Abstract

Maternal separation during early childhood results in greater sensitivity to stressors later in adult life. This is reflected as greater propensity to develop stress-related disorders in humans and animal models, including anxiety and depression. Environmental enrichment (EE) reverses some of the damaging effects of maternal separation in rodent models when provided during peripubescent life, temporally proximal to the separation. It is presently unknown if EE provided outside this critical window can still rescue separation-induced anxiety and neural plasticity. In this report we use a rat model to demonstrate that a single short episode of EE in adulthood reduced anxiety-like behaviour in maternally separated rats. We further show that maternal separation resulted in hypertrophy of dendrites and increase in spine density of basolateral amygdala neurons in adulthood, long after initial stress treatment. This is congruent with prior observations showing centrality of basolateral amygdala hypertrophy in anxiety induced by stress during adulthood. In line with the ability of the adult enrichment to rescue stress-induced anxiety, we show that enrichment renormalized stress-induced structural expansion of the amygdala neurons. These observations argue that behavioural plasticity induced by early adversity can be rescued by environmental interventions much later in life, likely mediated by ameliorating effects of enrichment on basolateral amygdala plasticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adversity in early postnatal life has a lasting negative impact on behavioural and emotional functioning of individuals.1, 2, 3 Compelling evidence suggests that rodent maternal separation (MS), now widely used to mimic early-life stress in human infants, leads to hyper-reactivity of the hypothalamic−pituitary−adrenal axis in adulthood.4, 5, 6 This is accompanied by anxious or depressive-like behaviour or cognitive deficits in some instances.7, 8, 9, 10 In addition, these effects have been suggested to be downstream of neuroplasticity alterations. In particular, early-life stress leads to reductions in hippocampal neurogenesis11, 12, 13 as well as retraction of dendrites and spine density of the hippocampus14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).17, 19, 20 A single episode of MS for 24 h at postnatal day 3 does not affect dendritic complexity in the basolateral amygdala (BLA).21 It is not known if repeated MS results in BLA structural plasticity in parallel to its observed potentiation of anxiety. This is an important gap in knowledge because dendritic and spine changes in the BLA are central to stress-induced anxiogenesis.22, 23, 24

While the effects of adversity in early life possess a degree of permanence, peripubertal environmental enrichment (EE) has been shown to reverse its effects on anxiety,25, 26 depression27, 28 and learning deficits.27, 28, 29 While reversibility of developmental adversity has been demonstrated in young animals, it is presently undetermined if EE in adulthood is able to reverse the persistent effects of early-life stress long after the event. This is an important question because, if effective, an adult intervention can provide the opportunity to loosen the health burden of the temporally distant adverse past.

In this background, we experimentally test whether MS results in BLA plasticity during adulthood, and if adult EE rescues the effects of MS on anxiety-like behaviour and BLA plasticity.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Wistar rats were procured from InVivos, Singapore. Animals were maintained and mated in Nanyang Technological University vivarium on a 12:12-h light−dark schedule (lights on at 0700 h). Sires were removed from the cage once pregnancy was confirmed. All litters were weaned on postnatal day 21 (PN21). Male pups were group-housed after weaning until 6 weeks of age, when they were assigned to a density of two animals per cage. All procedures were approved by the Nanyang Technological University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Maternal separation

On PN2, litters were randomly assigned to undergo MS, or to be reared under animal facility rearing (AFR) conditions. MS was carried out from PN2 to PN14, inclusive, and consisted of daily separation of whole litters from their dams for 3 h (0900–1200 h). First, dams were removed from the home cage and placed in a clean cage in the same room. Pups were then removed from the nest one at a time and placed together in a smaller cage and kept in a quiet, separate room on a heating pad to maintain body temperature. At the end of the separation period, pups were returned to the home cage, followed by the dam. On PN2, PN9 and PN14, the pups and dam were placed in a clean home cage. AFR litters were left undisturbed except for cage change on PN2, PN9 and PN14. From PN15 to PN21, litters remained housed with dams until weaning. A total of nine litters were used (four MS, five AFR), generating a total of 49 male pups. Body weight was measured once a week from weaning (PN21) to the end of the experiment.

