Key Points

-

Good communication is essential between primary and secondary care.

-

The use of a referral proforma from GDPs to hospital clinicians can increase the quality of information shared about patients.

-

Provided of clear clinical information can avoid potential delays.

Abstract

Aim To assess the quality improvement of new patient referrals to a restorative department comparing a standard referral proforma and a normal referral letter.

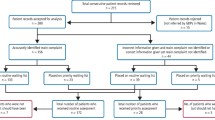

Design A prospective analysis of a consecutive sample of all referral letters and replied proforma until a total of 100 had been achieved.

Method The study covered the period from November 2000 to June 2001. Once the letters and corresponding proforma were matched, they were compared for data capture and hence quality.

Results There was an increase in 29.3% of information provided. Specific categories of data showed high increases such as patient's telephone number, relevant medical history, treatment already given, recorded signs and symptoms, urgency of the referral and whether treatment or advice was requested.

Conclusions In this study, the quality of restorative referral increased with the use of a referral proforma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

With clinical governance and quality high on the agenda in the hospital and public domain, this study was designed to investigate the quality of information provided by referring general dental practitioners.

The importance of the referral letter has always been essential for good communication between general practitioners and hospital consultants. This is reflected in both the medical and dental literature.1,2,3 Most of the time, the referral letter and the letter of response are the only forms of communication between the referrer and the hospital.4 Since the referral letter is the main source of information regarding the patients' clinical problem4,5 a clear and concise letter is essential to enable efficient and effective management of the patient.3

Various authors have commented on the standard of referral letters ranging from reasonable to good. McAndrew et al.4 found that they were 'of a reasonable standard' in their survey to 200 consultants in all dental specialities whilst Hammond et al.5 felt that 100 letters from general dental practitioners to orthodontic consultants were of 'good quality'.

In order to prioritise and direct referrals to the appropriate clinic, information on clinical details and medical history, as well as administrative details are necessary. Zakrewska reported that referrals to an oral medicine clinic were lacking in clinical detail with no attempt being made at a diagnosis.3 This was also found in referrals to an eye hospital.6 They also reported that the medical histories were insufficient and therefore they proposed a standard referral proforma for general medical practitioners to use.

Recommendations for what a referral letter should contain have been the subject of many papers.2,7 Clear recommendations have not, however, been made in the dental specialities although McAndrew4 and Zakrzewska3 both made suggestions for information needed in a referral letter to a dental consultant. Zakrzewska suggested that the referral should contain administrative details, clinical findings and relevant medical history. However, McAndrew showed that consultants in dentistry felt that the only essential information required in a referral was administrative detail.

There have been attempts by the medical specialities to formalise and standardise the structure of referral using letter formats and problem lists.8,9 A recent study on the effect of standardised referrals to a periodontal clinic showed an increase in the information provided with the use of a referral proforma, when compared with a normal referral letter.10

Some general dental practitioners set up a general referral letter with 'delete as required' sections and tick boxes to allow referral to all dental hospital specialties. One study looked at this and reported a decrease in the clarity of information provided.5

Method

Following discussion with junior and senior staff within the department, a list of the minimum data required on a referral letter specific for restorative dentistry was established and can be seen in Table 1.

All letters received in the department of restorative dentistry are assessed by a consultant and then directed towards the appropriate clinic. Any letters that lacked enough data to allow prioritisation were photocopied and the original letter was returned to the referrer with a letter of explanation and the referral proforma inviting them to use it.

The period covered by the study was from November 2000 to June 2001. This is the length of time it took to match up the required number of original letters with proformas.

All letters that presented with little more than 'please see and treat' were returned to the referring practitioner together with the proforma and an accompanying letter asking for more information. The proforma and the accompanying letter used in the survey can be seen in Figures 1 and 2.

When the completed referral proforma was returned to the department, it was matched up with the photocopy of the original letter.

The number of itemised responses on both the original referral letter and the proforma were totalled and compared.

Results

The time interval from receipt of the initial letter and the matching proforma varied from 1-8 weeks. This will be presented in a separate report.

