Key Points

-

Explains the features of cracked tooth.

-

Describes diagnostic techniques and outlines treatment options.

-

Introduces a novel diagnostic and immediate management technique.

Abstract

Cracked tooth syndrome is a commonly encountered condition in dental practice which frequently causes diagnostic and management challenges. This paper provides an overview of the diagnosis of this condition and goes on to discuss current short and long-term management strategies applicable to dental practitioners. This paper also covers the diagnosis and management of this common condition and aims to inform clinicians of the current thinking, as well as to provide an overview of the techniques commonly used in managing cracked tooth syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cracks in teeth are exceedingly common. Some may be become problematic and can lead to symptoms, cracked tooth syndrome and tooth loss.

A 'crack' may be defined as a 'line on the surface of something along which it has split without breaking apart', while a 'fracture' may be considered to be 'the cracking or breaking of a hard object or material' (www.oxforddictionaries.com).1 Cracks on teeth may range from innocuous craze lines limited to the enamel layer, to a split tooth to one that may display the presence of a vertical root fracture. The term 'incomplete fracture' is used to describe a fracture plane of unknown depth and direction passing through tooth structure that may, if not already doing so, progress to communicate with the pulp or periodontal ligament'.2 Where the fracture plane may progress to the external surface of the tooth (either the clinical crown or root) or to the pulp chamber (culminating in apical periodontitis), a diagnosis of a complete fracture may apply. Complete and incomplete fractures may be subdivided into those that take a vertical or oblique direction.3

Incomplete fractures of posterior teeth are commonly (but not always) associated with the condition of cracked tooth syndrome, frequently abbreviated to CTS. Patients presenting with CTS often complain of symptoms of sharp pain on biting and thermal sensitivity particularly during the consumption of cold foods and beverages.4 The intensity of the perceived pain on biting is often proportional to the magnitude of the applied force.5 Additional symptoms that are less frequently reported include: the perception of pain on release particularly when fibrous foods are eaten, (a phenomenon termed 'rebound pain'), pain elicited by the act of tooth clenching or grinding or by consuming sugary substrates and less commonly by heat stimuli. Sometimes, patients suffering from CTS are also able to accurately locate the affected tooth. The precise cause of the symptoms associated with CTS is unknown.6,7

The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the condition of CTS as well as to appraise traditional management strategies including the description of a recently described technique to assist with the diagnosis, immediate management and subsequent treatment of CTS.

CTS

Epidemiology and aetiology

Cracked tooth syndrome appears to typically affect adult patients that are past their third decade, often affecting teeth that have previously received restorative intervention, although not exclusively.8 A possible reason includes older teeth having more restorations and may thus experience increased lateral occlusal load due to the possible loss of anterior guidance over time.

Mandibular molar teeth seem to be most commonly involved, followed by maxillary premolars, maxillary molars and mandibular premolars. In a recent clinical audit, mandibular first molar teeth were most commonly affected by CTS possibly due to the wedging effect of the opposing prominent maxillary mesio-palatal cusp onto the mandibular molar central fissure.9

The aetiology of CTS is multifactorial. Causative factors include: previous restorative procedures, occlusal factors, developmental conditions/anatomical considerations, trauma and miscellaneous factors (such as an ageing dentition with a concomitant reduction in physiological elasticity and or the presence of lingual tongue studs).10

Diagnosis of CTS

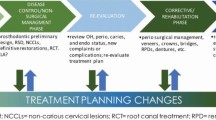

The diagnosis of CTS (Fig. 1) is often based on the reporting of a history of cold sensitivity and sharp pain on biting hard on fibrous food, with an alleviation of symptoms on the release of pressure. However, the perceived symptoms may display variation in accordance to depth and orientation of the crack.11 The visual detection of a crack, often aided with the use of a sharp explorer probe ideally with magnification, may help to confirm a suspected diagnosis; however, not all cracks are symptomatic. The application of point load testing devices to apply a force to a suspected fracture is risky, due to the possibility of fracture of the tooth, restoration or the opposing tooth and therefore the authors do not recommend their use.

Hypersensitivity to an applied cold stimulant (indicative of pulpal inflammation) may also help to confirm a diagnosis of CTS. Affected teeth are however seldom tender to percussion, by virtue of the absence of a complete fracture and the absence of irreversible pulpitis. The taking of radiographs to see a coronal crack can be of a limited diagnostic benefit, as cracks may run parallel to the plane of the film. The use of a light to transilluminate a tooth can be helpful. It has been suggested that yellow/orange lights may be of greater value than blue light. However, blue lights are more readily available. Figure 1 includes a flow diagram which may be used to assist with the diagnosis and management of CTS.

