Key Points

-

Increases understanding of bite mark analysis.

-

Underlines the importance of appropriate evidence collection, management, preservation, analysis and interpretation.

-

Highlights the benefit of advancements in digital technology.

-

Emphasises the importance of exercising caution with opinions and conclusions.

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to give a brief overview of bite mark analysis: its usefulness and limitations. The study and analysis of such injuries is challenging and complex. The correct protocols for collection, management, preservation, analysis and interpretation of this evidence should be employed if useful information is to be obtained for the courts. It is now possible, with advances in digital technology, to produce more accurate and reproducible comparison techniques which go some way to preventing and reducing problems such as photographic distortions. Research needs to be continued to increase our knowledge of the behaviour of skin when bitten. However, when presented with a high quality bite mark showing good dental detail, and a limited, accessible number of potential biters, it can be extremely useful in establishing a link between the bitten person and the biter or excluding the innocent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The examination and analysis of bite marks is used in an attempt to scientifically link the dentition of a potential biter with a bite mark. The bite mark may be found on skin or some other material, and crime scenes must be thoroughly searched in order to find bitten objects that may link a biter to a crime scene: a bitten piece of cheese found at the murder scene, along with other evidence, helped secure a conviction of the murderer of three family members after a wedding in the UK in 1983. Bite mark evidence has been used with increasing frequency over the years, possibly due to raised awareness and recognition of such injuries (from a multidisciplinary approach), along with an increase in the number of domestic violence and abuse cases reported, many of which involve biting injuries.

Bite mark analysis methods have evolved over the years to give more reliable and reproducible results. However, the behaviour of skin and the underlying tissue during the dynamic biting process is still not clearly understood and caution with the interpretation of (and conclusions drawn from) these injuries is essential if this evidence is to be useful and acceptable to the courts. A few controversial cases involving biting injuries have emphasised the need for standardised protocols, appropriate training and carefully considered opinions and conclusions.

Some considerations

The complexity of biting injuries and their analysis and interpretation makes them a great challenge even for the most experienced forensic odontologist.1 Human bite marks can be found on the skin of the living or deceased, adult or child, victim or suspect. They can also be found on inanimate objects such as foods,2 wood, leather, or other substances. Beware the self-inflicted bite and the so-called amorous or 'love' bite.

Sexual assaults, fights, homicides and abusive incidents often result in biting injuries and the necessity to involve the forensic odontologist. Sometimes it may be necessary to differentiate a bite caused by a human dentition from that caused by an animal. For example, worried neighbours called the police when they saw an 18-month-old child in the next door garden, covered in bruises. On examination, five of the injuries were confirmed as human bite marks. The child's mother and boyfriend said the bites must have been inflicted by the dog next door (a good example of the injury not being explained by the history given). Following bite mark analysis, the mother (and dog!) could be excluded from causing the bites; the boyfriend could not.

A bite mark may be defined as a representative pattern left in an object or tissue by the dental structures of an animal or human. This article will limit discussion to those bites caused by the human dentition on skin.

It is essential to ensure that evidence relating to the injury is documented, collected, preserved, analysed and interpreted following appropriate protocols and using scientifically accepted techniques. Teamwork is essential for the correct management of evidence from these injuries and may involve police, crime scene investigators, pathologists, forensic odontologists and DNA personnel. Legal teams may present the evidence to the courts, as this type of evidence is admissible in several countries. Conclusions must be carefully considered and free from personal bias, and may support or refute a conviction; getting it wrong may lead to a miscarriage of justice and incarceration of an innocent person (or release of the guilty): not acceptable.

Case 1: going back in time – the Gordon Hay case

On 6 August 1967, the distraught parents of a teenager reported the she had not come home that night. The following day the body of 15-year-old Linda Peacock was found in a cemetery in Biggar, near Edinburgh, Scotland. She had been struck with a blunt object and then strangled with a rope, her clothes were disturbed but she had not been raped. On her right breast was an oval shaped bruise, recognised and confirmed as a human bite mark which showed certain irregularities of the dentition, including pitting of the canine biting edges. Linda's murder horrified both the police and the general public in this quiet village.

Investigating officers focused their attention on a nearby detention centre for young men. Dental impressions were taken from a number of residents and after careful examination, the results eventually indicated that the teeth of 17-year-old Gordon Hay (with canine pitting) had caused the bite mark. Other inmates confirmed that Hay had slipped out of the detention centre the night that the girl was murdered. Also, a witness saw a male and female at the cemetery gates that night: the girl matching the description of the deceased.

