Key Points

-

Highlights the greater impact of dental decay on children from more deprived backgrounds.

-

Reports that the cost of DGAs in Southampton in 2014-15 was around £210,000.

-

Suggests that DGA data must be interpreted with caution as changes in numbers could be the result of service issues and changes, and not dental decay levels.

-

Suggests these data could be used to benchmark dental decay levels in children, evaluate the impact of local oral health improvement interventions, and advocate for investment.

Abstract

Aim To explore the value of DGA data as an indicator of the impact and inequalities associated with child dental decay (caries) in Southampton.

Design Data from the local DGA provider in Southampton was used to investigate trends in child (17 years and under) DGAs between 2006/7 and 2014/15. Retrospective analysis of anonymised child-level 2013/14 and 2014/15 data from the same service was carried out to identify any inequalities with respect to deprivation, impact on school attendance and cost to the health economy.

Results Around 400-500 Southampton children needed a DGA annually within this period. There were year-on-year variations, but no upward or downward trend. The DGA rate was 2.5 to three times higher in the most deprived quintile compared to the least. This translates to an equivalent gap in school absences, which could impact on educational achievement. The cost of these procedures in 2014/15 was around £210,000.

Conclusions DGA data have value in highlighting the impact and inequalities associated with dental decay on children and the wider economy. Nationally, they could be used for benchmarking. Locally, these data could be used to target and evaluate health improvement programmes as well as to highlight DGA service changes that would disproportionately affect children from more deprived backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dental decay (caries) levels in the UK have declined over the last few decades but inequalities remain.1 The consequences of dental decay include toothache, infection and tooth loss which can affect eating and speech development as well as significant cost implications.2,3 Treating dental disease costs the NHS in England £3.4 billion per year.4

Local authorities are responsible for oral health surveillance to inform the local commissioning of dental services.5 Oral health surveillance relies largely on nationally-coordinated surveys which started in the 1980s and assesses numbers of decayed, missing and filled teeth (dmft) to derive an indication of dental decay experience.6 A change in the regulations from negative (opt-out) to positive (opt-in) consent in 2006 resulted in falling participation levels with concurrent drops in reported dental decay levels.7 Evidence indicates that children with dental decay are less likely to participate, so the data may be depicting a more positive picture than may be the case in reality.8,9

There is a known link between deprivation and poor oral health, but published research indicates that deprivation explains only part of the variation in dental decay across communities with figures quoted ranging from 44% to 60%.10,11 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance states that assessing oral health need is 'hampered by the lack of available evidence on the impacts of poor oral health... with most of the evidence based on counting cavities in teeth, rather than measuring quality of life outcomes such as pain and the ability to eat'.12 The 2013 decennial Child Dental Health Surveys included questionnaires, capturing useful information about the impact of poor oral health on children and families.13 Additional indicators about the impact of poor oral health are needed to help local commissioners target and evaluate oral health services, particularly with regard to reducing inequalities.14,15,16

The Southampton public health team has, for many years, monitored DGAs as a measure of the impact of poor oral health in children. DGAs are carried out in hospital for children unable to cooperate with care under local anaesthesia.17 Nationally, removal of teeth due to dental decay is the most frequent reason for hospital admissions in children under five years of age, with the rate in the most deprived decile almost five times that in the least deprived decile.18,19,20 The consequences of this include parents having to take time off work to accompany their children at appointments and to care for them.

Southampton DGA data were obtained from the local provider and ongoing work resulted in the availability of a child-level dataset for 2013-14 and 2014-15. This paper aims to explore the potential value of DGA data for assessing the impact and inequalities associated with child dental decay.

The objectives are to:

-

Monitor trends in DGAs between 2006-7 and 2014-15

-

Investigate any association between DGA and deprivation

-

Extrapolate the potential impact of DGAs on school attendance

-

Assess the cost of DGAs to the local health economy.

Methods

The Southampton DGA service is commissioned by NHS England from a local community dental service (CDS) provider. Referrals are assessed by a dentist in a CDS clinic. Children who are deemed suitable for management under a local anaesthetic are returned to the referrer and suitable patients are redirected for care under sedation. Those needing a DGA are scheduled for the next available session. The sessions are carried out in a local hospital operating theatre with the GA provided by a specialist anaesthetist. A post-op appointment is scheduled at the CDS clinic. No restorative care is provided at these sessions.

