23.3, 12p11.22-p11.1 and 19q12-q13.11 were identified more recurrently in sporadic cases (Figure 1A and II), with the latter containing the CCNE1 gene that was also amplified in these tumours.

High level amplifications and HDs

The high resolution of our platform allowed us to identify focal high-amplitude copy number changes. Fifty-nine narrow amplifications (median length of 739 Kb spanning on average 11 genes) were identified in at least two cases (Supplementary Table S5, part A). For instance amplification at 8q22.1, found only in BRCA1 tumours, presented a MCR that spanned just one gene, the cancer-associated LAPTM4B. The most frequent regions of amplification with their distributions across the groups of tumours are shown in Table 2. In addition, 57 focal HDs (median length of 465 Kbp spanning 6 genes on average) were identified in at least 2 samples (Table 2; Supplementary Table S5, part B). The two most common HDs (9% each) present in all tumour groups were found at 17q11.2 and 13q14.2; each deletion encompassed only one gene (NF1 and RB1, respectively). Other frequent HDs common for sporadic and familial tumours were defined at 8p23.2-p23.1, spanning the early DNA damage-response gene MCPH1, and at the fragile site on chromosome 3 (3p14.2) containing the known tumour suppressor FHIT.

Immunohistochemical validation of aCGH results

To validate our aCGH results, we assessed the correlation between the assigned DNA copy number and the immunohistochemical expression of three genes targeted by high-amplitude events: CDKN2A and RB1 located at homozygously deleted regions, and CCNE1 that was found amplified. Immunohistochemical analysis showed complete lack or much lower expression of CDKN2A and RB1 in tumours with HD at these loci compared with the mean value of samples with a flat profile at 9p21.3 and 13q14.2, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1A and B). Tumours exhibiting CCNE1 amplification presented much higher expression compared with the mean value of tumours with normal DNA copy number at this locus (Supplementary Figure S1C).

Unsupervised analysis

In addition to systematic comparison of copy number alterations across different tumour subtypes, we also carried out unsupervised analysis of the aCGH data to unveil possible associations between particular patterns of genomic changes and the sporadic or familial status of tumours (or hereditary subtype, BRCA1/2/X). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering stratified ovarian carcinomas (n=68), based on their copy number changes, into two main clusters (A and B) (Figure 1B, left panel). Significant differences were not found between tumours from both clusters (or from smaller subgroups) either according to their general familial or sporadic condition or according to their specific BRCA mutation status. In contrast, clustering was associated with genomic instability level, FIGO stage and histological subtype. The cluster with more genomically instable tumours (cluster B) was significantly enriched in high FIGO stage (P=0.03) and serous type carcinomas (vs all other subtypes, P=0.001). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the subgroup of type II tumours (n=31) also rendered two clusters (II-A and II-B) without significant enrichment in tumours from particular BRCA subgroups (Figure 1B, right panel).

Discussion

Few studies have addressed the characterisation of DNA copy number changes arising in hereditary ovarian tumours, especially in comparison with more extensively studied familial breast tumours (Hedenfalk et al, 2003; Gronwald et al, 2005; Jonsson et al, 2005; Mangia et al, 2008; Melchor et al, 2008; Joosse et al, 2009; Stefansson et al, 2009; Waddell et al, 2010; Didraga et al, 2011; Focken et al, 2011). The few existing studies have rendered contradictory results, either supporting that mutations in BRCA1/2 affect the particular chromosomal alterations occurring throughout cancer progression (Ramus et al, 2003, 2007), or reporting very few copy number changes specifically associated to tumours harbouring such mutations (Israeli et al, 2003; TCGA, 2011). Given these antecedents, the recently confirmed relevance of copy number changes as drivers of ovarian oncogenesis (TCGA, 2011) and the growing clinical implications of the BRCA1/2 mutation status, we aimed to determine how hereditary and sporadic ovarian tumours relate to genomic instability and to define common and/or distinct events occurring in the genesis and evolution of these neoplasms. Different from most prior studies, we analysed tumours not only from carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations, but also from non-BRCA1/2 hereditary patients (BRCAX tumours) as these have been particularly poorly characterised. Also, we used a high-resolution aCGH platform and separately analysed gains and losses (in contrast to other studies correlating BRCA1/2 impairment only with global instability).

