Key Points

-

Highlights that a clear public dental health issue has been reinforced through the relatively high level of dental GA activity reported.

-

Suggests that a better assessment and discharge process may help reduce the need for first time DGAs, as well as repeats.

Abstract

Introduction Studying characteristics of children requiring extractions under dental general anaesthesia (DGA) can help identify trends, which can be used to facilitate future planning of healthcare services.

Objective To report on the profile of children who underwent extractions under DGA between 2007 and 2012 at the New Cross Hospital in Wolverhampton, England.

Methods Retrospective analyses of hospital records.

Results Of the 2692 patients seen between 2007 and 2012, 49.6% were boys and 50.4% were girls. The mean age was 7.1 and 7 to 12 years was the largest age group (43%). The majority of the sample was White British (67%). Of the 8,286 teeth extracted, 85% were primary teeth and 15% permanent. More teeth were extracted in boys than girls (P = 0.002) and 'Other' ethnicities had a higher mean number of extractions compared to White British (P <0.001) and South Asians (P = 0.046). The mean age of the patients has decreased over the years (P = 0.001) and the mean number of primary teeth extracted has increased (P = 0.001).

Conclusions A clear dental public health issue has been reinforced through the relatively high level of DGA activity reported. Though rigorous caries prevention remains the ultimate goal, a better assessment and discharge process may help reduce the need for first time DGAs as well as repeats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental general anaesthesia is primarily used for paediatric exodontia in young children. In the past, DGAs in the UK were performed in dental practices. However, the provision of DGA has been subject to gradual changes in recent decades, which eventually led to restricting such treatments to a hospital setting. In 1990, the Poswillo Report suggested that DGA 'should be avoided wherever possible' and emphasised a preference for sedation.1 In 1999, the Royal College of Anaesthetists highlighted the importance of appropriate training for administering DGA2 and in 2000, the Department of Health report 'A conscious decision' also recommended that DGA should be undertaken only when absolutely necessary.3 Following the publication of this report, the provision of DGA has been limited to a hospital setting where critical care facilities are available. Further guidelines on the organisation of DGA were published in 20084 and 2011.5

In spite of significant improvements in the oral health of the UK population in the past few decades, there remains a high prevalence of dental caries in children. The 2013 Children's Dental Health Survey6 found that nearly a third (31%) of 5-year-olds and half (46%) of 8-year-olds in England, Wales and Northern Ireland had obvious decay experience in their primary teeth.6 Although dental caries is preventable, it is the most common reason for tooth extractions among children.7 Analysis of hospital admissions in England suggested a considerable rise in the number of children admitted to hospital for dental problems and most of the increased admission was attributable to an increase in extractions for caries.8

Several aspects of the DGA experience have been examined, including studies on repeat DGAs,7,9 referral pathways10,11 and preventive strategies.12 Some have also reported on the demographic profile of children attending for DGA, considering factors such as age, sex, ethnicity and socio-economic background.7,13,14,15 These are very relevant in view of the fact that such variables are known to be associated with caries experience and treatment received6,16and studies on the characteristics of children requiring DGA can help identify trends, which can then be used to facilitate future planning of healthcare provision and target oral health promotion.15,17

This study aims to describe the profile of children who underwent DGA extractions between 2007 and 2012 at the New Cross Hospital in Wolverhampton, England. Data from patient records were analysed to report on the age, sex and ethnicity of the children as well as, the number of primary and permanent teeth extracted. Differences in these characteristics during the six year study period were also investigated.

Method

This is a retrospective study of hospital records. Data were drawn from records of children aged 16 years or younger who underwent DGA extractions between 2007 and 2012 at the New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton.

The DGA service at New Cross Hospital is managed by the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust and is staffed by the Special Care Dental Service (SCDS), a hospital consultant anaesthetist, theatre staff and paediatric nurses. The treatment was limited to extractions only and most of the referrals were from general dental practices (GDPs). On receipt of referrals, a pre-assessment (triage) was performed by a senior community dental nurse: the medical history was recorded and if appropriate, the child was placed on the DGA waiting list. No clinical examination was carried out, but any concerns about the suitability of the child for a GA were discussed with the operating dentist or hospital anaesthetist. At the DGA appointment, the child was assessed by the operating dentist (RH): the medical history was re-checked, dental examination completed (including radiographs if appropriate) and consent obtained.

