Key Points

-

Highlights that alcohol consumption is common and dentists have a role in the prevention of alcohol-related disease.

-

Indicates that screening can be a quick and simple method for identifying patients at risk.

-

Discusses how education and simple advice are forms of brief intervention.

Abstract

Alcohol is widely consumed by the majority of the UK population and alcohol-related harm is estimated to cost society £21 billion per year in healthcare, lost productivity costs, crime and antisocial behaviour. The dental setting offers an ideal opportunity to screen for harmful alcohol consumption; however, current emphasis is on the management of acute complications and risk associated in treating patients with excessive alcohol intake rather than screening and patient education. This article outlines ways in which dentists could improve their recognition of 'at risk' patients and then offer practical advice to help reduce the harmful effects of alcohol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alcohol is widely consumed by the majority of the UK population and has been identified as a causal factor in over 60 medical conditions including oropharyngeal cancers.1 In England, despite multiple health campaigns, mortality and morbidity caused by liver disease is rising, while decreasing in other European areas2 making alcohol a common preventable cause of premature death, along with smoking and hypertension.3 Alcohol-related harm is estimated to cost society £21 billion per year in healthcare, lost productivity costs, crime and antisocial behaviour.4 The dental setting offers an ideal opportunity to screen for harmful alcohol consumption; however, current emphasis is on the management of acute complications and risk associated in treating patients with excessive alcohol intake rather than screening and patient education. Both the British Dental Association5 and Department of Health6 have acknowledged that properly resourced and trained dentists could play a significant role in the detection and reduction of the harmful effects of alcohol in the general population.

The aim of this article is to outline ways in which dentists could improve their recognition of 'at risk' patients and then offer practical advice to help reduce the harmful effects of alcohol.

Recognising the 'at risk' patient

Almost one in four of adults in England drink alcohol at potentially harmful levels.7 Over the last decade it has been demonstrated that men and women aged over 45 are more likely to consume alcohol on five or more days per week compared with younger people who drink less frequently.8 However, harmful alcohol use, particularly dependence, most commonly begins in the early twenties.9,10

Definition

There is significant confusion in the definition of 'harmful alcohol use' with a multitude of terms being used to describe drinking habits. The term 'misuse' is applied to any level of risk, ranging from hazardous drinking to alcohol dependence. The WHO describes 'harmful' alcohol consumption as a pattern of psychoactive substance use that causes damage to health either physical or mental and commonly but not invariably, has adverse social consequences.11 'Hazardous use', in contrast, refers to patterns that are of public health significance despite the absence of any current disorder in the individual user. In a similar way, the Department of Health uses the terms 'increased risk' and 'higher risk' to describe drinking patterns. Alcohol 'dependence' is defined as a cluster of behaviours, cognitive and physiological phenomena that can develop after repeated substance use.12

Medical history and examination

Detecting the negative effects of excess alcohol consumption through the medical history and examination alone can be unreliable as not all patients who drink alcohol at harmful levels develop signs and symptoms and these often manifest gradually after many years of exposure.

The effects of chronic misuse are generally due to secondary end-organ damage to which a multitude of organs are susceptible (Table 1). The amount of alcohol needed to produce damage varies between individuals as a result of genetic, immunological and host factor differences. For example among heavy drinkers only 10% to 15% will develop liver cirrhosis.13,14 Other significant effects are subsequent to self-neglect and malnutrition as well as the development of alcohol dependence syndromes.

The liver is the organ most commonly affected by excess alcohol use, which can lead to a variety of symptoms. Patients may initially be asymptomatic, though persistent alcohol abuse can lead to the development of a fatty liver or advanced liver cirrhosis. Cirrhosis results in reduced liver function; including clotting factor synthesis, protein metabolism, glucose storage and hormone/drug inactivation, all of which may have implications for delivery of dental treatment.

There are a multitude of signs and symptoms that can be detected by careful examination of the clothed patient (Table 1). Dishevelled appearance, bruises from falls and injuries from fights should all ring alarm bells and although none of these are specific to alcohol misuse, they should warrant further enquiry. Patients dependent on alcohol can demonstrate neglect; reflected by poor oral hygiene, rampant caries and poor periodontal health during intra-oral examination. Folate and B-complex vitamin deficiencies associated with liver cirrhosis may be apparent, presenting with oral dysaethesia, glossitis and recurrent apthae. While extrinsic dental erosion may be evident in patients consuming acidic alcoholic beverages, intrinsic erosion may be a feature of alcohol-related gastrointestinal disease, frequent acid reflux or vomiting.