Consensus opinion would suggest that the presence of a history of symptoms as noted above, hypersensitivity to cold and a positive bite test are likely to indicate the presence of an incomplete tooth fracture. However, in the opinion of the authors it is common for a misdiagnosis to occur or indeed ambiguity to exist over a precise diagnosis, which may prove frustrating to all concerned, often necessitating specialist attention.12

The above is accounted for by there being several other conditions that may yield similar symptoms to those of CTS, including some commonly encountered conditions such as occlusal trauma, acute periodontal disease, dentine hypersensitivity, galvanic pain, post-operative hypersensitivity, fractured restorations, to less frequently diagnosed conditions such as trigeminal neuralgia and atypical facial pain.13 Establishment of an accurate diagnosis may also be compounded by the lack of sensitivity offered by the clinical tests described above and also by virtue of the presenting symptoms often displaying diversity and inconsistency (which may also relate to the exact depth and direction of the crack).9

The authors have recently described a useful; clinically quick and easy way to establish or confirm a diagnosis with the use of a 'trial' localised supportive composite splint.9 Here, the suspected tooth exhibiting CTS symptoms of pain upon release is isolated using cotton wool rolls. Resin composite is placed onto the dried occlusal surface of the suspected tooth without any etching or bond application to a thickness of 1.0 to 1.5 mm and wrapped across the external line angles of the tooth extending onto the (palatal/lingual and buccal) axial walls by 2-3 mm. No effort is made to contour the material. Once the material has been cured, the un-bonded resin overlay has the potential to serve as an occlusal splint. The patient is warned that the tooth will feel proud and then asked to bring this tooth into contact with its antagonist and asked to bite and slowly increase the pressure as a repeat of the initial 'bite' test. The absence of any pain upon release of the pressure may help to confirm a suspect diagnosis of CTS. An example of a trial splint is shown by Figure 2.

Management of CTS

A number of differing protocols have been described in the contemporary literature for the successful management of CTS.14 There is however, only limited data available documenting the relative merits and drawbacks of each. In the opinion of the authors, the selected protocol should offer an effective, efficient, economic, predictable and biologically conservative means of treating this condition.

While some advocate the removal of the affected cusp, followed by restoration of the residual defect or subtractive occlusal adjustments,15 the consensus approach for the management of incompletely fractured posterior teeth would generally appear to involve the immobilisation or splinting of the affected tooth, so as to prevent the independent movement of the fractured portions upon occlusal loading. Immobilisation in this manner may also prevent further progression of the fracture plane.16,17

Where removal of the fractured cusp is to be undertaken, it should be performed with extreme caution, as there is a risk of attenuation of the fracture plane. Subtractive occlusal adjustment is invasive and will not help to avoid the continual flexure of the tooth upon loading when an occlusal load is applied.8 Cusp reduction to overlay it with a protective restorative material may be required: composite 2 mm, gold and other alloys 1 mm.

It is also important to check the anterior guidance when providing care. If necessary, thought may be given to the 'building up' of any worn anterior teeth to increase the level of disclusion.

Immediate management of CTS

Traditionally, unless the affected cusp has been splintered off during the removal of an existing restoration when undertaking exploratory procedure, acute management has generally been provided using immediate extra-coronal circumferential splints (such as copper rings, orthodontic bands or provisional crowns)18,19 or by the application of direct (intra-coronal or extra-coronal splints) usually involving some form of tooth preparation, where some biological compromise is likely to be incurred.20,21 Table 1 provides a summary of the traditional protocols used for the immediate management of CTS.

Direct intra-coronal restorations

When using an intra-coronal restoration to treat an incompletely fractured posterior tooth, the objective is to anchor the chosen dental material to the cavity walls at either side of the fracture plane. This would help to not only prevent the independent movement of the portions either side of the fracture plane, but also aid in restoring the intrinsic fracture toughness of a tooth.

The use of adhesively retained silver amalgam restorations has been described for the successful management of CTS.22 However, the evidence is very limited.

