Key Points

-

Identifies an oral health need in a previously unstudied population.

-

Provides a methodology for data collection in a potentially difficult-to-access population.

-

Shows the impact of oral health on mental health status.

-

Provides potential areas to focus oral health promotion in people with severe mental illness.

Abstract

Objectives To describe the prevalence of oral diseases and their impact on oral-health-related quality of life in people with severe mental illness undertaking community-based psychiatric care.

Methods A survey was conducted at eight outpatient psychiatric care clinics in Tower Hamlets, London, UK. One hundred and twelve consecutive patients with mental illness were invited to participate in this study. They were clinically examined and asked to complete the oral health impact profile (OHIP) questionnaire.

Results The response rate was 79% (n = 89); 57 (64%) males and 58 persons over 45 years of age (65%) participated in this survey. Overall OHIP score was 25.4 (95% CI 23.3, 27.4), 70 (78%) were smokers and 45 (51%) had been to the dentist in the last two years. Forty-seven (53%) respondents had caries in at least one tooth, 60 (67%) had 21 teeth and more, and 14 (16%) used dentures. Advanced periodontal treatment was indicated in 42 (55%) of patients and 52.8% (n = 47) patients reported current pain.

Conclusion Overall, this survey found that oral health has a great impact on patients with severe mental illness being treated in the community setting and their oral health is poorer than the national adult general population. Future research should consider the causes that relate to the poorer oral health in this population and potential health promotion mechanisms in this population to encourage an upstream approach to health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

National surveys to measure the prevalence of oral diseases and their impact on oral-health-related quality of life are key to many public health systems. They aid policy makers to make decisions on priority areas and allocation of resources to address those priorities. However, it is well established that certain groups of the community suffer a higher burden of disease. These groups are usually under-represented in national surveys and a closer look is necessary in order to facilitate the work of policy makers and service planners in targeted approaches. One group of the community that is growing in number and that have hardly been surveyed are adults with severe mental illness who are in outpatient, community-based psychiatric care.

Mental illness is described as 'a clinically recognisable pattern of psychological symptoms or behaviour causing acute or chronic ill-health, personal distress or distress to others'.1 It affects many aspects of the individual's life, including educational performance, employment, personal relationships, income, social participation and consequent patterns of behaviour.2 Social exclusion and lifestyle habits such as reduced physical inactivity, smoking and poor nutrition, as well as adverse effects to related medication, result in this group having poorer general health than the rest of the population.3 Evidence suggests that individuals with mental illness die an average 10-15 years earlier than the general population and are at a much greater risk of acquiring secondary medical conditions.4

Despite adversities, many individuals with mental illness are able to interact with other members of the society in a normal way. The old view that these individuals should be placed in specialised care units is long gone and there are growing numbers of individuals who are treated in outpatient care units. More than ever, their self-perception of health and the impact their health has in day-by-day activities are important for their participation in community life, avoidance of social exclusion and their overall quality of life.5

There are reasons for us to believe that individuals with severe mental illness will suffer a greater impact on their oral-health-related quality of life. In the dental context, quality of life considers an individual's level of pain, ability to function dentally and the psychological impact of their dental state. As many dental diseases such as periodontal disease, caries, and tooth wear have causative factors related to lifestyle factors such as diet, nutrition and tobacco use, it may be that this leads to higher prevalence of dental diseases in this population.2 Additionally, mental illness, especially with increased severity, leads to deterioration in self-care, with oral health having a low priority.5 Evidence shows that there is a complex relationship between an individual's mental illness, socio-economic status and the nature of dental treatment that influences oral health, with low levels of perceived need, lack of awareness of dental services, anxiety and negative dental staff attitudes acting as barriers to dental care.6

