Key Points

-

Bullying is endemic in schoolchildren.

-

The effects of bullying in schoolchildren can result in both psychological and physical symptoms.

-

Children with an untreated malocclusion appear to be at greater risk of bullying.

-

Management of bullying due to the presence of a malocclusion should involve school anti-bullying policies and referral to medical and dental specialties.

Abstract

Bullying in school-aged children is a global phenomenon. The effects of bullying can be both short- and long-term, resulting in both physiological and psychological symptoms. It is likely that dental care professionals will encounter children who are subjected to bullying. The aim of this narrative review is to discuss the incidence of bullying, the types of bullying, the effects of bullying and the interventions aimed at combating bullying in schoolchildren. The role of dentofacial aesthetics and the relationship of bullying and the presence of a malocclusion are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bullying or peer victimisation among schoolchildren is endemic.1 Recent media coverage including national campaigns and social networking sites within the United Kingdom have focused on the issue and brought it into the public domain. Its extent is further highlighted by the finding that between 1997 and 1998, 17% of all calls received by Childline were related to bullying.2

Bullying has been defined as 'a specific form of aggressive behaviour'3 and can be described as a situation when a student 'is exposed repeatedly and over time, to negative actions on the part of one or more students'.3 Negative actions can be classified as direct or indirect forms of aggression that cause harm to the victim.4 The definition of bullying has been reported to vary according to the age of the child,5 between teachers and adolescents6,7 and due to variations in cultural terminology used in the translation of bullying. Smith and co-workers5 reported that eight-year-olds fail to recognise differences between direct and indirect forms of aggressive behaviour compared to an older peer group. However, with increasing age this difference seems to reduce as the child develops more sophisticated definitions of bullying including recognition of indirect forms.7 Both teachers and adolescent pupils tend to restrict their definition of bullying to direct forms only.6,7

Teasing and bullying – are they the same?

Both teasing and bullying are regarded as aggressive behaviours but lie on opposite ends of the spectrum. Teasing is regarded as a mild form of aggressive behaviour often jovial in nature, carried out between peers with no significant harm intended to the recipient. In contrast, bullying in whatever form it occurs results in distress and harm to the individual. It should be remembered that if teasing results in harm and distress then it should be considered as bullying.8

Prevalence of bullying in school-aged children

The reported prevalence of bullying in school-aged children shows great variation (Table 1). Factors responsible for this variation include: study design, age of participants, cultural differences, variation in the translation of bullying, the time frame used to determine the frequency of bullying and the different criteria used to differentiate between victims and non-victims of bullying.9

In the UK, three large sample cross-sectional studies have investigated peer victimisation in school-aged children. Boulton and Underwood10 reported that 26% of eight- and nine-year-olds are bullied 'sometimes or more often' and 10% are bullied 'several times a week'. Within the 11- to 12-year-old age group, 15% are bullied 'sometimes or more often' and 2% 'several times a week'. Whitney and Smith11 reported that 27% of eight- to 11-year-olds are 'bullied sometimes' and 10% 'bullied at least once a week'. In children aged between 11 and 16 years, 10% are 'bullied sometimes' and 4% 'bullied at least once a week'.

Salmon and co-workers12 reported 4.2% of adolescents aged between 12 and 17 years as being bullied 'sometimes or more often'. It is evident that the incidence of bullying reduces with increasing age. Olweus3 suggested that with increasing psychological and physiological development children become less vulnerable and less tolerant of aggressive behaviour. However, bullying should not be viewed as 'an accepted part of a child's normal development' and 'transient' in nature.10

Gender differences and type and location of bullying

Both male and female children can be exposed to direct and indirect forms of bullying. The literature suggests there are gender differences in the frequency of bullying. It has been reported that males tend to be bullied more than females19,20 but this is not universal.9,10,22 Subtle variations exist: males are more likely to endure direct forms of aggression such as physical attacks, but in contrast females are exposed to more indirect types such as spreading rumours, gossiping and isolation.3,10,15 The prevalence of indirect aggression is possibly underestimated due to the failure of both individuals and teachers to recognise it as a form of bullying.6,7