Our findings indicate lack of substantial differences in the pattern of DNA copy number changes displayed by sporadic carcinomas and the different subtypes of familial tumours. This similarity was illustrated by the existence of shared regions found to be recurrently altered in each individual group of tumours. These common events point to the involvement of genes fundamental for ovarian carcinogenesis, selected throughout the evolution of the tumours and providing advantage to any cancer cell, independently of the existence of germinal mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes. As possible candidates, we found known players previously related to EOC such as PIK3CA, MECOM, MYC, NF1 and RB, but also less characterised genes, whose gains of function (CDH12, FOXQ1, TXNDC5, CCND2, FOXJ1) and/or abrogation (FANCC, TSC1, CREBBP, CDH11, EDA2R) might be crucial for ovarian cancer development and/or progression. Exploration of the therapeutic opportunities provided by these targets, to which a majority of tumours are likely to be addicted, is an attractive possibility. For instance, it has been suggested that modulation of cellular activities of the forkhead transcription factor FOXQ1 may have an application in cancer therapy since its inhibition blocks epithelial to mesenchymal transition and results in cancer cell sensitisation to a variety of chemotherapeutic agents (Qiao et al, 2011). Therapeutic approaches based on repression of cyclin D gene have also been investigated (Tiedemann et al, 2008; Dong et al, 2010) and may be applicable to EOCs presenting aberrant CCND2 expression due to DNA-copy number gains. Likewise, m-TORC1-directed therapies may be more effective in cancer patients whose tumours present TSC1 (tuberous sclerosis complex 1) genomic losses as it has been proposed for patients whose tumour harbour TSC1 somatic mutations (Iyer et al, 2012).

Also exemplifying the absence of marked differences in the profile of genomic changes of carriers and non-carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations, unsupervised hierarchical clustering did not stratify tumours according to their familial or sporadic condition, nor did it according to their BRCA1/2 mutation status. This is different from what has been reported on familial BRCA1 and BRCA2 breast tumours, which show association with particular molecular subtypes (defined with expression arrays) and specific patterns of copy number changes (Jonsson et al, 2005; Bergamaschi et al, 2006; Melchor et al, 2008; Stefansson et al, 2009). Lack of segregation of ovarian tumours from carriers and non-carriers of BRCA1/2 germline mutations based on their genomic instability pattern would support a model according to which HR repair loss (through inactivation of the BRCA1/2 genes or other members of the pathway) would not only be a frequent event in high-grade serous ovarian tumours, as recently demonstrated (TCGA, 2011), but also an event occurring in the initial phases of tumour growth.

Interestingly, despite this general picture of similarity between sporadic and hereditary tumours, differences concerning the overall degree of genomic instability were revealed when gains and losses were analysed separately. Copy number losses were particularly abundant in BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours, both in global terms (comparison of losses made across tumour subtypes) and relative to the number of gains (comparison within each tumour subtype). Although greater contribution of losses than gains was observed in all tumour subtypes, the extent of this phenomenon was more prominent in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Some prior studies, including the most comprehensive one conducted by the TCGA Research network in high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas, reported no differences in the global degree of instability between tumours with BRCA1/2 inactivating events and those with functional BRCA1/2 genes (TCGA, 2011; Ramus et al, 2003). However, no distinction was made between gains and losses, and only comparison of total changes was conducted. Earlier studies already suggested the relevance of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in ovarian tumours from BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers (Walsh et al, 2008; Leunen et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2012), but included very few familial cases (Walsh et al, 2008; Leunen et al, 2009) or used low-resolution platforms (Leunen et al, 2009). Our results derived from analysis made across tumour types, within each tumour subgroup and particularly when taking into account only high-grade tumours highlight the relevance of genomic loss in BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours, a phenomenon that would not merely reflect differences related to the higher grade or more prevalent serous histotype of hereditary tumours. Interestingly, correlation between extent of LOH and therapy sensitivity has been recently reported in high-grade serous ovarian tumours (Wang et al, 2012).