Numbers of children undergoing DGAs were available from 2006/7 to 2014/15. Rates were calculated using the Hampshire County Council Small Area Population Forecasts.21 Further details for children with a valid postcode within Southampton (including postcode, date of birth, date of procedure and number of teeth extracted) who underwent DGA between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2015 were drawn from the CDS database. There is a possibility that a few children may have had more than one DGA over the two-year period but the data did not include unique identifiers, so we were unable to identify these. Our experience is that this does not happen often, but would result in a doubling of the impact on the child and resources used.

The data were collated in an Excel spreadsheet and analysed using descriptive statistics including calculating means with confidence intervals. The date of birth and date of procedure were used to calculate the age of the child at the time of the DGA. The child's postcode was used to determine ward of residence and deprivation quintile, using the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010.22 The statistical significance of differences in mean rates between years, age groups and deprivation quintiles was assessed using 95% confidence intervals.

Results

DGA rates varied from year to year between 2006/7 and 2014/15, highest in 2011-12 at around 12 per 1,000 children (515 children) and lowest in 2013-14 at 8.0 per 1,000 (396 children) (Fig. 1). Some of the variations were statistically significant, but there was no overall upward or downward trend. More detailed analysis of the change between 2013/14 and 2014/15 indicated an overall increase across all the three age-groups in that single time period (Fig. 2).

There were 1,677 teeth extracted from Southampton children aged 0-17 in 2013/14 and 2,248 in 2014/15. The mean number of teeth extracted was highest among children aged 0-5 years (Fig. 3).

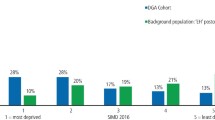

The rate of DGAs in the lowest deprivation quintile was three times that of the highest in 2013/14 and 2.5 times higher in 2014/15 (Fig. 4). The mean number of teeth extracted per child was just over four in both the most and least deprived quintiles in both areas, indicating similar levels of disease severity.

Each DGA for school-aged children (6-17 year-olds) was estimated to result in five missed schooldays (a day for the initial dental visit, a day for the GA pre-assessment clinic, a day for the DGA, a day for recovery on the following day and a day for the post-DGA assessment visit). In reality there may be more schooldays missed for toothache and recovery.

Using this estimate, DGAs accounted for around 1,510 missed schooldays in 2014-15. Figure 5 shows a three-fold difference with 500 missed schooldays in children from the most deprived quintile compared to 165 in the least deprived quintile.

Using the cost of £427 for a DGA procedure, the cost of this service in 2014-15 was £210,511.23 This does not include the economic cost of parents or carers taking time off work to manage appointments and care for their children, or the impact on other children in the household.

Discussion

These data highlight a number of issues relating to the health of children. There is potentially a case for neglect if children are experiencing toothache and DGAs because they are not getting timely access to dental care.24 DGAs are known to cause distress to children and parents, with children reporting post-op symptoms a week later.25,26 These data could be shared with other health and social care workers to address and prevent dental neglect and any wider issues which require assessment and support.27

The data demonstrate a potential three-fold difference in missed schooldays between the children in the most and least deprived quintiles. Recent evidence indicates that increased absences may lead to lower achievement in Key Stage 2 examinations (aged 10-11 years). There was lower achievement in children with the highest five percent of absence rates (which would include absences due to dental issues) compared with those with the lowest five percent.28 This is not in line with the aspiration to give every child the best start in life.29 However, children across all deprivation quintiles are undergoing DGAs for dental decay, so interventions need to reach all children. The cost to the health economy is significant with over £200,000 spent in Southampton alone in 2014/15.

This information could be helpful for selecting, targeting and evaluating interventions.30 Areas with water fluoridation schemes have been shown to have lower DGAs when compared with areas which do not.31 Similarly, these data could be included in the evaluation of interventions such as supervised toothbrushing and parent education schemes, providing local information to direct local investment.

