Key Points

-

Highlights that the global use of the International Classification of Disease could be a valuable tool to compare oral-health-related hospitalisations on an international scale.

-

Suggests that the NICE guidelines may have prevented the trends of hospitalisations for impacted teeth removal in England from skyrocketing as they have in Australia and France.

Abstract

Background The United Kingdom and its national healthcare system represent a unique comparison for many other developed countries (such as Australia and France), as the practice of prophylactic removal of third molars in the United Kingdom has been discouraged for nearly two decades, with clear guidelines issued by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2000 to limit third molar removal to only pathological situations. No such guidelines exist in Australia or France. The healthcare systems in England, France and Australia all use the International Classification of Disease (ICD) coding system for diagnostic categorising of all admissions to hospitals.

Aim This study rested upon the opportunity of a universal coding system and semi-open access data to complete the first comparative study on an international scale of hospitalisations for removal of impacted teeth (between 99/00 and 08/09).

Results Our international comparison revealed significant differences in rates of admission, with England having rates approximately five times less than France, and seven times less than Australia. Those results could be explained by the implementation of guidelines in the United Kingdom, and the absence of similar guidelines in France and Australia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately one fifth of humankind is affected by tooth impaction in some form,1 and in most cases it is caused by the upper and/or lower third molars.2,3

Surgical removal of impacted teeth in most developed countries is performed by a trained oral maxillofacial surgeon or oral surgeon (OMFS), and is commonly carried-out under general anaesthesia, in a hospital environment (generally involving one day's hospitalisation)4 with post-operative complications in up to 35% of the cases.5,6 Those complications can include sensory nerve damage (paraesthesia), alveolar osteitis (dry socket), infection, haemorrhage and pain. Rarer complications include severe trismus, oro-antral fistula, iatrogenic mandibular fracture and complications of general anaesthesia.

It has long been established that impacted teeth need to be removed when they show any sign of associated pathology and/or severe symptoms.7 However, in a considerable percentage of the extraction cases (from 18 to 60%),8,9,10,11 prophylactic extraction of pathology-free impacted teeth has been reported. The reasoning behind this controversial prophylactic procedure is the prevention of pathological changes, decrease in future surgical complications and improvement in post-orthodontic treatment retention (decrease of late incisor crowding). The justification for this prophylactic surgery is disputed and has been debated for many years. In a recent update, and after extensive review of the literature, the Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews8 concluded that there is not enough evidence supporting the removal of asymptomatic impacted third molars. Furthermore, the authors described watchful monitoring of these asymptomatic impacted teeth as a more prudent strategy.

The possibility of substantially decreasing the number of hospitalisations for impacted tooth extraction led to the introduction of the NICE Guidelines in 2000 in the UK.12 They were based mainly on the review of Song et al.13 and have been developed by a committee of 24 experts in health economics, epidemiology, public health and surgery. They recommended that the practice of extraction of pathology-free impacted third molars should be discontinued. Similar guidelines have also been established in 1999 by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).14 These unique guidelines have been followed by all dentists in the UK for the last 13 years.

This study analysed data from a ten-year period (1999-2009) by examining hospitalisations for impacted teeth removals, and to compare the healthcare systems of France and Australia with that of the United Kingdom. The hypothesis being that in the UK the rates of hospitalisation for impacted teeth are significantly less than that of the other jurisdictions.

Method

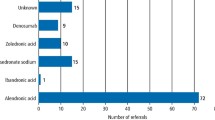

Hospitalisation data was collected for the three countries from open access sources for the United Kingdom and France. Data for Western Australia (one state of Australia) was obtained with ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee of The University of Western Australia, as the data was closed access. In all three jurisdictions data for all those patients with the principal diagnosis of 'K01: Embedded and Impacted teeth', as classified by the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10AM) system,15 was included in this study.

Western Australia

Data for analysis was obtained from the Western Australian Hospital Morbidity Data System (HMDS), for ten financial years, from 1999/2000 to 2008/2009, discharged from any private and public hospital in Western Australia. This state represents just over 10% of the total Australian population and covers nearly 50% of the geographic area of Australia. Population estimates for each year were derived from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

United Kingdom

Comparable freely available data for the decade was collected from the hospital episode statistics website (www.hesonline.nhs.uk)16 for the period from 1999-2000 to 2008-2009. All NHS trusts in England were included. The data also included private patients treated in NHS hospitals, patients resident outside of England but receiving care delivered by treatment centres (including those in the independent sector) funded by the NHS. No reliable data source was available for patients treated fully by the independent sector. As only 10% of population is covered by private insurance in the UK,17 their exclusion would not have had a significant effect on our comparative study. England's population estimates for each year were obtained from the Office for National Statistics, UK.