Our findings suggest that in the oncogenesis of ovarian tumours, and in particular of hereditary BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours, loss of function of tumour suppressor genes might be under greater selection pressure than gain of function of proto-oncogenes, at least through DNA copy number-related mechanisms. However, lack of clear segregation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours in the unsupervised analysis would indicate that most of the genomic loss in carriers does not involve a defined group of critical regions (or specific suppressor genes) recurrently selected during evolution of these particular tumours. Alternatively, greater involvement of loss events in ovarian tumours might be related to impairment of HR function, with grosser effects in BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumours due to the central role played by both genes within the pathway.

Although a consistent distinct pattern of copy number changes does not seem to characterise BRCA1 and BRCA2 hereditary ovarian tumours, we were able to define several individual regions potentially associated with BRCA1 tumours (mainly losses) and a few other aberrations (gains and amplifications) potentially associated with sporadic tumours. For instance, losses defined at 4q32.1-q35.2, 13q13.3-q14.3, 17q11.1-q11.2, 17q12, 17q21.32-q21.33, 17q24.3-q25.1 and 22q13.31 found to be related more specifically to BRCA1 cases in our series, were also previously reported to be associated with this tumour group (Zweemer et al, 2001; Ramus et al, 2003; Domanska et al, 2010). The ovarian TCGA study reported only two regions being significantly enriched in one tumour subtype, amplifications at 19p13.13 and 19q12 associated with sporadic tumours (vs BRCA-altered tumours). Interestingly, gains and amplifications at 19q12 encompassing CCNE1 were also defined as potentially associated with sporadic tumours in our analysis. This finding reinforces the proposed role for CCNE1 and of other proteins implicated in cell-cycle progression as important contributors to ovarian carcinogenesis in tumours with intact BRCA function (Bowtell, 2010; TCGA, 2011; Berns and Bowtell, 2012)

In summary, we have performed a comprehensive analysis of the DNA-copy number changes that occur in hereditary EOCs. We have found that overall hereditary and sporadic EOCs exhibit a similar pattern of DNA copy number alterations. However, greater contribution of losses was revealed to be a hallmark of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Importantly, this feature may help to identify BRCA-related patients who have been shown to respond to PARP inhibitors and to present better prognosis when treated with standard regimes.

Accession codes

Change history

30 April 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, Defazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, Dobrovic A, Birrer MJ, Webb PM, Stewart C, Friedlander M, Fox S, Bowtell D, Mitchell G (2012) BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian ovarian cancer study group. J Clin Oncol 30: 2654–2663.

Bast RC Jr, Hennessy B, Mills GB (2009) The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for translation. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 415–428.

Bergamaschi A, Kim YH, Wang P, Sorlie T, Hernandez-Boussard T, Lonning PE, Tibshirani R, Borresen-Dale AL, Pollack JR (2006) Distinct patterns of DNA copy number alteration are associated with different clinicopathological features and gene-expression subtypes of breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 45: 1033–1040.

Berns EM, Bowtell DD (2012) The changing view of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 72: 2701–2704.

Bolton KL, Chenevix-Trench G, Goh C, Sadetzki S, Ramus SJ, Karlan BY, Lambrechts D, Despierre E, Barrowdale D, McGuffog L, Healey S, Easton DF, Sinilnikova O, Benitez J, Garcia MJ, Neuhausen S, Gail MH, Hartge P, Peock S, Frost D, Evans DG, Eeles R, Godwin AK, Daly MB, Kwong A, Ma ES, Lazaro C, Blanco I, Montagna M, D'Andrea E, Nicoletto MO, Johnatty SE, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Hogdall E, Goode EL, Fridley BL, Loud JT, Greene MH, Mai PL, Chetrit A, Lubin F, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Glendon G, Andrulis IL, Toland AE, Senter L, Gore ME, Gourley C, Michie CO, Song H, Tyrer J, Whittemore AS, McGuire V, Sieh W, Kristoffersson U, Olsson H, Borg A, Levine DA, Steele L, Beattie MS, Chan S, Nussbaum RL, Moysich KB, Gross J, Cass I, Walsh C, Li AJ, Leuchter R, Gordon O, Garcia-Closas M, Gayther SA, Chanock SJ, Antoniou AC, Pharoah PD (2012) Association between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and survival in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA 307: 382–390.