The data can also be used to monitor any changes in access to DGA care and identify opportunities for service improvement. For example, where there are increases in waiting times or location changes, these data can be used to highlight any disproportionately greater impact on children from more deprived backgrounds. They could also be used to highlight the need for more sedation services which may be suitable for some children requiring dental extractions.32 Sedation carries less risk and can be delivered in more accessible locations in primary care. Integrating preventive messages into the pathway could potentially reduce repeat DGAs in patients and benefit families.33 A recent publication identified possible improvements to their DGA pathway, including better assessment and discharge processes, which could reduce the need for first time DGAs as well as repeats.34

In 2016, the NHS Outcomes Framework (NHSOF) included, for the first time, 'Tooth extractions due to decay in children admitted as inpatients to hospital, aged 10 years and under' using data from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data. The data indicate a significant rise in the rate of tooth extractions due to dental decay in young children (aged ten years and under) admitted as inpatients to hospital from 445.7 per 100,000 population in 2011/12 to 462.2 in 2014/15. HES data may not currently capture all the DGA activity, which is delivered using different models across the country. Work is ongoing to improve the completeness of the data so they can be used more widely, including for benchmarking.35

There are some caveats with using DGA data. Changes in DGA rates may be due to service change, rather than changes in dental decay levels and changes in dental decay levels may not be reflected in the data if services are at capacity. Making these data comparable between areas and over time will require agreement on referral thresholds for DGAs, within the limits of individual clinical needs. There may be an opportunity here for national agreement on maximum waiting times for DGAs, to reduce variation due to service availability and facilitate timely access to care.

DGA rates only represent the severe end of dental decay in children. For a more complete picture, dental procedures carried out under local anaesthesia (LA) in dental surgeries would need to be included.36 There would also need to be an additional process to exclude dental extractions carried out as part of orthodontic treatments.

Finally, these data attract media and community interest, providing an advocacy opportunity for children's oral health. This may support the case for greater investment in oral health services and preventive interventions including water fluoridation.37

Conclusion

We have used simple analyses on locally-sourced data to demonstrate the potential value of DGA data in monitoring trends and inequalities at local level. If DGA data can be collected systematically across the country, the information can be routinely incorporated into national datasets, providing comparable information on the impact and inequalities in oral health. Locally, these data could be used to target and evaluate preventive strategies enabling investment to be directed to where it is most effective. The data could also be used to ensure that there is timely access to DGA care, promote the redirection of suitable cases to care under sedation and include oral health improvement messages. These data can be powerful in highlighting the impact of dental decay on children and the need for strategies to address this preventable condition.

References

Pillas D, Marmot M, Naicker K et al. Social inequalities in early childhood health and development: a European-wide systematic review. Pediatr Res 2014; 76: 418–424.

Clementino M A, Pinto-Sarmento T C A, Costa E M et al. Association between oral conditions and functional limitations in childhood. J Oral Rehabil 2015; 42: 420–429.

Broadbent J M, Thomson W M, Poulton R et al. trajectory of patterns of dental caries experience in the permanent dentition in the fourth decade of life. J Dent Res 2008; 87: 69–72.

NHS England. Improving dental care – a call to action. 2014. Available at: http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/impdentcare.pdf (accessed May 2017).

Statutory Instrument 2012 No 3094. National Health Service, England Social Care Fund, England Public Health, England. The NHS Bodies and Local Authorities (Partnership Arrangements, Care Trusts, Public Health and Local Health watch) Regulations 2012. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2012/3094/regulation/35/made (accessed May 2017).

Nugent Z I, Pitts N B . Patterns of change and results overview 1985/6 from the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry (BASCD) co-ordinated National Health Service surveys of caries prevalence. Community Dent Health 1997; 14: 30–54.

Public Health England. Dental public health epidemiology programme. oral health survey of 5-year-old children 2015. A report on the prevalence and severity of dental decay. May 2016.

Davies G M, Robinson M, Neville J et al. Investigation of bias related to non-return of consent for a dental epidemiological survey of caries among five-year-olds. Community Dent Health 2014 31: 21–16.

