Abstract

Perceiving others in pain generally leads to empathic concern, consisting of both emotional and cognitive processes. Empathy deficits have been considered as an element contributing to social difficulties in individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Here, we used functional magnetic resonance imaging and short video clips of facial expressions of people experiencing pain to examine the neural substrates underlying the spontaneous empathic response to pain in autism. Thirty-eight adolescents and adults of normal intelligence diagnosed with ASD and 35 matched controls participated in the study. In contrast to general assumptions, we found no significant differences in brain activation between ASD individuals and controls during the perception of pain experienced by others. Both groups showed similar levels of activation in areas associated with pain sharing, evidencing the presence of emotional empathy and emotional contagion in participants with autism as well as in controls. Differences between groups could be observed at a more liberal statistical threshold, and revealed increased activations in areas involved in cognitive reappraisal in ASD participants compared with controls. Scores of emotional empathy were positively correlated with brain activation in areas involved in embodiment of pain in ASD group only. Our findings show that simulation mechanisms involved in emotional empathy are preserved in high-functioning individuals with autism, and suggest that increased reappraisal may have a role in their apparent lack of caring behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have impaired social understanding, and seemingly reduced reactions to others’ emotions, which may be interpreted as lack of empathetic concern. Empathy can be defined as ‘the ability to form an embodied representation of another’s emotional state, while at the same time being aware of the causal mechanism that induced the emotional state in the other'.1 Empathy is a multicomponent process, consisting mainly of experience sharing and mental state attribution.2 The evolutionary precursor of empathy is emotional contagion, a phylogenetically old phenomenon, even observable in distressed mice.3 Emotional contagion is a precursor of emotional empathy,4 whereby embodiment entails the forming of a representation of the other person’s feelings, and thereby sharing of their experience.5 In the observer, this ‘perception-action’ coupling mechanism elicits the activation of the same neural networks as in the person experiencing the emotional state.6

When facing others’ pain, empathy-related behaviors are commonly elicited. Defined as an emotional and unpleasant experience related to genuine or potential bodily damage,7 the experience of pain instigates the activation of a large network of brain areas, also referred to as the pain matrix, including the anterior insula (AI), somato-sensory cortices (SI, SII), supplementary motor area (SMA), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), periaqueductal gray, thalamus and cerebellum (reviewed in Peyron et al.8 and Decety9). Functional neuroimaging studies have repeatedly demonstrated activation of the pain matrix during the perception of vicarious pain,10, 11, 12, 13 and this activation is stronger in those with high empathy scores.10,14, 15, 16

In parallel to emotional contagion, the perception of others’ affective states induces emotional arousal, leading to activation in the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus and orbito-frontal cortex (OFC) (for example, see Decety9). These two processes, emotional contagion and emotional arousal, key elements of emotional empathy, have a central role in empathic experiences.

In contrast to emotional empathy, cognitive empathy is akin to emotion understanding and requires perspective taking and mentalizing; it can also be understood as theory of mind (ToM). Consistently activated in mentalizing tasks,17 the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) drives perspective taking during the perception of facial expressions of pain.16,18 Impairments in ToM have been described in ASD (reviewed in Senju19) and likely overlap with deficits in the expression of cognitive empathy.

Impairments in cognitive empathy, but presence of normal empathetic concern (emotional empathy), have indeed been reported in adults with Asperger syndrome (AS), based on self-report questionnaires such as the Interpersonal Reactivity Index20 and the Multifaceted Empathy Test.21 This specific empathy profile observed in adults has also been described in children and adolescents with ASD.22 In contrast, measures of personal distress, one of the emotional subscales of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, is higher in individuals with AS compared with controls.20 Individuals with ASD have therefore been hypothesized to have a hypersensitive aspect of the emotional reactions to suffering in others, possibly leading to emotional distress, in the absence of normal cognitive empathy.23,24 Support for this theory has recently been provided by a study where individuals with ASD were shown to exhibit heightened empathic arousal when perceiving others' distress. 25

The underpinnings of empathy for pain have mostly been investigated using cues indicating the suffering of someone close or a partner, or using pictures showing limbs (hand or foot) in painful situations (reviewed in Singer26). In real-life situations, however, expressions conveyed by faces have a key role in the perception of others’ emotional experience. Neural correlates of the capacity to empathize with facial expressions of other’s pain have been assessed only in a few studies and have demonstrated engagement of brain areas involved in the first person experience of pain.12,15,16,18,27,28

Cognitive reappraisal is a mechanism allowing to regulate emotions through the reinterpretation of the meaning of an emotional stimulus. This regulation is crucial for the discrimination between self- and other-related states and engages prefrontal regions and the ACC. Via reappraisal mechanisms, these brain regions can downregulate amygdala activity (reviewed for example in Decety9). Mental state attribution and perspective taking are key processes ensuring the experience of empathic concern rather than personal distress.