Two SCDS dentists (RH, NS) extracted data from hospital records and entered this on to a spreadsheet. Research and development approval was obtained. Data was extracted from the anaesthetic register and included the child's age, sex, type and number of teeth extracted. Ethnicity data was collected from patient files. Questions relating to ethnicity detailed the ethnic background of the children in fourteen categories. For the purpose of data analyses, these categories were merged into three broad groups (White British, South Asian, Other ethnicities).

A total of 2,701 children aged 16 years or younger underwent DGA extractions between 2007 and 2012. Data was analysed for 2692 patients as nine were excluded due to incomplete records.

Basic descriptive statistics were presented and relevant graphs and tables produced. Testing for statistical significance was performed using χ2, t-test, ANOVA, and Tukey post hoc analyses wherever appropriate. Statistical significance was set at the P value of 0.05. Data analyses were performed using STATA 12.

Results

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic characteristics of the sample. Of the 2692 patients, 1,336 were boys (49.6%) and 1,356 were girls (50.4%). The mean age of children was 7.1. Children aged 7 to 12 years was the largest age group (43%). The majority of the sample was White British (67%); South Asians (Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi) accounted for 13% and the remainder were from 'Other' ethnic backgrounds (19%). Between 2007 and 2012, 8,286 teeth were extracted. Of those, 7,028 (85%) were primary teeth and 1258 (15%) were permanent teeth. Of the 2634 children that had data on the number of extracted teeth, 2,036 children had only primary teeth extracted (77.2%), 439 had only permanent teeth extracted (16.6%), and 159 children (6%) had both primary and permanent teeth extracted. For the sample as a whole, the mean number of teeth extracted was 3.14; the mean number of primary and permanent teeth extracted were 2.67 and 0.48, respectively. However, for children who had at least one primary tooth removed, the mean number of primary teeth extracted was 3.2 and among children that had at least one permanent tooth removed, the mean number of permanent teeth extracted was 2.1.

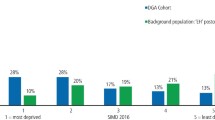

Table 2 and Figure 1 show the mean number of extracted teeth according to sex and ethnicity. There was a sex difference in the total number of extracted teeth with more teeth extracted in boys (mean = 3.28) than girls (mean = 3.01) and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.002). With regards to ethnicity, there were significant differences for the total sample (P <0.001). Post hoc Tukey analyses showed that 'Other' ethnicities had a higher mean number of extractions compared to White British (P <0.001) and South Asians (P = 0.046). A similar pattern was observed for 4- to 6-year-olds. Similar analyses were performed for primary and permanent teeth but they do not appear in the table (available upon request from corresponding author).

Table 3 shows changes in the mean number of extracted teeth and mean age between 2007 and 2012. Trend analyses were conducted to evaluate these changes over years. The positive values of z scores indicate the increasing pattern, whereas the negative values indicate the decreasing trend. During the six years studied, the mean number of extracted primary teeth has increased (P = 0.001) whereas the mean number of permanent teeth has decreased (P <0.001). The mean number of total extracted teeth does not show any statistically significant pattern (P = 0.646). Similar analyses showed that the mean age of the patients has decreased over the years (P = 0.001).

Visual evaluation of the mean number of extracted teeth between 2007 and 2012 (Fig. 2) showed a remarkable increase in 2012 for primary teeth and the total number of extracted teeth. ANOVA and Tukey post hoc analyses demonstrated that the mean number of extracted primary teeth in 2012 was significantly higher than all previous years. However, for the total number of extracted teeth, the mean in 2012 was only significantly higher compared to the previous two years.

Table 4 shows the percentage breakdown of children attending by ethnicity between 2007 and 2012. White British children consistently accounted for the highest proportion of the sample with the largest proportion recorded in 2010 (70.2%) and the smallest in 2012 (55.6%). The second largest ethnicity in these years was children of Indian origin, which formed 7% to 9% of the sample.

Discussion

This study set out to describe the profile of children attending for DGA at the New Cross Hospital in Wolverhampton from 2007 to 2012. Dentists at New Cross had concerns about an apparent increase in the number of young children requiring DGA and when they embarked on collecting data, this was from a purely clinical perspective rather than academic. As a result of this, some limitations have been identified, which will be discussed in due course. However, the sample studied was sizeable compared to some earlier studies7,18and analyses have identified useful and interesting changes in the profile of children that attended during the six years under investigation.

