Key Points

-

Dental therapists are now permitted to work in all sectors of dentistry (from 1 July 2002).

-

The NHS Plan encourages greater use of PCDs within dentistry.

-

In general, dentists have little knowledge of the training and work practices of dental therapists.

-

Therapists are a relatively small group of PCDs – only 453 in the GDC register (December 2001).

-

Acceptance of therapists by GDPs is crucial to their employment in general dental practice.

Abstract

Objective To investigate general dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards dental therapists, to ascertain the likelihood of their employment in general dental practice, what client groups they would be likely to treat, and to identify the main perceived barriers to their employment in general dental practice.

Method Postal questionnaire.

Setting General dental practitioners in the county of West Sussex.

Sampling All dentists holding a contract to provide general dental services in West Sussex were contacted. Final sample size was 200.

Key findings Thirty eight per cent of dentists said they would employ a therapist if legislation allowed. Main perceived barriers were cost, lack of knowledge and dentists' acceptance.

Conclusions In general dentists had a favourable attitude towards dental therapists, although there was a real lack of knowledge about their permitted duties. Most dentists felt therapists should treat children and people with special needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It has been predicted that the practice of dentistry could and should become more team based1,2 and a skill mix in the future provision of dental care has been recommended.3 Dentists are, in general, aware that teamwork is important and they value the support staff that they already have4 with the majority of dentists who have qualified since the 1970s favouring a team approach.5 Previous research5,6 has found that most dentists say they are in favour of dental therapists working in general practice, with around 40% willing to employ them if legislation allowed. Barriers identified previously to the employment of therapists in practice included lack of numbers in training and levels of supervision required.6 The client groups deemed most suitable for treatment by a therapist were children and people with special needs.6 It has been suggested that dentists may wish to delegate the restoration of the primary dentition to therapists, as it can be time consuming and demanding.7 However, for therapists to be effective and efficient members of the dental team, the dentist must delegate a range of appropriate tasks to them.8,9,10 Furthermore it has been shown that patients' acceptance of therapists follows dentists' acceptance.11 Several studies have shown that the quality of work of dental therapists is at least of a similar standard to that of dentists.12,13,14,15 In general medicine, wide use is already made of professionals complementary to medicine.16 Historically therapists were permitted to work in the Community Dental Service (CDS), the Hospital Dental Service (HDS) and more recently in Personal Dental Services (PDS). In 1999 the General Dental Council recommended that therapists be allowed to work in all sectors of dentistry and this was approved from the 1st July 2002. Currently, a number of therapists are employed within PDS schemes as part of the government initiative to improve access to NHS dental care.16However, they have simply transferred from the hospital and community sectors. The aim of this study was to ascertain dentists' knowledge of and attitudes towards dental therapists in general dental practice.

Method

This study was carried out during June and July 2000. A list of dentists holding a contract to provide NHS dental care within the general dental services was obtained from West Sussex Health Authority. Following a pilot study of 20 dentists outside of West Sussex, postal questionnaires were sent to all 303 dental practitioners at their practice address. In the case of a dentist working at more than one address, the first address on the list was used. A second mailing was sent out to those dentists who failed to respond to the first mailing. The questionnaires were completed anonymously. The data were coded and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). The analysis was divided into stages: frequency distribution of each variable, relationship between variables and analysis of the open-ended question using standard qualitative methods of data analysis.

Results

Completed questionnaires were returned from 200 dentists (66%). One hundred and fifty two (76%) of the respondents were male. The mean age of the respondents was 42 (Fig. 1). Sixty-two respondents (31%) said that they had an additional qualification. Twenty-two respondents (11%) indicated that they had either MGDS or DGDP. Seven (3.5%) respondents said they had an MSc, 7 (3.5%) said they had FDS. One hundred and eighty two of the respondents (91%) were in general dental practice, with 18 (9%) stating that they worked in specialist practice, 11 (61%) of whom said they were in a practice limited to orthodontics.

When asked to indicate how busy they were, 53 (26.5%) said that they were 'too busy to treat all the people requesting appointments'. A further 58 (29%) said they could 'provide care for all who requested appointments but feel overworked'. Eighty-two of the respondents (41%), said that they could 'provide care for all who request appointments, have enough patients and do not feel overworked'. Only 7 respondents (3%) said that they were 'not busy enough, would like more patients'.

Ninety-eight (49%) were in a two or three dentist practice and 13% in single-handed practice. The largest number of dentists in a practice was eight and larger practices were more likely to employ a hygienist (p < 0.001). Figure 2 shows the distribution of respondents by practice size. Only 32 (16%) of dentists reported having had experience of working with a therapist. Just over half (54%) said they could accommodate a therapist in the practice.