In this study, we focused on the implicit processing of facial expressions of other’s pain in ASD. We investigated whether the neural substrates of emotional and cognitive components of empathy are atypically activated in high-functioning participants with ASD when viewing dynamic facial expressions of real pain.

Materials and methods

Participants

The Lausanne University Hospital ethics committee approved all procedures. All adult participants gave written informed consent before the start of the study. Minor participants provided assent and one of their parents gave written consent. All procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki. Seventy-two individuals were enrolled in the experiment: 38 subjects with ASD from three centers (Lausanne, Brest and Gothenburg) and 35 control subjects (CON) who were recruited in Lausanne and had no history of psychiatric or neurological disorders. All subjects were scanned in Lausanne. Six subjects were excluded from the data analysis because of excessive movement or for not performing the task during the scan (2 ASD and 4 CON). Thus, 36 participants with ASD (3 women, 23.5±8.7 years (mean age±s.d.), range 13–44) and 31 CON (3 women, 22.5±7.5 years, range 13–43) were included in the final analysis. Participants’ characteristics are given in Table 1.

Participants with ASD were diagnosed by experienced clinicians according to DSM IV-TR criteria.29 In addition, the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised30 was conducted in 26 participants and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule31 in 28 individuals. Eight participants were assessed using the Diagnosis of Social and Communication Disorder-10.32 All 36 participants met cutoff criteria for a diagnosis of ASD—24 for Asperger syndrome, 10 for autistic disorder and 2 for pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified.

Performance Intelligence Quotient was assessed using the Wechsler Nonverbal Scale of Ability33 or the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence34 and all participants had a performance Intelligence Quotient in the normal range. ASD and CON groups did not differ for age and for performance Intelligence Quotient (P>0.05). All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

Autistic traits were evaluated in all participants using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) self-report questionnaire.35,36 This questionnaire consists of 50 items assessing five domains known to be affected in ASD, namely, social skills, communication skills, imagination, attention to detail and attention switching/tolerance of change. It is continuously distributed in the general population, ranges between 0 and 50 and it has been shown that a cutoff of 26 results in a sensitivity of 0.95, specificity of 0.52, positive predictive value of 0.84 and negative predictive value of 0.78.37

The level of empathy was assessed with the Empathy Quotient (EQ) questionnaire.38 The EQ is a 60-item (40 empathy items and 20 fillers) self-report questionnaire, ranging between 0 and 120. Principal component analysis of the EQ has revealed the following three factors: cognitive empathy, social skills and emotional reactivity—we henceforth refer to these three factors as cognitive EQ, social EQ and emotional EQ, respectively.39,40 ‘Cognitive EQ’ measures the appreciation of the affective states of others and can be understood as a test of perspective taking/ToM. ‘Social EQ’ tests for the intuitive understanding of social situations and the spontaneous use of such skills. ‘Emotional EQ’ reflects the tendency to have an emotional reaction in response to other people’s mental states, and has been shown to be related to anxiety.40

Visual stimuli and design

Two-second movies of facial expressions of adult patients from a shoulder clinic were presented. Videos showed 21 different faces (11 men) filmed during movement either of their painful (PAIN condition) or their healthy shoulder (NO PAIN condition) (see Botvinick et al.12 and Lawrence et al.41 for details). The videos, which showed frontal views of patients’ facial expressions, were scored using a validated index of facial pain expression41 based on the facial action coding system.42 Pain expressions were all related to pain according to facial action coding system, whereas control expressions contained no facial action correlated with pain. Video clips displaying painful expressions were edited such that the last image frame shown was the one with the strongest pain expression. Movies were presented in 12 blocks (6 PAIN and 6 NO PAIN), in pseudo-random order. Each block consisted of four different video clips, each followed by a 1-s black screen. Between blocks, a central red fixation cross was shown for 6 s. Four times during each run, a blue cross was presented for 1 s. As we wanted to evaluate implicit empathic reactivity, we did not ask participants to feel what the person on the video was experiencing, nor to rate the level of pain experienced. Participants were instructed to carefully look at the videos and, in order to monitor their attention, to press a button every time the blue cross appeared. Two runs were presented.