Environmental enrichment

On PN56, male offspring from AFR (n=23) and MS (n=26) litters were pseudorandomly divided into two housing subgroups: EE (AFR-EE, n=11; MS-EE, n=14) or standard housing (AFR-Standard, n=12; MS-Standard, n=12). Sample size was estimated based on historical variance in the laboratory for similar experiments. Housing conditions were maintained for the rest of the experiment. EE animals were housed in groups of 2–4 in a complex highly sensory environment consisting of a large, three-level cage (72 × 51 × 110 cm3) containing a variety of cylindrical plastic pipes, nesting material, toys, hanging platforms, baskets and treats. The objects within the EE cage were rearranged and renewed every four days. Non-enriched animals were housed in pairs in individually ventilated standard laboratory cages (37 x 22 x 18 cm3).

Behavioural testing

Following 14 days of EE/standard housing, animals were subjected to the home cage emergence test at PN70, and subsequently to the elevated plus maze (PN74) to measure anxiety. All behavioural procedures commenced at approximately 1000 h, with a 30-min habituation to ambient lighting conditions (number of animals tested for behavioural experiments mentioned in the previous section). The same cohort was used for all behavioural tests in the sequence specified below. Animals stayed in the EE for 14 days preceding testing and remained so until they were killed (Supplementary Figure 1). The duration of EE before behavioural testing was guided by the ability of a similar duration of EE to rescue the behavioural effects of stress when both EE and stress were provided in adulthood.30

Home cage emergence test

In the home cage emergence test, two standard laboratory rat cages with lids removed were placed 10 cm apart, with a grid placed against one of the edges of one (home cage) leading out into the other. Rats were placed in the home cage, and latency to leave the cage was measured. Leaving the cage was operationally defined when all four paws were on the grid. If the rat did not emerge from its home cage within 10 min, the session was ended and the rat was given a maximum score of 600 s. The test was carried out in dim light conditions (3−4 lux in both cages).

Elevated plus maze

The elevated plus maze apparatus consisted of a raised plus-shape maze (60 cm from ground) with two opposite arms enclosed with walls (75 × 11 × 26 cm3) and the other two arms exposed (75 × 11 cm2). Dim light was shone directly onto each open arm (6 lux). Each rat was placed in the centre square of the maze and allowed to explore freely for 5 min. All trials were video-recorded and manually analysed to quantify the percentage open-arm time and open-arm entries, relative to the sum of open and enclosed arm exploration. As a measure of risk assessment, the number of head dips was also quantified. The experimenter analysing the record was blind to animal number and treatment.

Open-field test

Animals were placed in an open circular arena (radius=120 cm, trial duration=300 s, diffused dim lighting). Time spent in the centre of the field was quantified as the reciprocal proxy of the anxiety (centre defined as a concentric circle to the arena with 0.33 m radius). Total distance travelled during the trial was also quantified as a measure of locomotion.

Brain collection

On PN84, rats were killed by decapitation. Terminal trunk blood was collected, serum was separated and used for estimation of corticosterone concentration using a commercial EIA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, ADI-900-097, Farmingdale, NY, USA). The brain was quickly removed and processed for Golgi staining using the FD Rapid GolgiStainTM kit (FD Neurotechnologies, Columbia, SC, USA). Coronal sections (100 μm thickness) were then cut using a cryostat (Leica CM3050-S, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and collected on gelatinized slides. Sections were counterstained in 0.25% cresyl violet solution and coverslipped using Permount mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, Singapore).

Dendritic morphology of BLA neurons

A random proportion of animals from each group was used for morphological analysis (AFR-Standard: n=6; AFR-EE: n=9; MS-Standard: n=9; MS-EE: n=9). Complete stellate or pyramidal-like neurons in the BLA, consisting of the lateral and basal nuclei, were selected for tracing using a microscope (Olympus BX43, Tokyo, Japan, × 40 objective lens) with the aid of a camera lucida. For each animal, 10−11 neurons were drawn to yield a representative sample of BLA neurons for each group. Custom-designed macros embedded in ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) were used for analysis of scanned images to quantify total dendritic length and total number of branch points. All neurons were drawn and analysed by an experimenter blind to treatment. The codes were not broken until quantification for dendritic length and spine density was concluded. Dendritic length and branch points of prelimbic mPFC neurons were quantified in the same cohort of animals.

Spine density of BLA neurons

Using the same microscope (Olympus BX43, 1.3 numerical aperture, × 100 objective lens), all protrusions from dendrite, irrespective of morphological characteristics, were counted as spines. Dendrites directly originating from the cell soma were classified as primary dendrites, and the first branch emerging from the primary dendrite was classified as the secondary dendrite. Starting from the origin of the branch, and continuing away from the cell soma, spines were counted along a 60-μm stretch of the dendrite. Spine density was quantified in 6–10 neurons per animal to yield a representative sample of BLA neurons for each group.