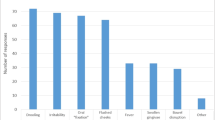

The most common form of direct aggression is verbal abuse comprising of name-calling.9,10 Fekkes and co-workers22 reported the frequency of name calling at 30.9%, followed by spreading rumours at 24.8% and physical forms such as kicking and pushing at 14.7%. Within the school environment the playground is the most common location for bullying to occur. Glew and co-workers16 reported the locations and frequency of bullying as: playground (71%), classroom (46%), gym classes (40%), lunchroom (39%), in halls and stairways (33%) and on the buses (28%).

Both at school and at home children can freely communicate with each other via various multimedia applications and devices. Recently, the concept of 'cyberbullying' has been documented. Smith and co-workers23 reported the prevalence of cyberbullying at 14.1% within the UK; it usually takes the form of written messages or images, sent via mobile phones or instant messages.

Can victims and bullies be identified?

Currently there are no accepted psychological profiles or accurate assessments to identify bullies and victims.24 However, certain personality traits have been associated with both categories. Victims have been found to be anxious, insecure, cautious, sensitive and quiet, to appear weak and withdrawn and to have low self-esteem. Within social interactions victims often take on a submissive role and show a lack of assertiveness.25 Although these traits may have resulted from persistent victimisation, they could have acted as the stimulus for the initial onset of bullying.25 This reinforces the concept of a 'victim' personality, which remains with the individual despite changes in the social situation.26 In contrast, bullies tend to be aggressive towards peers and adults and physically strong with good or inflated self-esteem, the need to dominate others and a positive attitude towards violence. Long-term bullies tend to develop both social and behavioural problems including psychiatric symptoms and involvement in crime and alcohol abuse.3,27

What are the effects of bullying?

Peer victimisation among school children can result in both physical and psychological symptoms (Table 2). Academic performance may also suffer as a result.16 Reported detrimental effects also include an increased rate of suicidal ideations, suicidal risk and self-injurious behaviour within students subjected to peer victimisation.29

The long-term effects of bullying have also been investigated. The victims of bullying are more likely to remain anxious and depressed.30 In particular, bullied females are at a higher risk of developing mental health problems. This finding was supported by Rigby,31 who postulated that this was related to the increased frequency of indirect bullying experienced by females compared to males. The psychological effects of peer victimisation in school-aged children can continue during the transition to senior school31 and into adulthood. Longitudinal investigation of children who were seriously bullied at age 11 revealed the persistence of low self-esteem and depression as young adults.3

Interventions for the bullied child

Peer victimisation within a school environment is a complex process of social interaction between parents, peer groups and teachers.32 The primary objective is to modify behaviour and the environment between these three groups of individuals. Since 1999 it has become a legal requirement for all schools within the UK to have an anti-bullying policy in place.33

In the early 1990s the Olweus anti-bullying programme was developed in Bergen, Norway.3 It is based on the assumption that peer victimisation is a specific behaviour aimed at gaining particular social outcomes such as dominance or status among peers. This behaviour is reinforced by inactive bystanders, that is, peer groups and the lack of deterrent from adults and peers. The programme's aims include: creation of a social environment with clear rules against bullying behaviour, increasing awareness of bullying, adult supervision during scheduled breaks, providing support and protection for individuals who are bullied and encouraging active participation by teachers, peers and parents to resolve bully/victim incidents. In the UK, the Department for Schools and Education's anti-bullying pack 'Don't suffer in silence: an anti-bullying pack for schools'34 was created following the findings reported by Smith and Sharp35 and adapted from the Olweus anti-bullying programme.