Because dental appointments are often of short duration and have a focus on oral health, the medical, social and psychological effects of alcohol can often go undetected. Targeted questioning about alcohol use is an efficient and sensitive way of assessing a patient's risk of harm that does not rely on the medical history and clinical examination.

Screening tools

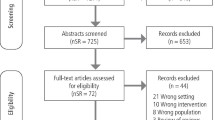

Several screening methods have been designed to help identify patients with alcohol-related disorders, some of which could be practically incorporated within the dental setting. The most commonly quoted CAGE questionnaire19 focuses on identifying alcohol abuse and dependence, whereas the more comprehensive Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (outlined in Table 2) makes an attempt to identify increased-risk drinking, both hazardous and harmful (Fig. 1). Shorter screening tools have been developed (for example, FAST, Paddington Alcohol Test and AUDIT-C) to suit settings where AUDIT is not always feasible such as emergency departments.

The three-question AUDIT-C screening tool, highlighted in red in Table 2, is a shortened version of AUDIT that remains sensitive to identifying patients at risk, and may be more acceptable in dental practice.

As with all screening tools, false positive and false negative results can arise from the screening process; for this reason the cut-off point at which a score is regarded as 'positive' varies among providers. Two studies found that scores of 4 or more for men and 3 or more for women using AUDIT-C were optimal for identifying hazardous drinking.20,21 Cut-off points as low as these will positively screen patients who are drinking on a regular basis (4 or more times per week), albeit within daily recommended limits, although this may be regarded as beneficial as patients often under-report their alcohol consumption. With regard to providing intervention, some providers will keep a cut-off score of ≥5 points to reduce the burden of false-positives.

It must be noted that screening tools are not diagnostic, but a positive total score should alert the dental practitioner, or healthcare professional, to offer appropriate intervention and/or refer the patient to their general medical practitioner or local alcohol service for further assessment.

Management

The dental team has been identified as a body that should be offering advice regarding alcohol consumption.5,6 The latest edition of Delivering better oral health (2014),22 an evidence-based toolkit published by Public Health England (PHE), includes a section on alcohol misuse and oral health, offering guidance to the dental team on improving the oral and general health of their patients with regards to alcohol consumption. Providing advice following screening of a patient can be challenging when not practiced on a regular basis, as delivery of information needs to be carefully structured and patient specific.

Introduction to Alcohol Brief Interventions

Alcohol Brief Intervention (ABI) is a low-cost and effective method to reduce drinking to lower risk levels.23,24,25 Most types of ABIs are based on the technique of 'motivational interviewing'.26 A review of 12 randomised controlled trials concluded that drinkers receiving a brief intervention were twice as likely to reduce their drinking over 6–12 months compared to those who received no intervention.20 This is highly effective when compared to smoking cessation advice, more commonly given by dentists, where evidence shows only 5% of people will act on the advice given to them, or 10% if nicotine therapy is offered.27

Studies have shown that patients expect dentists to ask them about alcohol and are in fact receptive to advice.15,16,17,18 However, despite the evidence supporting ABI, there has been little uptake of its use in the dental setting. Two studies of general dental practitioners (GDPs) in Scotland and the UK found that few GDPs are giving alcohol-related advice, yet there is scope and willingness to increase involvement.28,29 Lack of time, funding, training30 and low self-efficacy28 are significant barriers in the provision of this type of intervention in general dental practice. However, there is hope that the impending new dental contract (in England) would reduce some of these barriers with allocated sections/time addressing these components in the health assessment and review.

Assessing the need for intervention

An individual's risk for the harmful effects of alcohol consumption can be assessed via screening. Subsequent intervention should be appropriate and tailored to a patient's needs; this is applicable to both drinkers and non-drinkers. General guidelines by WHO and Public Health England in the Delivering better oral health toolkit describe interventions corresponding to AUDIT and AUDIT-C scores which can assist risk assessment of an individual patient (Table 3) but do not substitute for clinical judgement especially when higher scores are achieved or when using shorter screening tools. Studies carried out in veterans affairs hospitals in the United States have suggested that an AUDIT-C score of 6 or more is associated with gastrointestinal bleed (men under 50 years),32 8 or more is associated with the risk of fracture33 and 10 or more with increased mortality.34

Ultimately, the way in which patients respond to the advice given will be determined by their own attitude and readiness to change. As with other examples of health behaviour change, the 'stages of change' model35 can be applied.