Dyer T A, Marshman Z, Merrick D et al. School-based epidemiological surveys and the impact of positive consent requirements. Br Dent J 2008; 205: 589–592.

Public Health England. National Dental Epidemiology Programme for England: oral health survey of five-year-old children. A report on the prevalence and severity of dental decay. London, 2013.

Broomhead T, Baker S R, Jones K et al. What are the most accurate predictors of caries in children aged 5 years in the UK? Community Dent Health 2014 Jun; 31: 111–116.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Oral health improvement for local authorities and partners. October 2014.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Children's Dental Health Survey England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2013. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB17137/CDHS2013-Executive-Summary.pdf.

Department of Health. Public health grants to local authorities: 2016-17.

Health and Social Care Act 2012 Chapter 7. Part 1 The health service: overview. Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/7/section/4.

NHS England. Five year forward view. October 2014.

Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for the management of children referred for tooth extractions under general anaesthesia. August 2011.

Health & Social Care Information Centre. NHS Outcomes Framework, England. February 2016: Quarterly publication.

Department of Health. Early Years High Impact Area 5 – Managing minor illness and reducing accidents (hospital attendance/admissions). Commissioning of public health services for children. 1 July 2014.

Royal College of Surgeons, Faculty of Dental Surgery. The state of children's oral health in England. January 2015.

Hampshire County Council. Small Area Population Forecasts. Available at: http://www3.hants.gov.uk/factsandfigures/population-statistics/pop-estimates/small-area-pop-stats.htm.

Department of Communities and Local Government. The English Indices of Deprivation 2010. March 2011.

NHS England. 2014-15 National Tariff Payment System. Annex 5a-National Prices.

Stevens C L . Is dental caries neglect? Br Dent J 2014 217: 499–500.

Gazal G, Mackie I C . Distress related to dental extraction for children under general anaesthesia and their parents. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2007; 8: 7–12.

Hosey M T, Macpherson L M, Adair P, Tochel C, Burnside G, Pine C . Dental anxiety, distress at induction and postoperative morbidity in children undergoing tooth extraction using general anaesthesia. Br Dent J 2007; 200: 39–43.

Jameson R . Working together to share the dental neglect. Br Dent J 2016 221: 755–756.

Department for Education. The link between absence and attainment at KS2 and KS4 2012–13 academic year. Research report, February 2015.

Public Health England. Who we are and what we do. Annual Plan 2015–16. July 2015.

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. June 2014.

Elmer T B, Langford J W, Morris A J . An alternative marker for the effectiveness of water fluoridation: hospital extraction rates for dental decay, a 2-region study. Br Dent J 2014; 216: E10.

Wanyonyi K L, White S, Gallagher J E . Conscious sedation: is the provision equitable? Analysis of sedation services provided within primary dental care in England, 2012–2014. BDJ Open 2016; 10.1038/bdjopen.2016.2.

Olley R C, Hosey M T, Renton T, Gallagher J . Why are children still having preventable extractions under general anaesthetic? A service evaluation of the views of parents of a high caries risk group. Br Dent J 2011 E13.

Raja A, Daly A, Harper R, Senghore N, White D, Raghavi V . Characteristics of children undergoing dental extractions under general anaesthesia in Wolverhampton: 2007–2012. Br Dent J 2016; 220: 407–411.

Department of Health. Refreshing the NHS Outcomes Framework: 2015–2016. Technical Appendix. August 2014.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. NHS Dental Statistics for England-2014/15.

BBC News. Child tooth removal 'at crisis point', doctors warn. 12 July 2015. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-33498324.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mortimore, A., Wilkinson, R. & John, J. Exploring the potential value of using data on dental extractions under general anaesthesia (DGA) to monitor the impact of dental decay in children. Br Dent J 222, 778–781 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.455

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.455

This article is cited by

-

Childhood caries and hospital admissions in England: a reflection on preventive strategies

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Service evaluation of the paediatric dental general anaesthesia service in NHS Lothian

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Co-design of an oral health promotion animated film with families in the South of England

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

A rapid review of variation in the use of dental general anaesthetics in children

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Frequency, variation and cost of dental extractions for adults in secondary care in Great Britain

British Dental Journal (2019)