At his trial in 1968 the jury found the bite mark evidence convincing, and Hay was convicted of murder. Despite the defence wanting the bite mark evidence to be ruled inadmissible, it was allowed by the judge. Because of Hay's age (not yet 18), he was sentenced 'to be detained during her Majesty's pleasure'. Hay was the first person in the UK to be convicted by forensic dentistry and this case set an important precedent, paving the way for such evidence to be used in other cases of rape, assault, and murder.

The injury

Early decisions

If an injury has features that suggest that it could have been caused by biting it should be referred to a forensic odontologist as soon as possible to ensure that all relevant evidence is collected appropriately and contemporaneously. Unfortunately, the forensic odontologist may not become involved with the investigation in its early stages, and may have to rely on limited evidence collection presented some days, weeks, or months (sometimes even years) after the incident. With the passage of time, healing may have occurred and in some cases medical intervention may have destroyed or obscured possible tooth marks (Fig. 1). However, even at a later date, valuable information may still be available if good quality scaled photographs of the injury have been taken. The transient nature of bite marks in the living (and in perishable substances) means that the investigation team needs to respond quickly and understand the basic requirements of the forensic odontologist, if valuable information is not to be lost. Early involvement of the forensic odontologist for discussion/advice on the potential forensic significance of a confirmed bite mark will determine what is to be done to maximise the quality of evidence collection.

Recognition of bite marks

Initial considerations include whether the injury is a bite mark and if so, whether it has been caused by human biting: can we exclude the dog next door?

Human bite marks may present as diffuse or specific bruising, abrasions or lacerations, through to complete avulsion of tissue – and often in combination. They usually comprise two opposing (facing) U-shaped arches that may be separated by open spaces, or as a ring of marks. Bites may show individual marks that reflect the characteristics of the contacting surfaces of the teeth. Central bruising is often present and is caused by compression (positive pressure) of the soft tissues between the teeth. Additional detail may be caused by the palatal/lingual surfaces of teeth imprinting the soft tissues.

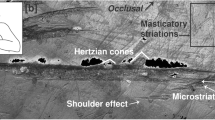

Marks from several of the upper front teeth and lower front teeth are usually found in the bite mark, but variations can and do occur: premolars and molars may be involved, there may be a partial bite mark caused by one arch (often the lower), one or a few teeth, or teeth from one side of the jaw only. Often, the lower arch creates the most noticeable injury, perhaps explainable because the smaller lower teeth, in comparison to the uppers, have a reduced surface area and stress (force exerted by unit area) is inversely related to surface area. Likewise, with the same biting force a dentition with fewer teeth will inflict more stress on tissue. The dynamic nature of the biting process means that marks made by the teeth scraping across the skin may also be present. There may be multiple bites at separate locations or they may overlap, making interpretation difficult (Fig. 2).

Differential diagnosis

To further complicate the investigation, other objects that can leave a circular or elliptical injury have sometimes been mistaken for bite marks (for example, marks made by ECG electrodes, door knobs and heel prints), and should be excluded after careful consideration. The current and past medical history of the bitten person may be of vital importance: some conditions of the skin may mimic bite marks, for example pityriasis rosea, and beware the medical condition that may predispose to bruising, such as liver disease or primary haematological disorders. It is important to distinguish pattern marks made by animal or insect predation (on the deceased) from those made by humans, and to understand postmortem skin changes that could cause confusion. Dark and freckled skins may camouflage a biting injury.

Case 2: Ted Bundy and the bite mark

Theodoure Robert 'Ted' Bundy, born on November 24 1946, murdered numerous young women in various parts of the United States between 1974 and 1978. He is thought to have murdered at least 30, but the actual total remains unknown. He would usually bludgeon his victims before strangling them and often engaged in rape and necrophilia. Some victims were decapitated with a hacksaw. All the victims were white females, mostly college students, of middle class backgrounds and almost all were between 15-25 years of age. However, his last victim was a 12-year-old girl that he abducted from school.

In order to gain the trust of his victims and lure them to his car, he often pretended to be injured and need assistance, or impersonated an authority figure; others were attacked in their bedrooms while they slept. He left some survivors who helped to identify him. Arrested in Salt Lake City in 1975, he escaped from prison twice, enabling him to continue his killing spree.

While still on the run in Florida, he murdered two more college students (and injured three more women) before being arrested again in February 1978. Marks on the buttock and breast of one of the young women were identified as bite marks, one having sufficient detail for the forensic dentist to link the injury to Bundy. This compelling dental evidence helped secure a conviction (before salivary DNA use) and was the first time that bite mark evidence entered the courts of Florida.

