Key Points

-

Methotrexate is increasingly being used in the management of chronic inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis.

-

Dental practitioners are likely to encounter paitients taking long-term methotrexate therapy.

-

Methotrexate has the ability to cause oral ulceration and dental practioners should be alert to this possible adverse effect.

Abstract

Methotrexate is well established in the drug treatment of various neoplastic diseases. More recently it has become increasingly used as a once-weekly, low-dose treatment of disorders such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical trials have shown its effectiveness in these conditions and it is likely that dentists will encounter patients taking this drug in general dental practice. Oral ulceration can occur as a side effect of methotrexate therapy. This may be due to lack of folic acid supplementation or overdosage due to confusion regarding its once-weekly regime. Illustrations of these problems, which have initially presented in a dental setting, are given. Important drug interactions of methotrexate relevant to dentistry are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Methotrexate is an antimetabolite and immune modulating drug. When taken at high dose its use is well established as a chemotherapeutic agent in the treatment of malignant diseases, including leukaemia, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and a number of solid tumours.

Methotrexate has also found another role when taken at lower doses in the control of chronic inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis.1,2 There has also been recent interest in the use of methotrexate in the treatment of Crohns disease and ocular disease.3,4 For these non-malignant conditions it is usually given in a once weekly dose of up to 25 mg.2 In rheumatoid disease the drug has proved popular as an alternative to systemic steroids and azathioprine as it is effective whilst lacking the extensive side effects of systemic steroids. Methotrexate may also improve survival in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, largely through reducing cardiovascular mortality.5

The success of long-term low dose methotrexate treatments means that more patients in the community are taking this drug. Dental practitioners are increasingly likely to encounter patients taking methotrexate and awareness of its implications within dentistry is important. As illustrations of its potential to cause adverse oral effects, we report here two cases of methotrexate related oral ulceration, which presented in a dental setting.

Case report 1

A 63-year-old woman was referred to the unit of oral medicine by her dental practitioner. She complained of painful generalised oral ulceration for 10 days. She had no previous history of oral ulceration.

The medical history showed the patient to have rheumatoid arthritis. She was otherwise well with no known allergies. She did not smoke and drank alcohol rarely. Her medications on presentation comprised: methotrexate, prednisolone, folic acid (5 mg per week), ibuprofen, diclofenac and celecoxib. She had commenced a once weekly dose of methotrexate 10 mg 6 months previously. She had recently visited Poland to stay with relatives, and approximately 1 month ago, whilst on this trip, had consulted a local physician as her rheumatoid arthritis had worsened. She had been advised to increase her once weekly 10 mg methotrexate dose to once daily (weekly total 70 mg); she was also prescribed prednisolone (8 mg day) and diclofenac (100 mg day) for symptomatic relief.

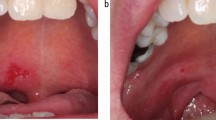

Extra-oral examination showed ulceration of the lips. Intra-oral examination showed multiple shallow areas of ulceration in the floor of the mouth, buccal and labial mucosa and soft palate, all on a background of an erythematous mucosa (Fig. 1).

The clinical impression was of oral mucositis secondary to methotrexate overdosage.

Arrangements were made for the patient to see her rheumatologist the following day. She was advised not to take any more methotrexate in the meantime and prescribed chlorhexidine gluconate (Corsodyl®) and benzydamine hydrochloride (Difflam®) mouthwashes for symptomatic relief.

At review after 5 weeks the patient's symptoms had abated and the ulceration had resolved entirely over the intervening period. The patient was now complying with the correct drug regime (methotrexate 10 mg weekly, folic acid 5 mg weekly) and her rheumatoid arthritis remained well controlled.

Case report 2

A 75-year-old man self presented at the dental casualty unit before being seen in the oral medicine unit. He gave a two-month history of painful oral ulceration affecting the tongue, buccal mucosa, lower lip and throat. He had no previous history of oral ulceration.