France

Comparable freely available data for the decade was collected from the hospital episode statistics website www.atih.sante.fr,18 derived from the National Information System on Hospitalisation (SNATIH) for the period from 1999 to 2008. All private and public hospitals in mainland France were included. French population estimates for each year were obtained from the French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE).

Recording periods

It is noted that there is a slight difference in recording periods as a financial year in the UK is from 1 April to 31 March, in France from 1 January to 31 December, while in Australia a financial year is from 1 July to 30 June; however it is not expected that this margin effect (over a decade of data) will have any effect on the data. If it does, the level of effect would be at best tiny, relative to the results of the study.

To establish a quantitative comparison between three differently sized populations, hospitalisation rates per 100,000 population/year were calculated (total population approximately 50 million), France (approximately 62 million) and Western Australia (approximately 2 million). These rates were not age standardised. All data was collated and analysed with Microsoft Excel (version 2003 Microsoft Corporation Redmont USA).

Results

Overall numbers

There were a total of 88,286 patients hospitalised in Western Australia for removal of impacted/embedded teeth during the ten-year period 1999-2000 to 2008-2009. The number of patients admitted to hospital for this condition per year increased by 81% over the study period (Fig. 1, Table 1), with an annual increase of between 1.2% and 23% per annum. In France, 1,834,613 patients were hospitalised for the same condition over the same period and the annual number increased by 36% over the decade. Most of the increase (32%) occurred between 1999 and 2005. In England 352,287 patients were hospitalised for impacted/embedded teeth. The number of patients admitted per year decreased by 20% over the study period. There was a sharp decrease of 61% between 1999/2000 and 2003/2004 followed by slow increase of 33% between 2003/2004 and 2008/2009 (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Rates of hospitalisation

A comparison of rates of hospital admissions for impacted teeth per 100,000 population in England, France and Western Australia is depicted in Figure 2. The rate changes over the period followed the same trends as the total number of admissions (Fig. 1). In 2004/2005 the rate for England was 61, France was 318 and Western Australia 455. This indicates that rates of admissions in Western Australia were significantly higher (740%) than England and (42%) higher than France. While on the other hand, in France the rates were significantly (520%) higher than England. Toward the end of the study period (2008/2009), this difference remains substantial with Western Australian rates 690% higher than England and 60% higher than France. Similarly, rates in France were 430% higher than England.

Discussion

Removal of impacted teeth under general anaesthesia offers the possibility of extracting multiple teeth at one admission, less discomfort to the patient, and thus the intention of providing a more cost-effective and efficient service, and also allows more visibility to the oral surgeon.

Hospital admission rate recording for this purpose also offers the opportunity to closely monitor the trends of this practice over time, in a given healthcare system and on a large scale. This is particularly important when considering that a considerable percentage of the overall impacted teeth removals are performed as an in-office procedure,4 which is very difficult to monitor in a statistically reliable way. The healthcare systems in the UK, France and Australia all use the International Code of Diagnostics (ICD) coding system for diagnostic categorising of all admissions to hospitals. As the same coding system is used for hospitalisations for removal of impacted/embedded teeth in those three countries, it was possible to draw the first comparative study on an international scale regarding hospitalisations for removal of impacted teeth (mainly third molars).2,3

Our international comparison revealed significant differences in rates of admission for impacted teeth, which could be explained by the implementation of NICE guidelines in the United Kingdom and the absence of similar guidelines in France and Australia. As these countries are very comparable in terms of most factors affecting third molar pathology and the way dental services are delivered, other contributing factors such as insurance policies, cost of treatment and the number of oral maxillofacial surgeons and stomatologists – in the case of France – could not alone explain such substantial differences. Furthermore, those contributing factors could be closely related, as in the case of insurance policies and cost, to the presence/absence of the guidelines.

Interestingly, despite the fact that the vast majority of the research done on the role of third molars on anterior crowding revealed no significant effect,19,20,21,22 many OMF surgeons and orthodontists still believe that the erupting third molars are capable of pushing the anterior teeth forward, causing anterior crowding.23 As removal of third molars has been performed in order to prevent abnormal orthodontic conditions,24,25,26 it is likely that this purpose would be responsible for a considerable percentage of the cases in France and Australia.

Western Australia is the largest state of Australia with a population of around 2 million, which is a reasonably representative sample of the Australian healthcare system. We have previously27,28,29 examined the practice of hospitalisation for removal of impacted teeth in Western Australia and shown the high related expenditure and the significance of associated factors such as indigenous status, age, gender and private hospital access along with insurance status. This study has clearly shown that the rates of hospitalisations for impacted teeth removal in Western Australia are substantially higher than the rates in UK and higher (but to a lesser extent) than the rates in France. These findings should be of interest to both healthcare authorities, and insurance companies, as it does present a significant economic impact, and also the possibility of some unnecessary hospitalisations, thereby further burdening the health system.

