Key Points

-

Aesthetics is neither an art nor a science, but a fusion of the two.

-

Ancient Greeks postulated basic concepts in an endeavour to quantify beauty, including the Divine Proportion, symmetry, unity and harmony.

-

The Gestalt Principle is a psychological theory, which can be used for unifying aesthetics in a logical manner.

Key Points

ANTERIOR DENTAL AESTHETICS

-

1

Historical perspective

-

2

Facial perspective

-

3

Dento-facial perspective

-

4

Dental perspective

-

5

Gingival perspective

-

6

Psychological perspectivet*

*Part 6 available in the BDJ Book

Abstract

The purpose of this series is to convey the principles governing our aesthetic senses. Usually meaning visual perception, aesthetics is not merely limited to the ocular apparatus. The concept of aesthetics encompasses both the time — arts such as music, theatre, literature and film, as well as space — arts such as paintings, sculpture and architecture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The first point of contention regarding aesthetics is its definition. Is it an art or a science? Science has long propagated allusions to objective critical analysis, which are now unfounded and vehemently refuted. In reality, any scientific investigation is tainted by individual, philosophical and cultural biases. Art, on the other hand, has been always been portrayed as subjective, romantic and empathetic. Whilst fundamental aesthetic principles are based on Greek and Roman mathematics, nevertheless, artists conceived aesthetics for creating pleasing paintings that touched our inner souls. One can undoubtedly decipher the dichotomy of aesthetics, attracting endless debate by both scientific and artistic communities. Put succinctly, science asks 'how?', while art asks 'why?'

It is difficult segregating dental aesthetics into distinct units, since all variables are interdependent and interrelated. However, for the sake of discussion, this series compartmentalises dental aesthetics into compositions or perspectives, according to the viewing distance. Starting with the facial perspective, and zooming closer to the dento-facial, dental and gingival (Figs 1, 2, 3 to 4). Finally, the last part, on the 'psychological perspective', proposes a psychological link between cerebral perception and the dentition.

Before embarking on individual dental perspectives, it is necessary to define fundamental guidelines, which contribute to aesthetic appraisal.

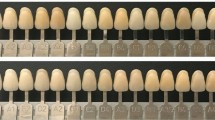

Colour, form and lines

The link between colour and form can be traced to the Greek and Egyptian empires. In fact, much of Renaissance and Medieval thinking has been plagiarised from the ancient Greek era. For a detailed analysis of the relationship between form and colour, the writings of the colour theorist Johannes Itten (1888–1967) are invaluable. For the purpose of dentistry, a few essential principles require consideration. Firstly, in any composition, colour is the predominant force, taking precedence over form, angles and lines. The difficulty assessing the value (brightness component) for a shade prescription is because the eyes are distracted by the colour (hue and chroma components) of the tooth.

Secondly, any form can be created from the three basic shapes of a circle, triangle and square. These geometric shapes were, and are, associated with religious, mystical and esoteric connotations. For example, in ancient times, the triangle stood for impending danger, a symbol that is used today for warning signs on roads. The circle represented celestial spirituality, inferring tranquillity and egalitarianism, while a square denoted sturdiness, after the solid base of the Egyptian pyramids. The maxillary anterior teeth are a fusion of these basic shapes, a topic that is discussed further in the 'Dental perspective' article (Figs 5, 6 to Fig. 7).

A line can be perceived, without actually been drawn. The oral cavity has ample examples of these phenomena. Consider the incisal edges of the maxillary teeth, often referred to as the incisal plane. It is the curvaceous arrangement of the teeth that implies a plane, even though none is actually present. Further examples are the curves of Wilson and Spee (Fig. 8). The direction of lines can also create optical illusions. Prominent vertical lines on the facial surface of an anterior tooth will infer a longer tooth, while distinct horizontal lines have the opposite effect, (wide and short tooth length).

Divine Proportion

Proportion in a composition is analogous to harmonies in music. When proportions of even harmonies on a musical scale are adjusted equally on both sides, the result is a rhythmic and harmonious auditory perception. Similarly, repeated or recurring ratios in the visual arena are viewed as artistic and aesthetically pleasing, e.g. the repeated width ratios of the maxillary anterior teeth.