To date, oral health studies involving patients with mental illness have been mostly undertaken in inpatient settings and have focused purely on traditional normative measures of oral health, such as number of decayed, missing and restored teeth.7 Little work has been done with people accessing community mental health support. Community mental health teams (CMHT) aim to help people with a mental health illness live in the community and provide support on health and social care with the aim of integrating the individual to the society by providing support in a range of life factors. The CMHT have a multidisciplinary team of mental health professionals to support people with mental health issues, however, compliance of medication and attendance to sessions is user dependent and there is a risk that patients will not access the services available. It is therefore important to consider the oral health care needs of people in community-based psychiatric care independently. Whereas institutionalised patients will have access to healthcare workers continually within the institution, people in community mental health care may not and are at risk of being under served. In addition to this, little insight has been given to the expressed need and impact that oral health has on an individual with mental health issues' daily life, despite the fact that oral health may impact a person functionally, psychologically and socially, as well as causing pain or discomfort.8

Oral health is an important aspect of quality of life, which affects comfort, appearance and social acceptance9 and as many mental illnesses are related to self-esteem and confidence issues, oral-health-related quality of life is a particularly important factor in patients with mental illness.10

It is therefore the aim of this study to describe the prevalence of oral diseases and the oral-health-related quality of life in people with severe mental illness undertaking community-based psychiatric care.

Materials and methods

Sample

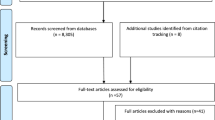

From the community mental health trust register in Tower Hamlets, it is estimated that there are 1,185 adults living with severe mental illness being treated in community care in January 2010. Therefore, a sample size of 89 participants was calculated.

Access to the severe mental illness register was not possible (with respect to patient confidentiality), thus sample selection was purposive and was undertaken at 8 of the 12 community mental health trust sites that patients would attend for appointments. The other four sites were medical practice based and did not agree to participate in this study due to potential disruption to the running of daily practice.

Dates that the researcher was attending were advertised at the sites before and on the day of data collection to maximise participation and provide all clients a fair chance of participating in the research. All patients attending the mental health sites were included in the research and the first 89 participants were sampled. Patients were excluded if they could not give full and valid consent, if they were unable to complete the questionnaire due to their level of English or if they had been sampled at an alternate site. Community mental health sites were chosen as the sampling site as this would enable a broad sample irrespective of dental history or potential anxiety.

Data collection

Participants were asked to fill a self-complete questionnaire and to have their mouths clinically examined.

The questionnaire included questions on demographic characteristics, self-reported health behaviours such as smoking, alcohol, oral-health-related behaviours and the OHIP-14 scale.

Oral-health-related quality of life is a measure based on how the individual evaluates the impact of the factors relating to their oral health and is most commonly used in its 14-question form (OHIP-14), which is a modification of the original 49-item scale.10 The OHIP-14 explores seven domains; functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability and handicap; each of which is assessed by corresponding questions. Participants are required to respond with one of five possible answers: never, sometimes, occasionally, often and very often. Studies show that the OHIP-14 has good validity, stability and consistency and is used in the UK national oral health survey.11 Although intended to be self administered, in this study it was completed at the interview to minimise non-completion and overcome issues of non-literacy.

Clinical examination for oral heath status followed the examination and diagnostic criteria of the Adult Dental Health Survey (ADHS) 2009,12 and was undertaken by a trained and calibrated examiner (RP). Data on tooth loss, natural tooth condition, restorative status and the condition of supporting tissues was collected. Due to anxiety, participant cooperation and unclear medical histories, the periodontal probing followed the shorter community periodontal probing index (CPI) assessment, rather than the national collection method.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was sought at local and national level. Locally by the East London Ethics Committee and nationally by the National Research and Ethics Committee (application reference 137). The application was reviewed by the South West 4 Research and Ethics Committee (application reference 10/H0102/42). Further to the NRES approval, research and development approval at Barts and the London NHS Trust was confirmed (application reference 007,228).

All participants gave informed written consent for the interview and clinical examination independently. As a result of the clinical examination, all participants and carers were informed of their dental status, and with their approval a referral to the appropriate dental treatment service, be it general, hospital or community dental services was completed.

Data analysis

Data from the questionnaire and clinical examination was coded and entered into SPSS Version 17 for analysis, and data entry errors were checked by reassessing ten entries for accuracy. Descriptive statistical analysis was undertaken

Composite measures of oral health as in the Adult Dental Health Survey (2009)12 were calculated. These included functional dentition according to the shortened dental arch theory, categorisation of tooth wear, periodontal treatment need and excellent oral health.