Bowtell DD (2010) The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 10: 803–808.

Buffart TE, Israeli D, Tijssen M, Vosse SJ, Mrsic A, Meijer GA, Ylstra B (2008) Across array comparative genomic hybridization: a strategy to reduce reference channel hybridizations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 47: 994–1004.

Didraga MA, van Beers EH, Joosse SA, Brandwijk KI, Oldenburg RA, Wessels LF, Hogervorst FB, Ligtenberg MJ, Hoogerbrugge N, Verhoef S, Devilee P, Nederlof PM (2011) A non-BRCA1/2 hereditary breast cancer sub-group defined by aCGH profiling of genetically related patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130: 425–436.

Domanska K, Malander S, Staaf J, Karlsson A, Borg A, Jonsson G, Nilbert M (2010) Genetic profiles distinguish different types of hereditary ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep 24: 885–895.

Dong Q, Meng P, Wang T, Qin W, Wang F, Yuan J, Chen Z, Yang A, Wang H (2010) MicroRNA let-7a inhibits proliferation of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by targeting E2F2 and CCND2. PLoS ONE 5: e10147.

Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE (2002) Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 207–210.

Focken T, Steinemann D, Skawran B, Hofmann W, Ahrens P, Arnold N, Kroll P, Kreipe H, Schlegelberger B, Gadzicki D (2011) Human BRCA1-associated breast cancer: no increase in numerical chromosomal instability compared to sporadic tumors. Cytogenet Genome Res 135: 84–92.

Gilks CB, Ionescu DN, Kalloger SE, Kobel M, Irving J, Clarke B, Santos J, Le N, Moravan V, Swenerton K (2008) Tumor cell type can be reproducibly diagnosed and is of independent prognostic significance in patients with maximally debulked ovarian carcinoma. Hum Pathol 39: 1239–1251.

Gronwald J, Jauch A, Cybulski C, Schoell B, Bohm-Steuer B, Lener M, Grabowska E, Gorski B, Jakubowska A, Domagala W, Chosia M, Scott RJ, Lubinski J (2005) Comparison of genomic abnormalities between BRCAX and sporadic breast cancers studied by comparative genomic hybridization. Int J Cancer 114: 230–236.

Hedenfalk I, Ringner M, Ben-Dor A, Yakhini Z, Chen Y, Chebil G, Ach R, Loman N, Olsson H, Meltzer P, Borg A, Trent J (2003) Molecular classification of familial non-BRCA1/BRCA2 breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 2532–2537.

Israeli O, Gotlieb WH, Friedman E, Goldman B, Ben-Baruch G, Aviram-Goldring A, Rienstein S (2003) Familial vs sporadic ovarian tumors: characteristic genomic alterations analyzed by CGH. Gynecol Oncol 90: 629–636.

Iyer G, Hanrahan AJ, Milowsky MI, Al-Ahmadie H, Scott SN, Janakiraman M, Pirun M, Sander C, Socci ND, Ostrovnaya I, Viale A, Heguy A, Peng L, Chan TA, Bochner B, Bajorin DF, Berger MF, Taylor BS, Solit DB (2012) Genome sequencing identifies a basis for everolimus sensitivity. Science 338: 221.

Jonsson G, Naylor TL, Vallon-Christersson J, Staaf J, Huang J, Ward MR, Greshock JD, Luts L, Olsson H, Rahman N, Stratton M, Ringner M, Borg A, Weber BL (2005) Distinct genomic profiles in hereditary breast tumors identified by array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res 65: 7612–7621.

Joosse SA, van Beers EH, Tielen IH, Horlings H, Peterse JL, Hoogerbrugge N, Ligtenberg MJ, Wessels LF, Axwijk P, Verhoef S, Hogervorst FB, Nederlof PM (2009) Prediction of BRCA1-association in hereditary non-BRCA1/2 breast carcinomas with array-CGH. Breast Cancer Res Treat 116: 479–489.

