Key Points

-

Describes NICE guidance on antimicrobial prescribing.

-

Considers some of the implications of the guidance for commissioners and providers of NHS dental care services in England.

-

Highlights key recommendations for dental prescribers.

Abstract

Slowing the emergence of antimicrobial resistance is essential to ensuring antimicrobials remain an effective treatment for infections. Professor Dame Sally Davies, the UK Chief Medical Officer, has compared the threat posed by resistance to that from global terrorism. Antimicrobial use is a key driver of antimicrobial resistance, so reducing unnecessary prescriptions is a high priority. NICE has developed guidance aimed at optimising prescribing within publically-funded health and care services. With primary care dentists responsible for 5% of all NHS antibacterial prescriptions, the dental community has a role to play in guarding the effectiveness of antibacterial drugs. This article describes three recent NICE publications that have implications for dentists. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Systems and Processes (NG 15) is an overarching guideline for the NHS aimed at commissioners and providers of health and care services, together with more specific guidance for prescribers. Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis (CG64) was reissued in 2015 following a review of the latest evidence prompted by concerns that the incidence of infective endocarditis had increased since initial publication of CG64 in 2008. Changing risk-related behaviours of the public in relation to expectations for antimicrobial prescriptions is currently in production (PHG89) . This paper outlines the key recommendations from these NICE guidelines as they relate to the dental community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has risen alarmingly over the last 40 years and inappropriate use of antimicrobials is a key driver.1 The consequences of resistance include increased treatment failure for common conditions and fewer treatment options when antimicrobials are vital, such as during certain cancer treatments.2 All prescribers of antimicrobials have a role to play in guarding their use, so that they continue to be effective.

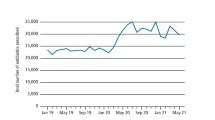

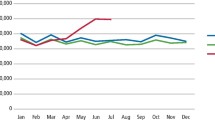

Across NHS England, primary care accounted for 82% and secondary care for 18% (11% hospital inpatients and 7% outpatients) of antibacterial prescriptions3 during 2014. NHS dentists prescribe more antibacterial drugs than any other medication.4 Some 3.7 million antibacterial prescriptions were dispensed by pharmacists in England4 for patients seen in dental practices, equating to 5% of all antibacterial prescriptions issued in the NHS in 2014.3 Dentists clearly have an important role to play in the stewardship of antimicrobials, but particularly of antibacterial agents.

In August and September 2015, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published three guidance documents (new guidance, draft guidance, and updated guidance) of which NHS dentists working in England need to be aware when prescribing antimicrobials:

-

Antimicrobial Stewardship: Systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use – NG15 (August 2015)5

-

Antimicrobial Stewardship: Changing risk-related behaviours in the general population – PHG 89 (draft for consultation September 2015)6

-

Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: Antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis for adults and children undergoing interventional procedures – addendum to CG64 (September 2015).7

Each of these documents has important recommendations for antimicrobials of relevance to prescribers, providers and commissioners of NHS dental services. The aim of this article is to outline some key aspects and new requirements.

Antimicrobial Stewardship (NG15)

Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) is an overarching term for systems and processes to optimise the use of antimicrobials and thereby improve patient outcomes and reduce AMR. While the General Dental Council (GDC) standards/guidance8 and Care Quality Commission (CQC) Fundamental Standards9 apply to all dentists practising in the UK, these new documents introduce more detailed requirements for those working with NHS patients in England. GDC, CQC and NG15 all specify that recognised guidelines should be followed when prescribing antimicrobials, but leave it up to the individual dentist to decide which guidance to choose. Evidence-based guidance on antibiotic prescribing for general dental practitioners has been published by the Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK) (FGDP).10 Guidance is also available in the British National Formulary (BNF)11 and there is a more user-friendly presentation of this information by the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP).12 FGDP, BNF and SDCEP guidance documents are all available online for free; links are included in the reference section to this paper.