Ancient Greeks were preoccupied with seeking methods by which beauty could be quantified and predictably reproduced by artisans and artists. Their goal was to discover arithmetic simplicity, which could signify beauty and harmony. This led Pythagoras in 530 BC, accompanied by his followers, to seek refuge in Croton in southern Italy. The objective of this clandestine gathering was to discover a mathematical solution for what was perceived as beautiful or ugly. The answer proposed by the Pythagoreans' was the Golden Number, represented by the Greek symbol, Δ [(Δ5-1) ÷ 2]. The reciprocal of Δ is 0.618 and has been termed the Golden or Divine Proportion. Objects, animate or inanimate, whose features or details conform to this ratio, are perceived as having innate beauty. It is important to distinguish innate or absolute beauty from subjective beauty. Absolute beauty implies that if two objects, one conforming to the Golden Proportion and the other not in this ratio, are presented to a group of individuals, 99% will affirm that the object with the Golden Proportion is beautiful. The second type is subjective beauty, which is a psychological concept, colloquially referred to as 'beauty in the eyes of the beholder'.

The affirmation that the Golden Proportion signifies beauty has been exemplified by its ubiquitous prevalence in both the plant and animal kingdoms, e.g. the logarithmic spiral. The beauty of flowers, or attractiveness of faces, has been attributed to features, which conform to a ratio of 0.618. Architects and sculptors in antiquity exploited the Golden Proportion for creating buildings, e.g. the Parthenon in Athens, and statues having eternal appeal (Fig. 9). Numerous artists have also slavishly used the Golden Proportion to create masterpieces. For example, Piero della Francesca's 'The Baptism of Christ' and 'The Flagellation' and illustrations by Leonardo da Vinci for Luca Pacioli's 'Divina Proportione', all demonstrate rigid adherence to this ratio.

The Golden or Divine Proportion is true for emulating Olympian beauty, but in nature, such beauty is neither prevalent, nor desirable. If all animals and plants displayed such exactness, we would be surrounded by clones. However, even if a plant or animal does not display features conforming to such dogmatic dimensions, its beauty is not compromised. What is the reason for this apparent disparity? To create diversity and individuality, repeated or recurring proportions are more significant than a specific ratio. Consequently, the ratio for beauty of 0.618 signifies an ideal. Nevertheless, other ratios, e.g. 0.577 or 0.8 are also perceived as aesthetic, with the proviso that there is repetition, or recurrence in a given composition.

Symmetry

Symmetry is defined as static or dynamic. Static symmetry is evidenced by repetition in inanimate objects such as crystals or contrived arrangements (Fig. 10). Dynamic (radiating) symmetry refers to repeated proportions in animate, living or vital beings, such as flowers (Fig. 11). This monumental discovery was attributed to the American architect Jay Hambidge, and concurrently by the English scientist Sir D'Arcy Thompson in the 1920s. The art deco movement of the 1930s, epitomised by the Chrysler building in New York, is a classic example where dynamic symmetry has been extensively used. The significance of dynamic symmetry provided the missing link between nature, buildings, crafts, and works of art dating back to ancient Greece. Analysis of Greek architecture and craftwork confirm identical repeated ratios and proportions found in the natural world. This was affirmation that geometry alone was inadequate for explaining natural and artistic beauty, and aesthetic elucidation was only apparent when combined with the principles of dynamic symmetry.

Unity and Harmony

In addition to divine proportion and dynamic symmetry, unity in a composition is achieved by incorporating balancing forces as well as a dominant key element. It is important to realise that teeth are arranged with tectonic spacing. Tectonic refers to an arrangement that is both functional and aesthetic. For example, the maxillary anterior teeth are arranged with specific proportions and repeating ratios not only for aesthetic appeal, but also for proper function during protrusion of the mandible, the upper laterals are shorter, thereby avoiding interference with the mandibular canines (Figs 12 and 13). There are two types of visual forces requiring consideration. The first are cohesive forces, which provide unity and harmony, e.g. two parallel objects (Fig. 14) or an encircling frame (lips bordering the anterior teeth). The opposite are segregative forces, which convey tension and interest, e.g. objects that bisect each other in a perpendicular arrangement (Fig. 15). Segregative forced are essential for avoiding monotony and adding curiosity and variety to a composition.