Bundy was sentenced to death and languished on death row for years giving out bits of information about the whereabouts of the remains of some of his undiscovered victims. He was executed on January 24 1989 aged 42.

Anatomical distribution of bite marks

Human bite marks have been recorded on most anatomical parts of the body. It has been noted that the bite location may vary depending on the type of crime, the sex of the bitten person and age of the victim.3 Studies show that females are bitten more often than males: frequent sites are the breast, arms and legs during sexual attacks. Males are commonly bitten on the arms, shoulders and back.4 Hands and arms are commonly bitten when a victim is attempting defence actions.

In an informal survey conducted by the author in the UK, there was general agreement with the above results but also a high number of biting injuries were recorded on the face and general head and neck area of both children and adults. Dental practitioners and team members must remain vigilant for such injuries – bites are often a component of non-accidental injury to children (this will be covered in article 5 in this series). Thorough examination is necessary to reveal any/all potential biting injuries and it is important that medical colleagues are trained to recognise and respond to such injuries.

A high percentage of cases involve multiple bites. A study in the USA found that 40% of bite mark victims had more than one bite,5 and this correlates well with the author's own findings. Table 1 shows the sites bitten in a personal study of 112 bites randomly selected (including multiple bite cases).

Evidence collection protocols (in brief)

Early recognition and action is necessary to make the most of the dental evidence: healing may occur and marks may quickly fade or change (in both the living and the dead). It is important to follow evidence collection protocols so that nothing is overlooked; it is important to get it right the first time because there may not be another opportunity.

1) Bitten person

Evidence collected from the victim does not usually involve informed consent, but it is prudent to explain your intentions and record consent, just in case. It is extremely important that the bite mark is photographed correctly to avoid photographic distortions, and this is best undertaken by a skilled photographer (Fig. 3) working with the forensic dentist.

2) Potential biter

Video imaging may be useful in addition to digital/conventional photography. Photographic techniques are also continually evolving in order to capture images of the injury that are not visible to the naked eye, including alternate light imaging; reflective (long wavelength) ultraviolet and infrared. All evidence should be appropriately collected, documented, labelled and preserved, with a clear chain of custody.

Comparisons

New techniques and developments in digital technology have significantly changed the approach to bite mark analysis, enabling a more precise and detailed recording of the marks and ensuring more accurate and reproducible comparison techniques, thus preventing and reducing problems such as photographic distortions.8 The use of appropriate software (such as Adobe Photoshop) allows for standardisation of technique with clear audit trails.

Technique

Using the above method, physical correspondence between the bite mark and biter's dentition can be evaluated and relevant conclusions reached.8 However, conclusions are still dependent on the skills and experience of the forensic dentist and an understanding of the biomechanical properties of skin and the underlying tissue. Most forensic dentists agree that most bites do not possess sufficient detail to positively identify just one individual, but it may be useful to the investigation to include or exclude a certain person from having caused the bite mark.

Case 3

A baby (and a toddler belonging to a friend) were left in the care of a teenage male babysitter. The parent arrived home to find the baby had patterned bruises to the face, arm and leg – the babysitter was blamed. These bruises were confirmed as human bite marks. However, the bites were very small, and individual tooth marks were consistent with deciduous teeth. Although the mother of the toddler refused to allow examination of her child, the babysitter was definitely innocent of causing the injuries, but several beers and an iPod may have lessened his ability to intervene!

It is the responsibility of the forensic dentist to follow ethical and professional codes, to analyse and interpret the evidence carefully and maintain the competencies for this work. Incorrect or misleading conclusions cause catastrophic consequences.

Case 4: a little girl is murdered

A three-year-old girl was taken from her bed in the middle of the night on May 3 1992 in Mississippi. Her mother's boyfriend, Kennedy Brewer, was in the house at the time and was arrested in connection with her disappearance. Her body was found in a pond close to the house two days later. At autopsy, marks on her skin were noted, examined by a forensic odontologist and identified as 19 human bite marks. Brewer was convicted of her murder in March 1995 and imprisoned.

