Key Points

-

An accurate diagnosis of the patient's condition is essential before an appropriate treatment plan can be formulated for that individual.

-

A logical approach to clinical examination should be adopted.

-

A high quality long-cone parallel radiograph is mandatory before commencing root canal treatment, and should be carefully examined to obtain all possible information.

-

Root canal treatment may not be the most appropriate therapy, and treatment plans should take into account not only the expected prognosis but also the patient's dental condition, expectations and wishes.

Key Points

Endodontics

-

1

The modern concept of root canal treatment

-

2

Diagnosis and treatment planning

-

3

Treatment of endodontic emergencies

-

4

Morphology of the root canal system

-

5

Basic instruments and materials for root canal treatment

-

6

Rubber dam and access cavities

-

7

Preparing the root canal

-

8

Filling the root canal system

-

9

Calcium hydroxide, root resorption, endo-perio lesions

-

10

Endodontic treatment for children

-

11

Surgical endodontics

-

12

Endodontic problems

Abstract

As with all dental treatment, a detailed treatment plan can only be drawn up when a correct and accurate diagnosis has been made. It is essential that a full medical, dental and demographic history be obtained, together with a thorough extra-oral and intra-oral examination. This part considers the classification of diseases of the dental pulp, together with various diagnostic aids to help in determining which condition is present, and the appropriate therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The importance of correct diagnosis and treatment planning must not be underestimated. There are many causes of facial pain and the differential diagnosis can be both difficult and demanding. All the relevant information must be collected; this includes a case history and the results of both a clinical examination and diagnostic tests. The practitioner should be fully conversant with the prognosis for different endodontic clinical situations, discussed in Part 12. Only at this stage can the cause of the problem be determined, a diagnosis made, the appropriate treatments discussed with the patient and informed or valid consent obtained.

Case history

The purpose of a case history is to discover whether the patient has any general or local condition that might alter the normal course of treatment. As with all courses of treatment, a comprehensive demographic, medical and previous dental history should be recorded. In addition, a description of the patient's symptoms in his or her own words and a history of relevant dental treatment should be noted.

Medical history

There are no medical conditions which specifically contra-indicate endodontic treatment, but there are several which require special care. The most relevant conditions are allergies, bleeding tendencies, cardiac disease, immune defects or patients taking drugs acting on the endocrine or CNS system. If there is any doubt about the state of health of a patient, his/her general medical practitioner should be consulted before any endodontic treatment is commenced. This also applies if the patient is on medication, such as corticosteroids or an anticoagulant. An example of the particulars required on a patient's folder is illustrated in Table 1.

Antibiotic cover has been recommended for certain medical conditions, depending upon the complexity of the procedure and the degree of bacteraemia expected, but the type of antibiotic and the dosage are under continual review and dental practitioners should be aware of current opinion. The latest available edition of the Dental Practitioners' Formulary1 should be consulted for the current recommended antibiotic regime. However, when treating patients who may be considered predisposed to endocarditis, it may be advisable to liaise with the patient's cardiac specialist or general medical practitioner. Not all patients with cardiac lesions require antibiotic prophylaxis, and such regimes are not generally supported by the literature.2 However, if it is agreed that the patient is at risk, they would normally be prescribed the appropriate prophylactic antibiotic regime, and should be advised to report even a minor febrile illness which occurs up to 2 months following root canal treatment. Prior to endodontic surgery, it is useful to prescribe aqueous chlorhexidine (2%) mouthwash.

Patient's complaints

Listening carefully to the patient's description of his/her symptoms can provide invaluable information. It is quicker and more efficient to ask patients specific, but not leading, questions about their pain. Examples of the type of questions which may be asked are given below.

-

1

How long have you had the pain?

-

2

Do you know which tooth it is?

-

3

What initiates the pain?

-

4

How would you describe the pain?

-

5

Sharp or dull

-

6

Throbbing

-

7

Mild or severe

-

8

Localised or radiating

-

9

How long does the pain last?

-

10

Does it hurt most during the day or night?

-

11

Does anything relieve the pain?