Statistical analyses

Normality for behavioural and morphological end points was examined using the Shapiro−Wilk test. Several end points exhibited significant departure from normality (Table 1). Consequently non-parametric statistics was used for intergroup comparisons (Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance). When significant intergroup differences were indicated, group-wise post-hoc comparisons were conducted using Mann−Whitney U test (two-tailed). The AFR group was compared with the MS group, either in the presence or in the absence of EE. Resultant type 1 error probabilities were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction. Figures depict median and interquartile range. Effect size was calculated using Cliff’s delta, a non-parametric statistic.31 All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics 21 (Armonk, NY, USA) or GraphPad Prism 6 software (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

There were no significant differences in litters randomly chosen to undergo MS and AFR, in terms of both litter size (Student’s t-test; t(7) =1.49, P=0.18) and number of male pups (t(7) =1.76, P=0.12). At weaning (PN21), male pups exposed to MS weighed significantly less compared to the AFR group (AFR: 45.50±0.7 g; MS: 42.60±1.1 g; t(47)=2.20, P=0.03). MS-treated animals continued to weigh less than non-MS animals into the adulthood (Supplementary Figure 2). Several behavioural and structural end points exhibited non-normal frequency distribution (Table 1). A rank transformation of data failed to institute normality. In view of non-normal distribution, all subsequent data analysis employed non-parametric alternatives.

Home cage emergence test

Latency to emerge from home cage was quantified as a reciprocal end point for anxiety-like behaviour (Figure 1). Kruskal−Wallis test revealed significant intergroup differences (χ2=25.3, df=3, P=0.0001). Subsequent post-hoc analysis revealed significantly higher emergence latency in MS rats compared to AFR when both groups were housed in standard conditions during adulthood (Figure 1; Mann−Whitney U test: |z|=2.40, P=0.032 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons; n=12 for AFR-Standard and MS-Standard). The 25th percentile of MS-Standard animals was observed to be greater than the 75th percentile of the AFR-Standard group, suggesting a robust increase in emergence latency due to MS (effect size in Table 1). In contrast, MS did not significantly increase emergence latency in the presence of EE (Figure 1 and Table 1; |z|=0.27, P=0.784 before Bonferroni correction; n=11 for AFR-EE and 14 for MS-EE).

Effect of maternal separation (MS) and environmental enrichment (EE) on latency to emerge from the home cage. The figure depicts the median and interquartile range (between 25th to 75th percentiles) of emergence latency. *P<0.01 for comparison between MS and animal facility rearing (AFR) groups; Mann−Whitney U test, Bonferroni correction applied for multiple (X2) comparisons. N=12 animals for AFR-Standard, 12 for MS-Standard, 11 for AFR-EE and 14 for MS-EE.

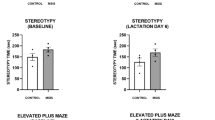

Elevated plus maze

The elevated plus maze was used as a second assessment for anxiety-like behaviour, with decreased open-arm entries and time indicative of heightened anxiety. Kruskal−Wallis test revealed significant intergroup differences for percentage open-arm entries (relative to sum of open and enclosed arms, %; X2=15.7, df=3, P=0.0013) and percentage open-arm time (X2=24.7, df=3, P=0.0002). Congruent to emergence latency from home cage, MS caused robust decrease in percentage open-arm entries when housed in standard conditions during adulthood (Figure 2a; |z|=3.00, P=0.006 after Bonferroni correction). In contrast, differences between MS and AFR groups were not statistically significant when animals were housed in enriched environment (|z|=1.07, P=0.57 after Bonferroni correction). Similarly, MS significantly decreased percentage open-arm time in the absence of EE (Figure 2b; |z|=3.65, P=0.001 after Bonferroni correction), but not in the presence of EE (|z|=0.06, P=0.956 before Bonferroni correction).

Effect of maternal separation (MS) and environmental enrichment (EE) on percentage open-arm entries (a), percentage open time (b), number of head dips (c) in elevated plus maze and time spent in the centre of an open-field arena (d). Percentage open-arm exploration is quantified relative to the sum of open- and enclosed-arm exploration, in %. *P<0.01 for comparison between MS and animal facility rearing (AFR) groups; Mann−Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. N is similar to Figure 1. N=14 animals for AFR-Standard, 10 for MS-Standard, 15 for AFR-EE and 10 for MS-EE for D.