Within this period, 2692 children underwent extractions under DGA. There was no sex difference with regards to attendance but more teeth were extracted in boys than girls. This sex distribution was similar to that identified in previous studies15,18and also confirms the wealth of literature showing poorer oral health among boys.6

The mean age of the children was 7.1, which is similar to that reported by others7,15 and the age of children attending for DGA appears to be decreasing over the years. This too supports the findings from other centres.14,18The age ranges were categorised to complement the classification of age groups in the Department of Health's 'Toolkit for Prevention'.19 Forty-three percent of children fell within the 7 to 12 year age group suggesting they might benefit from fissure sealants on permanent molars.20

Of the 8,286 teeth extracted, 15% (1,258) were permanent teeth. Data on the reasons for extraction was not available so there is a possibility some of these might be orthodontic extractions, although dental caries remains the most common reason for extractions in children.6,8Irrespective of this, older children requiring only one or two permanent tooth extractions may have been able to have these performed using sedation. A Cochrane review on the use of sedation versus GA for provision of dental treatment in patients under 18 years could not find any randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the two techniques and so was unable to make any recommendations as to the safety, efficiency or cost-effectiveness of these two interventions.21 In spite of this, various studies have shown that young patients experience less morbidity and psychological distress when opting for inhalation sedation (IHS) as opposed to a GA.22,23The SCDS in Wolverhampton did offer IHS as an alternative to GA, especially for older children. However, some parents refused this option (preferring to have all the extractions completed in one visit under a GA). Also, most had waited at least two to three months for the DGA and so were unwilling to wait any longer for a sedation appointment, especially if their child was in pain. During the period over which data was collected, the assessment procedure was such that the option of sedation was only discussed at the DGA visit, so it is hardly surprising that uptake was poor, as parents and children were attending this appointment already 'prepared' for the DGA. Since 2012, the assessment procedure has changed: patients now attend an assessment appointment before the DGA, which allows the alternatives (including IHS) to be discussed before booking patients in for a DGA. The impact (if any) of this change in practice in terms of uptake of sedation services remains to be seen but is certainly worth exploring, particularly in view of the fact that a better assessment process has been shown to favour the use of alternatives such as sedation, resulting in reduced DGAs for cooperative children, especially when only one or two teeth need extracting.13

Between 2007 and 2012, 7,028 primary teeth were extracted, suggesting the DGA service at New Cross clearly provides a crucial service for the community. Furthermore, during this period, the mean number of primary teeth extracted has increased, especially in 2012. This may be associated with increasing levels of dental disease, but could also reflect more aggressive treatment planning to avoid a repeat DGA.7,9 Some carious teeth may have been restorable dependant on the child's compliance to dental treatment and where appropriate, parents were offered restorations rather than extractions and this included treatment under IHS. However, as explained earlier, uptake was generally poor, and in any case, for many younger children, sedation is less likely to be a suitable alternative to GA, especially if they require multiple extractions.24 One further point to highlight here is that, the DGA at New Cross is limited to extractions only. Holt et al. suggest that pre-cooperative children should have greater opportunity for restorations rather than just extractions under DGA.13 There appears to be much variation in service commissioning across geographical areas in the UK, including the availability of restorative care under DGA,17 so it would be worthwhile to investigate the feasibility of developing this aspect of care at New Cross.

We unfortunately have little definitive information about the dental care these children received before the DGA referral, including the level of restorative care provided in the primary care sector. SCDS clinicians did however report that most of the referrals were from a relatively small number of GDPs, which were in some of the most socially deprived areas of the city, and the majority of children were irregular attenders, whose first visit with a GDP was often as an emergency. This could therefore suggest that high disease levels in the local population groups might be the major contributory factor for the larger number of referrals as opposed to any lack of restorative care. However, this aspect merits further investigation. It would be prudent to target resources to areas with the highest needs while ensuring that services are accessible and convenient for families to facilitate uptake.

The increasing number of extractions also highlights the continued importance of oral health promotion and prevention strategies to limit the need for DGA, as well as to avoid a repeat.15,20 Although data on the rate of repeat DGA for the complete cohort was not collected, a separate audit over the period 2010 to 2012, found that 3.2% (14 of the baseline 432 patients attending for DGA in 2010) returned for a repeat DGA within the next three years. Previous research suggests that a repeat DGA is often required to address new caries.7 In Wolverhampton, preventive advice was always offered at the pre-assessment visit and a small number of children were also re-booked following the DGA to carry out preventive treatments such as fluoride application and fissure sealants. However, the service lacks capacity to follow up all patients after the DGA so most children are simply discharged back to the referring dentist. It has been suggested that discharge letters may be a useful way to emphasise the issue of prevention25 and this is a measure worth exploring at New Cross. Certainly, the discharge process should encompass a programme for prevention and in this respect, closer collaboration with colleagues in primary care may help to ensure the continued needs of these high caries risk children are met.