Imaging data acquisition and analysis

Anatomical and functional magnetic resonance images were collected in all participants with a 12-channel radio frequency coil in a Siemens 3T scanner (Siemens Tim Trio, Erlangen, Germany) at the Centre d’Imagerie BioMédicale in Lausanne. The first scanning sequence consisted of Siemens’s autoalign scout for the head allowing an automatic positioning and alignment of slices. Anatomical images were acquired using a multi-echo magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequence: 176 slices; 256 × 256 matrix; echo time (TE): TE1: 1.64 ms, TE2: 3.5 ms, TE3: 5.36 ms, TE4: 7.22 ms; repetition time (TR): 2530 ms; flip angle 7°). The functional data were obtained using an echo planar imaging sequence (47 AC-PC slices, 3 mm thick, 3.12 mm by 3.12 mm in plane resolution, 64 × 64 matrix; field of view: 216; TE: 30 ms; TR: 3000 ms; flip angle 90°) lasting 225 s.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging data processing, as well as preprocessing was carried out using FEAT Version 6.0, part of FSL (FMRIB's Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.ul/fsl).

Non-brain tissue was removed from high-resolution anatomical images using Christian Gaser's VBM8 toolbox for SPM843 and fed into feat. Data were motion corrected using MCFLIRT and motion parameters were added as confound variables to the model. In addition, residual outlier timepoints were identified using FSL’s motion outlier detection program and integrated as additional confound variables in the first-level general linear model analysis. Preprocessing further included spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of 8 mm, grand-mean intensity normalization and highpass temporal filtering with sigma=50.0 s.

The two runs (treated as fixed effect) from each participant were combined, except in five participants in whom only one run was available (four ASD, one CON). Subject-level statistical analysis was carried out for the contrast (PAIN>NO PAIN) using FILM with local autocorrelation correction. Registration to high-resolution structural images was carried out using FLIRT. Registration to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space was then further refined using FNIRT (FMRIB's non linear registration tool) nonlinear registration. Group-level analyses were performed using mixed effects general linear model analysis using FLAME 1 with automatic outlier detection. In modeling subject variability, this kind of analysis allows inference about the population from which the subjects are drawn. Z-statistic images were thresholded using clusters determined by Z>2.3 and a (corrected) cluster significance threshold of P=0.05.44 Cluster-corrected images were displayed on a standard brain (fsaverage for the surface and MNI template for the volume).

Between-group differences were assessed using a two-sample unpaired t-test available in FSL.

Correlation analyses

For each group separately, Spearman correlations were computed between whole-brain activation and age, as well as with the subscales of the EQ: emotional EQ, cognitive EQ and social EQ.

In addition, in a post hoc analysis, we examined brain areas that showed significant differences between ASD and CON by defining 3 × 3 × 3 cubes around the peak of activation difference and correlating them with AQ scores. These areas consisted of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) (−40, 34, 20), the left rostrolateral prefrontal cortex (rlPFC) (−34, 46, 4), left temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) (−42, −64, 40) and the left ACC (−14, 24, 24). For each subject, the mean percentage Blood-oxygen-level dependen signal change was extracted for each of those regions of interest for the contrast (PAIN>NO PAIN), using the Featquery tool in FSL, and the Spearman correlations were computed between parameter estimates and AQ scores across all participants, treated as one group.

Results

Behavioral results

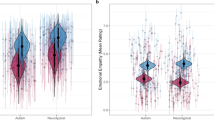

Comparison between ASD and CON showed that individuals with ASD exhibited significantly higher AQ scores (Table 1, Figure 1). For the EQ, total scores as well as the subscores cognitive EQ and social EQ were significantly lower in ASD (P<0.0001). The emotional EQ subscore was also lower in ASD (P=0.01), although it showed more overlap between groups.

During the functional magnetic resonance imaging session, the detection rate of the blue cross was similar in both groups (mean=92.5%, s.d., 11.4 in ASD and mean=88.7%, s.d., 16.5 in CON; not significantly different), indicating that all participants paid attention to the stimuli.