Brewer always maintained his innocence and in 2001, while Brewer was on death row, DNA samples from the little girl's body (taken post-conviction) were matched to another person; a retrial never materialised and so Brewer stayed in prison. In 2006 the Innocence Project requested that the evidence be reviewed, including the dental evidence. Members of the reviewing dental committee agreed that the injuries were not human bites marks. Considerable research, at the request of the Innocence Project, by a forensic entomologist showed that the injuries were consistent with bites from aquatic predation. The collection of all this evidence led to the arrest of the real murderer who subsequently confessed. Brewer was exonerated in 2008.

Saliva, DNA and bacteria

Saliva can be identified by the presence of amylase in a sample, or by microscopic examination with appropriate histological staining. Identification of buccal epithelial cells indicates a saliva stain and lighting techniques can be used to search for saliva stains. It can be determined that the saliva sample is from a human source and it is well known that saliva is a good source of DNA.

Swabs of the bitten area of skin should be taken before the area is cleaned or washed and as soon after the injury was inflicted as possible, because DNA degrades over time and in the presence of extreme heat, decomposition, UV light, seawater etc. The double swab technique9 is used to maximise the amount of DNA collected and samples are submitted for analysis as soon as possible. Physical analysis of the patterned biting injury and biological analysis of the DNA may give double confirmation of the identity of the biter. However, there have been cases where the DNA evidence contradicts the dental bite mark opinion, leading to controversy.

The presence of saliva from the potential biter on and around the bite site may be of particular use if he or she has refused to have dental impressions taken, or when the bite mark shows insufficient detail to be of great evidential value. The presence or absence of clothing (Fig. 4) may be an important consideration – is there saliva present for DNA analysis (or punctures in the fabric) that could support the confirmation of a biting injury?

Streptococci can be isolated from the mouths of most humans and are genotypically extremely diverse.10 It has been demonstrated that large numbers of oral bacteria of the genus Streptococcus can be recovered from recently inflicted experimental bite marks on human skin and matched to isolates recovered from the teeth of the biter.11 These findings are supported by research using an arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (AP-PCR) technique, enabling larger numbers of oral bacteria to be rapidly analysed. This approach may assist with bite mark analysis, especially when the DNA of the biter cannot be recovered.12 Findings also indicate that some of the predominant streptococcal genotypes are retained on the teeth of the biter for prolonged periods of time (in the absence of antimicrobial treatment). This finding may be useful when there is a delay (weeks or months) in finding a potential biter, but relies on the appropriate collection and storage of bacteria samples from the bite site. Research is ongoing.

Caution!

So far so good... but difficulties arise because bite mark analysis is based on the assumptions that:

Studies of the dentition in large populations demonstrate that the size, shape and pattern of the biting surfaces of the upper and lower front teeth within the dental arches are specific to that individual. It should, therefore, be possible to produce an identifiable pattern that may be reproduced on skin (or other material). Significant variability exists in the human dentition,13 but does it create a unique dental profile, or is the problem the transfer of the pattern to skin?

How much dental detail is recorded in the bite pattern on the skin varies between cases. However, skin is a visco-elastic material and does not always accurately record dental detail when bitten. The behaviour of skin during the dynamic biting process is not completely understood, but there are many variables that may cause distortions, such as:

Only a few studies have addressed factors that can cause skin distortion.14 Recently, research from the USA on cadavers has shown that 'no two bites are visibly or measurably identical when dental models were used to inflict bites both parallel and perpendicular to skin tension lines (Langer lines) and with the limbs in different positions.'15 However, consistent distortional trends were observed. It was noted that 'when loose elastic tissue is bitten: mesial to distal width increased, there was flattening of the angles of rotation and an elongation of the inter-canine width. As the tissue became stiffer, the reverse effect was seen' (Fig. 5). Another important finding was that when stress on tissues was varied, a combination of these changes was observed relating to individual teeth. The surface area of the dentition, the relative height of individual teeth and the rate and length of time of applied force also played an important role in skin distortion.16 These studies, although on cadaver skin, may help us to understand the complexities of skin behaviour during the biting process and explain discrepancies in the bite pattern in relation to the dentition. However, caution should be used for definitive statements of correlation.

Conclusions

In this current climate, techniques and methodologies must be scientifically robust with regard to reliability, reproducibility and validity. Therefore, it is important that the forensic dental associations, societies, organisations and individuals around the world involved in this subject attempt to standardise procedures and terminology for bite mark work, and introduce some form of accreditation, mentoring, peer review and revalidation for those undertaking bite mark analysis. The American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO) has put considerable (and ongoing) work into this subject, endeavouring to increase the quality and reliability of bite mark analysis and evidence. The British Association for Forensic Odontology (BAFO) is also taking similar steps.