There were 115 letters that were returned to sender, which were not matched up with a proforma. One hundred matched letters were subjected to data analysis. These letters comprised 2.4% of all referrals for the year; estimated at 4,200 in total, or 350 letters per month (in 2001).

The age range of the patients included in the study was 10-81 with a mean age of 47 years. The sample included a fairly even distribution of males (42%) and females (58%).

The referral sample was generally based on single cases (ie 66 different general dental practitioners were asked to provide more information on single letters in a given time period). There were 14 general dental practitioners who referred multiple cases ranging from 2-9 patients.

The number of items included in the proformas and the referral letters were totalled separately and compared to give a broad measure of improvement. A complete table comparing the performance of proformas and letters can be seen in Table 2 This shows a 29.3% increase in completed fields and data provided. From Table 2 it is clear that there was little change between the letter and the proforma in the following areas:

-

Date of referral

-

Patient's name

-

Patient's date of birth

-

Patient's address.

There were a number of areas that did not improve despite the use of the proforma. These were:

-

Indication of smoking

-

Duration of symptoms

-

Inclusion of radiographs

-

Referrals to another hospital

An improvement was seen in the provision of information in the following areas:

-

Patient's telephone number

-

Relevant medical history

-

Diagnosis made

-

Treatment already received

-

Signs recorded

-

Urgent request with explanation

-

Whether referred for advice or treatment

-

Symptoms recorded

Discussion

The present study allowed comparisons to be made between the information provided by a referral letter and then by a referral proforma regarding the same patient.

Overall, the use of a referral proforma resulted in an increase in the information provided by general dental practitioners referring to a dental hospital. This concurs with the findings of Snoad et al.10

Good communication between referring practitioners and hospitals has been accepted as essential in different areas of healthcare.1,2,3

A total of 80 general dental practitioners unknowingly took part in the study. This study does not wish to suggest that this is representative of all referring practitioners throughout North and East London. Neither does it aim to correlate the quality of the referral letter with the experience or qualifications of the referrer.

There was a delay of 1-8 weeks from receipt of the initial letter and the completed proforma. It is not possible to comment on this variation but the authors appreciate that this is an important area as the current emphasis is improving access to care. A possible explanation could be due to seasonal variation or holiday periods.

Over 50% (115) of letters returned to the referrer were not matched with a completed referral proforma. It may be that the use of the proforma helped to reduce the number of inappropriate referrals to the department. This study did not follow up to see if a more detailed letter was returned rather than the proforma. This area is interesting and is currently being investigated.

The overall standard of basic administrative details was good. This agrees with previous work.2,4,5 The patient's telephone number was recorded in less than half the total amount of referrals. There was an increase in this data once a proforma was used. A decrease in the date of referral and patient address was seen. Invariably, the original referral letter was stapled to the proforma when returned and it is reasonable to assume that the referrer felt it was not necessary to duplicate information. There was an increase in the provision of the date of birth too.

The referrers often completed their details well on the original referral letter. Again, on completion of the proforma, this information was left off in a number of cases. This can be attributed to the returning of the proforma with the initial referral letter and the understandable reluctance to duplicate work on their part.

Although other authors4 have suggested that good administrative information was sufficient for a referral to be accepted, the authors feel that additional information regarding symptoms and signs of clinical disease for example, should be included.

The use of the proforma increased the record of medical history by a large number. Again, the restorative department feel that this is important information unlike the 54% from the McAndrew et al.4 questionnaire to dental consultants working in the UK.4 In this study, a note of 'no relevant medical history' was recorded as positive since the medical history had been considered. The indication of smoking however, did not fair so well with only two replies being returned with an answer to this question. This raises certain issues with GDPs in regards to their perceived importance of smoking or their lack of a smoking history for a patient. This may have clinical relevance for prioritisation for patients with periodontal disease, for example.

Zakrewska,3 in her survey of 122 letters, showed that over 50% did not attempt to make a diagnosis. This behaviour was similar in this study but the use of the proforma demonstrated a two-fold increase in the number of referrers suggesting a diagnosis.