Results

Of the 112 participants invited, 89 accepted the invitation and participated in the research, which gave a resultant response rate of 79%. Reasons for those that did not want to participate included not having time, non-English speaking and not wanting to see a dentist; while others gave no reason.

The demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Thirty-one percent of the participants were between 45 to 54 years of age with more males (64%; n = 57) than females making up the sample.

The majority of respondents had experience of smoking tobacco, with 78.1% (n = 70) being current smokers and 2.2% (n = 2) previous smokers. Those that were current smokers also had a high rate of smoking, with the average smoker having 16 cigarettes/roll-ups per day (95% CI 13.2, 18.8). The range of number smoked was from 5 to 60, with most respondents smoking 15 a day. Four (4.5%) of the respondents chewed oral tobacco, which ranged from once to six times a day.

Alcohol consumption on the whole was low in this population group, with 69.7% (n = 62) not consuming alcohol. Of those that responded positively to consuming alcohol, most (28.1%, n = 25) reported consuming one to ten units per week, with 2.2% (n = 2) of respondents consuming 21 or more units per week.

Access to dental care was poor in this population group, with less than half (41.6%, n = 37) currently having a dental practice that they regularly and repeatedly attended. Forty-five (50.6%) of the respondents had visited the dentist within the last two years, although only 28 (31.4%) had done so in the last six months. Of those that had attended longer than two years ago, 15 (16.9%) had done so in the last five years. A high proportion (32.6%, n = 29) of respondents had not visited the dentist in longer than five years.

Oral-health-related quality of life

The mean OHIP score for the sample was 25.4 (95% CI 23.3, 27.4) with the minimum score of 0 and a maximum of 32 and a median of 23. The potential maximum score, if all questions were answered as 'very often' would have been 56. No respondents were affected by all 14 impacts, whereas 20.2% (n = 18) reported no impacts at all. The highest number of items reported were five and six, which were both reported by 10.1% (n = 9) of the respondents. The mean number of impacts was 4.73 (95% CI 3.96, 5.49), with 47.2% (n = 42) reporting less than the mean number of impacts and 52.8% (n = 47) of respondents reporting five or more impacts. Table 2 displays the distribution of responses to the statement scale based on the seven domains of the OHIP-14.

The physical pain domain reported the most impact, with 79.8% (n = 71) reporting painful aching or discomfort upon eating in the past year. However, in only 61.8% (n = 55) of cases did this translate into physical disability relating to an unsatisfactory diet or meal interruptions. The two items indicating social disability were reported as having the lowest impact, with only 9% (n = 8) of respondents having issues doing their usual jobs, or becoming irritable with other people as a result of their oral condition. Further to this, only 17.3% (n = 16) had reported limitations in function, be it speech or taste. In terms of psychological impacts, 64% (n = 57) reported psychological discomfort, with 56.1% (n = 50) reporting a psychological disability.

When considering the items individually, discomfort upon eating was the most frequently reported impact (64.0% n = 57), followed by an unsatisfactory diet and pain (59.6% n = 53 each). The most unreported impact was not being able to function, which was considered in only one case (1.1%) Importantly, over half of the respondents (53.9% n = 48) considered that their quality of life was affected by their oral health.

Clinical oral health status and care needs

Of the 89 participants, 7 (7.9%) were edentulous, whereas 92.4% (n = 82) had at least one or more natural teeth remaining. Of the 82 dentate participants the mean number of natural teeth present was 23.3 (95% CI 21.6, 24.6) with a median of 25.5 and a range from 4 teeth to a full dentition of 32 teeth. Of the dentate patients 26.8% (n = 22) possessed fewer than 21 natural teeth and so had a non-functional dentition. Nationally 6% of adults were edentulous with the mean number of teeth present in dentate adults of 25.7 and 14% possessing fewer than 21 teeth (ADHS, 2009).12

In the sample of dentate respondents 79.3% (n = 65) had some visible debris, with a mean of 14.4 (95% CI 12.0, 14.4) debris teeth. 86.6% (n = 71) of respondents had calculus on at least one tooth with a mean 12.9 (95%CI 10.7, 15.1) teeth with calculus present.

