Key Points

-

Highlights that, in general, fixed rather than removable prostheses are increasingly preferred by patients.

-

Stresses that in all instances a panoramic radiograph is required, which may reveal retained roots and other conditions likely to cause dental treatment problems.

-

Determines that where no compelling reason can be found, no replacement of the missing teeth is the preferred treatment option, particularly in older adults.

Abstract

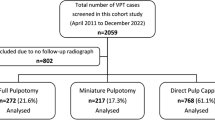

Although more people are retaining increasing numbers of their natural teeth into older ages, approximately 30-40% of persons over the age of 75 years in Western countries are edentulous. The causes and significance of tooth loss vary widely among individuals and cultures, and missing teeth may be replaced by a variety of means for functional, social and psychological reasons, rather than for significant physical health benefits. Therefore, it is essential to determine what the loss of teeth means to patients and what their expectations are for the outcomes following tooth replacement by various methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

When there are compelling reasons for tooth replacement, and when there are no financial or other constraints, then fixed rather than removable prostheses are increasingly preferred by patients. For both partially dentate and edentulous patients, either initial restorative or other pre-prosthetic preparatory treatments are often required before a definitive prosthesis is fabricated for the clinical option chosen in consultation with the patient. The successful outcome of complete dentures in particular is determined by many patient, dentist and dental technician factors.boxed-text

Successive national oral health surveys from several Western countries show an increasing number of natural teeth retained in their increasingly elderly populations. However, the average number of teeth present decreases with age, in particular after the age of approximately 55-65 years, when around 8-10 permanent teeth (usually posterior) are missing. Although fewer persons are now edentulous, the prevalence increases markedly in those aged 75 years or older to approximately 30-40%. Though only approximately 15% of persons wear dentures, the prevalence also increases markedly in those aged 75 years or older to around 60%. In addition, many of these elderly persons require either new, or repairs to existing, removable complete and partial dentures. For many reasons, some 20% of all dentures are not usually worn by patients. The future need for prosthodontic services will increase substantially in tandem with ageing populations.

Despite improvements in oral health, as shown by various surveys, there are large differences in the levels of oral disease present among populations from different socioeconomic groups, and between institutionalised and non-institutionalised populations. The increased retention of teeth and the replacement of missing teeth results in an increased need for preventive, periodontal and restorative dental services, which may not be available to, or affordable by, many disadvantaged persons. Providing dental care for the elderly is more complex than providing dental care for younger patients. Deleterious cumulative effects from dental diseases and previous dental treatments, combined with increasing physical and mental health problems (and associated polypharmacy-induced problems) that may be associated with ageing, are challenging factors for satisfactory treatment planning and patient management. In addition, the increased demands and expectations of many older patients for various aesthetic restorative treatments that have been promoted by media sources are not always realistic.

Causes and significance of missing teeth

The reasons for the teeth being missing should be determined as part of the previous dental history. Usually, teeth are missing because of extractions caused by previous dental caries and advanced periodontal disease. Unfortunately, in many instances the remaining teeth and potential tooth abutments for prostheses are compromised by the same dental diseases. Some teeth may not be present following acute trauma, or because they are either unerupted or impacted. In other instances, teeth may not be present in the mouth because they are congenitally absent. In all instances, a panoramic radiograph is required, which may reveal retained roots and other conditions likely to cause dental treatment problems.

Increasingly, tooth loss from dental caries is associated with hyposalivation caused by many prescription and non-prescription drugs, and by salivary gland damage. Apart from increased dental caries that typically involves the cervical and cusp tip/incisal edge regions and exposed roots of the teeth, severe hyposalivation also may result in:

-

Dry, reddened painful oral mucosa and cracked lips, angular cheilitis, atrophy of the tongue's filiform papillae and gingivitis

-

Candidosis, oesophagitis, heartburn and oral malodour (halitosis)

-

Impaired speech, chewing, swallowing, taste and smell

-

Impaired denture wearing and denture-induced stomatitis.

Affected persons may aggravate their existing poor oral and general health by resorting to cariogenic and acidic foods, beverages, chewing gums and confectionary. Their quality of life may be very poor, leading to chronic depression with potential increased suppression of saliva production.

The significance of loss of teeth varies greatly among individuals. A single missing second molar tooth may be a significant concern for one person, while another person may regard being edentulous as inevitable and merely an inconvenience. Others believe that all of their dental problems will be resolved most effectively by the extraction of all of their teeth. In years past, it was not unusual for young adults to have all their teeth extracted before marriage or before commencing employment in some occupations. In some instances, the removal of a previously sound maxillary central incisor tooth is evidence of adult initiation and acceptance into a specific population's culture, and the missing tooth is not replaced. However, the absence or loss of teeth in some persons may have severe social and professional ramifications, and be strongly associated psychologically with the loss of self-esteem and even the adverse consequences of ageing.

Individuals also place a differing emphasis on the relative importance of masticatory function, phonetics and appearance. For example, bilateral mandibular free-end saddle (denture base) removable partial dentures may be worn only to improve appearance, and be removed to allow better and more comfortable chewing. Many patients are more concerned about the adverse effect on their appearance caused by a single missing maxillary anterior tooth than about any possible adverse effects caused by many missing posterior teeth. Following the loss of (usually molar) teeth in younger patients, concerns may occasionally be expressed about subsequent problems caused by the migration and tipping of teeth adjacent to the extraction sites, and by the supra-eruption of unopposed teeth.