In addition to quantifying entries in open and enclosed arms, we also measured the number of head dips as a measure of risk assessment (Figure 2c). Kruskal−Wallis test revealed significant intergroup differences for this end point (X2=28.6, df=3, P<0.0001). MS treatment resulted in a significant decrease in risk assessment under standard housing conditions (Figure 2c; |z|=3.61, P=0.001 after Bonferroni correction). The effect of MS on head dips was absent when animals were housed under EE (|z|=0.80, P=0.850 after Bonferroni correction).

Estimates of effect size (Table 1) demonstrated a robust effect of MS on all parameters during elevated plus maze paradigms. Thus, the effect size for anxiety parameters exceeded a relatively robust level of 0.65 after exposure to MS. This is also borne out by the observations that, in all parameters, the 75th percentile of MS animals was lower than the 25th percentile of the AFR group (Figure 2). Adult provision to EE substantially diminished the effect sizes for MS exposure (Cliff’s delta between −0.25 to 0.25; Table 1).

Open-field test

Time spent in the centre of the open-field arena and total locomotion in the arena were quantified. Kruskal−Wallis test revealed significant intergroup differences for occupancy in the centre (Figure 2d; X2=22.8, df=3, P<0.0001). Subsequent post-hoc analysis did not reveal statistically significant effect of MS on time spent in the centre, in either absence (P>0.2) or presence (P>0.7) of EE. In the non-MS group of animals, EE significantly increased time spent in the centre of the arena (P<0.001 after Bonferroni correction). Distance travelled in the open field did not show significant intergroup differences (X2=0.98, df=3, P>0.8), suggesting comparable locomotion between experimental groups.

Dendritic morphology of BLA neurons

Two parameters, total dendritic length and number of branch points, were quantified in 334 BLA neurons (8−11 neurons per animal, average for each individual animal used for statistical analysis). Kruskal−Wallis test revealed significant intergroup differences for both total dendritic length (μm; X2=8.5, df=3, P=0.037) and total number of branch points (X2=19.1, df=3, P<0.003).

MS resulted in a significant hypertrophy of BLA neurons. This was evident as increase in both total dendritic length (Figure 3a; |z|=2.47, P=0.026 after Bonferroni correction) and number of branch points (Figure 3b; |z|=2.95, P=0.006 after Bonferroni correction). MS-induced hypertrophy did not reach statistical significance when animals were provided with EE (|z|=0.22, P=0.863 before Bonferroni correction for both dendritic length and branch points). In the absence of EE, the 25th percentile of MS animals was greater than the 75th percentile of the AFR group (Figures 3a and b), resulting in a robust effect size of >0.75 (Table 1). This increase in dendritic parameters was normalized in the presence of EE (effect size=0.06).

Effect of maternal separation (MS) and environmental enrichment (EE) on total dendritic length (a, μm) and number of branch points (b) of principal basolateral amygdala neurons. *P<0.01 for comparison between MS and animal facility rearing (AFR) groups; Mann−Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. N=6 animals for AFR-Standard, 9 animals for all other groups; the value for each individual animal was derived as the average of 8–11 unique neurons.

Figure 4 depicts camera lucida traces of representative neurons.

Dendritic length and branch points of prelimbic mPFC neurons were quantified in the same cohort of animals (8 neurons per animal, average for each individual animal used for statistical analysis; Table 1). Kruskal−Wallis test did not reveal significant intergroup differences for both total dendritic length (Supplementary Figure 3; μm; X2=1.74, df=3, P=0.627) and total number of branch points (X2=1.39, df=3, P=0.708).

Spine density of BLA neurons

The number of spines was quantified in a 60-μm segment of primary and secondary dendrites (Figure 5). Kruskal−Wallis test revealed significant intergroup differences for both primary (number of spines per 60 μm; X2=7.7, df=3, P=0.05) and secondary dendrites (X2=13.5, df=3, P<0.004). In cases of both primary and secondary dendrites, post-hoc analysis indicated significant increase in spine density due to MS exposure (Figures 5a and b; |z|>2.32, P<0.04 after Bonferroni correction). The MS-induced increase in spine density was renormalized when animals were exposed to EE during adulthood (|z|<0.85, P>0.40 before Bonferroni correction). Consistent with dendritic parameters, the 25th percentile of MS-Standard animals exceeded the 75th percentile of the AFR-Standard group, suggesting a robust experimental effect (Table 1; effect size>0.75). In contrast, exposure to EE reduced the effect sizes for MS treatment.