The NG15 recommendations which relate to dental prescribers are set out in Figure 1. Because the recommendations have been written to be relevant across all primary and secondary care health and social care settings of the NHS, the terminology may at times appear unfamiliar. The onus is, therefore, on dentists to engage actively and consider how best to embed the concepts into routine practice. For example, when choosing an antibacterial, the risk of selecting for organisms causing health-care associated infections, such as Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), should be considered; if a dentist contemplates prescribing clindamycin its association with CDI13 is relevant and should be taken into account. Another of the NG15 recommendations states that an immediate prescription should not be given for self-limiting conditions; careful consideration is required, therefore, to decide whether prescribing aciclovir for an oral herpes simplex infection is appropriate.

Selected recommendations from NG15 relevant to dental prescribers5

In addition to recommendations for prescribers, NG15 also includes organisational-level recommendations for commissioners concerning the infrastructure to deliver and monitor AMS. Colleagues may also be interested in NICE's recommendations for the commissioners and providers of NHS services. Unlike the recommendations for prescribers, which are largely already addressed within existing requirements for dentists, the recommendations for commissioners and providers are not yet covered in all parts of the country in the dental context. Recommendations in this section include fostering of an open and transparent culture with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and encouraging senior health professionals to promote AMS within their teams, recognising the influence that senior prescribers can have on the prescribing practices of colleagues. Further recommendations for commissioners and providers from NG15 are set out in Figure 2 and a NICE Quality Standard is expected during 2016

Selected recommendations from NG15 relevant to commissioners and providers of NHS dental services5

Antimicrobial Stewardship – Changing Risk-Related Behaviour in the General Population – draft public health guideline (PHG89)

NICE is currently developing public health guidance which aims to help reduce AMR occurring and to stop it spreading by considering interventions to change people's behaviour. This includes making the general public aware of the importance of using antimicrobials correctly and the dangers associated with their overuse and misuse. Most of the draft guidance relates to local, national and international initiatives, such as the UK Antibiotic Guardian (www.antibioticguardian.com) initiative as part of European Antibiotic Awareness Day (18 November each year). Dentists are encouraged to play their role as health care professionals in championing this agenda and to make their pledge on the Antibiotic Guardian website. Options are available for members of the public, students and educators as well as healthcare professionals. Options for dentists to choose between are:

-

I will consider drainage for dental infections before issuing an antibiotic

-

I will discuss with patients the importance of antimicrobial resistance and encourage them to take the Antibiotic Guardian quiz and make a pledge to become an antibiotic guardian

-

When I see a patient with dental pain, I will discuss methods of controlling symptoms rather than prescribing antibiotics as a first course of action.

Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis (CG64)

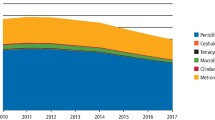

NICE has recently updated its guidance on antibiotic prophylaxis for infective endocarditis (CG64). Before it first published this guidance in 2008, NHS dentists in England prescribed some 130,000 prophylactic antimicrobial doses per year (or 10,900 per month7). Although this was a small proportion of the total number of antimicrobials prescribed by NHS dentists, this still represented a substantial selective pressure for development of AMR. After the introduction of CG64, prescribing of prophylactic antimicrobials for patients at risk of infective endocarditis fell dramatically.

In 2014, a study by Dayer et al.14 published in The Lancet investigating the impact of CG64, concluded that the incidence of infective endocarditis had increased significantly following the introduction of the NICE guideline. NICE initiated an immediate review of the latest evidence and the findings of its committee (which included topic experts in cardiology, dentistry and microbiology) were published in September 2015 as an updated guideline (only one section was updated and this was published as an addendum to the guideline).15 NICE identified a long-standing increase in the incidence of infective endocarditis across the world, not just in the UK. Independent expert statistical analysis of the Dayer paper undertaken as part of the evidence review by NICE found a high risk of bias; NICE concluded that there were many possible explanations for the increase in incidence and further research was needed. As a result, NICE guidance on antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis currently remains as per the 2008 guidance. An additional research recommendation was made: 'Does antibiotic prophylaxis in those at risk of developing infective endocarditis reduce the incidence of infective endocarditis when given before a defined interventional procedure?'7

The key part of CG64 (2008) for dentists remains the importance of:

-

Investigating and treating promptly any episodes of infection in people at risk of infective endocarditis

-

Giving clear and consistent advice to patients about prevention, including the importance of maintaining good ral health.