Moderate loss of posterior teeth may or may not result in a significant decrease in maximum bite force. There is a very large overlapping range of maximum bite forces between persons with reduced numbers of posterior teeth and those with complete natural dentitions. The gender and frailty of persons is probably of greater significance for maximum bite force than merely the possession of a certain number of natural teeth. Maximum bite forces should not be equated with chewing efficiency, because chewing occurs at much lower forces. Chewing efficiency is related to the number and types of natural teeth present, and artificial teeth and prostheses present, as well as to the types of food consumed and amount of saliva produced.

Importantly, the significance of the missing teeth to the patient, and to the dental health of the patient, must be determined before tooth replacement is undertaken. In most instances, in most patients, not all missing teeth require replacement either to avoid adverse social, professional, psychological and dental health problems, or to allow adequate mastication, phonetics and appearance. It is debatable whether, apart from quality-of-life concerns, that the replacement of congenitally absent or extracted teeth significantly benefits patients from a physical medical health perspective.

The partially dentate patient

Treatment options for missing teeth should be preceded by a systematic gathering of information concerning the patient's medical, dental and social/family histories, followed by a thorough extraoral and intraoral clinical examination. Before a treatment decision is made to replace missing teeth, the reasons usually stated for such a decision should be examined. All too often, it is automatically assumed that all missing teeth have to be replaced, often for ill-defined and unconfirmed reasons.

Do tooth extractions lead to occlusal instability and the worsening of the periodontal health of adjacent teeth? Though no substantial evidence base is available, clinical experience indicates the tooth loss in middle-aged and older persons does not lead to significant tooth migration and tipping of posterior teeth adjacent to the extraction sites, or to significant supra-eruption of posterior teeth opposite the extraction sites. In most instances, long-term tooth movements in one study were ≤1.0 mm, and largely stable after two years. Occlusal instability following tooth extraction is more likely following permanent molar extractions in adolescents and young adults. Clinical advantage may even be taken of the rapid mesial migration of erupting permanent molar teeth in children. When the extractions of first or second permanent molar teeth are required, then these extractions may be timed to allow tooth replacement (repositioning) by the rapid mesial migration of erupting second or third molar teeth, respectively.

How many pairs of occluding teeth are needed for adequate function and appearance? A full complement of 32 or even 28 permanent teeth is not required for the masticatory system to function adequately. The concept of the 'shortened dental arch' is well established. In older persons, ten pairs of occluding anterior and premolar teeth meet the functional and aesthetic demands of most patients, with two pairs of molars required for the improved chewing of very hard foods. Six to eight pairs only of occluding anterior and premolar teeth may possibly lead to occlusal instability, but the evidence is weak.

Do fixed and removable partial dentures lead to better oral health and improved survival of the remaining teeth? Adjacent tooth survivals after ten years were high and not significantly different for either untreated extraction spaces or tooth replacements by fixed prostheses. However, the long-term survivals of teeth adjacent to extraction spaces were significantly lower where removable partial dentures were used. Failed teeth had more restorative, endodontic and periodontal treatments than surviving teeth. Many studies have demonstrated the adverse effects of removable partial dentures on the abutment teeth in particular. Adverse effects on the oral soft tissues and alveolar bone also may be present.

In all instances where no compelling reason can be found, and particularly in older adults, no replacement of the missing teeth is the preferred treatment option. The advantages of not replacing every missing tooth include, less:

-

Complex and costly dental treatments required

-

Iatrogenic tissue damage and resulting problems

-

Protracted treatments, treatment stress and discomfort

-

Subsequent dental disease and problems with less-than-ideal abutment teeth

-

Maintenance and replacement of defective prostheses

-

Risk of litigation from failed treatments and dissatisfied patients.

When natural teeth are being considered as potential abutments for either fixed or removable prostheses to replace missing teeth, several factors need to be considered. Investigations include radiographic, pulp, dental hard tissue and periodontal tissue health, and occlusal evaluations. Ideally:

-

The teeth are structurally sound, with satisfactory appearance and crown forms

-

The teeth are in good alignment and position, requiring neither orthodontic therapy nor complex designs for the prostheses

-

The previous restorations and endodontic treatments are satisfactory

-

The abutment tooth roots and supporting alveolar bone are functionally adequate

-

The alveolar bone of the edentulous ridge between, or distal to, the abutment teeth is adequate in quantity and quality

-

The soft tissue of the edentulous ridge is satisfactory in quantity and quality.

An assessment also needs to be made of the space available for the prosthesis, after mounting diagnostic casts on a semi-adjustable articulator. Mesio-distal spaces between the abutment teeth may be too small or too large for the artificial tooth pontic(s)/dental implant(s) relative to the sizes and positions of the natural teeth (Fig. 1).

In some instances, orthodontic tooth repositioning and/or judicious contouring of natural tooth crowns using resin composite may be indicated. Isolated pier abutment teeth and their prosthodontic retainers are prone to failures caused by functional overloading. Fixed partial dentures should have a semi-rigid connector placed at the distal surface of the central pier abutment retainer. When planning for removable partial dentures, consideration should be given to elective endodontic therapy and de-coronation of the pier tooth, using the root to support the denture.