There is some evidence to support the short-term prescription of direct, resin bonded posterior composite restorations to treat cases of CTS.23 Opdam et al. evaluated the efficacy of direct composite intracoronal resin restorations (to treat painful, cracked posterior teeth where there were pre-existing silver amalgam restorations). Cases were followed up for a period of seven years; an annual failure rate of 6% was reported. This compared less favourably to where a second sample had received directly bonded resin overlay restorations. It was suggested that the inferior success of the intracoronal approach might relate to the progressive breakdown of the adhesive interface (between the tooth and restoration) with cyclical functional loading. The latter would thereby hamper the longer-term ability of the restoration to effectively splint the crack. This may be of particular concern among patients who may display a tendency towards parafunctional tooth clenching and grinding habits. Cuspal contraction that may also occur as a consequence of polymerisation shrinkage when placing composite resin restorations may have the unwanted effect of causing further propagation of the fracture.

Two clinical studies have shown that the use of a flexible polymer resin such as in SDR Bulk Fill (Dentsply) can reduce contraction stresses as well as increase the risk of cusp fracture, which may prove to be of future merit.24,25

The longer term management of CTS

It has been suggested that the placement of a restoration that provides cuspal coverage has the potential to restore the fracture toughness of a restored tooth to that of an intact tooth.26 In the case of a posterior tooth with a crack that has extended into dentine, it is reasonable to assume that the fracture toughness of the affected tooth is likely to be undermined. For this reason, it would seem prudent to restore such a tooth by the means of a restoration that provides cuspal protection and limiting cuspal flexure. This may be achieved by an onlay, overlay or crown restoration. Restorations that provide cuspal coverage may be fabricated directly or indirectly.

The use of direct onlay restorations to treat CTS

The use of direct materials to provide longer-term management of CTS has a number of clear merits; Table 2 has summarised these.

Direct onlays used to treat incompletely fractured posterior teeth may be formed using silver amalgam27 or resin composite.23 With the availability of adhesively retained materials, direct silver amalgam overlays are rarely provided in general dental practice.

Opdam et al. have reported very favourable longer-term success for the use of direct resin onlays for the management of incomplete posterior tooth fractures. The direct composite onlay restoration therefore offers a lesser invasive and aesthetic alternative to use of dental amalgam overlays for this purpose.23 It is likely that a reduction in the height of the affected cusp will reduce the leverage placed on it when an occlusal load is applied, while its coverage with a plastic material will not only provide a form of 'shock absorption' but also help to divert occlusal loads from the crack towards the axial walls (to which the overlay will be anchored) and ultimately down the long axis of the tooth (which may in turn also lessen the stresses applied to the adhesive interface) and optimise restoration longevity.

Indirect restorations with cuspal coverage

Indirect techniques offer the use of dental materials which have the potential to offer superior mechanical properties in the oral environment, and are perhaps less demanding of operator skill versus the use and placement of direct onlay restorations.14 When using occlusal coverage restorations, the cusp angle should be reduced to reduce the risk of lateral loading.

Channa et al.28 have reported the successful application of resin bonded alumina abraded Type III cast gold alloy onlays for the management of CTS over a mean service period of 4.0 years. However, a relatively small sample of cases were included. The latter restorations have the potential to offer superior marginal adaptation and finish, favourable wear characteristics and a high level of corrosion resistance.

The use of ceramic onlays to treat CTS should perhaps be undertaken with an element of caution. Ceramics are relatively brittle materials that display limited ability of plastic deformation under load. The presence of a lower elastic modulus in comparison to resin composite based materials culminates in a superior ability of resin composites to absorb compressive loads by 57% versus that displayed by dental porcelains.29 Thus, ceramics are less likely to offer desirable 'shock absorbing' properties, with the possibility of an incomplete alleviation of symptoms as well as the risks of continued fracture propagation. Furthermore, intra-oral adjustments with dental ceramic materials may be challenging. There is, however, very limited data to support (or indeed contraindicate) the use of ceramic onlays to treat CTS.14 Given the current lack of any substantive evidence to contraindicate the application of ceramic based materials for the management of CTS, it would perhaps be appropriate to not completely discount their application for the treatment of cracked teeth based simply on the findings of this laboratory study alone as the evidence is not conclusive. Further evidence is clearly required.