Knowledge

This section of the questionnaire was designed to give an indication of the level of knowledge that dentists have regarding dental therapists. Respondents were asked to indicate a response to three statements. Table 1 shows the responses of the group. Just over half (52.5%) of the respondents indicated that they were aware of evidence that therapists can produce high quality work. Just over a third (37%) correctly indicated that therapists are not restricted to treating children. Question 3, which related to the level of supervision required, drew the least number of 'don't know' responses (24%). Less than one-fifth (17%) answered this correctly.

Attitudes

In this section respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with six statements. Table 2 summarises the responses.

'Dentists can work more effectively/efficiently using dental therapists in a team approach'

One hundred and seventeen (58.8%) expressed a favourable attitude about working with a therapist. Sixty-three (31.5%) expressed no opinion.

'In general patients don't want to be treated by dental therapists'

Almost 51% expressed no opinion. Similar proportions (25%) expressed favourable and unfavourable opinions.

'Dental therapists can make a meaningful contribution to the dental team'

Around 70% showed a favourable attitude towards the value of therapists in the dental team only 8 (4%) had an unfavourable attitude.

'Dental care will be less personalised if therapists are used for some treatment'

Forty-eight per cent disagreed with this statement and 21% expressed no opinion.

'If more use is made of therapists there won't be anything left for dentists to do'

The majority of respondents (80%) did not agree with statement, 33 (16.5%) expressed no opinion.

'Using a therapist will increase a dentist's enjoyment of dental practice'

Around 43% of the respondents showed a favourable response to therapists through delegation of tasks, a similar number (39%) were undecided.

Client groups

The respondents were asked to indicate which groups they considered were suitable for a therapist to treat. These were listed as: children, adults, children with special needs and adults with special needs. Children (91%), children with special needs (79%), adults with special needs (67%) were ranked as their preferred choices. Only 54% of dentists thought adults were a suitable client group to be treated by therapists.

If legislation allowed would you employ a therapist in general practice?

This survey found that 77 (38.5%) respondents would employ a therapist if legislation allowed, 46 (23.5%) would not employ a therapist and 77 (38.5%) were undecided. Within the group who reported that they were in a specialist practice, more than half (60%) indicated that they would employ a therapist.

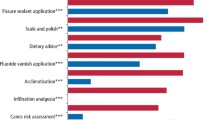

Perceived barriers

In this section of the questionnaire, respondents were asked an open-ended question 'what do you think is the biggest barrier to employing a therapist in practice?' Table 3 lists the various barriers mentioned in the responses. Some respondents mentioned more than one barrier.

The main perceived barriers to the employment of therapists in practice would appear to be financial considerations, lack of knowledge of what therapists do and dentist/patient acceptance.

With regard to financial considerations, some of the statements made included:

'lack of NHS funds . . . not sufficient to allow practices to modernise . . . let alone pay dentists adequately.'

'there is not enough money paid to us to employ a therapist on GDS.'

'if salaried, impossible to employ them for NHS.'

'the current GDS fee scale is uneconomic and employing a therapist . . . would cost me money.'

A lack of knowledge of what therapists do and how they could benefit the practice included:

'I don't know what a therapist does.'

'unknown quantity.'

'not being able to recognise medical and dental emergencies.' Although in a previous section of the questionnaire, half of the respondents had indicated that they had no opinion as to the acceptability of therapists to patients, the open–ended question drew a different response. Thirty per cent of the comments reflected a degree of concern with either dentists' or patients' acceptance of therapists. Some examples are shown below: 'patients like the continuity of seeing same dentist.'

'patients in general prefer to see the principal even if this is another GDP.'

'public will see them as a dentist.'

'I am mainly private and the patients pay to see me, not a substitute.'

'lesser skilled.'

'reluctance to change current routine, organisation required.'

'not for private practice.'

Discussion

The demographic characteristics of the study population were similar to the dentist population of the UK.19,20 The population of non-responders was identified and described in terms of age (years since qualification), gender, possession of additional qualifications. This population was similar to that of the respondents. A response rate of 66% can be considered acceptable for a survey of this type.

Knowledge

The study demonstrated a real lack of knowledge amongst dentists of what duties a therapist can carry out, the range of client groups which can be treated and the level of supervision required. This lack of knowledge was also the second most frequently mentioned barrier to employment of a therapist in practice.

Despite communications which are sent out to all dentists from the General Dental Council (GDC) regarding professionals complementary to dentistry (PCDs), there was a lack of knowledge about the level of supervision required of therapists. Less than one fifth (17%) were aware that a therapist may work outside the direct supervision of a dentist. More than half (60%) thought direct supervision was necessary and nearly a quarter did not know. However the need for supervision was not mentioned frequently as a potential barrier to employment of a therapist by the GDPs in this survey.