School-based anti-bullying programmes have been shown to be effective. Olweus3 reported a 50% reduction in students being bullied 'now and then' or more frequently. In addition, there was a decrease in the number of reported new victim cases. Smith and Sharp35 and Fekkes and co-workers36 reported 15-20% and 25% reductions in bullying incidents respectively as a result of anti-bullying programmes. Longitudinal assessments of anti-bullying programmes demonstrate a positive effect overall and improvement in student academic achievements.37

Anti-bullying measures can also incorporate peer support systems38 and peer group modification techniques,39 which aim to improve interpersonal relationships between students. These systems consist of students mentoring and befriending individuals, conflict resolution and counselling. Adults and teachers maintain a supportive and supervisory role. Naylor and Cowie38 reported that although peer support systems do not reduce bullying behaviour, they are effective at combating the negative effects of peer victimisation.

Peer group modification aims to focus on students who are not directly involved in bully/victim incidents, that is, bystanders, by alteration of their attitudes and behaviours.39 It has been suggested that peer group influence plays an important role in developing and maintaining bullying behaviour.24 Active intervention of bystanders to prevent bullying incidents is an effective method in eliminating and denying bullies their audience and dominance.

The role of the clinician

It is reasonable to assume that clinicians will encounter children who are experiencing bullying at school; the question remains as to what course of action should be taken. Lyznicki and co-workers24 suggested the clinician's role involves:

-

1

Identifying children at risk

-

2

Counselling families

-

3

Screening for psychiatric co-morbidities

-

4

Advocation for prevention.

Identification of at-risk children can be difficult. Certain personality traits are common in either victims or bullies; however, care should be taken to avoid stereotyping children into groups. Unexplained physical and psychological symptoms and behavioural changes may be the initial presentation of peer victimisation. If a child admits that he/she is being bullied, it is critical that the child be believed and reassured that they have done the right thing to report it.24,40 Parents of bullied children should be counselled and informed of the severity and possible consequences of bullying. They should be encouraged to contact the school and speak to teachers, the headteacher or governors regarding the situation and request action is taken. Further information regarding bullying aimed at schoolchildren and their parents can be freely obtained from specialised organisations (Table 3) and the Department for Education website.41 If psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety are evident then a referral for a psychological assessment should be requested after liaising with the patient's general medical practitioner. For dental care practitioners clear guidance is lacking; however, any intervention should be focused primarily on the school environment and instigation of anti-bullying policies but may involve other specialties (Table 4).

Dentofacial aesthetics and bullying

Facial appearance has a unique role in society.42 Deviation of normal dentofacial aesthetics can affect an individual's psychosocial status and result in social disadvantage.43 It is generally assumed that an individual with poor dentofacial aesthetics will have low self-esteem42 and elicit an unfavourable response from society. However, this response is unpredictable. Macgregor suggested that severe facial disfigurement evokes feelings of sympathy and compassion but milder disfigurements result in ridicule and teasing, creating greater psychological distress in these individuals.44 More importantly, background facial attractiveness appears to be more influential than the individual's dental appearance.45 Shaw and co-workers46 also commented that features such as height and weight can be targeted during teasing. The face is an important communication tool, often portraying an individual's emotions and level of self-image.44 Modern society is driven by the need to conform to ideals; perceived dentofacial aesthetics can influence both opinions formed of an individual by peers and adults and the perception of an individual's personality.45,47 Interestingly, negative biases regarding profile can be inferred at age 10-11 years.48 Individuals with normal incisor alignment are regarded as more desirable as friends, attractive, intelligent, of higher social class and less aggressive in comparison with individuals with a malocclusion.45,47,49 Individuals with high levels of facial attractiveness also elicit a more favourable response from society compared to those with low levels.42,47 In addition, the importance of having good dentofacial appearance is recognised as important in making friends, career progression and dating.50