Guidelines for the management of children referred for dental extractions under GA5 describe an evidence based care pathway for these patients and make recommendations on what this should include. Key points of particular relevance to this study are: for the assessment to be undertaken at a separate appointment to the DGA (unless there is an urgent clinical need); relevant radiographs to be available; alternative treatment options to be discussed at this visit to allow adequate time for consideration by parents; and for the assessment to ideally be carried out by a specialist in paediatric dentistry or a dentist with appropriate experience in paediatric dentistry. The implementation of a new assessment procedure at New Cross (since 2012), goes some way to achieving these goals and compares very favourably with systems that were in place during the study period. Most notably, children are now seen at a community dental clinic for an assessment before the DGA appointment; the assessment is carried out by a senior dental officer (NS) and includes a dental examination (with radiographs if appropriate) and alternative treatment options (including IHS) are discussed. Although the dentists carrying out the assessment (NS) or extractions (RH) are not specialists in paediatric dentistry, they are very experienced clinicians and have been undertaking the DGA activity for many years. Furthermore, if patients do warrant a specialist opinion, advice can be sought from colleagues at the Birmingham Dental Hospital and if necessary, they can be referred on.

Previous studies have shown significant associations between the need for extractions under DGA and the relative deprivation of a child's area of residence.8,18 Unfortunately, detailed post code data was not available, so the impact of socioeconomic level in this cohort of patients could not be investigated.

People from a wide range of ethnic backgrounds used the DGA services in this study. In every year, the largest numbers of children belonged to the White British group. The size of all ethnic groups appears to remain stable over the six years, with the exception of 'White Other' where there was a notable increase from 2007 to 2012. However, data analysis for individual ethnic groups is limited by the small size of each group so it cannot be said that this is a significant finding.

Ethnicity has been reported in previous studies,15 but findings are bound to vary based on the population studied so the value of comparisons is limited. It would be more important to determine if any changes in the ethnic profile of children requiring DGA represent differences in oral health and or treatment provided, or whether they simply reflect changing ethnic patterns in the community. An examination of demographic data for Wolverhampton26 suggests the trends identified in this sample might indeed reflect profile changes in the local population. However, children from 'Other' ethnicities did have a higher mean number of extractions compared to White British and South Asian children. This calls for more research on the breakdown of ethnicities and cultures to investigate reasons for any variation, and to tailor oral health input and preventive strategies accordingly.

Conclusion

This paper presents an interesting picture of the profile of children requiring DGA in Wolverhampton from 2007 to 2012. Previously identified knowledge has been confirmed in that the number of primary tooth extractions performed each year is increasing, and the patient group is becoming younger. Subtle changes in the ethnic mix of the patient base were found and a clear public dental health issue has been reinforced through the relatively high level of DGA activity reported. These findings are unlikely to be unique to this centre, suggesting a similar picture in other centres around the country.

Seeing patients for an assessment appointment before the DGA visit has the potential to improve uptake of sedation services, especially for older children requiring only one or two extractions; further research is required to measure the impact (if any) of changes to the assessment procedure at New Cross since 2012.

It is also important to investigate the reasons for the relatively high number of referrals from a small group of practices. Caries prevention remains the ultimate goal, but closer collaboration with local GDPs working in 'high risk' areas, including a better discharge process, may go some way towards reducing the need for first time DGAs, as well as repeats.

References

Poswillo D . General anaesthesia, sedation and resuscitation in dentistry. Report of an expert working party prepared for the Standing Dental Advisory Committee. London: Department of Health, 1990.

The Royal College of Anaesthetists. Standards and guidelines for general anaesthesia for dentistry. London, 1999.

Department of Health. A conscious decision: a review of the use of general anaesthesia and conscious sedation in primary dental care. Department of Health: London, 2000. Available online at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4019200.pdf (accessed August 2015).

Davies C, Harrison M, Roberts G . UK national clinical guidelines in paediatric dentistry: guideline for the use of general anaesthesia (GA) in paediatric dentistry. London: Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2008. Available online at http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/fds/publications-clinical-guidelines/clinical_guidelines/documents/Guideline%20for%20the%20use%20of%20GA%20in%20Paediatric%20Dentistry%20May%202008%20Final.pdf (accessed August 2015).