Table 3 presents the proportion of people requiring clinical treatment for dental conditions. Treatment needs were high, as reflected in the high mean for decayed teeth. The sample had a mean number of decayed teeth of 1.88 (95% CI 1.0, 2.7), with a range of 0 to 24 and median of 1.47. Two percent (n = 42) had no evidence of decay, with 3.3% (n = 3) having widespread decay with 17 or more teeth. Over half the respondents had decay in at least one tooth (52.8%, n = 47) with 20.3% (n = 8) having more carious teeth than the mean. The sample had a mean on 3.5 filled teeth (CI 2.8-4.1) with a range of 0-14 and median of 3.

The periodontal results show that 93.9% (n = 77) of dentate respondents required periodontal treatment. Of these respondents, 54.5% (n = 42) required more advanced periodontal treatment (CPI score 3 or 4), with the remaining 45.4% (n = 35) requiring simple periodontal treatment and/or oral hygiene instruction (CPI 1 or 2). Only 6.1% (n = 5) of respondents required no periodontal treatment.

Pain was the most reported concern in this sample, with 52.8% (n = 47) reporting current pain and 3.4% (n = 3) presenting with a periodontal or dental abscess. No participants had any tissue ulceration or fistulas.

The 2009 ADHS12 introduced 'excellent oral health' as a composite measure of oral health, which combines several clinical measures to identify adults with best current health. In this sample of 89 participants, none met the requirements to be deemed as having excellent oral health.

Discussion

The results of this survey show that oral health has a great impact on patients with severe mental illness being treated in the community setting, and based on the data from the clinical variables tested, oral health in this population is poorer than the general population.

Health behaviours

Results from this study relating to health behaviours were in keeping with previous findings. Hughes and Frances13 reported increased rates of smoking in this population. In this study, it was found that a high number of participants (78.1%) (n = 70), smoked cigarettes and a further 4.5% (n = 4) also chewed oral tobacco. Contrary to current literature,14 this study found alcohol consumption on the whole to be low, with 69.7% (n = 62) of participants not consuming alcohol at all. It must be noted, however, that a large proportion of residents in Tower Hamlets would not consume alcohol due to religious beliefs, and that previous studies were not undertaken on a comparable ethnic population. Research by Ponizovsky et al.,15 Dickerson et al.16 and Farnam et al.17 supports the findings of this study in that patients with severe mental illness have reduced dental attendance. The results of this study found that less than half (41.6% n = 37) of respondents currently had a dental practitioner, and that approximately half (50.6%, n = 45) had visited a dental practitioner in the last two years. This should be compared to the national data whereby 58% of adults surveyed had tried to make an NHS dental appointment in the last three years and 92% were successful in attaining an NHS appoint for urgent or routine care.

Quality of life

This study is the first in this population group, and is directly comparable with data from the oral health needs assessment of the general adult population. Data collection was undertaken by an examiner who was trained and calibrated to undertake the national survey and the methodology utilised in this study matched the national data collection method to support the reliability of the examinations and provide the opportunity to directly compare the oral health needs of patients with severe mental illness and how this may differ from the general population.

Reported oral-health-related quality of life is worse in the population suffering from severe mental illness in this study, than nationally. In this survey, 79.8% (n = 71) of respondents reported having one of more oral health impacts on their quality of life, compared to 39% from the national survey. In both surveys, the most frequently reported impact was physical pain with the highest proportions of respondents reporting painful aching in the mouth and finding it uncomfortable to eat any foods, although this was reported more frequently in this survey (79.8%, n = 71) than nationally (30%). In this survey, OHIP related to pain in the last year. If we relate this to the clinical measure of current pain, 53.8% (n = 47) reported positively. Thus, many respondents have been in continuing pain over the last year and currently still are.

Clinical data

When compared to national data, the results of this study show that patients with severe mental illness in community-based psychiatric care have worse oral health that the national adult population.