It is usually possible to decide, as a result of questioning the patient, whether the pain is of pulpal, periapical or periodontal origin, or if it is non-dental in origin. As it is not possible to diagnose the histological state of the pulp from the clinical signs and symptoms, the terms acute and chronic pulpitis are not appropriate. In cases of pulpitis, the decision the operator must make is whether the pulpal inflammation is reversible, in which case it may be treated conservatively, or irreversible, in which case either the pulp or the tooth must be removed, depending upon the patient's wishes.

If symptoms arise spontaneously, without stimulus, or continue for more than a few seconds after a stimulus is withdrawn, the pulp may be deemed to be irreversibly damaged. Applications of sedative dressings may relieve the pain, but the pulp will continue to die until root canal treatment becomes necessary. This may then prove more difficult if either the root canals have become infected or if sclerosis of the root canal system has occurred. The correct diagnosis, once made, must be adhered to with the appropriate treatment.

In early pulpitis the patient often cannot localise the pain to a particular tooth or jaw because the pulp does not contain any proprioceptive nerve endings. As the disease advances and the periapical region becomes involved, the tooth will become tender and the proprioceptive nerve endings in the periodontal ligament are stimulated.

Clinical examination

A clinical examination of the patient is carried out after the case history has been completed. The temptation to start treatment on a tooth without examining the remaining dentition must be resisted. Problems must not be dealt with in isolation and any treatment plan should take the entire mouth and the patient's general medical condition and attitude into consideration.

Extra-oral examination

The patient's face and neck are examined and any swelling, tender areas, lymphadenopathy, or extra-oral sinuses noted, as shown in Figure 1.

Intra-oral examination

An assessment of the patient's general dental state is made, noting in particular the following aspects (Fig. 2).

-

Standard of oral hygiene.

-

Amount and quality of restorative work.

-

Prevalence of caries.

-

Missing and unopposed teeth.

-

General periodontal condition.

-

Presence of soft or hard swellings.

-

Presence of any sinus tracts.

-

Discoloured teeth.

-

Tooth wear and facets.

Diagnostic tests

Most of the diagnostic tests used to assess the state of the pulp and periapical tissues are relatively crude and unreliable. No single test, however positive the result, is sufficient to make a firm diagnosis of reversible or irreversible pulpitis. There is a general rule that before drilling into a pulp chamber there should be two independent positive diagnostic tests. An example would be a tooth not responding to the electric pulp tester and tender to percussion.

Palpation

The tissues overlying the apices of any suspect teeth are palpated to locate tender areas. The site and size of any soft or hard swellings are noted and examined for fluctuation and crepitus.

Percussion

Gentle tapping with a finger both laterally and vertically on a tooth is sufficient to elicit any tenderness. It is not necessary to strike the tooth with a mirror handle, as this invites a false-positive reaction from the patient.

Mobility

The mobility of a tooth is tested by placing a finger on either side of the crown and pushing with one finger while assessing any movement with the other. Mobility may be graded as:

1 — slight (normal)

2 — moderate

3 — extensive movement in a lateral or mesiodistal direction combined with a vertical displacement in the alveolus.

Radiography

In all endodontic cases, a good intra-oral parallel radiograph of the root and periapical region is mandatory. Radiography is the most reliable of all the diagnostic tests and provides the most valuable information. However, it must be emphasised that a poor quality radiograph not only fails to yield diagnostic information, but also, and more seriously, causes unnecessary radiation of the patient. The use of film holders, recommended by the National Radiographic Guidelines3 and illustrated in Part 4, has two distinct advantages. Firstly a true image of the tooth, its length and anatomical features, is obtained (Fig. 3), and, secondly, subsequent films taken with the same holder can be more accurately compared, particularly at subsequent review when assessing the degree of healing of a periradicular lesion.

A radiograph may be the first indication of the presence of pathology (Fig. 4). A disadvantage of the use of radiography in diagnosis, however, can be that the early stages of pulpitis are not normally evident on the radiograph.

If a sinus is present and patent, a small-sized (about #40) gutta-percha point should be inserted and threaded, by rolling gently between the fingers, as far along the sinus tract as possible. If a radiograph is taken with the gutta-percha point in place, it will lead to an area of bone loss showing the cause of the problem (Fig. 5).