Summary

Antimicrobial resistance is a current and growing problem; dentists have an important role to play in reducing its development through improved antimicrobial stewardship. By optimising antimicrobial use, these guidelines aim to ensure the continued effectiveness of antimicrobial medication into the future without needing to treat patients with more broad spectrums and potentially toxic antimicrobials. For NHS prescribers in England, these guidelines are essential; for other prescribers, they provide a useful source of evidence-based guidance on antimicrobials.

References

NHS. Patient Safety Alert. Stage Two: Resources – Addressing antimicrobial resistance through implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship programme. Public Health England, 2015. Available online at https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/psa-amr-stewardship-prog.pdf (accessed January 2016).

Davies S. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2011: Volume Two. Department of Health, 2013. Avavilable online at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-volume-2 (accessed January 2016).

Public Health England. English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) 2010 to 2014: report 2015. Public Health England, 2015. Available online at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-surveillance-programme-antimicrobial-utilisation-and-resistance-espaur-report (accessed January 2016).

Prescribing and Medicines Team, Health and Social Care Information Centre. Prescribing by Dentists. HSCIC: England, 2014. Available online at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB17425/pres_dent_eng_2014_rep.pdf (accessed January 2016).

NICE. Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use NG15. NICE, 2015. Available online at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng15 (accessed January 2016).

NICE. Antimicrobial stewardship- changing risk-related behaviours in the general population. (In preparation) NICE, 2015. Information available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-phg89 (accessed January 2016).

NICE. Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures CG64. NICE, 2008. Available online at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg64 (accessed January 2016).

General Dental Council. Guidance on prescribing medicines. GDC, 2013. Available online at https://www.gdc-uk.org/Dentalprofessionals/Standards/Documents/Guidance%20Sheet%20Guidance%20on%20Prescribing%20Medicines%20September%202013%20v2.pdf (accessed January 2016).

CQC. How CQC regulates: primary care dental services. Care Quality Commision, 2015. Available online at http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20150611_dental_care_provider_handbook.pdf (accessed January 2016).

FGDP. Antimicrobial prescribing for general dental practitioners. updated 2014. Available online at http://www.fgdp.org.uk/OSI/open-standards-initiative.ashx (accessed January 2016).

NICE. British National Formulary. NICE, 2015. Available online at https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnf/current (accessed January 2016).

SDCEP. Drug prescribing for dentistry. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme, updated 2014. Available online at http://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/drug-prescribing/ (accessed January 2016).

Thornhill M H, Dayer M J, Prendergast B, Baddour L M, Jones S, Lockhart P B . Incidence and nature of adverse reactions to antibiotics used as endocarditis prophylaxis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 2382–2388.

Dayer M J, Jones S, Prendergast B, Baddour L M, Lockhart P B, Thornhill M H . Incidence of infective endocarditis in England, 2000–2013: a secular trend, interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet 2015; 385: 1219–1228.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Wendy Thompson is a general dental practitioner and is studying for a PhD (University of Leeds). During 2014/5, she was a member of the NICE AMS Guideline Development Group and is currently a member of the NICE Quality Standard Advisory Committee on AMS.

Dr Jonathan Sandoe is Associate Clinical Professor of Microbiology (University of Leeds) and Honourary Consultant Microbiologist at Leeds Teaching hospitals NHS Trust. In 2007/8 he was a member of the NICE CG64 Guideline Development Group and during 2015 was a member of the NICE Standing Committee A which reviewed CG64 on prophylaxis for patients at risk of infective endocarditis.

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, W., Sandoe, J. What does NICE have to say about antimicrobial prescribing to the dental community?. Br Dent J 220, 193–195 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.137

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.137