Insufficient inter-occlusal vertical space may require an increase in the occlusal vertical dimension. This may be achieved by placing a Dahl bite-raising appliance that only occludes with selected teeth, thus allowing the separated non-occluding teeth to erupt further passively (Figs 2 and 3). Instead of first using a Dahl appliance, permanent restorations (usually either resin composite build-ups, artificial crowns or cast onlays), employing the same principle may be placed immediately. Alternatively, a cast alloy removable onlay denture may be fabricated. Often, the abutment teeth, or proposed dental implants, may be over-tilted facio-lingually. This usually involves the lingual tilting of mandibular molar and premolar teeth, and the facial tilting of maxillary dental implants that are constrained by the form of the alveolar ridge.

Fixed partial dentures (bridges)

Despite their higher costs, fixed prostheses, including dental implant superstructures, are perceived by patients to be preferable to removable partial dentures for replacing missing teeth. Many removable partial dentures are not worn, in particular mandibular posterior free-end saddle appliances and those that do not improve the appearance of patients. The fit, retention, support and stability of acrylic resin removable partial dentures are often unsatisfactory. Relative advantages and disadvantages for fixed and removable partial dentures are given in Table 1. Often, a short-span fixed prosthesis or a dental implant can be used to replace a single missing anterior or premolar tooth, and a removable partial denture of simplified design can then be used to replace multiple missing posterior teeth in the same patient. Frequently, however, following the placement of the fixed prosthesis, the patient decides that the additional removable prosthesis is not really necessary (Fig. 4).

There have been several reports of numerous designs proposed by different practitioners for both fixed and removable prostheses to replace the same missing teeth. Increasingly, with the outsourcing of laboratory work and the reduction in undergraduate prosthodontic clinical experience, designs and materials for prostheses are no longer being prescribed by dentists. There have also been differing opinions on using either dental implants, or fixed and removable prostheses to replace single missing teeth. The choice is obviously influenced by numerous patient-related and dentist-related factors. Although there is no perfect design for a prosthesis, some designs are more appropriate than others for patients. Whatever treatment mode is selected, it should minimise the long-term biological hard and soft tissue costs to the patient. Simplified designs for the prostheses are required to minimise damage to teeth and soft tissues.

Missing single anterior and premolar teeth may be replaced effectively using short-span cantilevered fixed prostheses. From meta-analysis, conventional cantilevered fixed prostheses of all designs had a reported ten-year survival of 82%. This figure would undoubtedly be higher for short-span conventional mesially-cantilevered prostheses placed in low-stress situations.

Resin-bonded single tooth replacements using cantilevered metal or winged ceramic retainers have reported five-year survivals from 83-92%. These percentages were much higher than those for resin-bonded fixed-fixed designs using the same two retainer materials (Figs 5 and 6). The earlier metal framework designs for resinbonded prostheses resulted in unacceptable failure rates. Since then, the importance of both improved retentive and resistant tooth preparation and framework designs has been realised. Resin-bonded cantilevered anterior single-tooth replacements require two diagonally opposite axial retention grooves placed in the abutment tooth, while similar posterior single-tooth replacements require that the two diagonally opposite axial grooves in the abutment tooth be joined occlusally by a D-shaped strut. Cantilevered designs include the advantages of simpler single-tooth preparations and easier insertion of prostheses, and being less expensive than conventional fixed-fixed prostheses.

Conventional fixed-fixed and fixed-movable partial denture designs and, in selected situations, resin-bonded fixed-movable partial denture designs may be suitable for longer-span edentulous anterior and posterior sites (Figs 7 and 8). The retainer designs should allow for the later possible loss of abutment teeth having a questionable long-term prognosis, and for the possibility of the patient later requiring dental implants or a removable partial denture. In this latter situation, the appropriate fixed partial denture crown retainer should include an occlusal rest seat, a lingual guide plane, and have the facial surface contoured to allow for future adequate denture clasp retention, if so required.

To reduce the stresses arising from occlusal forces, the partial denture in the patient in Fig. 7 incorporated a semi-rigid connector housed within the first premolar pontic

The survival rates of vital abutment teeth are usually higher than those for non-vital endodontically treated abutment teeth, for long-span fixed prostheses in particular. The survival rates of long-span fixed partial dentures also are usually lower than those for short-span prostheses. A meta-analysis of six studies of fixed partial dentures inserted on teeth with severely reduced but healthy periodontal tissue support yielded survivals of 93% after ten years, which compared favourably with similar prostheses placed on non-periodontally compromised tooth abutments.

Removable partial dentures

These are usually considered when multiple missing teeth, long edentulous spans, unsuitable abutment teeth that also may include sound abutment teeth in young patients, alveolar ridge deficiencies (because socket preservation grafting was not carried out at the time of tooth extraction), and financial costs preclude alternative fixed prostheses. However, missing tooth spaces with a single central pier abutment tooth result in more complex metal framework designs and high stresses on the pier abutment (Figs 9, 10, 11, 12).

Tooth-supported removable partial dentures are generally preferable to those that are soft tissue-borne or mucosal-supported, and removable partial dentures with cast alloy frameworks are generally preferable to acrylic resin-based partial dentures. The latter are usually entirely mucosal-borne resulting, in the mandible in particular, in excessive alveolar bone resorption and gingival recession affecting adjacent teeth. Cast alloy frames using base-metal alloys require long cast clasp arms (∼14 mm) engaging small retentive undercuts (∼0.25 mm) to prevent their permanent deformation and fatigue fracture caused by constant flexure when placing and removing the partial denture. Therefore, long gingivally-approaching I-bar clasps are required for canine and premolar abutment teeth, especially when using stiff cobalt-chromium alloys (Fig. 13).