Pulp testing

Pulp testing is often referred to as 'vitality' testing. In fact, a moribund pulp may still give a positive reaction to one of the following tests as the nervous tissue may still function in extreme states of disease. It is also, of course, possible in a multirooted tooth for one root canal to be diseased, but another still capable of giving a vital response. Pulp testers should only be used to assess vital or non-vital pulps; they do not quantify disease, nor do they measure health and should not be used to judge the degree of pulpal disease. Pulp testing gives no indication of the state of the vascular supply which would more accurately indicate the degree of pulp vitality. The only way pulpal blood-flow may be measured is by using a Laser-Doppler Flow Meter, not usually available in general practice!

Doubt has been cast on the efficacy of pulp testing the corresponding tooth on the other side of the mid-line for comparison, and it is suggested that only the suspect teeth are tested.

Electronic

The electric pulp tester is an instrument which uses gradations of electric current to excite a response from the nervous tissue within the pulp. Both alternating and direct current pulp testers are available, although there is little difference between them. Most pulp testers manufactured today are monopolar (Fig. 6).

As well as the concerns expressed earlier about pulp testing, electric pulp testers may give a false-positive reading due to stimulation of nerve fibres in the periodontium. Again, posterior teeth may give misleading readings since a combination of vital and non-vital root canal pulps may be present. The use of gloves in the treatment of all dental patients has produced problems with electric pulp testing. A lip electrode attachment is available which may be used, but a far simpler method is to ask the patient to hold on to the metal handle of the pulp tester. The patient is asked to let go of the handle if they feel a sensation in the tooth being tested.

The teeth to be tested are dried and isolated with cotton wool rolls. A conducting medium should be used; the one most readily available is toothpaste. Pulp testers should not be used on patients with pacemakers because of the possibility of electrical interference.

Teeth with full crowns present problems with pulp testing. A pulp tester is available with a special point fitting which may be placed between the crown and the gingival margin. There is little to commend the technique of cutting a window in the crown in order to pulp test.

Thermal pulp testing

This involves applying either heat or cold to a tooth, but neither test is particularly reliable and may produce either false-positive or false-negative results.

Heat

There are several different methods of applying heat to a tooth. The tip of a gutta-percha stick may be heated in a flame and applied to a tooth. Take great note that hot gutta-percha may stick fast to enamel, and it is essential to coat the tooth with vaseline to prevent the gutta-percha sticking and causing unnecessary pain to the patient. Another method is to ask the patient to hold warm water in the mouth, which will act on all the teeth in the arch, or to isolate individual teeth with rubber dam and apply warm water directly to the suspected tooth. This is explored further under local anaesthesia.

Cold

Three different methods may be used to apply a cold stimulus to a tooth. The most effective is the use of a −50°C spray, which may be applied using a cotton pledget (Fig. 7). Alternatively, though less effectively, an ethyl chloride spray may be used. Finally, ice sticks may be made by filling the plastic covers from a hypodermic needle with water and placing in the freezing compartment of a refrigerator. When required for use one cover is warmed and removed to provide the ice stick. However, false readings may be obtained if the ice melts and flows onto the adjacent tissues.

Local anaesthetic

In cases where the patient cannot locate the pain and routine thermal tests have been negative, a reaction may be obtained by asking the patient to sip hot water from a cup. The patient is instructed to hold the water first against the mandibular teeth on one side and then by tilting the head, to include the maxillary teeth. If a reaction occurs, an intraligamental injection may be given to anaesthetise the suspect tooth and hot water is then again applied to the area; if there is no reaction, the pulpitic tooth has been identified. It should be borne in mind that a better term for intraligamental is intra-osseous, as the local anaesthetic will pass into the medullary spaces round the tooth and may possibly also affect the proximal teeth.

Wooden stick

If a patient complains of pain on chewing and there is no evidence of periapical inflammation, an incomplete fracture of the tooth may be suspected. Biting on a wood stick in these cases can elicit pain, usually on release of biting pressure.

Fibre-optic light

A powerful light can be used for transilluminating teeth to show interproximal caries, fracture, opacity or discoloration. To carry out the test, the dental light should be turned off and the fibre-optic light placed against the tooth at the gingival margin with the beam directed through the tooth. If the crown of the tooth is fractured, the light will pass through the tooth until it strikes the stain lying in the fracture line; the tooth beyond the fracture will appear darker.

