Key Points

-

Children's evaluation of their own dental appearance is a very important factor in how they rate their oral health-related quality of life.

-

This association is of relevance when developing patient-reported outcome measures following treatments to improve dental aesthetics.

-

It highlights the dynamic nature of children's oral health-related quality of life and the impact of significant life events.

Abstract

Background A variety of inherited and acquired conditions affect the dentition. The aim of this research was to investigate the oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) of children in relation to the status of their permanent incisors, at a significant transitional stage in their childhood.

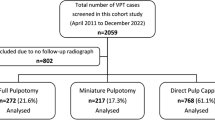

Method Two hundred and sixteen patients of the Charles Clifford Dental Hospital, Sheffield, aged between 10 and 11 years, were sent an OHRQoL questionnaire (CPQ11-14) three months before secondary school entry. Participants were categorised, according to clinical status, as having a visible dental difference (abnormal incisor aesthetics and/or orthodontic malocclusion) or no visible difference. Follow-up questionnaires were issued three months after secondary school entry to obtain repeat psychosocial data. Analysis of variance tests investigated the impact of clinical variables, self-reported satisfaction with dental appearance and gender on OHRQoL during educational transition.

Results Ninety-two children participated in the baseline study and 71 of these children completed the follow-up questionnaire (43% and 77% response rates, respectively). Visible dental differences and dissatisfaction with dental appearance were associated with worse OHRQoL at baseline and follow-up.

Conclusions Dental conditions which result in visible incisor differences are associated with higher levels of dissatisfaction with appearance and have potential to negatively impact on children's OHRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A wide spectrum of inherited and acquired conditions affect the human dentition and result in a variety of dental anomalies.1 Teeth may present with abnormalities of colour, morphology, position or number.2 A recent dental survey of British children3 found that 34% of 12-year-olds had visible enamel opacities affecting one or more of their permanent incisors, and 11% had sustained a traumatic injury to an anterior tooth, the majority of which remained untreated. A deviation from 'normal' incisor aesthetics may also be due to malocclusions such as severe crowding, rotation, spacing or proclination. Indeed, it has been estimated that 35% of British 12-year-olds require some form of orthodontic intervention on the basis of aesthetic and/or dental health needs.4

Appearance is central to social experience and interaction throughout life: how others react to facial differences can greatly impact on a child's sense of worth.5 There is some evidence that children with visible dental differences, such as traumatised incisors and incisor opacities, may be subject to negative social judgements and teasing by their peers about their social appearance.6,7,8 Individuals with developmental enamel defects, dento-alveolar trauma and malocclusions also appear less satisfied with their tooth colour/size and report worse oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) than individuals without these conditions.9,10,11,12,13,14,15

To date, however, little attempt has been made to investigate the mechanisms through which dental conditions impact on children's OHRQoL. There is some evidence to suggest that the association between clinical variables and child outcomes is complex and that a number of variables may moderate this relationship. For example, a study by Marshman and colleagues16 found that enamel defects impacted most on those children whose sense of self was defined by their appearance. This indicates that a child's subjective assessment of their own dental appearance may play an important role in how visible dental differences impact on their OHRQoL.

Gender may moderate the relationship between visible orofacial conditions and OHRQoL outcomes. While it would appear that children are actually very aware of their dental aesthetics, irrespective of gender or social background,17 previous research has found that females with facial differences are more likely to report negative effects and tend to be more dissatisfied with the appearance of their dentition than their male counterparts.18,19,20

Significant life events may also influence the impact of visible dental differences on children's OHRQoL. The educational transition from primary to secondary school can be a challenging and stressful life event for many children.21,22 It has been suggested that there is an increased emphasis on social interactions as children move into secondary schools and that 'fitting in' and 'belonging' become of key importance.23 Children's educational attainment and self-esteem have both been found to suffer during their transition to a new school.24 It is therefore conceivable that children who have visible dental conditions may report increased impacts on their OHRQoL during this transitional stage. However, it has been proposed that the transition to secondary school could also be viewed as a life event which may have positive, as well as negative, effects.21

Therefore, the aim of this project was to investigate the impact of gender, visible dental differences and self-reported satisfaction with dental appearance on children's OHRQoL during their educational transition from primary to secondary school. The findings presented in this paper represent part of a larger research project that explored the experiences of children with and without dental differences during their transition to secondary schools, using both qualitative and quantitative approaches.25

Materials and methods

Participants

A power calculation was initially conducted based on an effect size of f2 = 0.20, statistical power aimed at 1-β = 0.95, and a significance level of 0.05, and revealed that there would need to be at least 72 participants in the longitudinal study in order to be able to detect main and interaction effects using the repeated measures ANOVAs (for example, maximum of three predictors and six groups inclusive of 'time 1' and 'time 2').