Education

Alcohol education is useful for patients who are in the low-risk drinking category (for example, scores of 0-7 AUDIT or 0-4 AUDIT-C) and it can also be applied to those abstaining from alcohol. These patients may have partners or children drinking alcohol, hence education contributes to the general awareness of alcohol risks in the community. Alcohol education may serve as both a preventative measure and can act as a reminder for patients with past problems about the risks of return to hazardous drinking.31

Brief advice

This intervention is aimed at patients drinking hazardously (for example, scores of 8–15 AUDIT or 5+ AUDIT-C), but can benefit higher risk drinkers too. Of note, various bodies use the terms 'simple'29 and 'brief'22 interchangeably for this type of intervention; the term 'brief' advice will be used for the remainder of this article. NICE has acknowledged that the dental practice is an appropriate setting for this type of intervention.36 Although patients are willing to accept alcohol-related advice from their dentist, they may be surprised on the first occasion and dental practitioners need to be prepared for the different reactions encountered.

Following screening using AUDIT-C or AUDIT, the patient should be given feedback about their level of drinking. If scores are reflective of hazardous drinking or higher risks levels, patients should be encouraged to aim to reduce the risks associated with their level of drinking immediately. Establishing a goal is an important factor of brief advice. For some patients this may be reduction in alcohol intake, for others this could imply complete abstinence, for example, a pregnant woman. Patients should be provided with basic information about harmful effects of alcohol, including the physical, mental and social aspects. Units of standard drinks, daily and weekly limits should be explained. Visual aids and leaflets are useful for those who find it difficult to talk openly about their drinking and act as take home information, reinforcing the verbal consultation. This is particularly useful for patients in the pre-contemplation phase of the stages of change model, where they are not planning to change their behaviour in the near future, but may be unaware that their behaviour could be causing harm, or for patients in the contemplation phase, who are beginning to understand the problems associated with their behaviour and are debating whether to change. Encouragement is a key component to brief advice; patients should be welcomed to return for further advice should they need it and be informed of alternative places they can turn to for information and help. The key points to giving brief advice are outlined in Table 4.

Brief counselling

Scores as high as 16–19 using the AUDIT tool are often suggestive of harmful drinking or dependence and these patients are likely to be experiencing adverse physical, mental and social effects of alcohol consumption. For this reason, the WHO suggests a more thorough approach to intervention to include a combination of simple advice, brief counselling and continued monitoring of this patient group. Brief counselling comprises of either a short session of structured brief advice or a longer, more motivationally-based session.34 Although the goal of both simple advice and brief counselling are alike, the latter uses specific techniques to provide the patient with tools to change basic attitudes and therefore takes more time. With appropriate training, brief counselling can be carried out by non-alcohol specialists, including dentists.

Specialist referral

Patients suspected of alcohol dependence should be referred to a specialist for assessment and treatment. This typically applies to patients scoring 20 or over on the AUDIT questionnaire, however specialist treatment is not necessarily reserved for dependent patients; as those consuming alcohol at harmful levels may also necessitate this level of treatment, especially where there is associated psychiatric illness, a previous history of drug dependence, liver cirrhosis, or where counselling has failed. In these cases, patients should be encouraged to alert their general medical practitioner or other available alcohol service as soon as possible about their potential problem. Though not the primary treatment ABIs are not completely redundant in this group of patients as they can play a motivational role and help patients recognise they may need treatment. Guidance on useful websites, local community alcohol services and help groups should be made available to all patients should they seek further information or support. Caution must be taken when planning dental treatment in this group of patients; should liver cirrhosis be suspected, appropriate investigations should be undertaken or advice sought in order to manage these patients safely.

Conclusion

Alcohol consumption is considered socially acceptable in the UK, however its misuse is having an increasingly negative impact on the individual consumer and the wider society. Detection of alcohol misuse from medical history and examination alone can be difficult; screening tools that are appropriate for dental practice form a quick and effective method to aid in detecting higher risk drinking. ABIs are effective interventions that can be delivered in a dental setting, offering an ideal opportunity to reduce the alcohol-related harm in those who attend.

Stages of Change Model33

References

NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England in 2010. London: NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care, 2011. Online information available at www.ic.nhs.uk/pubs/sdd10fullreport (accessed 4 December 2014).