Indirect composite onlays may provide an aesthetic alternative to the use of ceramic, with the merits of ease of adjustment, and repair (which may be relevant if subsequent endodontic treatments are required). A retrospective study by Signore et al. has reported very promising results for the use of bonded indirect resin onlays for the treatment of cracked, painful posterior teeth. A survival rate of 93% over a period of six years among a sample of 43 teeth was determined.5

Indirect adhesive onlay techniques offer a more conservative alternative to full coverage restorations. However, there still exists the need for subtractive tooth preparations if restorations are to conform to the existing occlusal scheme. The use of in-surgery CAD/CAM manufacturing techniques may however, offer some potential by overcoming difficulties such as the challenges associated with provisionalisation which may increase the risks of pulpal complications among incompletely fractured teeth.16

The prescription of full coverage crowns has been suggested to be the most suitable form of treatment for the management of CTS.32 This is based on the potential ability of the resistance form provided by such restorations to help dissipate applied occlusal loads over the entire prepared tooth as well as the retention form (by frictional contact) to provide effectual immobilisation. Indeed, a bespoke preparation design has been advocated for cracked teeth including an additional level of reduction of the affected cusp.30

Full coverage crowns do not however offer a biologically conservative, time efficient and cost effective approach to the management of CTS. Indeed, endodontic complications have been documented as a significant concern when adopting this protocol with approximately one-fifth of a sample of 127 teeth affected by CTS requiring subsequent root canal treatment within the first six months of placement.31 The risks of irreversible pulp trauma appear to be exacerbated among teeth displaying an involvement of one of both of the marginal ridges; furthermore, the prognosis of cracked, root filled teeth has been reported to be poor, Tan et al.32

Teeth with symptomatic, incomplete fractures are likely to display a form of reversible pulpitis. It is likely that the further trauma of subtractive preparations (to receive overlay restorations) coupled with the use of provisional restorations, pulp tissue trauma sustained during restoration try-in (which may also involve further tooth desiccation) and cementation will further increase the 'stresses' placed on the already inflamed and irritated tissues. This in turn, will most likely further curtail the efficacy and predictability of indirect restorations to treat teeth affected by CTS (especially where more invasive preparation designs are applied).

A novel ultra-conservative approach to the management of CTS (Fig. 3)

As an extension to the placement of a supra-coronal trial, directly non-bonded direct resin overlay (applied without any tooth preparation) to further help establish a diagnosis for CTS as described above, Banerji, Mehta, Millar et al. have reported the successful placement of bonded, direct supra-coronal resin onlay restorations (DCS) for the treatment of incompletely fractured teeth by the means of a multi-centreed retrospective audit, with an overall 86.7% success rate within three months of placement.9

The principles of this approach are based on those of well documented concepts of 'relative axial movement', which is commonly utilised to treat patients with pathological tooth wear by minimal intervention.33,34,35,36

Supraocclusal restorations should be contoured to be flat so as to limit lateral loading. iven that definitive restorations have occlusal contour, the use of a restoration with this form of anatomical design is not ideal for this purpose (although they have been shown to be otherwise effective), Gerasimidou et al.37 In each case, a careful assessment of placing a restoration in supra-occlusion was carried out, noting the eruptive potential of the patient, the risks of placing a supra-coronal restoration of the patient's oral health and informed consent was gained. Factors which may suggest the presence of a reduced eruptive potential include: the presence of an open bite, dental implants, fixed bridgework (with an abutment either side of the space), bony ankyloses, severe Class III malocclusions and the presence of prominent bony exostoses. Conditions which may also preclude the prescription of a supra-coronal restorations include: active periodontal disease, TMJPDS, prior orthodontic treatment, a heavily restored tooth (for instance a root filled tooth) or where the antagonistic tooth may be vulnerable to fracture.

However, intracoronal restorations should never be placed in supraocclusion as they are likely to increase pulpal pain and may cause cusp fracture. Intentionally high restorations must have full occlusal coverage, free of endodontic pathology (including root canal fillings), no pathology present, with patient understanding and consent.