There were more edentulous persons than nationally, with more missing teeth and lack of functional dentitions than national values. In the national adult dental health survey (2009) survey 94% of adults were dentate, with a mean of 25.7, compared to patients with severe mental illness in which 92.4% were dentate, with a mean of 21.5 teeth. The number of dentate adults nationally (94%) was similar to this sample group (92.4%), however, patient with severe mental illness that were dentate had on average 4.2 less teeth than nationally. Thus the study had more missing teeth on average (10.5) than the national figure (7.2) for missing teeth, and consequently the proportions of all subjects with a functional dentition were higher nationally (72%) than in the study population (67.4%, n = 6). Additionally, whereas 95% of subjects nationally had natural teeth in both arches, this fell in the population with severe mental illness to 89.9% (n = 81). Kumar et al.18 postulated that the higher level of tooth loss in this patient group was related to reduced dental attendance, whereby people with severe mental illness did not access care as frequently and therefore had more aggressive treatments undertaken such as extractions, as they presented with more advanced dental disease states.

In relation to natural teeth present and their status, the mean number of sound teeth in this sample was 16, with a mean of 1.88 carious teeth. The national adult population had more sound teeth present (17.9) with a mean of 0.8 carious teeth. This is not an appropriate measure of disease, as a high proportion in the group had no dental decay. In the general adult population 31% had a sound dentition; this was the case in only 7.9% of patients with severe mental illness. On average, patients with severe mental illness had less filled teeth (3.5) than than the national average (7.9). An increased level of decay and reduced number of filled teeth supports findings from previous studies, in the reduced access to dental care in this sample group.

With regards to oral hygiene and periodontal health, debris scores were better than the general population in the area, although worse than the national average. In this sample 79.3% (n = 65) of participants had visible debris, compared to 66% nationally. The mean number of teeth with debris in the sample with severe mental illness was 14.4, compared to 6.0 nationally. The number of respondents with calculus in this sample (86.6% n = 71) was higher that the national population (68%).

When considering composite measures of oral health, no patients with severe mental illness had excellent oral health as defined by the 2009 ADHS,12 whereas one in ten adults matched the criteria nationally.

Previous studies show that there is a complex relationship between an individual's mental illness, socio-economic status and the nature of dental treatment that influences oral health.

Limitations to this study are predominantly around the sampling method. Limited access to the severe mental illness register and uneven agreement from clinics to participate will have resulted in sampling bias, as not all patients will have had the opportunity to participate in the research. In addition to this, there may have been a selection bias as the interview/oral examination situation might result in greater participation by a healthier group, as it appeals to participants who already enjoyed good oral health and who found staying healthy an important issue in their lives. Patients disinterested in their oral health or those with dental anxiety might therefore have avoided participation in the project. Exclusion of non-English speaking participants may additionally have meant that some of the population who would have participated may not have been sampled.

Due to potential confounding factors that apply to this population, this data is not inferable to the whole population with severe mental illness. However, as discussed at length in the literature review, there is very little research undertaken on the oral health of outpatients with severe mental illness due to the difficulties in accessing and engaging this population and the fact that this study was able to access this population and collect data on both subjective and clinical oral health measures and attain a good response rate is novel.

Future implications

This study is the first known study that is comparable with local and national oral health needs assessment for the general population, and therefore provides the opportunity to directly compare the oral health needs of patients with severe mental illness and how this may differ from the general population. An examiner who was trained and calibrated to undertake the National Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 undertook data collection and the methodology was the same for both surveys, which increases the reliability of the examinations. This study could act as a guide for future studies and needs assessments in hard to access groups and the mental health community. However, if repeated, the study should include sampling of medical practices as this may be less stigmatising for the participants than the clinics. Also, translation services should be arranged to ensure comprehensive sampling and reduce any inequalities that may have arisen in this study.