The medical history revealed that he had suffered with rheumatoid arthritis for 30 years. He had commenced taking methotrexate 2.5 mg once weekly 4 years earlier; this dosage having been slowly increased to a once weekly dose of 17.5 mg, 6 months before presentation. He also had a heart murmur and long standing iron deficiency anaemia. He had no known allergies. He did not smoke nor drink alcohol. His other medications consisted of: prednisolone (10 mg per day for 5 years), omeprazole (Losec®), diclofenac with misoprostol (Arthrotec®), risedronate sodium (Actonel®) and ferrous sulphate. A recent peripheral blood count had shown a haemoglobin of 12.6 g dl−1 (MCV raised at 99fl, white cell differential normal). Serum ferritin and vitamin B12 levels were within the normal range. Folate levels could not be measured as the laboratory used a microbiological assay which is inaccurate in the presence of methotrexate.

On examination intra-orally, several superficial shallow ulcers were seen ranging from 3-10 mm in diameter, affecting the non-keratinised buccal, labial and tongue mucosa (Fig. 2).

A provisional diagnosis of methotrexate related oral ulceration was made.

On closer questioning it became apparent that he was taking his methotrexate incorrectly (namely 2.5 mg daily rather than a once weekly dosage of 17.5 mg) and he had not been taking folic acid supplementation. As treatment, the patient was prescribed topical betamethasone mouthwash (500 μg dissolved in 10 ml water), and contact with his rheumatologist was established.

At review, two weeks later, the patient reported some symptomatic relief with the mouthwash. Following a consultation with his rheumatologist, he was now taking methotrexate 17.5 mg in a weekly dose and folic acid 5 mg once weekly.

Subsequent review after four weeks showed resolution of the oral ulceration and a concomitant reduction in oral symptoms. The patient's rheumatic arthritis remained well controlled on the once weekly methotrexate and folic acid dosing regime. Six months later, the patient remained free of oral ulceration.

Discussion

Severe oral ulceration, as a component of oral mucositis, is a common feature of the short term, high dose methotrexate regimes used in the treatment of malignant disease. Such mucositis is difficult to manage and causes much distress in affected patients.6 Oral ulceration in the low dose methotrexate treatment regimes of rheumatoid arthritis is less common. The risk of a high dosage occurring accidentally however, is increased by the unusual dosage regime. Once weekly, rather than daily dosing, helps reduce the risk of hepatotoxicity but it can create confusion and lead to overdosage if the drug is inadvertently taken daily.7 In such cases oral mucositis can be expected, as illustrated in the first case presented here. Because of the frequency of this error occurring, the National Patient Safety Agency has recently made various recommendations to try to reduce the frequency of adverse events in patients taking low dose methotrexate.8

As well as dosage error, interacting drugs can also affect serum methotrexate levels.2 Of dental relevance, aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have the ability to reduce methotrexate excretion by their effect on renal tubules. The British National Formulary advises that the methotrexate dose should be carefully monitored if aspirin or other NSAIDs are given concurrently.2 Patients should also be advised to avoid self medication with over-the-counter aspirin or ibuprofen. Methotrexate excretion is also reduced by penicillin, increasing the risk of toxicity. Nitrous oxide increases the anti-folate effects of methotrexate and their concurrent use, such as in inhalational sedation, should be avoided.2

The action of methotrexate in psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis remains uncertain, although inhibitory effects on cytokines may be important. In cancer therapy it prevents normal cell division. Methotrexate is an inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase, an enzyme that reduces folate to an active form where it acts as a co-factor for the production of nucleic acids essential for DNA synthesis. This effect on reducing DNA formation and cell turnover is responsible for both the therapeutic effect and the more common side effects. Methotrexate mostly affects cells undergoing rapid turnover, including mucosa and bone marrow, hence myelosuppresion and mucositis are among the more common reported adverse reactions.1