The diagnosis that was made by the referrer was recorded more frequently with the proformas. The signs and symptoms that were recorded by the referrer also increased compared with the original letters. The information for the duration of the symptoms did not increase very much even with the proforma prompts.

The largest increase in data that the proforma provided was the information for treatment already given. This increased by ten fold. Again it is especially useful for patients with periodontal disease or prosthetic patients to know what treatment has been attempted and hence making prioritisation easier.

Inclusion of radiographs increased only slightly perhaps indicating a general reluctance to send parts of a patient's record to hospital. The data concerning referral to other hospitals hardly increased, as this is not a common occurrence.

There were increases in the request for categorising referrals as 'urgent' and 'treatment or advice'. Again this can help with prioritisation of the letter and the outcome for the patient after a consultation.

Individual cases did show that the proforma worked well in eliciting more and useful information. However, there were some cases that also illustrated little or no improvement. The authors are not naive in assuming that all information received is accurate. Referrers may include information that they know will guarantee acceptance of the letter regardless of whether this information is a true reflection of the clinical problem. It is the opinion of the authors that in providing a quality service with reduced waiting times, this type of behaviour will not occur. As a result of this study, a number of improvements could be made to increase the data capture and the accuracy of the study. The redesigning of the proforma, reworking some phrases into clearer questions such as 'does the patient smoke?' or 'have you referred the patient to another hospital?'. It may be a good idea to distribute the proformas amongst a number of practices for their use and compare these with another group of practices who continue to use the referral letter.

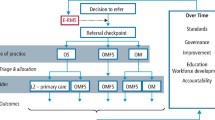

This study has highlighted the importance of communication between the referring general dental practitioner and the hospital. It shows that the use of a proforma for referrals can result in an increase in the quality and quantity of information provided regarding the patient. This can only lead to a more efficient and effective service. As suggested by Markiner et al. in 1988, it would be ideal to have an accepted standard for inclusion of information for restorative referrals across the country. Zakrewska has already taken this forward for oral medicine3 and since this study, a steering group has been set up with representation from the hospital dental services, community dental services, general dental services and the PCT. The group have agreed an acceptance criteria and a referral proforma for all dental hospital referrals.

References

Westerman RF, Hull FM, Bezemer PD, Gort G . A study of communication between general practitioners and specialists. Br J Gen Prac 1990; 40: 445–449.

Newton J, Eccles M, Hutchinson A . Communication between general practitioners and consultants: what should their letters contain? Br Med J 1992; 304: 821–824.

Zakrzewska JM . Referral letters-how to improve them. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 180–182.

McAndrew R, Potts AJC, McAndrew M, Adam S . Opinions of dental consultants on the standard of referral letters in dentistry. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 22–25.

Hammond M, Evans DR, Rock WP . A study of letters between general practitioners and consultant orthodontists. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 259–263.

Jones NP, Lloyd IC, Kwartz J . General practitioner referrals to an eye hospital: standard referral form. J Royal Soc Med 1990; 83: 770–772.

Marinker M, Wilken D, Metcalfe DH . Referral to hospital; can we do better? Br Med J 1988; 297: 461–464.

Lloyd BW, Barnett P . Use of problem lists in letters between hospital doctors and general practitioners. Br Med J 1993; 306: 247.

Rawal J, Barnett P, Lloyd BW . Use of structured letters to improve communication between hospital doctors and general practitioners. Br Med J 1993; 307:1044.

Snoad RJ, Eaton KA, Furniss JS, Newman HN . Appraisal of a standardised periodontal referral proforma. Br Dent J 1999: 187: 42–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Djemal, S., Chia, M. & Ubaya-Narayange, T. Quality improvement of referrals to a department of restorative dentistry following the use of a referral proforma by referring dental practitioners. Br Dent J 197, 85–88 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811477

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811477

This article is cited by

-

Getting it right at every stage: Top tips for traumatic dental injury review: Part 1

British Dental Journal (2024)

-

Top tips for the immediate management of dental trauma

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

The development of a restorative Managed Clinical Network within the defence primary healthcare organisation

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Orthodontic retention and the role of the general dental practitioner

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Initial periodontal therapy before referring a patient: an audit

British Dental Journal (2019)