Kalloger SE, Kobel M, Leung S, Mehl E, Gao D, Marcon KM, Chow C, Clarke BA, Huntsman DG, Gilks CB (2011) Calculator for ovarian carcinoma subtype prediction. Mod Pathol 24: 512–521.

Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Carrick J, Huntsman D, Asad H, Oliva E, Ewanowich CA, Soslow RA, Gilks CB (2009) A limited panel of immunomarkers can reliably distinguish between clear cell and high-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol 33: 14–21.

Koul A, Malander S, Loman N, Pejovic T, Heim S, Willen R, Johannsson O, Olsson H, Ridderheim M, Borg AA (2000) BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ovarian cancer: Covariation with specific cytogenetic features. Int J Gynecol Cancer 10: 289–295.

Kurman RJ, Shih Ie M (2011) The origin and pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer: a proposed unifying theory. Am J Surg Pathol 34: 433–443.

Leunen K, Gevaert O, Daemen A, Vanspauwen V, Michils G, De Moor B, Moerman P, Vergote I, Legius E (2009) Recurrent copy number alterations in BRCA1-mutated ovarian tumors alter biological pathways. Hum Mutat 30: 1693–1702.

Malpica A, Deavers MT, Lu K, Bodurka DC, Atkinson EN, Gershenson DM, Silva EG (2004) Grading ovarian serous carcinoma using a two-tier system. Am J Surg Pathol 28: 496–504.

Mangia A, Chiarappa P, Tommasi S, Chiriatti A, Petroni S, Schittulli F, Paradiso A (2008) Genetic heterogeneity by comparative genomic hybridization in BRCAx breast cancers. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 182: 75–83.

Melchor L, Honrado E, Garcia MJ, Alvarez S, Palacios J, Osorio A, Nathanson KL, Benitez J (2008) Distinct genomic aberration patterns are found in familial breast cancer associated with different immunohistochemical subtypes. Oncogene 27: 3165–3175.

Milne RL, Osorio A, Cajal TR, Vega A, Llort G, de la Hoya M, Diez O, Alonso MC, Lazaro C, Blanco I, Sanchez-de-Abajo A, Caldes T, Blanco A, Grana B, Duran M, Velasco E, Chirivella I, Cardenosa EE, Tejada MI, Beristain E, Miramar MD, Calvo MT, Martinez E, Guillen C, Salazar R, San Roman C, Antoniou AC, Urioste M, Benitez J (2008) The average cumulative risks of breast and ovarian cancer for carriers of mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 attending genetic counseling units in Spain. Clin Cancer Res 14: 2861–2869.

Patael-Karasik Y, Daniely M, Gotlieb WH, Ben-Baruch G, Schiby J, Barakai G, Goldman B, Aviram A, Friedman E (2000) Comparative genomic hybridization in inherited and sporadic ovarian tumors in Israel. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 121: 26–32.

Pennington KP, Swisher EM (2012) Hereditary ovarian cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Gynecol Oncol 124: 347–353.

Qiao Y, Jiang X, Lee ST, Karuturi RK, Hooi SC, Yu Q (2011) FOXQ1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human cancers. Cancer Res 71: 3076–3086.

Ramus SJ, Harrington PA, Pye C, DiCioccio RA, Cox MJ, Garlinghouse-Jones K, Oakley-Girvan I, Jacobs IJ, Hardy RM, Whittemore AS, Ponder BA, Piver MS, Pharoah PD, Gayther SA (2007) Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to inherited ovarian cancer. Hum Mutat 28: 1207–1215.

Ramus SJ, Pharoah PD, Harrington P, Pye C, Werness B, Bobrow L, Ayhan A, Wells D, Fishman A, Gore M, DiCioccio RA, Piver MS, Whittemore AS, Ponder BA, Gayther SA (2003) BRCA1/2 mutation status influences somatic genetic progression in inherited and sporadic epithelial ovarian cancer cases. Cancer Res 63: 417–423.

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2012) Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 62: 10–29.

Silverberg SG (2000) Histopathologic grading of ovarian carcinoma: a review and proposal. Int J Gynecol Pathol 19: 7–15.