The study group was drawn from regular attenders and new patient referrals at the Charles Clifford Dental Hospital, Sheffield. The case notes of all children aged 10-11 years (school year 6) at the time of study commencement (January 2008) were identified using a computerised hospital patient database. Children with a learning disability, significant medical history or orthodontic appliance were excluded from the study, leaving 216 potential participants (42.6% boys and 57.4% girls).

These children's dental records were reviewed by one of the authors (HDR) to determine the current clinical condition of each child's upper permanent incisor teeth. The appearance of the incisors was recorded as 'normal' or 'abnormal' on the basis of having any one of five conditions (trauma, enamel defects, gross caries, hypodontia, abnormal morphology). The orthodontic status was also categorised as 'normal' (no malocclusion) or 'abnormal' (class II or III incisor relationships, rotations, displacements, crowding or spacing).3,26 For the purposes of statistical analysis, participants were divided into two dental groups for comparison: i) normal or ii) abnormal incisor aesthetics and/or occlusion.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the South Sheffield Research Ethics Committee and study conduct was monitored throughout by local research governance processes.

Measures used

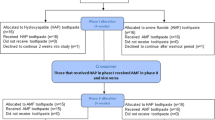

Three months before secondary school entry, children and their parents/care-givers were sent a study package which comprised child and parent study information sheets, parental consent and child assent forms, a questionnaire booklet and a prepaid envelope. The child's oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) was measured using a short form of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ11-14).27 The Impact Short Form (ISF-16) CPQ11-14 was developed through item impact methodology and is composed of 16 items comprising four oral health domains (oral symptoms, functional limitations, emotional well-being and social well-being). The participant is asked 'In the past few weeks how often have you [had/been item] because of your teeth or mouth?' Example items include 'pain in your teeth or mouth' and 'felt shy'. The response options are 'Never' = 0; 'Once/twice' = 1; 'Sometimes' = 2; 'Often' = 3; 'Everyday/almost everyday' = 4. Higher scores indicate more frequent impacts and thus worse OHRQoL. Participants were also asked to rate their satisfaction with the appearance of their teeth in response to the question: 'How satisfied are you with the appearance of your teeth?' A five-point response format, ranging from 'Very satisfied' = 0 to 'Very dissatisfied' = 4, was provided. For the purpose of statistical analysis, participants were divided into two groups: i) 'satisfied' (very satisfied or satisfied) or ii) 'not satisfied' (neither satisfied/dissatisfied, dissatisfied or very dissatisfied).

Follow-up data on OHQoL and self-reported satisfaction with dental appearance were obtained by mailing the same questionnaire to the children three months after they had started secondary school (December 2008).

For both the initial and follow-up questionnaires, if no response had been received after one month, another copy of the questionnaire was mailed. In order to maximise response rates the design of the evaluation questionnaire was informed by a recent Cochrane systematic review on increasing response rates to postal questionnaires, which included the use of personalised letters, the use of coloured ink and the inclusion of pre-paid envelopes in the study pack.28

Following receipt of the follow-up questionnaires, the dental records of each respondent were reviewed again. A note was made of any patients where there had been a change to incisor appearance, such as the provision of an orthodontic appliance or anterior restoration.

Data analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to detail the extent and nature of any differences in OHRQoL based on visible dental differences, satisfaction with dental appearance, gender, and transition to secondary school. Interaction effects between these variables were examined to investigate possible moderating pathways. Data for the CPQ total score and subscales were positively skewed and were therefore transformed using square root transformations before conducting analysis of variance tests.

Results

Baseline participants

Ninety-two children completed the baseline questionnaire, giving a response rate of 43%: 60 (65.2%) girls and 32 (34.8%) boys. Fifty-two (56.5%) children were classified as having a visible dental difference. Fifty (54.3%) participants were 'satisfied' with their dental appearance.

Oral health-related quality of life at baseline

Means and standard deviations for the total CPQ and the four sub-scales are presented in Table 1. Bivariate analysis revealed that children who had been categorised as having visible differences were more likely to be dissatisfied with their dental appearance than those who had not (r = 0.28, p <0.01).