Myelosuppression, in the forms of leucopenia or thrombocytopenia has been found in approximately 8% of rheumatoid patients on an average of 10.7 mg of methotrexate per week.9 Pancytopenia has also been recorded on low dose methorexate, including in patients who have subsequently died.10 A much higher incidence of marrow suppression is seen in renal impairment and with high dosages. Hepatotoxicity is reported as affecting between 3% to 25% of psoriasis patients on long-term methotrexate therapy.1 Rheumatoid arthritis patients tend to take slightly lower doses and they are concomitantly less likely to suffer hepatotoxicity. Renal damage is a problem at high dose, but rare at rheumatoid disease modifying levels. Despite the serious nature of its side effects, methotrexate has one of the lowest side effect profiles of the disease modifying drugs and has been shown to have one of the lowest discontinuation rates due to toxicity in this group, 15% in 6 months.9

The side effect of methotrexate of most significance to dentists is that of mucositis and oral ulceration. This is generally dose dependant. As already noted, high dose methotrexate used in the treatment of malignant disease commonly causes mucositis. The reported levels of stomatitis or ulceration affecting the oral mucosa in studies of low dose methotrexate however, are wide ranging. A study by Kremer et al.11 found up to 55% of patients reported episodes of mouth soreness over a 90 month period while taking low dose methotrexate. A further retrospective questionnaire study by Ince et al.12 found a prevalence of 37.2% of self-reported stomatitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis taking methotrexate, compared with 19.5% in a control group. This study also found that of those suffering oral lesions while taking methotrexate, 15.7% had greater than four mouth lesions and 31.5% had lesions lasting longer than 1 week. In both of these studies no folic acid supplementation was given. Singh et al.9 looked at the toxicity profiles of all the disease modifying anti-rheumatics and found the methotrexate group gave the highest levels of mucosal ulceration, 87 events per 1,000 patient years (mean dose 10.7 mg per week). Of the other drugs in this group, oral gold (76 events) gave the next highest level followed by intramuscular gold (55 events), D-penicillamine (38 events), azathioprine (35 events) and hydroxychloroquine (8 events).

It has been known for some time that predisposition to many of the adverse effects of methotrexate therapy such as mucositis, include factors such as folate deficiency and concomitant use of other antifolate drugs.13 Efforts have hence been made to prevent some of the adverse effects whilst preserving the therapeutic benefit of methotrexate by using folate supplementation. There are two physiological circulating folates: folic acid and folinic acid. They have different actions in the cell. Methotrexate competes with folinic acid for entry into the cell at the cell folate receptors whilst folic acid does not. Folinic acid, as a reduced folate co-enzyme, can participate in DNA and RNA synthesis without the need for reduction by dihydrofolate reductase; folic acid however is dependant on reduction by this enzyme. Folinic acid (or the synthetic equivalent leucovirin) can also displace methotrexate from dihydrofolate reductase thus creating a supply of fully reduced intracellular folate. Due to these mechanisms, folinic acid can be used as a 'rescue therapy' to counteract severe methotrexate induced mucositis or myelosuppresion.

Supplementation with folinic acid to reduce adverse effects in rheumatoid patients has been tried and has been shown to be most useful when given 24 hours following methotrexate to minimise inhibiting the therapeutic action of methotrexate.14 Folic acid supplementation has also been shown to be effective in reducing the adverse effects of methotrexate, with decreased loss of therapeutic effect and less precision required for dose scheduling compared with folinic acid.15 It is also cheaper than folinic acid. A recent meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials indicated a 79% reduction in mucosal and gastrointestinal side effects when folic acid supplementation was used in patients on low dose methotrexate.16 Folic acid supplementation has thus become favoured however there is debate whether prophylactic administration of folic acid supplements should be given to all patients on methotrexate or whether it is reasonable to await the emergence of adverse effects if folate depletion becomes a problem (such as illustrated by the second case presented here).17 The dose at which folic acid should be prescribed is also unclear. The BNF suggests 5 mg folic acid weekly for patients with mucosal or gastro-intestinal side effects of methotrexate.2 A recent meta-analysis indicated no major difference in terms of side effects on using low (<5 mg) or high dose (>5 mg) weekly folic acid supplementation although the number of trials available for analysis was low.16 There is some evidence that indicates that the folic acid dose can be increased up to a 3:1 folic acid: methotrexate ratio (eg 30 mg folic acid: 10 mg methotrexate/weekly) as treatment for adverse effects, with no evidence of any diminished therapeutic effect of methotrexate.18