The relationship between malocclusion and psychosocial well-being is complex. Particular dental characteristics have been identified that increase the risk of teasing, resulting in disruption of normal psychological development. These include maxillary crowding, an increased overjet and deep overbite.46,51,52 Additional dental features include dentoalveolar trauma,53 absent teeth54 and cleft lip with or without cleft palate.55 Peer victimisation and bullying is deemed a negative response from society. The question remains, is there a relationship between malocclusion and being bullied during adolescence and what are its effects? This question was recently investigated by Seehra and co-workers.56 In this cross-sectional study a cohort of children aged between 10 and 14 years with an untreated malocclusion were given questionnaires which measured the self-reported frequency and severity of bullying, the individual's self-esteem and oral health-related quality of life. Orthodontic treatment need and malocclusion severity were assessed using IOTN. In this study the reported prevalence of bullying in adolescents with a malocclusion was reported at 12.8% and was significantly associated with a Class II Div 1 incisor relationship, increased overbite, increased overjet and a high need for orthodontic treatment. Being bullied due to the presence of a malocclusion resulted in a significant negative impact on both self-esteem and oral health-related quality of life. It is apparent that these individuals are deserving of intervention, but is orthodontic treatment the answer? Historically, orthodontic appliances are reported to attract comments such as 'metal mouth' and 'scaffolding', resulting in potential worsening of the teasing.57 However, further research is still required to determine the impact of interceptive orthodontic treatment and subsequent psychosocial benefit in bullied adolescents with a malocclusion. It may be prudent in such cases to warn patients that treatment may be beneficial but may not totally eliminate the situation, as other factors could be involved.

It is clear that a complex relationship exists between the presence of a malocclusion, bullying, self-esteem and oral health-related quality of life. The self-perception of dentofacial aesthetics has been reported to have a greater effect on self-esteem and self-concept.58 However, evidence suggests that a malocclusion can have a negative impact on both an individual's self-esteem59 and oral health-related quality of life.60 In bullied individuals it may be the case that a clear cause-and-effect relationship is not present and that a combination of factors act synergistically to cause a negative impact on an individual's psychosocial wellbeing.56

Currently the severity and need of orthodontic treatment within the UK is judged on occlusal and aesthetic impairment without consideration of psychosocial factors. It may be the case that the latter should be incorporated into current and future indices or at least considered, despite limitations of validation and reproducibility.

Summary

Tolerance of bullying in school-aged children should not be accepted in whatever form it occurs. Dawkins40 suggested that 'to ignore bullying is to condemn children to further misery and may prejudice their academic achievements and adjustment in adult life'. Clinicians should be aware that children with a malocclusion could be subjected to persistent peer victimisation, resulting in a negative impact on both their self-esteem and oral health-related quality of life. In this situation referral for orthodontic assessment and treatment should be considered.

References

DiBiase A T, Sandler P J . Malocclusion, orthodontics and bullying. Dent Update 2001; 28: 464–466.

ChildLine. ChildLine annual review 1997/8. London: ChildLine, 1998.

Olweus D. Bullying at school: basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1994; 35: 1171–1190.

van der Wal M F, de Wit C A, Hirasing R A . Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 1312–1317.

Smith P K, Cowie H, Olafsson R F et al. Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen-country international comparison. Child Dev 2002; 73: 1119–1133.

Boulton M J. Teachers' views on bullying: definitions, attitudes and ability to cope. Br J Educ Psychol 1997; 67: 223–233.

Naylor P, Cowie H, Cossin F, de Bettencourt R, Lemme F . Teachers' and pupils' definitions of bullying. Br J Educ Psychol 2006; 76: 553–576.

Pearce J. What can be done about bullying? In Elliot M (ed) Bullying: a practical guide to coping for schools. 3rd ed. pp 74–75. London: Pearson Education, 2002.

Solberg M, Olweus D . Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior 2003; 29: 239–268.

Boulton M J, Underwood K . Bully/victim problems among middle school children. Br J Educ Psychol 1992; 62: 73–87.

Whitney I, Smith P K . A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/middle and secondary schools. Educ Res 1993; 35: 325.

Salmon G, James A, Smith D M . Bullying in schools: self reported anxiety, depression, and self esteem in secondary school children. BMJ 1998; 317: 924–925.