It is clear that the population with severe mental illness have unhealthier lifestyle factors such as smoking, more caries, a greater number of missing teeth and lower dental attendance. An upstream approach to the management of these issues could be developed whereby specific oral health promotion activities are implemented to improve oral care, diet, reduce smoking and increase dental attendance. This should be recommended in both community and institutionalised care, as oral health in both settings requires consideration. In this project, the mental health team staff were vital and one possible mechanism that could be researched is the use of community mental health team staff in delivering oral health promotion messages. Links between community mental health trusts and dental services should be strengthened to provide support and immediate access to dental care for people with severe mental illness. As people with severe mental illness may not access services routinely and are more likely to attend for urgent care, oral assessments could be undertaken at psychiatric sites to overcome issues in attendance and anxiety.

Overall, this survey found that oral health has a greater impact on patients with severe mental illness being treated in the community setting, and their oral health is poorer than the national adult population. Despite the limitations of this work, there are implications for potential service development and future research should also consider the causes that relate to the poorer oral health in this population. Consideration should be given to an upstream approach to improving oral health in this population.

References

Almomani F, Williams K, Catley D, Brown C . Effects of an oral health promotion program in people with mental illness. J Dent Res 2009; 88: 648–652.

Andrews G, Slade T, Peters L . Classification in psychiatry: ICD-10 versus DSM-IV. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174: 3–5.

Osborn D P . The poor physical health of people with mental illness. West J Med 2001; 175: 329–332.

Friedli L, Parsonage M, (2007) “Building an economic case for mental health promotion: part I”, Journal of Public Mental Health, Vol. 6 Iss: 3, pp.14–23.

World Health Organization. Mental health fact file. WHO, 2010. Online article available at http://www.who.int/mental_health/en/ (accessed October 2012).

Barr W . Characteristics of severely mentally ill patients in and out of contact with community mental health services. J Adv Nurs 2000; 31: 1189–1198.

Harnois G, Gabriel P . Mental health and work: impact, issues and good practices, Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000.

Cormac I, Jenkins P . Understanding the importance of oral health in psychiatric patients. Advances in psychiatric treatment 1999. 5: 53–60.

Atkinson M, Zibin S, Chuang H . Characterizing quality of life among patients with chronic mental illness: a critical examination of the self-report methodology. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 99–105.

Slade G D, Spencer A J . Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health 1994; 11: 3–11.

Locker D, Allen P F . Developing short-form measures of oral health-related quality of life. J Public Health Dent 2002; 62: 13–20.

Office for National Statistics. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. London: ONS, 2011.

Hughes J R, Frances R J . How to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Psychiatr Serv 1995; 46: 435–436.

Menezes P R, Johnson S, Thornicroft G et al. Drug and alcohol problems among individuals with severe mental illness in south London. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168: 612–619.

Ponizovsky A M, Zusman S P, Dekel D et al. Effect of implementing dental services in Israeli psychiatric hospitals on the oral and dental health of inpatients. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60: 799–803.

Dickerson F B, McNary S W, Brown C H, Kreyenbuhl J, Goldberg R W, Dixon L B . Somatic healthcare utilization among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. Med Care 2003; 41: 560–570.

Farnam C R, Zipple A M, Tyrrell W, Chittinanda P . Health status risk factors of people with severe and persistent mental illness. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 1999; 37: 16–21.

Kumar M, Chandu G N, Shafiulla M D . Oral health status and treatment needs in institutionalized psychiatric patients: one year descriptive cross sectional study. Indian J Dent Res 2006; 17: 171–177.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, R., Gamboa, A. Prevalence of oral diseases and oral-health-related quality of life in people with severe mental illness undertaking community-based psychiatric care. Br Dent J 213, E16 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.989

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.989

This article is cited by

-

Detecting high-risk neighborhoods and socioeconomic determinants for common oral diseases in Germany

BMC Oral Health (2024)

-

Association between high psychological distress and poor oral health-related quality of life (OHQoL) in Japanese community-dwelling people: the Nagasaki Islands Study

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2020)

-

Oral health interventions for people living with mental disorders: protocol for a realist systematic review

International Journal of Mental Health Systems (2020)

-

Correction

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Status and perception of oral health in 6–17-year-old psychiatric inpatients—randomized controlled trial

Clinical Oral Investigations (2017)