The impact of guidelines on the practice of third molar extraction in the UK has been reviewed by Renton et al.30 and by McArdle and Renton.31 Between 1988 and 1994 the number of episodes in the UK was on the rise and increased by one-third.11 An overall decrease of numbers of third-molar-related hospital admissions was observed since the RCS guidelines were introduced in 1997, with a late slow increase since 2005, which has been attributed to rebound effect mostly caused by dental caries at an older age.30,31 Those findings were found to be consistent with our analysis of the trends in England between 1999 and 2008.

The first reports on the third molar removal controversy in UK were published by Brickely and Shepherd and others,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 between 1993 and 1996. Their work, as well as the extensive media coverage on this issue in the UK30 has led to the development of RCS39 guidelines in 1997 followed by SIGN14 guidelines in 1999.

The first review of Song et al.40 (1997) and the subsequent commentary by Shepard41 (1998), together with the final report of Song et al.13 (2000) have been the basis upon which the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued their guidelines regarding third molar management in 2000.12 They recommended that the practice of extraction of pathology-free impacted third molars should be discontinued and to limit this practice to patients with evidence of pathology. However, they only recommended a standard routine programme of dental care for pathology-free impacted third molars. This was recently criticised by Mansoor et al.,41 citing the need for periodical panoramic radiography examination of impacted teeth, even in the absence of symptoms and signs. Furthermore, in view of their reported increase of caries to adjacent teeth, a more focused surveillance of mandibular third molars has been suggested by Renton et al.30 Those recommendations are consistent with the strategy of watchful monitoring of pathology-free impacted teeth, prescribed by the Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews.8

Conclusion

The key finding from the present study was that there appears to be very significant differences in the rates of hospitalisation for impacted teeth across the world and raises the potential that the presence of good-quality clinical guidelines for dental procedures, especially those requiring access to high cost health system facilities and treatment, has the potential long-term opportunity to more efficiently, and cost effectively manage care and target it to those most in need.

References

Andreason J O . Textbook and atlas of tooth impactions: diagnosis, treatment, prevention. pp 222–223. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1997.

Chu F C, Li T K, Lui V K, Newsome P R, Chow R L, Cheung L K . Prevalence of impacted teeth and associated pathologies – a radiographic study of the Hong Kong Chinese population. Hong Kong Med J 2003; 9: 158–163.

Brakus I, Filipovic Z, Boric R, Siber S, Svegar D, Kuna T . Analysis of impacted and retained teeth operated at the department of Oral Surgery, School of Dental Medicine, Zagreb. Coll Antropol 2010; 34: 229–233.

Worrall S F, Riden K, Haskell R, Corrigan A M . UK National third molar project: the initial report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 36: 14–18.

Mercier P, Precious D . Risks and benefits of removal of impacted third molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992; 21: 17–27.

Chipasco M, Crescentini M, Romanoni G . Germectomy or delayed removal of mandibular impacted third molars: the relationship between age and incidence of complications. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995; 53: 418–422.

NIH. Consensus development conference for removal of third molars. J Oral Surg 1980; 38: 235–236.

Mettes T D, Ghaeminia H, Nienhuijs M E, Perry J, van der Sanden W J, Plasschaert A . Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 6: CD003879.

Dunne C M, Goodall C A, Leitch J A, Russel D I . Removal of third molars in Scottish oral and maxillofacial units: a review of practice in 1995 and 2002. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006; 44: 313–316.

Lopes V, Munmenya R, Feinmann C, Harris M . Third molar surgery: an audit of the indications for surgery, post-operative complaints and patient satisfaction. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995; 33: 33–35.

Liedholm R, Knutsson K, Lysell L, Rohlin M . Mandibular third molars: oral surgeons assessment of the indications for removal. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999; 37: 440–443.

NICE. Guidance on removal of wisdom teeth. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2000.

Song F, O'Meara S, Wilson P, Golder S, Kleijnen J . The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of prophylactic removal of wisdom teeth. Health Technol Assess 2000; 4: 1–55.

SIGN. Management of unerupted and impacted third molar teeth. Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1999.

National Centre for Classification of Health. The International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision. Australian Modification (ICD10 AM). Vol. 1–5. Lidcombe, Australia, 2000.

Health & Social Care Information Centre. Hospital Episode Statistics. Online information available at www.hesonline.nhs.uk (accessed January 2014).

Office of Health Economics. OHE guide to UK Health and Health Care Statistics. p 69. London: Office of Health Economics UK, 2011.

Agence technique de l'Information sur l'hospitalisation (ATIH). Online information available at: www.atih.sante.fr (accessed January 2014).

Bishara S E, Andreasen G . Third molars: a review. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1983; 83: 131–137.