Forero R, McLellan L, Rissel C, Bauman A . Bullying behaviour and psychosocial health among school students in New South Wales, Australia: cross sectional survey. BMJ 1999; 319: 344–348.

Fekkes M, Pijpers F I, Verloove-Vanhorick S P. Bullying behavior and associations with psychosomatic complaints and depression in victims. J Pediatr 2004; 144: 17–22.

Baldry A C, Farrington D P . Brief report: types of bullying among Italian school children. J Adolesc 1999; 22: 423–426.

Glew G M, Fan M Y, Katon W, Rivara F P, Kernic M A . Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005; 159: 1026–1031.

Kshirsagar V Y, Agarwal R, Bavdekar S B . Bullying in schools: prevalence and short-term impact. Indian Pediatr 2007; 44: 25–28.

Alikasifoglu M, Erginoz E, Ercan O, Uysal O, Albayrak-Kaymak D. Bullying behaviours and psychosocial health: results from a cross-sectional survey among high school students in Istanbul, Turkey. Eur J Pediatr 2007; 166: 1253–1260.

Nansel T R, Overpeck M, Pilla R S, Ruan W J, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P . Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 2001; 285: 2094–2100.

Kim Y S, Koh Y J, Leventhal B L . Prevalence of school bullying in Korean middle school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004; 158: 737–741.

Perry D G, Kusel S J, Perry L C . Victims of peer aggression. Dev Psychol 1998; 24: 807–814.

Fekkes M, Pijpers F I, Verloove-Vanhorick S P. Bullying: who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Educ Res 2005 Feb; 20: 81–91.

Smith P K, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N . Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008; 49: 376–385.

Lyznicki J M, McCaffree M A, Robinowitz C B . Childhood bullying: implications for physicians. Am Fam Physician 2004; 70: 1723–1728.

Schwartz D, Dodge K A, Coie J D . The emergence of chronic peer victimization in boys' play groups. Child Dev 1993; 64: 1755–1772.

Berstein J Y, Watson M W . Children who are targets of bullying: a victim pattern. J Interpers Violence 1997; 12: 483–498.

Kumpulainen K, Räsänen E, Henttonen I . Children involved in bullying: psychological disturbance and the persistence of the involvement. Child Abuse Negl 1999; 23: 1253–1262.

Due P, Holstein B E, Lynch J et al. Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: international comparative cross sectional study in 28 countries. Eur J Public Health 2005; 15: 128–132.

Kim Y S, Koh Y J, Leventhal B . School bullying and suicidal risk in Korean middle school students. Pediatrics 2005; 115: 357–363.

Bond L, Carlin J B, Thomas L, Rubin K, Patton G . Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ 2001; 323: 480–484.

Rigby K. Peer victimisation at school and the health of secondary school students. Br J Educ Psychol 1999; 69: 95–104.

Stevens V, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Oost P . Anti-bullying interventions at school: aspects of programme adaptation and critical issues for further programme development. Health Promot Int 2001; 16: 155–167.

Department for Education and Skills. Evaluation of the DFES anti-bullying pack. London: Department for Education and Skills, 2003.

Department for Education and Skills. Bullying: don't suffer in silence. An anti-bullying pack for schools. London: Department for Education and Skills, 2000.

Smith P K, Sharp S (eds). School bullying: insights and perspectives. London: Routledge, 1994.

Fekkes M, Pijpers F I, Verloove-Vanhorick S P. Effects of antibullying school program on bullying and health complaints. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006; 160: 638–644.

Fonagy P, Twemlow S W, Vernberg E, Sacco F C, Little T D . Creating a peaceful school learning environment: the impact of an antibullying program on educational attainment in elementary schools. Med Sci Monit 2005; 11: CR317–CR325.

Naylor P, Cowie H . The effectiveness of peer support systems in challenging school bullying: the perspectives and experiences of teachers and pupils. J Adolesc 1999; 22: 467–479.