Effect of maternal separation (MS) and environmental enrichment (EE) on the spine density in primary (a, per 60 μm) and secondary (b) dendrites of principal BLA neurons. *P<0.01 for comparison between MS and animal facility rearing (AFR) groups; Mann−Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. N=6 animals for AFR-Standard, 8 animals for all other groups; the value for each individual animal was derived as the average of 8–11 unique neurons.

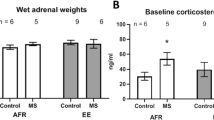

Serum corticosterone concentration

Serum concentration of stress hormone corticosterone was quantified in trunk blood obtained during death. Corticosterone concentration did not show significant intergroup differences (X2=0.80, df=3, P>0.8). This suggests that stress hormones circulating at the baseline in adulthood were not different between experimental groups (Supplementary Figure 4).

Discussion

The data presented in this report demonstrate that MS in early life leads to structural changes in the BLA during adulthood. BLA is a critical brain region in the generation and maintenance of conditioned fear and generalized anxiety (succinctly reviewed in Fanselow and LeDoux,32 Pare,33 Nathan et al.34 and Boyle35). For example, traumatic stress in the form of predator exposure in adult rats causes long-lasting anxiety. This anxiogenesis is dependent on the BLA36 and secretion of stress hormones.37, 38 Similarly, lesions of the BLA rescue the effects of stress hormones on a variety of memory processes.39, 40, 41, 42

Prior work has shown that chronic stress or exogenous glucocorticoids during adulthood precipitate dendritic hypertrophy of the BLA projection neurons.23, 24 Stress also enhances spine density 22 and reduces synaptic inhibition on these neurons.43 These observations suggest that stress or stress hormones act within the BLA, causing structural expansion and increased excitability. Such stress-induced facilitation consequently leads to greater anxiety, given the pivotal role of the BLA in the generalized fear. This suggestion is buttressed by the observation that augmentation of BLA dendrites co-occurs with more anxiety;22, 23, 44 blockade of stress hormonal action in or experimental reduction of dendritic length within the BLA reduces anxiety;45, 46 and inter-individual variation in stress-induced anxiety co-elutes with the dendritic architecture of BLA neurons.47 In light of these observations, we suggest that structural changes in BLA projection neurons long after MS results in the increased anxiety reported here and elsewhere.

Previous studies have reported effects of MS on the dendritic architecture of PFC projection neurons.17, 20 Adolescent and postpubertal rats exhibit reduced dendritic complexity and lower spine density in these neurons after MS. Similarly, MS suppresses dendritic complexity of neurons in the hippocampus and nucleus accumbens. These observations are in marked contrast to dendritic expansion and denser spines reported in the present study. Interestingly, chronic stress during adulthood also results in contrasting changes in the BLA vis-à-vis the hippocampus or the PFC.22, 23, 24, 48, 49, 50 Congruently, MS causes contrasting changes in the behaviours mediated by these structures. For example, MS results in deficits of hippocampus dependent spatial memory and PFC dependent extinction recall of conditioned fear.16, 51 In contrast, MS increases anxiety-like behaviour consistent with the role of the BLA in anxiety. We posit that the differential effects of MS on BLA dendrites, compared to hippocampal and prefrontal neurons, underlie the disparate effects of early-life stress on anxiety and memory processes. Furthermore, a single acute session of MS does not result in the dendritic changes in BLA.21 Thus, the chronic and repetitive aspects of MS employed here are likely necessary for the BLA's structural plasticity.

EE is reported to have positive effects on a variety of emotional and cognitive parameters (reviewed in Alwis and Rajan,52 Arai and Feig,53 Eckert and Abraham,54 Hannan,55 Pang and Hannan,56 and van Praag et al.57). In case of MS effects, peripubertal EE immediately after weaning rescues the effects of MS on endocrine reactivity to acute stress.25 Thus, MS increases stress-induced release of corticosterone from adrenal glands and enhances the amount of corticotrophin-releasing factor present in the hypothalamus, suggesting greater sensitivity to acute stress during adulthood. Fifty-days-long peripubertal EE starting at PN21 renormalizes such stress reactivity, in parallel to also rescuing MS-induced anxiety in an open-field test. Similarly, peripubertal EE also rescues the cognitive effects of low maternal care in rats.29 In contrast to these reports, the present observations suggest that a relatively short EE spanning 2 weeks and starting much later in adult life is sufficient to rescue both behavioural consequences of MS and underlying neuronal changes. Thus, the presence of a long environmental intervention during adolescence is sufficient, but not necessary, for the rescue. Similar renormalization can also be achieved outside the critical peripubertal window and through a shorter intervention.