More than a quarter of respondents thought that dental therapists could only perform operative procedures for children. This may be as a result of knowing just a little bit of the history of therapists with regard to the New Zealand Dental Nurse and the use of therapists in the former school dental service in the UK.

Attitudes

In general, the attitudes of GDPs in West Sussex towards dental therapists were favourable; Douglass and Lipscomb11 found that teaching management skills to the supervising dentist was a prerequisite for obtaining efficiency in a practice where a therapist was employed. This survey indicates that about one in two dentists has a positive approach to team-working with a therapist, however in order for it to work well, previous research suggests that training of the dentist would be required. Jones et al.18 suggested that it is the duty of the dentist/management to create incentives and job satisfaction to encourage therapists to work at the upper limits of their abilities.

Client groups

The client groups deemed most suitable for treatment by a therapist were children and people with special needs, which corresponds generally with the findings of Hay and Batchelor.6 However in Hay and Batchelor's study,6 only 21% of GDPs felt that therapists should treat adults. There appears to be a shift in attitude with 54% of GDPs in this survey in favour of therapists treating adults. The UK Adult Dental Health Survey17 identified a change in the pattern of dental disease and the emphasis of treatment in younger adults – fewer restorations and simple minimal techniques may be more appropriate, whereas in older adults restorations may be larger and more complex, requiring advanced skills to maintain them. The authors suggest that a greater role for PCDs may help manage this change in treatment need. More than half of the specialist practices were orthodontic practices and they were most strongly in favour of employing a therapist.

Barriers

Hay and Batchelor6 found that 47.5% of GDPs would like to see therapists working in general practice, with 40% willing to employ them if legislation allowed. They found that 20% of respondents would object to other dentists employing a therapist in practice. This survey found that 39% of GDPs would employ a therapist if legislation allowed. Only 4% of respondents indicated by their responses that they were opposed to the employment of therapists in practice. Those who said they would not employ a therapist in practice did not necessarily hold a negative attitude towards therapists but were unable to consider employment due to factors such as accommodation or cost.

In previous studies,6 lack of numbers in training and lack of supervision were seen as main barriers to employment of therapists. In this study, finance, knowledge and patient acceptance were found to be the main barriers. This is interesting from the workforce point of view with the pending changes in legislation. The number of therapists in training has increased since the study by Hay and Batchelor6 with the establishment of training centres in Cardiff, Sheffield and the Eastman Dental Hospitals.

Respondents seemed reluctant to accept that therapists would generate enough income to pay their salaries. There seems to be an assumption that therapists would be employed to treat children or special needs groups mainly, and implied in this, is the expectation that dental treatment should be free or NHS for these groups. There appeared to be an underlying assumption that the NHS fees generated by treating these people would be insufficient to cover the costs involved in employing a therapist, even for the lower salary commanded by a therapist There was a perception that therapists were not appropriate for private practice amongst some of the respondents. Other concerns were the costs of fitting out a new surgery, materials, support staff etc. Unlike general medical practice there has until recently been no support for the capital development of dental practices. However, in 2001, the Government provided £35 million for the modernisation of NHS dental practices. The introduction of 'public private partnership' through NHS LIFT should provide opportunities for the capital development of dental practices.

The NHS Plan16 identified an unmet need for NHS dentistry, acknowledged that not all people want to be registered with a dentist and aimed to make NHS dentistry available to all who require it. Dental access centres were seen as one of the means of achieving this objective. These centres are encouraged to make use of the whole dental team, especially therapists. One PDS pilot in East London is using dental therapists in an area of unmet need, lower levels of dental manpower and a population of socially deprived, mobile and ethnically diverse people. The project has an emphasis on increasing uptake of dental services and improving the oral health of children. The initial results of the evaluation of this scheme have been very encouraging in relation to the working practices and performance of the therapists. Therapist output has been comparable with that of the dentists and feedback from patients has been positive. The government considers that the proposals for therapists in practice would be a powerful boost to team working but recognises that this would be limited by how many therapists are available and how quickly the numbers in training could be increased. It is hoped that the National Workforce Review currently being carried will address this. In December 2001 there were 453 enrolled therapists registered with the GDC with around 50 currently in training each year.