Stevens V, Van Oost P, De Bourdeaudhuij I . The effects of an anti-bullying intervention programme on peers' attitudes and behaviour. J Adolesc 2000; 23: 21–34.

Dawkins J. Bullying in schools: doctors' responsibilities. BMJ 1995; 310: 274–275.

Department for Education. Bullying webpage. http://www.education.gov.uk/schools/pupilsupport/behaviour/bullying (accessed 4 May 2011).

Cunningham S J. The psychology of facial appearance. Dent Update 1999; 26: 438–443.

Shaw W C, Addy M, Ray C . Dental and social effects of malocclusion and effectiveness of orthodontic treatment: a review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1980; 8: 36–45.

Macgregor F C. Social and psychological implications of dentofacial disfigurement. Angle Orthod 1970; 40: 231–233.

Shaw W C. The influence of children's dentofacial appearance on their social attractiveness as judged by peers and lay adults. Am J Orthod 1981; 79: 399–415.

Shaw W C, Meek S C, Jones D S . Nicknames, teasing, harassment and the salience of dental features among school children. Br J Orthod 1980; 7: 75–80.

Secord P F, Backman C W . Malocculusion and psychological factors. J Am Dent Assoc 1959; 59: 931–938.

O'Brien K, Macfarlane T, Wright J et al. Early treatment for Class II malocclusion and perceived improvements in facial profile. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 135: 580–585.

Kerosuo H, Hausen H, Laine T, Shaw W C . The influence of incisal malocclusion on the social attractiveness of young adults in Finland. Eur J Orthod 1995; 17: 505–512.

Linn E L. Social meanings of dental appearance. J Health Hum Behav 1966; 7: 289–295.

Helm S, Kreiborg S, Solow B . Psychosocial implications of malocclusion: a 15-year follow-up study in 30-year-old Danes. Am J Orthod 1985; 87: 110–118.

Gosney M B. An investigation into some of the factors influencing the desire for orthodontic treatment. Br J Orthod 1986; 13: 87–94.

Polat Z S, Tacir IH . Restoring of traumatized anterior teeth: a case report. Dent Traumatol 2008; 24: e390–e394.

Gill D S, Jones S, Hobkirk J, Bassi S, Hemmings K, Goodman J . Counselling patients with hypodontia. Dent Update 2008; 35: 344–346, 348–350, 352.

Hunt O, Burden D, Hepper P, Stevenson M, Johnston C . Self-reports of psychosocial functioning among children and young adults with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2006; 43: 598–605.

Seehra J, Newton T, Dibiase A T . Bullying in orthodontic patients and its relationship to malocclusion, self-esteem and oral health related quality of life. London: King's College London, 2009. MSc Thesis.

Prove S A, Freer T J, Taverne A A . Perceptions of orthodontic appliances among grade seven students and their parents. Aust Orthod J 1997; 15: 30–37.

Phillips C, Beal K N . Self-concept and the perception of facial appearance in children and adolescents seeking orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod 2009; 79: 12–16.

Kenealy P, Frude N, Shaw W . An evaluation of the psychological and social effects of malocclusion: some implications for dental policy making. Soc Sci Med 1989; 28: 583–591.

O'Brien C, Benson P E, Marshman Z . Evaluation of a quality of life measure for children with malocclusion. J Orthod 2007; 34: 185–193.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seehra, J., Newton, J. & DiBiase, A. Bullying in schoolchildren – its relationship to dental appearance and psychosocial implications: an update for GDPs. Br Dent J 210, 411–415 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.339

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.339

This article is cited by

-

Pathways between verbal bullying and oral conditions among school children

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2023)

-

Prevalence of bullying in orthodontic patients and its impact on the desire for orthodontic therapy, treatment motivation, and expectations of treatment

Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics / Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie (2023)

-

Is there a relationship between malocclusion and bullying? A systematic review

Progress in Orthodontics (2020)

-

School bullying and traumatic dental injuries in East London adolescents

British Dental Journal (2014)