Wrought stainless steel wire clasps, which have greater flexibility, may be indicated for short clasp arms engaging larger undercuts. Simplified 'biologically friendly' removable partial denture designs are preferred, which attempt to minimise plaque retention and contact of the partial denture with tooth and gingival tissues.

Removable partial dentures require regular patient recalls and high maintenance, with the need for adjustments and the repair of denture fractures and of tooth abutments a common occurrence. Problems may include tooth and/or mucosal pain or discomfort, looseness, difficulties in seating, problems with chewing and speech, and poor appearance of the denture. Despite the use of simple removable partial denture designs and regular recalls, their survival rate in one large study was only 50% after ten years.

Osseointegrated dental implants

The use of dental implants, in particular single-tooth implants, continues to increase. Some 25% of practitioners now provide this treatment in developed countries. An extensive literature has documented the high long-term clinical survival rates of osseointegrated dental implants supporting single-tooth crowns, fixed partial and fixed complete dentures, and implant-supported removable complete overdentures in selected patients. When they are indicated, dental implants offer increased comfort, retention and stability for mandibular complete dentures and overdentures in particular (Figs 14, 15, 16).

Panoramic radiograph of implant-retained fixed lower complete denture, from the patient in Fig. 14

Frontal view of removable upper complete denture and fixed lower complete denture, from the patient in Fig. 14

However, implant-supported fixed partial dentures do not appear to provide a significant functional improvement compared to tooth-supported removable partial dentures. Considerable ingenuity has been used to overcome the problems caused for implant placement from inadequate bone support and the anatomical structures present at some sites. But, several of the surgical procedures required are both traumatic and expensive, and are not accepted or afforded by many patients.

Though the long-term survival (retention) of dental implants is very high, the long-term survival of the prosthetic superstructures is somewhat lower. A meta-analysis of survival studies reported 93% for implants and 87% for superstructures after ten years. However, 39% of patients had superstructure complications, usually minor, and 9% had peri-implantitis and soft tissue complications needing treatments after only five years. Another study of single-tooth implant survivals found 97% for implants and 83% for superstructures after four years. At this time, approximately 20% of patients had mechanical superstructure complications needing some form of treatment. In edentulous jaws, over five years, superstructure repairs were found to be high when implant-supported prostheses were opposed by fixed prostheses of similar design, but low where the implant-supported prostheses were opposed by removable complete dentures. High maintenance has also been reported for implant-supported removable complete overdentures. These studies all point to frequent long-term maintenance problems and costs associated with implant superstructures in particular. The clinical success rates of implants are usually not reported, but are lower than the actual high survival (retention) rates reported, which often pertain to relatively small long-term sample sizes. In addition, implant failures before functional loading may be excluded from the survival analyses. Thus, excellent results may be recorded despite such occasional failures, the presence of soft tissue complications and high marginal bone losses around the implants, and technical complications requiring treatment.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of long-term controlled clinical trials to determine the relative cost-effectiveness of replacing even single missing teeth. Such trials are required to establish the relative cost-effectiveness of the single implant-supported crown, the cantilevered two-unit fixed partial denture (both conventional and resin-bonded), and the endodontically treated and restored tooth. The single implant option is possibly the least cost-effective long-term treatment choice, though there may be little short-term cost difference between the single-tooth implant and the more extensive conventional three-unit fixed partial denture in some practices. Financial costs should be balanced against biological costs, as the use of dental implants avoids the problems of dental caries, tooth erosion and the preparation of abutments in sound tooth structure, as well as excessive alveolar ridge resorption following tooth extractions.

The unattractive display of clasps on removable partial dentures and of metal retainers in resin-bonded fixed partial dentures may be avoided. Dental implants may also act as substitutes for unsatisfactory tooth abutments, and may be preferable when there are long edentulous spans present (Fig. 17). Although there are no significant differences in survival between restored endodontically treated teeth and single-tooth implants, there is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that increasing numbers of 'endodontically questionable teeth' are being extracted unnecessarily, and being replaced by costly dental implants to then preserve the remaining alveolar bone.

Careful treatment planning involving physical and psychological health factors, and local anatomical and other oral factors, is required for successful dental implant-supported prostheses. There are many biophysical differences between a natural tooth and an endosseous dental implant, requiring careful assessments of occlusal loading of implants and the design of the prosthetic superstructures. During the childhood period of rapid jaw development, apart from the anterior mandibular region, the placement of dental implants in the jaws is not advisable because the implants behave as ankylosed teeth. As part of the treatment planning process, sophisticated three-dimensional radiographic imaging and associated treatment planning software are promoted to achieve the optimum intraosseous placement of various sizes and forms of dental implants. Cone beam computed tomography is rapidly becoming the required diagnostic and treatment planning method.

Initial and definitive treatments

Extensive and expensive comprehensive definitive treatments to replace missing teeth should be deferred until the initial emergency, active disease control, preventive and restorative dental treatments required are completed and the results evaluated. Teeth are often missing because of untreated previous dental diseases arising from dental neglect. In many instances, the remaining teeth show evidence of similar untreated dental diseases such as dental caries and periodontal disease, and untreated conditions such as tooth surface loss, and unsatisfactory restorations and root canal therapy. Decisions have to be made as to which teeth are likely to have a poor long-term prognosis, which teeth are non-restorable, and which teeth are critical to maintain as possible abutments for prostheses.