In order to examine any impact on OHRQoL of gender, having a visible dental difference, and satisfaction with dental appearance, a three-way ANOVA was conducted on the CPQ total, with clinical dental group (visible/no visible difference), appearance group (satisfied/not satisfied) and gender (boys/girls) as the independent variables. There was a main effect of dental group (F(1, 91) = 6.61, p <0.05), with the no visible difference group having a lower CPQ score than the visible difference group (Table 1). There was also a main effect of appearance (F(1, 91) = 6.82, p <0.05), with those who were satisfied with their dental appearance having a lower CPQ score. There was no main effect of gender and no significant interaction effects between gender, dental group and appearance group.

In order to determine which domains of OHRQoL were affected by the variables under investigation a 2 (gender) × 2 (dental group) × 2 (appearance group) × 4 (symptoms, functional limitation, emotional well-being, social well-being) MANOVA was conducted on the CPQ subscales. There was an overall main effect of dental group on OHRQoL subscales (F(4, 81) = 3.56, p <0.01). The univariate tests revealed that this effect was significant for functional limitation (F(1, 91) = 7.77, p <0.01), emotional well-being (F(1, 91) = 5.28, p <0.05) and social well-being (F(1, 91) = 10.76, p <0.01), but not for symptoms (Table 1). The results also revealed a significant overall effect of appearance group on OHRQoL subscales (F(4, 81) = 4.38, p <0.01). Univariate tests revealed that the effect was significant for emotional (F(1, 91) = 14.65, p <0.001) and social well-being (F(1, 91) = 4.12, p <0.05) but not for symptoms or functional limitation. There was no main effect of gender or any gender, dental group and appearance group interactions for the OHRQoL subscales.

Follow-up participants

Of the 92 baseline participants, 71 children completed questionnaires at follow-up (77% response rate). The female to male ratio was similar to that at baseline with 48 (67.6%) girls and 23 (32.4%) boys. Forty-four (62.0%) of the participants had a visible dental difference. Only nine children (12.7%) had experienced dental treatment which could have resulted in a positive or negative change to their dental appearance; for example, being fitted with a denture or fixed orthodontic appliance.

Oral health-related quality of life following educational transition

Thirty-nine (54.9%) of the participants were satisfied with their appearance at follow-up. In all cases, OHRQoL improved at follow-up (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Given the small sample size, two separate sets of analyses were conducted: (i) time, dental group and gender, and (ii) time and appearance group. In all analyses, change in dental status was entered as a covariate.

In order to assess whether educational transition (time), dental group, and gender impacted upon OHRQoL at follow-up, a series of 2 (time) × 2 (dental group) × 2 (gender) repeated measure ANOVAs were conducted on the data. For the total CPQ score, there were main effects of time (F(1, 65) = 18.05, p <0.001) and dental group (F(1, 65) = 6.37, p <0.01), and a three-way time × gender × clinical group interaction (F(1, 65) = 4.64, p <0.05). Although all groups showed a decrease in CPQ scores following transition (ie they had better OHRQoL), girls with a visible dental difference had higher CPQ scores at follow-up than the other three groups and their OHRQoL improved less over time than their male counterparts (Fig. 1).

For the CPQ sub-scales, there was a main effect of educational transition (time) for symptoms (F(1, 65) = 17.82, p <0.001), emotional well-being (F(1, 65) = 8.02, p <0.01) and social well-being (F(1, 65) = 6.82, p <0.01). There was a main effect of dental group for functional limitations (F(1, 65) = 6.85, p <0.01), emotional well-being (F(1, 65) = 5.89, p <0.05) and social well-being (F(1, 65) = 5.60, p <0.05); the visible dental difference group had worse OHRQoL sub-scale scores than the no visible dental difference group. There was also a three-way time × dental group × gender interaction (F(1, 65) = 5.21, p <0.05). At baseline, the visible difference group had higher sub-scale scores than the no visible difference group. Following transition, boys with a visible difference showed increased improvements in OHRQoL compared to the girls with visible differences, whose CPQ sub-scale scores remained higher than the other groups.

In order to assess the impact of educational transition (time) and satisfaction with appearance upon OHRQoL at follow-up, a series of 2 (time) × 2 (satisfaction) repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted on the data. There was a main effect of appearance group for CPQ total score (F(1, 68) = 13.61, p <0.001) and each of the sub-scales: symptoms (F(1, 68) = 5.42, p <0.05), functional limitations (F(1, 68) = 7.83, p <0.01), emotional well-being (F(1, 68) = 17.66, p <0.001), and social well-being (F(1, 68) = 9.57, p <0.01). In all cases, those who were not satisfied with their appearance at baseline had worse OHRQoL scores at follow-up than those who were satisfied with their dental appearance at baseline.