Cutting a test cavity

When other tests have given an indeterminate result, a test cavity may be cut in a tooth which is believed to be pulpless. In the author's opinion, this test can be unreliable as the patient may give a positive response although the pulp is necrotic. This is because nerve tissues can continue to conduct impulses for some time in the absence of a blood supply.

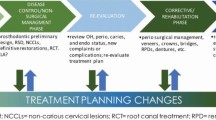

Treatment planning

Having taken the case history and carried out the relevant diagnostic tests, the patient's treatment is then planned. The type of endodontic treatment chosen must take into account the patient's medical condition and general dental state. The indications and contra-indications for root canal treatment are given below and the problems of re-root treatment discussed. The treatment of fractured instruments, perforations and perio-endo lesions are discussed in subsequent chapters.

It should be emphasised here that there is a considerable difference between a treatment plan and planning treatment. Figure 8 shows a radiograph of a patient with a severe endodontic problem. A diagnosis of failed root canal treatments, periapical periodontitis (both apically and also associated with a perforation of one root), and failed post crowns could be made. A treatment plan for this patient may be orthograde re-root canal treatment, with repair of the perforation, followed by the provision of new posts and cores, and crowns.

However, success in this case may depend upon the correct planning of treatment. For example, what provisional restorations will be used during the root canal treatment, and during the following re-evaluation period. Temporary post-crowns have been shown to be very poor at resisting microleakage.4 The provision of a temporary over denture, enabling the total sealing of the access cavities, would seem an appropriate alternative, but if this has not been properly planned for, problems may arise and successful treatment may be compromised.

Indications for root canal treatment

All teeth with pulpal or periapical pathology are candidates for root canal treatment. There are also situations where elective root canal treatment is the treatment of choice.

Post space

A vital tooth may have insufficient tooth substance to retain a jacket crown so the tooth may have to be root-treated and restored with a post-retained crown (Fig. 9).

Overdenture

Decoronated teeth retained in the arch to preserve alveolar bone and provide support or removable prostheses must be root-treated.

Teeth with doubtful pulps

Root treatment should be considered for any tooth with doubtful vitality if it requires an extensive restoration, particularly if it is to be a bridge abutment. Such elective root canal treatment has a good prognosis as the root canals are easy to access and are not infected. If the indications are ignored and the treatment deferred until the pulp becomes painful or even necrotic, access through the crown or bridge will be more restricted, and treatment will be significantly more difficult, with a lower prognosis.5

Risk of exposure

Preparing teeth for crowning in order to align them in the dental arch can risk traumatic exposure. In some cases these teeth should be electively root-treated.

Periodontal disease

In multirooted teeth there may be deep pocketing associated with one root or the furcation. The possibility of elective devitalisation following the resection of a root should be considered (see Part 9).

Pulpal sclerosis following trauma

Review periapical radiographs should be taken of teeth which have been subject to trauma. If progressive narrowing of the pulp space is seen due to secondary dentine, elective root canal treatment may be considered while the coronal portion of the root canal is still patent. This may occasionally apply after a pulpotomy has been carried out. However, Andreasen6 refers to a range of studies that show a maximum of 16% of sclerosed teeth subsequently cause problems, and the decision over root canal treatment must be arrived at after full consultation with the patient. If the sclerosing tooth is showing the classic associated discoloration the patient may elect for treatment, but otherwise the tooth may better be left alone (Fig. 10).

Contra-indications to root canal treatment

The medical conditions which require special precautions prior to root canal treatment have already been listed. There are, however, other conditions both general and local, which may contra-indicate root canal treatment.

General

Inadequate access

A patient with restricted opening or a small mouth may not allow sufficient access for root canal treatment. A rough guide is that it must be possible to place two fingers between the mandibular and maxillary incisor teeth so that there is good visual access to the areas to be treated. An assessment for posterior endodontic surgery may be made by retracting the cheek with a finger. If the operation site can be seen directly with ease, then the access is sufficient.

Poor oral hygiene

As a general rule root canal treatment should not be carried out unless the patient is able to maintain his/her mouth in a healthy state, or can be taught and motivated to do so. Exceptions may be patients who are medically or physically compromised, but any treatment afforded should always be in the best long-term interests of the patient.

Patient's general medical condition

The patient's physical or mental condition due to, for example, a chronic debilitating disease or old age, may preclude endodontic treatment. Similarly, the patient at high risk to infective endocarditis, for example one who has had a previous attack, may not be considered suitable for complex endodontic therapy.