The current data suggest that circuits underlying emotional behaviour maintain a degree of plasticity in adulthood, such that positive and stimulating environments can overcome the effects of adversity applied during a highly sensitive period of brain development. In addition, our findings propose neuroplasticity in the amygdala as a likely candidate in mediating the reversal of MS effects. Altered neuronal morphology could therefore be a phenotype for increased risk of affective behaviour following early-life stress, and may provide a potential target for treatment of mental disorders associated with early adversity. At the same time, our findings also propose environmental stimulation in adulthood as a possible therapy for neuropsychiatric conditions associated with early-life stress, particularly those known to involve altered amygdala structure and function.

References

Heim C, Nemeroff CB . The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 49: 1023–1039.

Taylor SE, Way BM, Seeman TE . Early adversity and adult health outcomes. Dev Psychopathol 2011; 23: 939–954.

Sanchez MM, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM . Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: evidence from rodent and primate models. Dev Psychopathol 2001; 13: 419–449.

Ladd CO, Huot RL, Thrivikraman KV, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM . Long-term adaptations in glucocorticoid receptor and mineralocorticoid receptor mRNA and negative feedback on the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis following neonatal maternal separation. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55: 367–375.

Ladd CO, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB . Persistent changes in corticotropin-releasing factor neuronal systems induced by maternal deprivation. Endocrinology 1996; 137: 1212–1218.

Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ . Early, postnatal experience alters hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) mRNA, median eminence CRF content and stress-induced release in adult rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1993; 18: 195–200.

Ladd CO, Huot RL, Thrivikraman KV, Nemeroff CB, Meaney MJ, Plotsky PM . Long-term behavioral and neuroendocrine adaptations to adverse early experience. Prog Brain Res 2000; 122: 81–103.

Huot RL, Plotsky PM, Lenox RH, McNamara RK . Neonatal maternal separation reduces hippocampal mossy fiber density in adult Long Evans rats. Brain Res 2002; 950: 52–63.

Aisa B, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Del Rio J, Ramirez MJ . Effects of maternal separation on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses, cognition and vulnerability to stress in adult female rats. Neuroscience 2008; 154: 1218–1226.

Lajud N, Roque A, Cajero M, Gutierrez-Ospina G, Torner L . Periodic maternal separation decreases hippocampal neurogenesis without affecting basal corticosterone during the stress hyporesponsive period, but alters HPA axis and coping behavior in adulthood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012; 37: 410–420.

Mirescu C, Peters JD, Gould E . Early life experience alters response of adult neurogenesis to stress. Nat Neurosci 2004; 7: 841–846.

Hulshof HJ, Novati A, Sgoifo A, Luiten PG, den Boer JA, Meerlo P . Maternal separation decreases adult hippocampal cell proliferation and impairs cognitive performance but has little effect on stress sensitivity and anxiety in adult Wistar rats. Behav Brain Res 2011; 216: 552–560.

Aisa B, Elizalde N, Tordera R, Lasheras B, Del Rio J, Ramirez MJ . Effects of neonatal stress on markers of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus: implications for spatial memory. Hippocampus 2009; 19: 1222–1231.

Brunson KL, Kramar E, Lin B, Chen Y, Colgin LL, Yanagihara TK et al. Mechanisms of late-onset cognitive decline after early-life stress. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 9328–9338.

Ivy AS, Rex CS, Chen Y, Dube C, Maras PM, Grigoriadis DE et al. Hippocampal dysfunction and cognitive impairments provoked by chronic early-life stress involve excessive activation of CRH receptors. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 13005–13015.

Oomen CA, Soeters H, Audureau N, Vermunt L, van Hasselt FN, Manders EM et al. Severe early life stress hampers spatial learning and neurogenesis, but improves hippocampal synaptic plasticity and emotional learning under high-stress conditions in adulthood. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 6635–6645.

Monroy E, Hernandez-Torres E, Flores G . Maternal separation disrupts dendritic morphology of neurons in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens in male rat offspring. J Chem Neuroanat 2010; 40: 93–101.