It can be appreciated that bite mark analysis involves much more than simply 'matching' the pattern made by the teeth of a potential suspect with the marks left on skin, and requires a competent and extremely careful approach. When there is high quality bite mark evidence and where all probable suspects can be examined (closed population), and if appropriate techniques are followed and distortions reduced and explained, then bite mark analysis can be of value in establishing a link between the bitten person and potential biter.17 However, when compared with DNA analysis, where the evidential significance of a match is determined by established statistical methods, much more high quality research is needed for bite mark analysis to remain acceptable to the scientific and judicial world.

The consequences of inappropriate and inaccurate bite mark conclusions may lead to a miscarriage of justice: a grave responsibility.

Further reading

Bowers C M. Forensic dental evidence: an investigator's handbook. 1st ed. San Diego, USA: Elsevier, 2004.

Dorion R B J (ed). Bitemark evidence. New York: Marcel Dekker (CRC Press), 2005.

Johansen R J, Bowers C M. Digital analysis of bite mark evidence. Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Forensic Imaging Services, 2003.

Herschaft E E, Alder M E, Ord D K, Rawson R D, Smith E S (eds). Manual of forensic odontology. 4th ed. New York: American Society of Forensic Odontology, 2006.

References

Sweet D, Pretty I A . A look at forensic dentistry – part 2: teeth as weapons of violence – identification of bite mark perpetrators. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 415–418.

Sweet D, Hildebrand D P . Saliva from cheese bite yields DNA profile of burglar: a case report. Int J Legal Med 1999; 112: 201–203.

Pretty I A, Sweet D . Anatomical locations of bite marks and associated findings in 101 cases from the United States. J Forensic Sci 2000; 45: 812–814.

Freeman A J, Senn D R, Arendt D M . Seven hundred seventy-eight bite marks: analysis by anatomic location, victim and biter demographics, type of crime, and legal disposition. J Forensic Sci 2005; 50: 1436–1443.

Vale G I, Noguchi T T . Anatomical distribution of human bitemarks in a series of 67 cases. J Forensic Sci 1983; 28: 61–69.

Dorion R B. Preservation and fixation of skin for ulterior scientific evaluation and courtroom presentation. J Can Dent Assoc 1984; 50: 129–130.

Dorion R B. Transillumination in bite mark evidence. J Forensic Sci 1987; 32: 690–697.

Johansen R J, Bowers C M . Digital analysis of bite mark evidence. Santa Barbara, CA, USA: Forensic Imaging Services, 2003.

Sweet D, Lorente J A, Lorente M, Vlaenquela A, Villaneuva E . An improved method to recover saliva from human skin: the double swab technique. J Forensic Sci 1997; 42: 320–322.

Alam S, Brailsford S R, Whiley R A, Beighton D . PCR based methods for genotyping viridans group streptococci. J Clin Microbiol 1999; 37: 2772–2776.

Borgula L M, Robinson F G, Rahimi M et al. Recovery of oral bacteria from experimental bite marks. J Forensic Odontostomatol 2003; 21: 23–30.

Rahimi M, Heng N C K, Kieser J A, Tompkins G R . Genotypic comparison of bacteria recovered from human bite marks and teeth using arbitrarily primed PCR. J Appl Microbiol 2005; 99: 1265–1270.

Kieser J A, Bernal V, Waddell J N, Raju S . The uniqueness of the human anterior dentition: a geometric morphometric analysis. J Forensic Sci 2007; 52: 671–677.

Sheasby D R, MacDonald D G . A forensic classification of distortion in human bitemarks. Forensic Sci Int 2001; 122: 75–78.

Bush M A, Miller R G, Bush P J, Dorion B J . Biomechanical factors in human dermal bitemarks in a cadaver model. J Forensic Sci 2009; 54: 167–176.

Bush M A, Thorsrud K, Miller R G, Dorion R B J, Bush P J . The response of skin to applied stress: investigation of bitemark distortion in a cadaver model. J Forensic Sci 2010; 55: 71–76.

Senn D. A critical look at the forensic value of bite mark analysis. Forensic Odontology News 2007; Winter: 1, 6–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hinchliffe, J. Forensic odontology, part 4. Human bite marks. Br Dent J 210, 363–368 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.285

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.285

This article is cited by

-

The “hypopigmented” bitemark: a clinical and histologic appraisal

International Journal of Legal Medicine (2023)

-

Superimposed polygonal approximation analysis comparing 2D photography and 3D scanned images of bite marks on human skin

Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences (2021)