There has been very little research into patient's attitudes towards therapists. Half of the respondents (55%) indicated that they did not have an opinion as to whether patients would wish to be treated by therapists. This may indicate that these dentists are reluctant to express an opinion on behalf of their patients. However patient acceptance was the third most frequently mentioned perceived barrier to employment of a therapist in practice. It has been suggested that patient acceptance follows dentists' acceptance. If this is the case then more effort should be put into increasing dentists' acceptance of therapists as they will have to 'sell' the concept of shared care. This shared care happens within general medicine already, and for patients the concern is quality of care rather than who carries out the task. It would seem that dentists are happiest with the idea of working alongside a therapist rather than giving up surgery time.

It would seem most likely that larger group practices will be best placed to employ a therapist – as already happens with dental hygienists who have been able to work in general dental practice.

Whilst this study was conducted in West Sussex, it is hoped that the findings will contribute to the national debate.

Conclusion

In general, the dentists had a favourable attitude towards dental therapists, although there was a lack of knowledge of permitted duties. Therefore education of the GDP community is to be recommended.

There appears to be a shift in attitude when compared with previous studies with more dentists in favour of therapists treating adults. Also, different barriers to employment were highlighted in this study compared with previous research.

Amongst the dentists in this survey, the main concern with the employment of therapists in general practice were issues related to finance. Patient acceptance was also identified as a possible barrier to their employment, however this follows dentists' acceptance.

With the recent change in legislation which allows therapists to be employed in all branches of dentistry, knowledge of their role and acceptance by GDPs and patients is crucial.

References

Royal Commission on the National Health Service Report London: HMSO 1979

Nuffield Foundation Inquiry into dental education London: Nuffield Foundation 1980

Nuffield Foundation Education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry London: Nuffield Foundation 1993

Woolgrove J, Boyles J . Operating dental auxiliaries in the United Kingdom – a review. Community Dent Health 1984; 1: 93–99

Woolgrove J, Harris R . Attitudes of dentists towards delegation. Br Dent J 1982; 153: 339–340

Hay IS, Batchelor PA . The future role of dental therapists in the UK: a survey of district dental officers and general dental practitioners in England and Wales. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 61–65

Ireland R . Dental therapists: their future role in the dental team. Dent Update 1997 269–

Douglass CW, Gillings DB, Moor S, Lindahl RL . Expanded duty dental assistants in solo private practice. J Am Col Dent 1976; 144: 969–984

Burman N . Attitudes to the training and utilisation of dental auxiliaries in Western Australia. Austr Dent J 1987; 32: 132–135

Stephens CD, Keith O, Witt P, Sorfleet M, Edwards G, Sandy JR . Orthodontic auxiliaries – a pilot project. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 181–187

Douglass CW, Lipscomb J . Expanded function dental auxiliaries: potential for the supply of dental services in a national dental program. J Dent Educ 1979; 43: 556–567

General Dental Council Final Report on the Experimental Scheme for the Training and Employment of Dental Auxiliaries London: General Dental Council 1966

Allred H The training and use of dental auxiliary personnel. public health in Europe, WHO Report 7 Geneva: World Health Organisation 1977

Holt R, Murray JJ . An Evaluation of the role of the New Cross dental auxiliaries and of their contribution to the Community Dental Services. Br Dent J 1980; 149: 259–262

Sisty NL, Henderson WG, Paule CL . Review of training and evaluation studies in expanded functions for dental auxiliaries. J Am Dent Assoc 1979; 98: 233–248

NHS Executive Modernising NHS Dentistry – Implementing the NHS Plan London: Department of Health 2000

Nunn J, Morris J, Pine C, Pitts NB, Bradnock G, Steele J . The condition of teeth in the UK in 1998 and implications for the future. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 639–644

Jones DE, Gibbons DE, Doughty JF . The worth of a therapist. Br Dent J 1981; 151: 127–128

Newton JT, Thorogood N, Gibbons DE . The work patterns of male and female dental practitioners in the United Kingdom. Int Dent J 2000; 50: 61–68

Newton JT, Thorogood N, Gibbons DE . A study of the career development of male and female dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 90–94

Acknowledgements

A debt of gratitude is owed to the GDPs of West Sussex who kindly provided the information presented in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallagher, J., Wright, D. General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards the employment of dental therapists in general practice. Br Dent J 194, 37–41 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4802411

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4802411

This article is cited by

-

What are the possible barriers and benefits to the use of dental therapists within the UK Military Dental Service?

BDJ Team (2022)

-

What are the possible barriers and benefits to the use of dental therapists within the UK Military Dental Service?

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

The dental therapist's role in a 'shared care' approach to optimise clinical outcomes

BDJ Team (2021)

-

The dental therapist's role in a 'shared care' approach to optimise clinical outcomes

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

A whole-team approach to optimising general dental practice teamwork: development of the Skills Optimisation Self-Evaluation Toolkit (SOSET)

British Dental Journal (2020)