The clinical steps involved for this technique include (Figs 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) and a flow diagram is also provided (Fig. 3):

-

Confirming the complete elimination of the symptoms of rebound pain from the diagnosed tooth with a non-bonded composite splint as described above

-

An evaluation of the periapical status and bone support with an accurate long cone periapical radiograph

-

An explanation of the technique should be provided to the patient, outlining the nature of the treatment along with instructions for anticipating the change in their occlusal scheme

-

The application of a slurry of pumice the occlusal and axial walls of the diagnosed tooth, or the alternative use of air-abrasion techniques

-

Conditioning for adhesive bonding using a total etch technique, involving the use of 37% phosphoric applied over the occlusal and the axial walls for 20 seconds, followed by thoroughly washing the surfaces and the subsequent drying of the etched surfaces

-

Placement and curing of the chosen bonding resin as per the manufacturers' instructions

-

Placement of a composite resin on the occlusal surface and 2–3 mm down the axial walls (buccal, palatal/lingual). The depth of composite resin placed on the occlusal surface should be to 1.0–1.5 mm in thickness, along the axial walls composite to finish in an infinity bevel and supragingivally. Light cure to manufacturers' instructions

-

The occlusal surface should to remain 'flat' with the absence of any contact during any excursive mandibular movements. In certain instances a canine rise may be added in composite to achieve this

-

Composite to be polished

-

The patient should be reviewed within in one week to confirm alleviation of symptoms, followed by a periodic review every two weeks until all other tooth contacts are re-established

-

Substitution of the composite splint with a definitive adhesive restoration once other tooth contacts reestablished. Remove canine rise restoration if required.

Following confirmation of the alleviation of symptoms with a 'trial' splint (as shown in Fig. 3) a bonded direct composite splint (DCS) is placed on the lower right second molar tooth

The occlusion has been re-established after a period of three months following DCS placement for case shown in Figure 10

The DCS has been replaced with a Type III cast adhesive gold onlay for the case shown in Figure 10

While further work is needed to fully support this approach, the use of a DCS restoration has the potential (where careful case selection is applied) to provide a conservative, effective, predictable, efficient and economical approach to the short to medium term management of CTS. It may be particularly appropriate where there may exist a doubt over the exact diagnosis. An extrapolation of this approach may involve the placement of indirect adhesive onlays in supra-occlusion as a means for the long-term management of incompletely fractured teeth in an ultra-conservative manner, where there is little doubt over the diagnosis.

With the advancement of CAD-CAM technology the fabrication of the proposed onlay can now be produced at the chairside once the diagnosis has been established.

Conclusion

The diagnosis and management of CTS in dental practice can sometimes prove to be highly taxing on the operator. There is a need for an effective technique to provide immobilisation. The DCS restoration may have considerable merits for the diagnosis and management of CTS in a predictable and minimally invasive manner. However, there is a need for further research into this technique as well as into alternative forms of management as discussed above, in order to support (or indeed contraindicate) the notion of any one approach (inclusive of a given dental material and or restoration form) being superior to another.

References

Crack – definition of crack in English from the Oxford dictionary. Available at: www.oxforddictionaries.com (accessed April 2017).

Ellis S G . Incomplete tooth fracture-proposal for a new definition. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 424–428.

Silvestri A, Singh I . Treatment rationale of fractured posterior teeth. J Am Dent Assoc 1978; 97: 806–810.

Cameron C E . The cracked tooth syndrome: additional findings. J Am Dent Assoc 1976; 93: 971–975.

Signore A, Benedicenti S, Covani U . Ravera G. A 4 to 6 year retrospective clinical study of cracked teeth restored with bonded indirect resin composite onlays. Int J Prosthodont 2007; 20: 609–616.

Davis R, Overton J . Efficacy of bonded and non-bonded amalgams in the treatment of teeth with incomplete fractures. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131: 496–478.

Dewberry J A . Vertical fractures of posterior teeth, Lieve F S (ed). Endodontic therapy, 5th edition. pp 71–81. St Louis: Mosby, 1996.

Hiatt W H . Incomplete crown-root fractures in pulpal periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1973; 44: 369–379.

Banerji S, Mehta S B, Kamran T, Kalakonda M, Millar B J . A multicentered clinical audit to describe the efficacy of direct supra-coronal splinting – a minimally invasive approach to the management of cracked tooth syndrome. J Dent 2014; 42: 862–871.

Lynch C, McConnel R . The cracked tooth syndrome. J Can Dent Assoc 2002; 68: 470–475.

Geurtsen W, Schwarze T, Gunay H . Diagnosis, therapy and prevention of the cracked tooth syndrome. Quintessence Int 2003; 34: 409–417.

Banerji S, Mehta S B, Millar B J . Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 1 : aetiology and diagnosis. Br Dent J 2010; 208: 459–463.