Balance ensures equilibrium and stability. This is similar to a weighing scale, with both sides having equal weight distribution. In a pictorial form, the forces should be balanced for conveying stability and equilibrium (Fig. 16). Finally, the protagonist or salient point of a picture should be dominant. This is achieved by size, position or colour. A larger object, compared to surrounding elements, conveys prominence. In dentistry, two types of dominance are evident: individual or segmental. Individual dominance is related to single units, e.g. wide and prominent maxillary central incisors. Segmental dominance, usually preferred by patients, is dominance of a group of objects, e.g. prominence of the maxillary anterior sextant, often portrayed by the fashion & cosmetic industries and haute couture magazines. An item, whose position is central to the optical axis, is perceived as the centre of attention, and hence dominates a composition. Colour is another method exploited for creating dominance, especially complementary colours of an object and its background, e.g. blue object with a yellow background (Fig. 17).

The Gestalt Principle

This theory combines the above principles of aesthetics in a coherent and logical manner. Dr Max Wertheimer initiated the Gestalt theory of psychology in Germany around 1912, and put succinctly, its definition is “the whole is different from the sum of its parts”. For example, the teeth, made of organic and inorganic matter, have a profound impact on an individual's personality and well-being, which is significantly remote from the substance from which they are constructed. In concurrence with the Pragnanz law, the Gestalt theory implies that the mind organises the outside world so that it can come to terms with it. This involves creating meaning, stability, balance and security. These concepts allow the observer to achieve a better object-background (figure-ground) relationship by encapsulating the following four constituents:

-

Proximity

-

Similarity

-

Continuity

-

Closure.

Incorporating the above entities in a composition results in stability and harmony. Also, applying the above four constituents for an aesthetic makeover creates a good Gestalt, enhancing psychological appraisal. The four constituents of a good Gestalt are discussed below.

Proximity facilitates association, linking, grouping, learning, and therefore adds interest. Segregation, on the other hand, implies disassociation, complexity, isolation, un-grouping and leads to frustration, rejection or boredom. A dental example is teeth arranged adjacent to each other, without diastemae, avoids detachment and aloofness. However, a degree of segregation is essential for mitigating repetitiveness.

Similarity ensures objects have similar form, colour, position and line angles, e.g. teeth with similar shade, form and arch alignment.

Continuity ensures progression, e.g. recurring or repeated ratios from the maxillary incisors to the canines.

Closure assures cohesiveness, such as a frame or border, e.g. lips surrounding the teeth (Fig. 18).

Closure is particularly important for our satisfaction (visual and otherwise) and learning process. If conclusions are vague, ambiguous or open-ended, the Zeigarnick effect is prevalent. The latter is when a task or sequence is incomplete, the short-term memory recall is superior, but the message is lost after about twenty-four hours. The result is that the mind is left in a state of confusion, detachment, and if unable to resolve these conflicts [by conjuring the missing sequence or stages]; it forgets them to avoid mental tension and frustration. Closure is highly dependant on the id, if an individual is confident, assertive and self-assured (greater coping abilities), they are likely either to dismiss or 'come to terms' with an incomplete event. Conversely, an anxious, timid and ambivalent personality (low coping abilities), is unlikely to resolve the predicament, resulting in consternation. To complicate matters further, an individual's coping ability varies at a given time or place. Nevertheless, closure, as a psychological concept, is extremely important for mental stability by ensuring equilibrium between our conscious and unconscious states of mind. A dental analogy is teeth of different shades, irregular form and erratic positions causing disharmony and visual dissatisfaction, and therefore preventing closure.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted some aesthetic principles relevant to clinical practice. In the rest of the series, these principles will be used for achieving a pleasing outcome for aesthetic dental treatment. The next part, 'Facial Perspective' discuses ideal facial features as well as analsing other factors relevant to this perspective.

References

Hegel GWF . Philosophy of History. New York: Collier, 1905.

Lombardi R . Visual perception and denture esthetics. J Prosthet Dent, 1973; 29: 352–382.

Plato . Republic. c 400 BC

Ehrenzweig A . The Hidden Order of Art. Berkley: University of California Press, 1971

Ahmad I . Digital and Conventional Photography: A Practical Clinical Manual. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing, 2004 (in print).

Stroebel L, Todd H, Zakia R . Visual Concepts for Photographers. New York: Focal Press, 1980.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, I. Anterior dental aesthetics: Historical perspective. Br Dent J 198, 737–742 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812411

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812411

This article is cited by

-

Outside the box

British Dental Journal (2005)