Soslow RA, Han G, Park KJ, Garg K, Olvera N, Spriggs DR, Kauff ND, Levine DA (2012) Morphologic patterns associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 genotype in ovarian carcinoma. Mod Pathol 25: 625–636.

Stefansson OA, Jonasson JG, Johannsson OT, Olafsdottir K, Steinarsdottir M, Valgeirsdottir S, Eyfjord JE (2009) Genomic profiling of breast tumours in relation to BRCA abnormalities and phenotypes. Breast Cancer Res 11: R47.

TCGA (2011) Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474: 609–615.

Tiedemann RE, Mao X, Shi CX, Zhu YX, Palmer SE, Sebag M, Marler R, Chesi M, Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Schimmer AD, Stewart AK (2008) Identification of kinetin riboside as a repressor of CCND1 and CCND2 with preclinical antimyeloma activity. J Clin Invest 118: 1750–1764.

van de Wiel DF, Zhang WL (2007) Identification of pork quality parameters by proteomics. Meat Sci 77: 46–54.

Van Wieringen WN, Van De Wiel MA, Ylstra B (2008) Weighted clustering of called array CGH data. Biostatistics 9: 484–500.

Waddell N, Arnold J, Cocciardi S, da Silva L, Marsh A, Riley J, Johnstone CN, Orloff M, Assie G, Eng C, Reid L, Keith P, Yan M, Fox S, Devilee P, Godwin AK, Hogervorst FB, Couch F, Grimmond S, Flanagan JM, Khanna K, Simpson PT, Lakhani SR, Chenevix-Trench G (2010) Subtypes of familial breast tumours revealed by expression and copy number profiling. Breast Cancer Res Treat 123: 661–677.

Walsh CS, Ogawa S, Scoles DR, Miller CW, Kawamata N, Narod SA, Koeffler HP, Karlan BY (2008) Genome-wide loss of heterozygosity and uniparental disomy in BRCA1/2-associated ovarian carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 14: 7645–7651.

Wang ZC, Birkbak NJ, Culhane A, Drapkin RI, Fatima A, Tian R, Schwede M, Alsop K, Daniels KE, Piao H, Liu J, Etemadmoghadam D, Miron A, Salvesen HB, Mitchell G, Defazio A, Quackenbush J, Berkowitz RS, Iglehart JD, Bowtell DD, Matulonis UA (2012) Profiles of genomic instability in high-grade serous ovarian cancer predict treatment outcome. Clin Cancer Res 18: 5806–5815.

World Health Organization (2004) Histological Typing of Ovarian Tumours. Springer: Berlin.

Zweemer RP, Ryan A, Snijders AM, Hermsen MA, Meijer GA, Beller U, Menko FH, Jacobs IJ, Baak JP, Verheijen RH, Kenemans P, van Diest PJ (2001) Comparative genomic hybridization of microdissected familial ovarian carcinoma: two deleted regions on chromosome 15q not previously identified in sporadic ovarian carcinoma. Lab Invest 81: 1363–1370.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to María del Carmen González-Neira and Victoria Fernández (from the CNIO Human Cancer Genetics group) and to the CNIO Tumor Bank Network, in particular to María Jesús Artiga, for exceptional coordination of tumour collection and clinical data retrieval. We also thank the CNIO Histology and Immunohistochemistry Core Unit, especially Lydia Sánchez for excellent assistance. Also, we would like to acknowledge Paul P Eijk, Daniëlle Israeli, François Rustenburg, Dirk Vanessen and Jolanda Reek (VU University Medical Center, Department of Pathology, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for their technical and laboratory support. MJG is the recipient of a research contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio Español de Sanidad y Consumo (Miguel Servet Program, CP07/00113). MMK receives financial support from the Fundación La Caixa. This study was funded by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grants CP07/00113 and PS09/01094).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kamieniak, M., Muñoz-Repeto, I., Rico, D. et al. DNA copy number profiling reveals extensive genomic loss in hereditary BRCA1 and BRCA2 ovarian carcinomas. Br J Cancer 108, 1732–1742 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.141

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.141

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

BRCA locus-specific loss of heterozygosity in germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers

Nature Communications (2017)