Discussion

Findings in relation to oral health-related quality of life

The results from the present study revealed that children with a visible dental difference reported significantly more impacts on their OHRQoL than children without a visible dental difference (baseline mean = 17.4 vs 9.9; follow-up mean = 7.1 vs 1.8). The baseline CPQ score for those children with a visible dental difference was similar to the scores which have previously been reported for children with orofacial conditions (mean = 16.5, SD = 8.3) and higher than the scores reported for children with caries (11.9, SD = 9.4) and malocclusions (mean = 13.0, SD = 7.6).27 These findings are also consistent with previous research which has identified a number of different visible dental differences (eg malocclusion, dental trauma, severe fluorosis and hypodontia) that are associated with worse OHRQoL in children.9,11,12,14,15,29,30 Of the OHRQoL domains, it was the impact on emotional and social well-being that was most noticeable. Again, this is consistent with earlier findings which suggest poor dental aesthetics may have a number of psychosocial impacts on children's OHRQoL.11

Children with a visible dental condition also reported increased dissatisfaction with their dental appearance. While dissatisfaction with dental appearance was associated with worse OHRQoL, the baseline data revealed that children who were dissatisfied with their dental appearance did not report a higher number of functional limitations or oral symptoms than children who were satisfied with their appearance. This suggests that impacts associated with the dissatisfaction of dental appearance are primarily emotional and social in nature. Interestingly, children's satisfaction with their dental appearance did not moderate the relationship between dental group and OHRQoL. This is perhaps surprising in light of previous findings that indicate the impact of dental conditions is influenced by children's subjective assessment of the importance of appearance.16 However, it is possible that a mediating relationship exists between dental group, satisfaction with appearance and OHRQoL, which was not investigated in this current study.

The substantial decrease in CPQ scores at follow-up was unexpected considering the negative impacts that transition to secondary school can have on children's self-esteem.24,31 This finding is perhaps even more surprising considering that satisfaction with dental appearance was unchanged with time, and therefore could not explain the improvement in OHRQoL. Interestingly, at follow-up children with visible dental differences also reported relatively low levels of impacts on their OHRQoL, despite still having a variety of dental anomalies and orthodontic malocclusions.

There are, however, a number of possible explanations for the positive change in children's OHRQoL scores following educational transition. Firstly, the use of CPQ baseline and follow-up scores as a reliable indicator of change is open to certain methodological considerations. The ability for a measure to reliably detect a difference in OHRQoL when one is actually present (its responsiveness to change), is a controversial issue.32,33 While the ISF CPQ11-14 measure has demonstrated substantial test-retest reliability over short re-test periods (eg two-week intervals27) it is possible that the CPQ could be vulnerable to measurement error over longer periods of time. It is also possible that OHRQoL may not be a stable construct. Indeed, previous research which investigated the OHRQoL of adults, using a global oral health rating, found that just under half of adults did not report steady patterns of change in their OHRQoL in line with clinical variables, but rather reported fluctuations in their OHRQoL over four points in time.34 Future research could subject measures of OHRQoL to path analysis techniques, aimed at distinguishing true reliability from temporal instability.35 It should also be recognised that the examination of before and after scores alone does not provide information about the number of children who experienced an improvement in their OHRQoL or answer questions related to the magnitude or meaningfulness of these changes.31,36

If it is, however, to be accepted that the measure has reliably assessed a true change in children's OHRQoL, then the examination of the CPQ subscales allows exploration of other possible explanations for this apparent improvement in OHRQoL. The finding that children's emotional well-being improved following educational transition may suggest that children were most anxious about their oral health before starting a new school, and that these fears were allayed once the move had been made. The observed decrease in social impacts over time could also suggest that children experienced less questioning or stigmatisation about their dental appearance in their new school environment. There is certainly some evidence to suggest that adolescents are less likely than younger children to make negative social judgements about children who have visible dental differences.37

It is also possible that key psychosocial factors, which were not assessed in this study, explained some of the variation in OHRQoL over time. Indeed, previous research has revealed that an individual's coping strategies and self-esteem may be important determinants of OHRQoL.38,39 Therefore, this study formed part of a larger research project which also investigated the relationship between these variables and children's OHRQoL during educational transition, which will be reported in future communications.