Neuroimaging results

Correlation with age

Age did not a have statistically significant effect on either group on whole-brain activation for the (PAIN>NO PAIN) condition. Statistical comparisons within and between groups were carried out without the addition of age as covariate.

Within-group whole-brain analyses

During the perception of faces expressing pain, both ASD and CON groups exhibited activation in regions involved in face and body processing (inferior occipital gyrus, fusiform face area, extrastriate body areas), in pain processing (fronto-insular cortex, S2, periaqueductal gray), in emotional processing (orbito-frontal cortex, amygdala), as well as in emotional attribution (inferior frontal gyrus, TPJ, superior temporal sulcus (STS)) (Table 2, Figure 2). In addition, the ASD group showed activation in the premotor cortex and the dlPFC, whereas the CON group showed activation bilaterally in the mPFC, as well as in the right anterior cingulate, the anterior temporal cortex and the temporal pole.

Activation for the (PAIN>NO PAIN) condition in participants with ASD (ASD; top panel), control participants (CON) (middle panel) and difference between groups (bottom panel). Separate group data are shown at a threshold of P<0.05, cluster corrected. Between-groups comparison is shown with a threshold of P<0.01.

Between-group whole-brain analysis

At a corrected cluster threshold of P<0.05, no significant differences were present between groups during the perception of faces expressing pain (Table 3,Figure 2). At a more liberal threshold (P<0.01, uncorrected, minimum cluster size of 70), we observed increased activation in the ASD compared with CON in the left dlPFC and rlPFC, the anterior cingulate, the TPJ, and the OFC, as well as in the right VIIIa of the cerebellum. CON had more activation than ASD in the left occipital pole, lateral occipital cortex and the left temporal pole.

Correlations with behavioral measures

Whole-brain analysis

Emotional EQ. Emotional EQ was positively correlated with brain activation in the ASD group (Table 4, Figure 3). Emotional EQ was not correlated with the brain activation in CON. A between-group comparison confirmed significant positive correlations with emotional EQ in ASD compared with CON. Areas showing significant positive correlation with emotional EQ in ASD included bilateral insula, rostral ACC, dorsal ACC, OFC, temporal pole and SMA, as well as the bilateral putamen, caudate and thalamus, the left amygdala and the left hippocampus. In addition, the left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, rlPFC and superior frontal gyrus as well as the right temporal pole were positively correlated with emotional EQ. The vermis as well as the left and right areas VIIIb of the cerebellum also showed positive correlations, as well as the left area IX and VI of the cerebellum.

Cognitive EQ. Cognitive EQ level was not associated with the level of brain activation in either group.

Social EQ. Social EQ was not associated with the level of brain activation in either group.

ROI analysis

In an exploratory analysis, areas that showed increased activation in the ASD versus CON contrast were selected as regions of interest to examine for the presence of a correlation between activation and autistic traits as measured by AQ, when all participants were treated as one single group (Figure 4). These areas consisted of the dlPFC, rlPFC, TPJ and the ACC. All these areas have been associated with stimulus reappraisal. They all showed positive correlations between activation and AQ across the 67 participants, regardless of diagnosis. dlPFC: Spearman's r=0.28, P=0.02; rlPFC: Spearman's r=0.26, P=0.03; TPJ: Spearman's r=0.45; P=0.0001; ACC; Spearman's r=0.25, P=0.04.

Discussion

In contrast to prevailing theories of social functioning in ASD, we observed a lack of significant differences in neural processing between ASD and CON participants during the perception of dynamic facial expression of pain.

In both groups, we observed activation of the pain matrix, in areas consistently associated with empathy-for-pain tasks, and consisting of the thalamus, the midbrain, the OFC, the dACC, the rACC, the SMA and the insula.45 In addition, both groups displayed activation in areas involved in emotional processing (including OFC and amygdala) and in embodiment, including the face and body-processing areas as well as the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), TPJ and STS.

Activation of the mPFC was only observed in CON, although there were no statistical differences between groups at a strict threshold. The mPFC is part of the mentalizing system, underlying mental state attribution and understanding those mental states as different from one’s own.17 The central role of the mPFC in cognitive empathy has also been emphasized in structural and lesion studies.4,46,47 Reduced activation in the mPFC has been described in ASD during mentalizing tasks,48, 49, 50 during introspection51 and has been linked to impairments in self-other distinction.52

Previous studies have reported lack of activation in components of the mirror neurons system during empathy-related processes in ASD, as well as in the mPFC, STS, TP, TPJ and AI (reviewed in Silani et al.53). However, most studies of empathy in ASD have used social stimuli and tasks in which subjects were asked to empathize with an emotional facial expression (for example, sad and happy) and were required to switch between the self- and other-perspective.53,54 Here, we show that seeing another individual’s pain leads both ASD and CON to share the bodily and neural experience, and that perception-action mechanisms6 are operating in both groups. Therefore, our data demonstrate that mirror mechanisms and shared representation system can be spontaneously elicited during perception of pain expression in ASD.