Ades A A, Joondeph D R, Little R M, Chapko M K . A long-term study of the relationship of third molars to the changes in the mandibular dental arch. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1990; 97: 323–335.

Harradine N W T, Pearson M H, Toth B . The effect of extractionof third molars on late lower incisor crowding: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Orthod 1998; 25: 117–122.

Karasawa L H, Rossi A C, Groppo F C, Prado F B, Caria P H . Cross-sectional study of correlation between mandibular incisor crowding and third molars in young Brazilians. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2013; 18: e505–509.

Lindauer S J, Laskin D M, Tüfekçi E, Taylor R S, Cushing B J, Best A M . Orthodontists' and surgeons' opinions on the role of third molars as a cause of dental crowding. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 132: 43–48.

Lindqvist B, Thilander B . Extraction of third molars in cases of anticipated crowding in the lower jaw. Am J Orthod 1982; 81: 130–139.

Niedzielska I . Third molar influence on dental arch crowding. Eur J Orthod 2005; 27: 518–523.

Godfrey K . Prophylactic removal of asymptomatic third molars: a review. Aust Dent J 1999; 44: 233–237.

George R P, Kruger E, Tennant M . Hospitalisation for the surgical removal of impacted teeth: Has Australia followed international trends? Australas Med J 2011; 4: 425–430.

George R P, Kruger E, Tennant M . The geographic and socioeconomic distribution of in-hospital treatment of impacted teeth in Western Australia: a 6-year retrospective analysis. Oral Health Prev Dent 2011; 9: 131–136.

George R, Tennant M, Kruger E . Hospitalisations for removal of impacted teeth in Australia: a national geographic modeling approach. Rural Remote Health 2012; 12: 2240.

Renton T, Al-Haboubi M, Pau A, Shepherd J, Gallagher J E . What has been the United Kingdom's experience with retention of third molars? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 70(Suppl 1): S48–57.

McArdle L W, Renton T . The effects of NICE guidelines on the management of third molar teeth. Br Dent J 2012; 213: E8.

Brickley M, Shepherd J, Mancini G . Comparison of clinical treatment decisions with United States National Institutes of Health consensus indications for lower 3rd molar removal. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 102–105.

Shepherd J P, Brickley M . Surgical removal of 3rd molars. BMJ 1994; 309: 620.

Brickley M, Kay E, Shepherd J P, Armstrong R A . Decision analysis for lower third molar surgery. Med Decis Making 1995; 15: 143.

The British Society for Dental Research (A Division of the IADR) 43rd Annual Meeting April 10-13, 1995 University of Manchester England. J Dent Res 1995; 74: 814–900. Abstract: Cowpe J G, Armstrong R A, Evans D J et al. Patient perceptions regarding the costs and benefits of lower 3rd molar removal: 876.

British Society for Dental Research The British Division of the IADR 44th Annual Meeting April 1-4, 1996 Bristol, England. J Dent Res 1996; 75: 1122–1202. Abstract: Armstrong R A, Brickley M R, Shepherd J P. The use of multiattribute utilities to refine third molar treatment policy: 1195.

British Society for Dental Research The British Division of the IADR 44th Annual Meeting April 1-4, 1996 Bristol, England. J Dent Res 1996; 75: 1122–1202. Abstract: Brickley M R, Shepherd J P. Performance of a computer simulation of lower third molar eruption: 1164.

Brickley M R, Tanner M, Evans D J, Edwards M J, Armstrong R A, Shepherd J P . Prevalence of third molars in dental practice attenders aged over 35 years. Community Dent Health 1996; 13: 223–227.

Royal College of Surgeons of England Faculty of Dental Surgery. The Management of Patients with Third Molar Teeth: Report of a Working Party Convened by the Faculty of Dental Surgery. London: Royal College of Surgeons of England Faculty of Dental Surgery, 1997.

Song F, Landes D P, Glenny A M, Sheldon T A . Prophylactic removal of impacted third molars: an assessment of published reviews. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 339–346.

Shepherd J P . Little justification for the removal of pathology-free third molars. Evid Based Dent 1998; 1: 11.

Mansoor J, Jowett A, Coulthard P . NICE or not so NICE? Br Dent J 2013; 215: 209–212.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anjrini, A., Kruger, E. & Tennant, M. International benchmarking of hospitalisations for impacted teeth: a 10-year retrospective study from the United Kingdom, France and Australia. Br Dent J 216, E16 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.251

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.251

This article is cited by

-

Socioeconomic disadvantage and oral-health-related hospital admissions: a 10-year analysis

BDJ Open (2016)

-

Cost effectiveness modelling of a 'watchful monitoring strategy' for impacted third molars vs prophylactic removal under GA: an Australian perspective

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Summary of: International benchmarking of hospitalisations for impacted teeth: a 10-year retrospective study from the United Kingdom, France and Australia

British Dental Journal (2014)