Champagne DL, Bagot RC, van Hasselt F, Ramakers G, Meaney MJ, de Kloet ER et al. Maternal care and hippocampal plasticity: evidence for experience-dependent structural plasticity, altered synaptic functioning, and differential responsiveness to glucocorticoids and stress. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 6037–6045.

Bock J, Gruss M, Becker S, Braun K . Experience-induced changes of dendritic spine densities in the prefrontal and sensory cortex: correlation with developmental time windows. Cereb Cortex 2005; 15: 802–808.

Chocyk A, Bobula B, Dudys D, Przyborowska A, Majcher-Maslanka I, Hess G et al. Early-life stress affects the structural and functional plasticity of the medial prefrontal cortex in adolescent rats. Eur J Neurosci 2013; 38: 2089–2107.

Krugers HJ, Oomen CA, Gumbs M, Li M, Velzing EH, Joels M et al. Maternal deprivation and dendritic complexity in the basolateral amygdala. Neuropharmacology 2012; 62: 534–537.

Mitra R, Jadhav S, McEwen BS, Vyas A, Chattarji S . Stress duration modulates the spatiotemporal patterns of spine formation in the basolateral amygdala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 9371–9376.

Mitra R, Sapolsky RM . Acute corticosterone treatment is sufficient to induce anxiety and amygdaloid dendritic hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 5573–5578.

Vyas A, Mitra R, Shankaranarayana Rao BS, Chattarji S . Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling in hippocampal and amygdaloid neurons. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 6810–6818.

Francis DD, Diorio J, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ . Environmental enrichment reverses the effects of maternal separation on stress reactivity. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 7840–7843.

Ilin Y, Richter-Levin G . Enriched environment experience overcomes learning deficits and depressive-like behavior induced by juvenile stress. PLoS One 2009; 4: e4329.

Cui M, Yang Y, Yang J, Zhang J, Han H, Ma W et al. Enriched environment experience overcomes the memory deficits and depressive-like behavior induced by early life stress. Neurosci Lett 2006; 404: 208–212.

Hui JJ, Zhang ZJ, Liu SS, Xi GJ, Zhang XR, Teng GJ et al. Hippocampal neurochemistry is involved in the behavioural effects of neonatal maternal separation and their reversal by post-weaning environmental enrichment: a magnetic resonance study. Behav Brain Res 2011; 217: 122–127.

Bredy TW, Humpartzoomian RA, Cain DP, Meaney MJ . Partial reversal of the effect of maternal care on cognitive function through environmental enrichment. Neuroscience 2003; 118: 571–576.

Mitra R, Sapolsky RM . Effects of enrichment predominate over those of chronic stress on fear-related behavior in male rats. Stress 2009; 12: 305–312.

Macbeth G, Razumiejczyk E, Ledesma RD . Cliff's Delta Calculator: a non-parametric effect size program for two groups of observations. Univ Psychol 2011; 10: 545–555.

Fanselow MS, LeDoux JE . Why we think plasticity underlying Pavlovian fear conditioning occurs in the basolateral amygdala. Neuron 1999; 23: 229–232.

Pare D . Role of the basolateral amygdala in memory consolidation. Prog Neurobiol 2003; 70: 409–420.

Nathan SV, Griffith QK, McReynolds JR, Hahn EL, Roozendaal B . Basolateral amygdala interacts with other brain regions in regulating glucocorticoid effects on different memory functions. Ann NY Acad Sci 2004; 1032: 179–182.

Boyle LM . A neuroplasticity hypothesis of chronic stress in the basolateral amygdala. Yale J Biol Med 2013; 86: 117–125.

Adamec RE, Burton P, Shallow T, Budgell J . Unilateral block of NMDA receptors in the amygdala prevents predator stress-induced lasting increases in anxiety-like behavior and unconditioned startle—effective hemisphere depends on the behavior. Physiol Behav 1999; 65: 739–751.

Adamec RE, Blundell J, Burton P . Relationship of the predatory attack experience to neural plasticity, pCREB expression and neuroendocrine response. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2006; 30: 356–375.

Adamec R, Muir C, Grimes M, Pearcey K . Involvement of noradrenergic and corticoid receptors in the consolidation of the lasting anxiogenic effects of predator stress. Behav Brain Res 2007; 179: 192–207.

Quirarte GL, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL . Glucocorticoid enhancement of memory storage involves noradrenergic activation in the basolateral amygdala. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94: 14048–14053.