Low dose methotrexate for the control of chronic disabling disease is increasingly being used. In general it is a safe and effective drug, however there are implications for dentists. Oral ulceration may be related to dosage error or folate deficiency and these issues should be clarified in patients who present with oral ulceration whilst taking methotrexate.

References

Olsen EA . The pharmacology of methotrextate. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 25: 306–318.

British National Formulary. 45. London: BMA, RPS, 2003.

Schroder O, Stein J . Low dose methotrexate in inflammatory bowel disease: current status and future directions. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 530–537.

Smith JR, Rosembaum JT . A role for methotrexate in the management of non-infectious orbital inflammatory disease. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 1220–1224.

Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F . Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet 2002; 359: 1173–1177.

Knox JJ, Puodziunas ALV, Feld R . Chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: prevention and management. Drugs Aging 2000; 17: 257–267.

West SG . Methotrexate toxicity. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1997; 23: 883–915.

Major S . UK introduces measures to reduce errors with methotrexate. Br Med J 2003; 327: 70.

Singh G, Fries JF, Williams CA, Zatarain E, Spitz P, Bloch A . Toxicity profiles of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1991; 18: 188–194.

Sosin M, Handa S . Low dose methotrexate and bone marrow suppression. Br Med J 2003; 326: 266–267.

Kremer JM, Phelps CT . Long-term prospective study of the use of methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1992; 35: 138–145.

Ince A, Yazici Y, Hamuryudan V, Yazici H . The frequency and clinical characteristics of methotrexate (MTX) oral toxicity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): A masked and controlled study. Clin Rheumatol 1996; 15: 491–494.

Jackson R . Biological effects of folic acid antagonists with antineoplastic activity. Pharmacol Ther 1984; 25: 61–82.

Shirozky JB, Neville C, Esdaile JM et al. Low-dose methotrexate with leucovirin (folinic acid) in the management of rheumatoid arthritis: results of a muticenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 1993; 36: 795–803.

Stewart KA, Mackenzie AH, Clough JD, Wilke WS . Folate supplementation in methotrexate-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1991; 20: 332–338.

Ortiz Z, Shea B, Suarez-Almazor M, Moher D, Wells GA, Tugwell P . The efficacy of folic acid and folinic acid in reducing methotrexate gastrointestinal toxicity in rheumatoid arthritis. A metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol 1998; 25: 36–43.

Endresen GKM, Husby G . Folate supplementation during methotrexate treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 2001; 30: 129–134.

Morgan SL, Baggott JE, Vaughan WH et al. Supplementation with folic acid during methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121: 833–841.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Deeming, G., Collingwood, J. & Pemberton, M. Methotrexate and oral ulceration. Br Dent J 198, 83–85 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811972

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811972

This article is cited by

-

Adipokines and periodontal markers as risk indicators of early rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study

Clinical Oral Investigations (2021)

-

Clinicopathological analysis of 34 Japanese patients with EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer

Modern Pathology (2020)

-

EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcers: a presentation of two cases and a brief literature review

Surgical and Experimental Pathology (2019)

-

Anti-Toxoplasma antibodies in Egyptian rheumatoid arthritis patients

Rheumatology International (2017)

-

Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcer: a case report and systematic review of the literature

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2015)