Unfortunately, consistency in treatment decisions by individual practitioners is lacking, and there also is ample evidence of the inability of different practitioners to agree on the most appropriate treatment plan for a particular patient. However, although there are few clinical prosthodontic guidelines that are strongly evidence-based, the practitioner should have an established template on which to base short-term and possible long-term treatment plans that are appropriate for each patient (Fig. 18).

Missing reeth – a guide to treatment options. pp 12, Fig. 2. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2003. Copyright Elsevier 2008, adapted with permission)

First, the information obtained from the histories and clinical examination should broadly determine, after careful reflection on the risk-benefits of each strategy, whether therapeutic treatment is required or not. And, if treatment is required, whether the remaining dentition should either be restored or the patient rendered essentially edentulous in one or both jaws. (Transitional therapy involving a training denture may be considered when, in the reasonably near future, becoming edentulous is inevitable). Next, the clinical options for replacing missing teeth by using dental implants, traditional fixed and removable partial or complete dentures (and combinations thereof) are determined by many patient-related and dentist-related factors. Many of these general considerations or factors have been mentioned previously (parts one and six). However, several additional factors are pertinent to the replacement of missing teeth in the partially dentate patient.

Patient factors

Numerous periodontal pockets, restorations, endodontic therapies and extensive tooth surface loss affecting the remaining teeth of young adults are more clinically significant than similar conditions present in older persons. Smoking is a significant factor for adversely affecting periodontal health and osseointegration of dental implants. Occasionally, minor occlusal adjustments are required before tooth preparation, and minor orthodontic tooth repositioning may improve the periodontal health and the spacing and alignment of abutment teeth or teeth adjacent to proposed dental implant sites. Orthodontic tooth repositioning is generally faster in younger than in older persons. The larger pulp chambers present in younger persons may preclude the provision of anterior all-ceramic crowns.

Dentist and technician factors

Of critical importance are the abilities of the dental practitioner and laboratory technician competently to provide the treatment and prostheses required, and to maintain and repair the prostheses. Good teamwork, involving good communication and planning, is important to avoid problems in the fabrication of prostheses and the ordering of parts and laboratory analogues. Detailed laboratory instructions should accompany the disinfected high-quality clinical records. Semi-adjustable articulators should be stipulated as being routine for fabricating most prostheses. Appropriate magnification is essential for most operative and laboratory procedures. A careful analysis of the occlusion and careful surveying of mounted diagnostic casts are required as part of the treatment planning for all fixed and removable partial dentures, and dental implants. A diagnostic wax-up of the proposed restorative changes, and intraoral photographs, should form part of the treatment planning and patient discussion processes.

Monitoring of oral health and treatments

Monitoring of oral health and the condition of prostheses, together with the maintenance of a preventive programme is required for all patients. Monitoring is a proactive recorded process, which should not be confused with doing nothing over long periods, as with instances of active periodontal disease and tooth erosion. Basic dental treatments are usually required before the subsequent provision of a prosthesis. In many instances, initial preparatory treatments may be quite extensive and require a period of monitoring after their completion before any prosthesis is fabricated.

Frequently, the so-called 'ideal' treatment plan is replaced by the most practical or realistic 'optimal' treatment plan. Most dental problems have more than one treatment option or solution, and each solution has its own treatment planning implications with associated advantages and disadvantages, including the time taken and financial costs. A comprehensive definitive treatment plan may only evolve after a protracted period of initial priority treatments and consultations during which time the oral health condition and attitude of the patient are monitored and evaluated. Because comprehensive dental treatments are seldom 'final', being subject to continued wear and tear, with the need for ongoing reviews and maintenance, these latter requirements must form part of the dental treatment aims or goals agreed to by the patient.

The edentulous patient

The acceptance by patients of complete dentures largely depends on their being able to make the necessary functional, social and psychological adaptations required for successful denture wearing. Otherwise, even the highest clinical and technical skills employed in the provision of the dentures may result in disappointment. Therefore, it is essential to determine whether the patient's expectations of denture wearing are realistic or not. The patient who brings a collection of 'unsatisfactory' complete dentures to their first appointment is a real challenge for any practitioner. Most people in developed countries now lose all of their teeth at much older ages than previously, and consequently they often have concomitant medical and other problems. For these reasons, the information required for adequate diagnosis and treatment of edentulous patients is somewhat different from that pertaining to younger dentate patients.

Chief complaint or reason for attendance

This should be recorded in the patient's own words, but may require clarification. A denture that 'does not fit' may be loose, oversized, or have very worn artificial teeth. It is essential to establish a rapport with the patient at this time by demonstrating, both verbally and by using appropriate body language, genuine concern and interest in the patient's problem(s).

Previous dental history

This should determine when and why the natural teeth were lost, and how the patient feels about this loss. Teeth lost because of advanced periodontal disease in older persons or from dental caries at a young age may result in poor residual alveolar ridge form. Patients who regret having had all of their teeth extracted, and who find this loss very difficult to accept, may prove difficult to treat successfully with conventional dentures. Dental implant-supported fixed complete dentures may be an alternative treatment option, where the psychological benefits may equal the functional benefits. It is also important to find out how the patient has managed with any previous dentures that may have been made. A history of wearing dentures that were previously satisfactory is likely to result in fewer problems than a history of several unsuccessful attempts at wearing dentures. If the previous dentures were successful, then they should be used as a template for replacement.