Roozendaal B, McReynolds JR, Van der Zee EA, Lee S, McGaugh JL, McIntyre CK . Glucocorticoid effects on memory consolidation depend on functional interactions between the medial prefrontal cortex and basolateral amygdala. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 14299–14308.

Moriceau S, Wilson DA, Levine S, Sullivan RM . Dual circuitry for odor-shock conditioning during infancy: corticosterone switches between fear and attraction via amygdala. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 6737–6748.

Debiec J, Sullivan RM . Intergenerational transmission of emotional trauma through amygdala-dependent mother-to-infant transfer of specific fear. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 12222–12227.

Rainnie DG, Bergeron R, Sajdyk TJ, Patil M, Gehlert DR, Shekhar A . Corticotrophin releasing factor-induced synaptic plasticity in the amygdala translates stress into emotional disorders. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 3471–3479.

Vyas A, Chattarji S . Modulation of different states of anxiety-like behavior by chronic stress. Behav Neurosci 2004; 118: 1450–1454.

Mitra R, Ferguson D, Sapolsky RM . SK2 potassium channel overexpression in basolateral amygdala reduces anxiety, stress-induced corticosterone secretion and dendritic arborization. Mol Psychiatry 2009; 14: 847–855, 27.

Mitra R, Sapolsky RM . Expression of chimeric estrogen-glucocorticoid-receptor in the amygdala reduces anxiety. Brain Res 2010; 1342: 33–38.

Mitra R, Adamec R, Sapolsky R . Resilience against predator stress and dendritic morphology of amygdala neurons. Behav Brain Res 2009; 205: 535–543.

Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Miller M, Janssen WG, Liston C, Hof PR et al. Repeated stress induces dendritic spine loss in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex 2006; 16: 313–320.

Radley JJ, Sisti HM, Hao J, Rocher AB, McCall T, Hof PR et al. Chronic behavioral stress induces apical dendritic reorganization in pyramidal neurons of the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 2004; 125: 1–6.

Wellman CL . Dendritic reorganization in pyramidal neurons in medial prefrontal cortex after chronic corticosterone administration. J Neurobiol 2001; 49: 245–253.

Xiong GJ, Yang Y, Wang LP, Xu L, Mao RR . Maternal separation exaggerates spontaneous recovery of extinguished contextual fear in adult female rats. Behav Brain Res 2014; 269: 75–80.

Alwis DS, Rajan R . Environmental enrichment and the sensory brain: the role of enrichment in remediating brain injury. Front Systems Neurosci 2014; 8: 156.

Arai JA, Feig LA . Long-lasting and transgenerational effects of an environmental enrichment on memory formation. Brain Res Bull 2011; 85: 30–35.

Eckert MJ, Abraham WC . Effects of environmental enrichment exposure on synaptic transmission and plasticity in the hippocampus. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2013; 15: 165–187.

Hannan AJ . Environmental enrichment and brain repair: harnessing the therapeutic effects of cognitive stimulation and physical activity to enhance experience-dependent plasticity. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014; 40: 13–25.

Pang TY, Hannan AJ . Enhancement of cognitive function in models of brain disease through environmental enrichment and physical activity. Neuropharmacology 2013; 64: 515–528.

van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH . Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nat Rev Neurosci 2000; 1: 191–198.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Nanyang Technological University (M4081146), Singapore. The authors thank Ng Yan Ling for assistance with data collection and Dr Ajai Vyas for assistance with editing the final script.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Koe, A., Ashokan, A. & Mitra, R. Short environmental enrichment in adulthood reverses anxiety and basolateral amygdala hypertrophy induced by maternal separation. Transl Psychiatry 6, e729 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.217

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.217

This article is cited by

-

Early-life stress biases responding to negative feedback and increases amygdala volume and vulnerability to later-life stress

Translational Psychiatry (2023)

-

Maternal separation and its developmental consequences on anxiety and parvalbumin interneurons in the amygdala

Journal of Neural Transmission (2023)

-

Environmental Enrichment Rescues Oxidative Stress and Behavioral Impairments Induced by Maternal Care Deprivation: Sex- and Developmental-Dependent Differences

Molecular Neurobiology (2023)

-

Environmental enrichment rescues survival and function of adult-born neurons following early life stress

Molecular Psychiatry (2021)

-

Enriched Environment Minimizes Anxiety/Depressive-Like Behavior in Rats Exposed to Immobilization Stress and Augments Hippocampal Neurogenesis (In Vitro)

Journal of Molecular Neuroscience (2021)