Patient's attitude

Unless the patient is sufficiently well motivated, a simpler form of treatment is advised.

Local

Tooth not restorable

It must be possible, following root canal treatment, to restore the tooth to health and function (Fig. 11). The finishing line of the restoration must be supracrestal and preferably supragingival.

An assessment of possible restorative problems should always be made before root canal treatment is prescribed.

Insufficient periodontal support

Provided the tooth is functional and the attachment apparatus healthy, or can be made so, root canal treatment may be carried out.

Non-strategic tooth

Extraction should be considered rather than root canal treatment for unopposed and non-functional teeth.

Root fractures

Incomplete fractures of the root have a poor prognosis if the fracture line communicates with the oral cavity as it becomes infected. For this reason, vertical fractures will often require extraction of the tooth while horizontal root fractures have a more favourable prognosis (Fig. 12).

Internal or external resorption

Both types of resorption may eventually lead to pathological fracture of the tooth. Internal resorption ceases immediately the pulp is removed and, provided the tooth is sufficiently strong, it may be retained. Most forms of external resorption will continue (see Part 9) unless the defect can be repaired and made supragingival, or arrested with calcium hydroxide therapy.

Bizarre anatomy

Exceptionally curved roots (Fig. 13), dilacerated teeth, and congenital palatal grooves may all present considerable difficulties if root canal treatment is attempted. In addition, any unusual anatomical features related to the roots of the teeth should be noted as these may affect prognosis.

Re-root treatment

One problem which confronts the general dental practitioner is to decide whether an inadequate root treatment requires replacement (Fig. 14). The questions the operator should consider are given below.

-

1

Is there any evidence that the old root filling has failed?

-

Symptoms from the tooth.

-

Radiolucent area is still present or has increased in size.

-

Presence of sinus tract.

-

Does the crown of the tooth need restoring?

-

Is there any obvious fault with the present root filling which could lead to failure?

Practitioners should be particularly aware of the prognosis of root canal re-treatments. As a rule of thumb, taking the average of the surveys reported in the endodontic literature (see Part 12) suggests a prognosis of 90–95% for an initial root canal treatment of a tooth with no radiographic evidence of a periradicular lesion. When such a lesion is present prognosis will fall to around 80–85%, and the longer the lesion has been present the more established will be the infection, treatment (ie removal of that infection from the entire root canal system) will be more difficult and the prognosis significantly lower. The average reported prognosis for re-treatment of a failed root canal filling of a tooth with a periradicular lesion falls to about 65%.

The final decision by the operator on the treatment plan for a patient should be governed by the level of his/her own skill and knowledge. General dental practitioners cannot become experts in all fields of dentistry and should learn to be aware of their own limitations. The treatment plan proposed should be one which the operator is confident he/she can carry out to a high standard.

References

Dental Practitioners' Formulary 2000/2002. British Dental Association. BMA Books, London

Scully C, Cawson RA . Medical problems in dentistry. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, p74, 1998.

National Radiographic Protection Board. Guidance Notes for Dental Practitioners on the safe use of x-ray equipment. 2001. Department of Health, London, UK.

Fox K, Gutteridge DL . An in vitro study of coronal microleakage in root-canal-treated teeth restored by the post and core technique. Int Endod J 1997; 30: 361–368.

Ørstavik D . Time-course and risk analysis of the development and healing of chronic apical periodontitis in man. Int Endod J 1996; 29: 150–155.

Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM . Chapter 9 in Textbook and colour atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth. 3rd Ed, Denmark, Munksgard 1994.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carrotte, P. Endodontics: Part 2 Diagnosis and treatment planning. Br Dent J 197, 231–238 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811612

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811612

This article is cited by

-

Top tips for identifying endodontic case complexity: part 1

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Laser-Doppler microvascular flow of dental pulp in relation to caries progression

Lasers in Medical Science (2022)

-

Top tips for mastering endodontics at university

BDJ Student (2021)

-

The precision of case difficulty and referral decisions: an innovative automated approach

Clinical Oral Investigations (2020)

-

What do we (do not) know about the use of cone beam computed tomography in endodontics? A thematic series with a call for scientific evidence

Evidence-Based Endodontics (2017)