While gender was not a direct predictor of children's OHRQoL during transition to secondary school, girls with dental differences reported least improvement in their OHRQoL at follow-up. This is consistent with previous research which has found that females with a range of different dental conditions experience worse OHRQoL than their male counterparts.11,40

Study design

While the study offers insights into the potential impact of dental status on children's OHRQoL during transition to secondary school, the study was not without limitations.

It should be recognised that just under half of the children invited to participate in this study completed and returned questionnaires. Therefore, the experiences of this group of children may not be representative of the experiences of children who, for whatever reason, decided not to participate in the study. Further enquiry would be warranted to compare the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of young patients who agree or decline to take part in oral health research, to determine whether any fundamental differences do exist between these two groups.

The CPQ measure used to assess OHRQoL has been criticised for solely focusing on the frequency of impacts on children's oral health and well-being. It has been proposed that the actual severity of these impacts and how much they affect children should also be assessed.16,41 No attempt was made to explore OHRQoL in relation to the exact nature of the dental conditions (eg genetic enamel defect, non-vital discoloured incisor, increased overjet, etc) as the subgroups were too small for meaningful statistical analysis.

One of the study's main strengths, however, was the use of follow-up questionnaires. To date, there have been few longitudinal studies using paediatric oral health-related quality of life measures. Thus, the study has provided further evidence for the dynamic nature of oral health-related quality of life with respect to life events.

Clinical relevance

The initial prompt for this study arose directly from clinical observations: there was a perception of heightened dental appearance-related anxiety among some children just before their transition to secondary school. Thus, there was anecdotal evidence of increased psychosocial impact for some children with dental differences with the anticipation of meeting new peers in a new environment. One of the most interesting findings, therefore, was that the impact of various dental conditions actually appeared worse just before the school move, and did not generally persist once the transition had been made. Nonetheless, it is important that clinicians provide opportunities for children to voice any concerns about their own oral health and appearance, and are inclusive of children in treatment decisions.

References

Bailleul-Forestier I, Molla M, Verloes A, Berdal A . The genetic basis of inherited anomalies of the teeth: part 1: clinical and molecular aspects of non-syndromic dental disorders. Eur J Med Genet 2008; 51: 273–291.

Crawford P J, Aldred M J . Anomalies of tooth formation and eruption. In Paediatric dentistry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Chadwick B, Pendry L . Children's dental health in the United Kingdom 2003: non-carious dental conditions. London: Office for National Statistics, 2004.

Chestnutt I, Pendry L, Harker R . Children's dental health in the United Kingdom 2003: the orthodontic condition of children. London: Office for National Statistics, 2004.

Harris D . Types, causes and treatment of physical difference. In Lansdown, Rumsey N, Bradbury E, Carr T, Partridge J (eds) Visibly different: coping with disfigurement. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1997.

Rodd H D, Barker C, Baker S R, Marshman Z, Robinson P G . Social judgements made by children in relation to visible incisor trauma. Dent Traumatol 2010; 26: 2–8.

Rodd H D, Abdul-Karim A, Yesudian G, O'Mahony J, Marshman Z . Seeking children's perspectives in the management of visible enamel defects. Int J Paediatr Dent 2011; 21: 89–95.

Rodd H D, Atkin J M . Denture satisfaction and clinical performance in a paediatric population. Int J Paediatr Dent 2000; 10: 27–37.

Coffield K D, Phillips C, Brady M et al. The psychosocial impact of developmental dental defects in people with hereditary amelogensis imperfecta. J Am Dent Assoc 2005; 136: 620–630.

Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M et al. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res 2002; 81: 459–463.

O'Brien K, Wright J L, Conboy F, Macfarlane T, Mandall N . The child perception questionnaire is valid for malocclusions in the United Kingdom. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006; 129: 536–540.

Ramos-Jorge M L, Bosco V L, Peres M A, Nunes A C G P . The impact of treatment of dental trauma on the quality of life of adolescents – a case-control study in Southern Brazil. Dent Traumatol 2007; 23: 114–119.

Cortes M I S, Marcenes W, Sheiham A . Impact of traumatic injuries to the permanent teeth on the oral health-related quality of life in 12–14 year old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002; 30: 193–198.

Berger T D, Kenny D J, Casas M J, Barrett E J, Lawrence H P . Effects of severe dentoalveolar trauma on the quality-of-life of children and parents. Dent Traumatol 2009; 25: 462–469.