Turp C, Gobetti J . The cracked tooth syndrome: an elusive diagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc 1996; 127: 1502–1507.

Banerji S, Mehta S B, Millar B J . Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 2 : restorative options for the management of cracked tooth syndrome. Br Dent J 2010; 208: 503–514.

Agar J R, Weller R N . Occlusal adjustments for initial treatment and prevention of cracked tooth syndrome. J Prosthet Dent 1988; 60: 145–147.

Griffin J . Efficient, conservative treatment of symptomatic cracked teeth. Compendium 2006; 27: 93–102.

Liebenberg W H . Partial coverage indirect tooth coloured restorations; steps to clinical success. Am J Dent 1999; 12: 201–209.

Ehrmann E H, Tyas M J . Cracked tooth syndrome: diagnosis, treatment and correlation between symptoms and post-extraction findings. Aust Dent J 1990; 35: 105–112.

Gutherie G C, Difiore P M . Treating the cracked tooth with a full crown. J Am Dent Assoc 1991; 122: 71–73.

Saunders W P, Saunders E M . Prevalence of periradicular periodontitis associated with crowned teeth in an adult Scottish subpopulation. Br Dent J 1988; 185: 137–140.

Cheung G S, Lia S C, Ng R P . Fate of vital pulps beneath a metal ceramic crown or a bridge retainer. Int Endod J 2005; 38: 521–530.

Bearn D, Saunders E, Saunders W . The bonded amalgam restoration – a review of the literature and report of its use in the treatment of four cases of cracked tooth syndrome. Quintessence Int 1994; 25: 321–326.

Opdam N J, Roeters J J, Loomans R A, Bronkhorst E . Seven year clinical evaluation of painful, cracked teeth restored with a direct composite restoration. J Endod 2008; 34: 808–811.

van Dijken J W V, Pallesen U . A randomized controlled three year evaluation of 'bulk-filled' posterior resin restorations based on stress decreasing resin technology. Dent Mater 2014 30: e245–e251.

McGuirk C, Hussain F, Millar B J . The effect of a bulk-fill base on the clinical survival of direct posterior composite restorations. Eur J Prosthod Rest Dent 2017 - in press

Hodd J A A . Biomechanics of the intact, prepared and restored tooth; some clinical implications. Int Dent J 1991; 41: 25–32.

Davis R, Overton J . Efficacy of bonded and non-bonded amalgams in the treatment of teeth with incomplete fractures. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131: 496–478.

Chana H, Kelleher M, Briggs P, Hopper R . Clinical evaluation of resin bonded gold alloys. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 83: 294–300.

Brunton P A, Cattell P, Burke F J T, Wilson N H F . Fracture resistance of teeth restored with onlays of three contemporary tooth-coloured resinbonded restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 82: 167–171.

Casciari B J . Altered preparation design for cracked teeth. J Am Dent Assoc 1991; 130: 571–572.

Krell K, Rivera E . A six year evaluation of cracked teeth diagnosed with reversible pulptitis; treatment and prognosis. J Endod 2007; 33: 1405–1407.

Tan I, Chen N N, Poon C Y, Wong H B . Survival of root filled cracked teeth in a tertiary institution. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 886–889.

Dahl B, Krungstad O, Karlsen K, An alternative treatment of cases with advanced localised attrition. J Oral Rehab 1975; 2: 209–214.

Dahl B, Krungstad O . Long term observations of an increased occlusal face height obtained by a combined orthodontic/prosthetic approach. J Oral Rehabil 1985; 12: 173–170.

Poyser N, Porter R, Briggs P, Chana H, Kelleher M . The Dahl concept: past, present and future. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 669–676.

Hemmings K, Darbar U, Vaughn S . Tooth wear treated with direct composite at an increased vertical dimension: results at 30 months. J Prosthet Dent 2000; 83: 287–293.

Gerasimidou O, Watson T, Millar B J . Effect of placing intentionally high restorations: randomized clinical trial. J Dent 2016; 45: 26–31.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Banerji, S., Mehta, S. & Millar, B. The management of cracked tooth syndrome in dental practice. Br Dent J 222, 659–666 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.398

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.398

This article is cited by

-

Cracked Tooth Syndrome and Strategies for Restoring

Current Oral Health Reports (2023)

-

A perspective on the diagnosis of cracked tooth: imaging modalities evolve to AI-based analysis

BioMedical Engineering OnLine (2022)