Davies S C . Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer, Volume one, 2011. On the State of the Public's Health. London: Department of Health, 2012.

Lim S S, Vos T, Flazman A D et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 2012; 380: 2224–2260.

House of Commons Health Committee. Government's alcohol strategy: Third report of session 2012–2013. London: House of Commons, 2012.

British Dental Association. The British Dental Association oral health inequalities policy. London: British Dental Association, 2009.

Department of Health. Modernising NHS dentistry – implementing the NHS plan. London: Department of Health, 2000.

National Centre for Social Research. Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: Results of a household survey. Leeds: NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care, 2009.

Office for National Statistics. General lifestyle survey 2011: An overview of 40 years of data. Office for National Statistics, 2013.

Grant B F, Stinson F S, Dawson D A et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61: 807–816.

Drummond D C, Oyefeso N, Phillips T et al. Alcohol needs assessment research project: The 2004 national alcohol needs assessment for England. London: Department of Health, 2005.

World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1993.

Mann R E, Smart R G, Govoni R . The epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res Health 2003; 27: 209–219.

Singal A K, Anand B S . Recent trends in the epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2013; 2: 53–56.

Miller P M, Ravenel M C, Shealy A E, Thomas S . Alcohol screening in dental patients: the prevalence of hazardous drinking and patients' attitudes about screening and advice. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137: 1692–1698.

Goodall C A, Crawford A, MacAskill S, Welbury R R . Assessment of hazardous drinking in general dental practice. J Dent Res 2006; 85: 1219.

Goodall C A, Welbury R R, Crawford A, MacAskill S . Do you take a drink? Asking patients about alcohol in general dental practice. Scottish Dentist 2007; March/April: 35–36.

Shepherd S, Young L, Bonetti D, Clarkson J, Ogden G . Alcohol advice in primary dental care. J Dent Res 2009; 87: Abs 0186.

Ewing J A ; Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 1984; 12: 1905–1907.

Bush K, Kivlahan D R, McDonell M B, Fihn S D, Bradley K A . The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDITC): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 1789–1795.

Bradley K A, Bush K R, Epler A J et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 821–829.

Public Health England. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 3rd ed. London: Public Health England, 2014.

Bien T, Miller W R, Tonigan J S . Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction 1993; 88: 315–336.

Kahan M, Wilson L, Becker L . Effectiveness of physician-based interventions with problem drinkers: A review. CMAJ 1995; 152: 851–859.

Wilk A, Jensen N, Havighurst T . Meta-analysis of randomized control trials addressing brief interventions in heavy alcohol drinkers. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12: 274–283.

Miller W R, Rollnick S . Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behaviour. New York: The Guilford Press, 2002.

Raistrick D, Heather N, Godfrey C . Review of the effectiveness of treatment for alcohol problems. London: National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse, 2006.

Shepherd S, Bonnetti D, Clarkson J E et al. Current practices and intention to provide alcohol-related health advice in primary dental care. Br Dent J 2011; 211: E14.

Dyer T A, Robinson P G . General health promotion in general dental practice – the involvement of the dental team. Part 2: a qualitative and quantitative investigation of the views of practice principals in South Yorkshire. Br Dent J 2006; 201: 45–51.

McAuley A, Goodall C A, Ogden G R, Shepherd S, Cruikshank K . Delivering alcohol screening and alcohol brief interventions within general dental practice: rationale and overview of the evidence. Br Dent J 2011; 210: E15.

Babor T F, Higgins-Biddle J C . Brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinking: a manual for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001.

Au D H, Kivlahan D R, Bryson C L, Blough D, Bradley K A . Alcohol Screening Scores and Risk of Hospitalizations for GI Conditions in Men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007; 31: 443–451.

Harris A H, Bryson C L, Sun H, Blough D, Bradley K A . Alcohol Screening Scores Predict Risk of Subsequent Fractures. Subst Use Misuse 2009; 44: 1055–1069.

Kinder L S, Bryson C L, Sun H, Williams E C, Bradley K A . Alcohol screening scores and all-cause mortality in male Veterans Affairs patients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009; 70: 253–260.

Prochaska J O, DiClemente C C . Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1983; 51: 390–395.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Public health guidance 24. Alcohol-use disorders: preventing the development of hazardous and harmful drinking. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, N., Goel, R., McGurk, M. et al. Brief advice on alcohol: as easy as A...B...I?. Br Dent J 218, 13–17 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.1138

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.1138