Fakhruddin K S, Lawrence H P, Kenny D J, Locker D . Impact of treated and untreated dental injuries on the quality of life of Ontario school children. Dent Traumatol 2008; 24: 309–313.

Marshman Z, Gibson B, Robinson P G . The impact of developmental defects of enamel on young people in the UK. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2009; 37: 45–57.

Burden D J, Pine C M . Self-perception of malocclusion among adolescents. Community Dent Health 1995; 12: 89–92.

Shaw W C . Factors influencing the desire for orthodontic treatment. Eur J Orthod 1981; 3: 151–162.

Strauss R P, Ramsey B L, Edwards T C et al. Stigma experiences in youth with facial differences: a multi-site study of adolescents and their mothers. Orthod Craniofac Res 2007; 10: 96–103.

Peres K G, Barros A J D, Anselmi L, Peres M A, Barros F C . Does malocclusion influence the adolescent's satisfaction with appearance? A cross-sectional study nested in a Brazilian birth cohort. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2008; 36: 137–143.

Sirsch U . The impending transition from primary to secondary school: challenge or threat? Int J Behav Dev 2003; 27: 385–395.

Jindal-Snape D, Miller D J . A challenge of living? Understanding the psycho-social processes of the child during primary-secondary transition through resilience and self-esteem theories. Educ Psychol Rev 2008; 20: 217–236.

Isakson K, Jarvis P . The adjustment of adolescents during the transition into high school: a short-term longitudinal study. J Youth Adolesc 1999; 28: 1–24.

Blyth D A, Simmons R G, Carlton-Ford S. The adjustment of early adolescents to school transitions. J Early Adolesc 1983; 3: 105–120.

Marshman Z, Baker S R, Bradbury J, Hall M J . The psychosocial impact of oral conditions during transition to secondary education. Eur J Paediatr Dent 2009; 10: 176–180.

Brook P H, Shaw W C . The development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Orthod 1989; 11: 309–320.

Jokovic A, Locker D, Guyatt G . Short forms of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire for 11-14-year old children (CPQ11–14): development and initial evaluation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006; 4: 4.

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M et al. Methods to increase response rates to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (2), MR000008.

Chankanka O, Levy S M, Warren J J, Chalmers J M . A literature review of aesthetic perceptions of dental fluorosis and relationships with psychosocial aspects/oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2010; 38: 97–109.

Locker D, Jokovic A, Prakash P, Tompson B . Oral health-related quality of life of children with oligodontia. Int J Paediatr Dent 2010; 20: 8–14.

Simmons R G, Blyth D A, Van-Cleave E F, Bush D . Entry into early adolescence: the impact of school structure, puberty and early dating on self-esteem. Am Sociol Rev 1979; 44: 948–967.

Allen P F . Assessment of oral health related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1: 40.

Worthington H V . Statistical aspects of measuring change in oral health status of older adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1998; 26: 48–51.

Dolan T A, Peek C W, Stuck A E, Beck J C . Three-year changes in global oral health rating by elderly dentate adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1998; 26: 62–69.

Heise D R . Separating reliability and stability in test-retest correlation. Am Sociol Rev 1969; 34: 93–101.

Locker D . Issues in measuring change in self-perceived oral health status. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1998; 26: 41–47.

Rodd H D, Murray A M, Yesudian G, Lewis B R . Decision-making for children with traumatized permanent incisors: a holistic approach. Dent Update 2008; 35: 439–440.

Heydecke G, Tedesco L A, Kowalski C, Inglehart M R . Complete dentures and oral health-related quality of life – do coping styles matter? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004; 32: 297–306.

Agou S, Locker D, Streiner D L, Tompson B . Impact of self-esteem on the oral-health-related quality of life of children with malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008; 134: 484–489.

Mat A . The determinants and consequences of children's oral health related quality of life. Sheffield: University of Sheffield, 2009. PhD Thesis.

Locker D, Allen F . What do measures of 'oral health-related quality of life' measure? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2007; 35: 401–411.

Acknowledgements

A big thank you goes to all the children who gave up their time to participate in the study. Our gratitude goes out to the staff in the Paediatric Dental Clinic at the Charles Clifford Dental Hospital, whose help in the data collection stage of this project was greatly appreciated. Thanks are also given to Sheffield Children's Hospital Charitable Trust for funding this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodd, H., Marshman, Z., Porritt, J. et al. Oral health-related quality of life of children in relation to dental appearance and educational transition. Br Dent J 211, E4 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.574

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.574