Adewale L, Morton N, Blayney M . Guidelines for the management of children referred for dental extractions under general anaesthesia. London: Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2011. Available online at http://www.apagbi.org.uk/sites/default/files/images/Main%20Dental%20Guidelines%5B1%5D_0.pdf (accessed August 2015).

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Children's Dental Health Survey; Executive Summary; England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2013. Available online at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB17137/CDHS2013-Executive-Summary.pdf (accessed August 2015).

Kakaounaki E, Tahmassebi J F, Fayle S A . Repeat general anaesthesia, a 6-year follow up. Int J Paediatr Dent 2011; 21: 126–131.

Moles D R, Ashley P . Hospital admissions for dental care in children: England 1997–2006. Br Dent J 2009; 206,.

Harrison M, Nutting L . Repeat general anaesthesia for paediatric dentistry. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 37–39.

Clayton M, Mackie I C . The development of referral guidelines for dentists referring children for extractions under general anaesthesia. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 561–565.

Tochel C, Hosey M T, Macpherson L, Pine C . Assessment of children before dental extractions under general anaesthesia in Scotland. Br Dent J 2004; 196: 629–633.

Karki A J, Thomas D R, Chestnutt I G . Why has oral health promotion and prevention failed children requiring general anaesthesia for dental extractions? Community Dent Health 2011; 28: 255–258.

Holt R D, Al Lamki S, Bedi R, Dowey J A, Gilthorpe M . Provision of dental general anaesthesia for extractions in child patients at two centres. Br Dent J 1999; 187: 498–501.

Grant S M B, Davidson L E, Livesey S . Trends in exodontia under general anaesthesia at a dental teaching hospital. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 347–352.

Olley R C, Hosey M T, Renton T, Gallagher J . Why are children still having preventable extractions under general anaesthetic? A service evaluation of the views of parents of a high caries risk group of children. Br Dent J 2011; 210: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.313.

Prendergast M J, Beal J F, Williams S A . The relationship between deprivation, ethnicity and dental health in 5-year-old children in Leeds UK. Community Dent Health 1997; 14: 18–21.

Robertson S, Chaollai A N, Dyer T A . What do we really know about UK paediatric dental general anaesthesia services? Br Dent J 2012; 212: 165–167.

Hosey M T, Bryce J, Harris P, McHugh S, Campbell C . The behaviour, social status and number of teeth extracted in children under general anaesthesia: A referral centre revisited. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 331–334.

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2014. Available online at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/delivering-better-oral-health-an-evidence-based-toolkit-for-prevention (accessed August 2015).

Goodwin M, Sanders C, Pretty I A . A study of the provision of hospital based dental general anaesthetic services for children in the northwest of England: part 1-a comparison of service delivery between six hospitals. BMC Oral Health 2015; 15.

Ashley P F, Williams C E C S, Moles D R, Parry J . Sedation versus general anaesthesia for provision of dental treatment to patients younger than 18 years. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 9: 10.1002/14651858.CD006334.pub4.

Shepherd A R, Hill F J . Orthodontic extractions: a comparative study of inhalation sedation and general anaesthesia. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 329–331.

Arch L M, G M. Humphris G M . Lee G T . Children choosing between general anaesthesia or inhalation sedation for dental extractions: the effect on dental anxiety. Int J Paediatr Dent 2001 11: 41–48.

Lyratzopoulos G, Blain K M . Inhalation sedation with nitrous oxide as an alternative to dental general anaesthesia for children. J Public Health Med 2003; 25: 303–312.

Ni Chaollai A ., Robertson S, Dyer T A, Balmer R C, Fayle S A . An evaluation of paediatric dental general anaesthesia in Yorkshire and the Humber. Br Dent J 2010; 209: E20.

Office for National Statistics. Population Estimates by Ethnic Group (experimental), Mid-2009. 2011. Available online at http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-50029 (accessed August 2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raja, A., Daly, A., Harper, R. et al. Characteristics of children undergoing dental extractions under general anaesthesia in Wolverhampton: 2007-2012. Br Dent J 220, 407–411 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.297

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.297

This article is cited by

-

Do paediatric patient-related factors affect the need for a dental general anaesthetic?

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

A rapid review of variation in the use of dental general anaesthetics in children

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Factors associated with use of general anaesthesia for dental procedures among British children

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

Comparing the profile of child patients attending dental general anaesthesia and conscious sedation services

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

Exploring the potential value of using data on dental extractions under general anaesthesia (DGA) to monitor the impact of dental decay in children

British Dental Journal (2017)