Previous medical history

Many of the elderly patients requiring complete dentures will be under medical treatment and taking prescribed drugs and other medications for numerous physical and psychological conditions, some being serious illnesses requiring consultation with the patient's physician. Various medications and illnesses may result in a dry mouth which, together with psychological problems such as depression, and problems associated with mental impairment and reduced neuromuscular coordination, will adversely affect successful denture wearing. The elderly and frail in particular may have a reduced tolerance, adaptability and neuromuscular control for the successful management of new dentures. These persons also may have problems with their eyesight and hearing, and have difficulties in getting into and out of the dental chair, and even in physically accessing the dental practice.

Family and social history

Consideration should be given to the social and environmental aspects of patients. Some patients may attend with a relative or friend for support and to offer an opinion at the trial denture stage before final fabrication. Some prosthodontic norms might produce dentures that restore facial contours, but these may result in social embarrassment owing to relatives of older patients being accustomed to the appearance of the patient wearing worn dentures. Again, some patients perceive that their partners are unaware of their denture-wearing status and are thus disinclined to have radical changes to their appearance.

This may be counterbalanced with the patient requesting that replacement dentures eliminate post-extraction and ageing changes. Old photographs are frequently presented with the request to duplicate the appearance of the natural teeth in the new dentures. In all cases, the clinician should endeavour to produce an agreed appearance that will not cause social embarrassment. Patients also may have unrealistic expectations of the types of foods that they can manage with complete dentures, such as biting hard apples. Softer foods and small portions of harder foods comprising an adequate and balanced nutritional diet should be able to be eaten satisfactorily.

Extraoral examination

Apart from an initial assessment of the general physical condition and dentofacial form of each patient, specific features of the edentulous patient should be evaluated. These include:

-

Whether or not an obvious skeletal malrelationship is present between the maxillary and mandibular jaws that may influence the positioning of teeth or denture stability

-

Whether the vertical facial dimension indicates either overclosure (a reduced occlusal vertical dimension) or an excessive occlusal vertical dimension associated with the existing dentures

-

Bruising of the bridge of the nose associated with the wearing of spectacles, which may suggest impaired tissue fragility

-

The presence of angular cheilitis, which may indicate a maxillary denture-induced stomatitis associated with poor denture hygiene and candidosis. Occasionally, there may be poorly controlled diabetes or an associated anaemia and nutritional deficiency

-

Reduced tonus of the facial tissues and masticatory muscles, and whether a normal range of pain-free, smooth excursive movements of the mandible can be made. Patients may request that their new dentures incorporate additional bulk to 'plump out' the soft tissues of their lips and cheeks

-

Uncontrolled muscular activity, for example, Parkinsonial dyskinaesia.

Difficulties in pronouncing certain words and letters, and lisping, or posturing of the mandible and tongue or lips during speaking.

Intraoral examination

A thorough examination is required to assess the health of the oral mucosa, the mobility and size of the tongue that may enlarge following the loss of teeth, the size and form of the edentulous ridges, the relationship of the maxillary and mandibular residual alveolar ridges to each other, and the quantity and quality of the saliva. The soft tissues should be inspected carefully for any suspicious lesions, including those that may be potentially malignant, and palpated gently for regions of tenderness. Appropriate consultations are required when suspicious lesions are detected. The mucosa may show evidence of damage from the existing dentures, such as denture-induced stomatitis/papillary hyperplasia (denture sore mouth), and mucosal ulceration/hyperplasia from over-extended flanges and cheek biting. A panoramic radiograph may be indicated as part of the clinical examination, as it may reveal the presence of unerupted teeth and retained root fragments.

It is usually assumed that the support, retention and stability of complete dentures are related directly to the potential denture-bearing areas, although many studies have failed to show a clear relationship between denture-bearing anatomical features and patient satisfaction with their dentures. However, the provision of pain-free and comfortably fitting, well-functioning dentures with a socially acceptable appearance contributes much to the satisfaction of patients. The following conditions may adversely affect the support, retention and stability of both removable partial and complete dentures:

-

Deficiencies in the quantity and quality of saliva, which may be associated with poor denture retention, traumatic micro-abrasions, difficulties in eating and speaking, altered taste perception, candidosis and denture-induced stomatitis, and 'burning mouth syndrome' (Fig. 19). The latter, when affecting the palatal mucosa, is significantly associated with wearing complete upper dentures and a dry mouth

-

Retained roots and partially erupted teeth, which require assessment and possibly their removal

-

Bony lumps and prominences (exostoses and tori), which may require relief on the master casts (Fig. 20)

-

Enlarged maxillary tuberosities, which may require a resilient denture base in these areas or, in extreme cases, surgical reduction to provide sufficient inter-arch clearance provided thatthe maxillary antra are not encroached on (Fig. 20)

-

Undercuts, which may dictate and limit denture extension or the path of insertion, or require a resilient denture base in these areas (Fig. 21)

-

Areas of the mouth that are tender to palpation, such as over the superficial inferior dental and mental nerves, which may require relief on the master cast

-

Severe alveolar ridge resorption and atrophic mucosal covering, which may make it difficult or impossible to prescribe satisfactory complete dentures. A thin body of the mandible is also prone to fracture from even minor trauma in the elderly

-

Displaceable tissue such as fibrous (flabby) ridges, and denture flange ulcers and/or irritation hyperplasias, which may require surgical removal or the use of an appropriate selective pressure impression technique (Fig. 22)

-

Frenae or muscle attachments close to the crest of the edentulous alveolar ridge, which may interfere with the peripheral extension of the complete denture and lead to denture instability. Midline denture fractures are more probable when the upper denture with a deep frenal notch opposes natural teeth, because of the higher occlusal forces that are possible. Where the upper complete denture opposes remaining natural mandibular anterior teeth only, focused occlusal forces may result in the occurrence of a flabby anterior maxillary ridge replacing alveolar bone lost from chronic trauma, this being the principal component of the so-called 'combination syndrome'.

Assessment of existing dentures

Though research has largely failed to demonstrate, conclusively, that denture quality affects patient satisfaction, and hence denture success, support remains for the important contribution that clinical and technical factors make towards successful treatment outcomes. Therefore, there are good reasons to examine carefully, existing and previous dentures both inside and outside the mouth.

Intraoral assessment

The complete dentures should be examined for:

-

Support (the property of the denture-bearing tissues that resists displacement of the denture towards these tissues). This involves maximum peripheral extension of the denture relative to anatomical landmarks such as the sulci, the junction of the hard and soft palates, the retromolar pads and the retromylohyoid fossae

-

Retention (the property of the denture-bearing and peri-denture tissues that resists displacement of the denture away from these tissues). Adequate retention depends mainly on close adaptation of the denture base to the tissues and a good peripheral border seal, in the presence of mucus secreted by palatal salivary glands for the upper denture. Continuous wearing of upper dentures damages the palatal glands resulting in less mucus. Retention of the lower denture is usually low, and may be assessed by placing a probe into the embrasure between the central incisors and attempting to lift the denture vertically

-

Stability (the property of the ridges, peri-dental musculature and the occlusal form of the dentures that resists displacement of the denture). Assessment requires careful observation of the denture while the examiner gently manipulates the lips and cheeks, or while the patient slowly opens his or her mouth. Displacement of the denture while these movements are being performed indicates overextension of the denture base and/or impingement onto muscle attachments. Equally important is to determine whether the denture peripheries are short of the sulcular reflection, thereby indicating underextension

-

Positioning of the artificial teeth relative to the levels and orientations of the occlusal and incisal planes, and tooth arrangement. These factors have implications for denture stability and patient comfort, and contribute to the overall appearance of the patient. Generally, the pattern of maxillary residual ridge resorption dictates that to restore support for the facial tissues, the artificial teeth should be set labial to the residual alveolar ridge, although the obvious exception is when immediate complete dentures are being provided. And, to enhance lower denture stability it is generally held that the central fossae of the artificial lower posterior teeth, along with the necks of the lower anterior teeth, should lie over the crest of the mandibular residual alveolar ridge

-

Occlusal contact relationships. These also have a bearing on denture stability and patient comfort. Simultaneous bilateral occlusal tooth contacts should occur at the retruded contact position of the jaws. The lower denture should be held in place by the dentist while the patient is performing this manoeuvre. In some patients, the manoeuvre may be facilitated by asking the patient to curl his or her tongue so that the tip contacts the posterior border of the upper denture, while at the same time elevating the mandible. Preferably, the patient is positioned semi-supine in the dental chair with the dentist seated behind the patient's head. It is important to observe the first point of occlusal contact as the mandible may deviate into a position of convenience – one that may not be reproducible, and which may contribute to skewing and instability of the lower denture in particular. The result may be pressure sore spots and mucosal ulcers. Also assess whether smooth articulatory movements are possible without causing the dentures to be displaced. Although many patients manage to chew effectively without their dentures having a balanced articulation, for some patients this may be a necessary requirement

-

Interocclusal distance. Clinical experience suggests that an appropriate amount of interocclusal distance or freeway space (FWS) is needed for patients to speak clearly and to chew effectively and comfortably with their dentures. It is determined by measuring the resting facial height (RFH) and the facial height with the teeth in occlusion – the occlusal vertical dimension (OVD). The FWS = RFH − OVD, being approximately 3-5 mm when the patient is sitting upright and looking straight ahead. The RFH is also known as the resting vertical dimension (RVD). For older patients in particular with poor residual alveolar ridges then 'for comfort, close the bite'

-

Appearance. This is very subjective but, at a basic level, the pattern of maxillary residual alveolar ridge resorption dictates that to restore support for the facial tissues, artificial teeth should be set labial to the residual ridge. The obvious exception is when immediate complete dentures are provided.

Extraoral assessment

The dentures should be rinsed, dried and examined under good lighting:

-

Denture hygiene should be assessed and, if necessary, reinforced to the patient by dye disclosure of plaque deposits. Poor cleaning may result in denture-induced stomatitis, oral malodour (halitosis) and angular chelitis. All patients should receive advice regarding how best to clean and maintain their acrylic resin complete dentures, such as placing them in dilute bleach for 20 minutes then storing in water overnight

-

Signs of excessive wear of the artificial teeth and denture bases may indicate dietary habits such as confections containing peppermint oil, and/or parafunctional and other habits such as pipe smoking. Any one of these factors will also affect the replacement dentures

-

Tooth size, shape, colour and arrangement should be noted, particularly regarding any comments the patient may make concerning these

-

The fitting or impression surfaces of the denture bases should be carefully examined for any signs of relief provided, as this may indicate problems previously encountered with the supporting tissues

-

Materials used in denture construction should be discussed, as there may be patient preferences such as characterisation, or problems that previously required the use of resilient denture base materials.

Enhancing complete denture function and comfort

The following suggestions are made:

-

Construct close-fitting, border-moulded (muscle-trimmed) dentures of optimum extension, having narrow cusped or cuspless posterior teeth placed in the neutral zone. The maxillary second molars or second premolars may be omitted

-

Avoid 'opening the bite' too much

-

Adjust the occlusion, then the denture bases when pressure spots are present

-

Consider 3 mm thick acrylic resin long-term soft liners for lower dentures

-

Maintain hydration and saliva production and stimulation

-

Use a saliva substitute, and a synthetic cream (upper denture) or moistened powder (lower denture) denture adhesive, if required

-

Keep the dentures clean and store them in water overnight

-

Brush the edentulous ridges and the dorsum of the tongue

-

Consider implant-supported fixed dentures and removable overdentures.

Treatment should only commence after a thorough assessment and analysis of each patient has been made. Diagnosis should aim to elicit those factors that are thought to contribute to the successful wearing of complete dentures. Only then can the patient be advised of their treatment choices and thus be in a position to give informed consent to treatment. Equally, should a practitioner be unsure about whether the expectations of the patient can be met, the appropriate course of action would be to withdraw from treatment and refer the patient to another, presumably more experienced, clinician.

References

Aquilino S A, Shugars D A, Bader J D, White B A . Ten-year survival rates of teeth adjacent to treated and untreated posterior bounded edentulous spaces. J Prosthet Dent 2001; 85: 455–460.

Atwood D A . Some clinical factors related to rate of resorption of residual ridges. J Prosthet Dent 2001; 86: 119–125.

Berkey D B, Berg R G, Ettinger R L, Mersel A, Mann J . The old-old dental patient. The challenge of clinical decision-making. J Am Dent Assoc 1996; 127: 321–332.

Botelho M . Design principles for cantilevered resin-bonded fixed partial dentures. Quintessence Int 2000; 31: 613–619.

Creugers N H, Kreulen C M, Snoek P A, de Kanter R J. A systematic review of single-tooth restorations supported by implants. J Dent 2000; 28: 209–217.

Fenlon M R, Sherriff M, Walter J D . Comparison of patients' appreciation of 500 complete dentures and clinical assessment of quality. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent 1999; 7: 11–14.

Gragg K L, Shugars D A, Bader J D, Elter J R, White B A . Movement of teeth adjacent to posterior bounded edentulous spaces. J Dent Res 2001; 80: 2021–2024.

Hakestam U, Söderfeldt B, Rydén O, Glantz E, Glantz P O . Dimensions of satisfaction among prosthodontic patients. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent 1997; 5: 111–117.

Iqbal M K, Kim S . A review of factors influencing treatment planning decisions of single-tooth implants versus preserving natural teeth with nonsurgical endodontic therapy. J Endod 2008; 34: 519–529.

Jivraj J, Chee W . Treatment planning in implant dentistry. London: British Dental Association, 2007.

Kayser A F . Limited treatment goals - shortened dental arches. Periodontol 2000 1994; 4: 7–14.

Kim Y, Oh T J, Misch C E, Wang H L . Occlusal considerations in implant therapy: clinical guidelines with biochemical rationale. Clin Oral Implants Res 2005; 16: 26–35.

McCord J F, Grant A A . A clinical guide to complete denture prosthodontics. London: British Dental Association, 2000.

McCord J F, Grant A A, Youngson C C, Watson R M, Davis D M . Missing teeth - a guide to treatment options. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2003.

Oruc S, Eraslan O, Tukay A, Atay A . Stress analysis of effects of nonrigid connectors on fixed partial dentures with pier abutments. J Prosthet Dent 2008; 99: 185–192.

Pjetursson B E, Tan K, Lang N P, Brägger U, Egger M, Zwahlen M . A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of fixed partial dentures (FPDs) after an observation period of at least five years. Clin Oral Implants Res 2004; 15: 667–676.

Rich B, Goldstein G R . New paradigms in prosthodontics treatment planning: a literature review. J Prosthet Dent 2002; 88: 208–214.

Sarita P T, Witter D J, Kreulen C M, Van't Hof M A, Creugers N H . Chewing ability of subjects with shortened dental arches. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003; 31: 328–334.

Torabinejad M, Goodacre C J . Endodontic or dental implant therapy. The factors affecting treatment planning. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137: 973–977.

van Dalen A, Feilzer A J, Kleverlaan C J . A literature review of two-unit cantilevered FPDs. Int J Prosthodont 2004; 17: 281–284.

Vermeulen A H, Keltjens H M, Van't Hof M A, Kayser A F . Ten-year evaluation of removable partial dentures: survival rates based on retreatment, not wearing and replacement. J Prosthet Dent 1996; 76: 267–272.

Wöstmann B, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Jepson N et al. Indications for removable partial dentures: a literature review. Int J Prosthodont 2005; 18: 139–145.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCord, F., Smales, R. Oral diagnosis and treatment planning: part 7. Treatment planning for missing teeth. Br Dent J 213, 341–351 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.889

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.889

This article is cited by

-

Unilateral removable partial dentures

British Dental Journal (2017)