Previous studies exploring explicit empathy for social stimuli (happy, sad and neutral faces) in healthy controls55 have reported age-related activity increase in the fusiform gyrus and in the inferior frontal gyrus, depending on whether the participants were attributing the emotions to self or to other. However, in our study, age did not have a role in the level of brain activation to the perception of the expression of pain in either group for this implicit task.

One of the possible explanations for the lack of differences between ASD and CON is the nature of the emotion that was examined in our study—namely, pain. The vast majority of studies addressing emotion processing in ASD have used ‘social’ emotions, by means of facial expression with emotional and approach/avoidance valences. In the present experiment, CON and ASD participants were observing the facial expression of patients experiencing pain but who were not socially engaging (that is, the patients on the videos were not looking at the camera) and both groups experienced emotional contagion. It has been shown that perceived automatic reactions to pain are more likely to evoke immediate gut-level reactions and emotional engagement leading the observer to hurt in sympathy, whereas the perception of controlled expression involves more cognitive components and ToM abilities.56,57 On the basis of our data, we can posit that different processes are involved in the perception of social stimuli versus evolutionary-older processes such as perceiving distress or pain expressed by another person.5 Being sensitive to other people's suffering has an evolutionary advantage for the care of offspring,58 and perceiving pain and reacting to it with empathy can be considered as an archaic function, as it can be observed in other mammals including rats,59 who have been shown to stop pressing a lever that would provide them food if they see that this action simultaneously provokes an electrical shock to another rat.

Using the current paradigm, participants with ASD and controls did not differ in activation in the STS/superior temporal gyrus and IFG, involved in the perception of dynamic faces and in emotional processing and action representation. The STS has a key role in detecting biological movement and is associated with the mentalizing network.60,61 Our results are in agreement with studies in adults with ASD, showing typical IFG and STS activation when viewing dynamic emotional facial expressions.62,63 The present findings, showing similar activation in areas involved in emotional sharing in participants with ASD and controls, are consistent with the hypothesis that emotional empathy is preserved in ASD. Interestingly, the dissociation between intact affective empathy and impaired cognitive empathy (ToM) in autism is consistent with the theory outlined in ‘zero degrees of empathy’ by Baron-Cohen64 and is the opposite of the profile (impaired affective empathy and intact cognitive empathy) observed in psychopaths (see also Blair65). It is also worth mentioning that no between-group differences were observed in face-processing areas, including the fusiform gyrus, as now reported in several studies using paradigms that require participants’ attention to faces.63,66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75

At a lower threshold, activation in the left TPJ, dACC, dlPFC and rlPFC was increased in ASD compared with controls. These areas are all involved in reappraisal.76 In order to better understand the role of autistic traits in the activation of these areas, we analyzed all participants independently from their diagnosis and examined the relation between AQ score and level of activation in these areas. In each of these areas (left TPJ, dACC, dlPFC and rlPFC), we found a positive correlation between AQ and the level of activation. Recent data from Crystal et al.57 indicate that perceiving pain in others activates both automatic and controlled neuroregulatory processes, and the rlPFC is involved in the evaluation of self-generated information.77 Our findings can be interpreted as the indication of the presence of higher reappraisal /neuroregulatory processes in participants with higher levels of autistic traits, possibly reflecting a strategy to balance the emotional distress induced by the observation of the facial expression of pain. Interestingly, the same set of areas, important for emotion regulation, have been reported in a study examining the brain activation of physicians during patient treatment or during the observation of painful procedures,78, 79, 80 probably reflecting learned coping strategies. As underlined by Cheng et al.,81 future studies will need to further address issues related to emotion regulation in autism.

In typical individuals, emotion understanding and ToM, a capacity that develops around age 2–3 years and relies on the mPFC, follows affective arousal (Figure 5). Emotion understanding allows downregulation of arousal through reappraisal mechanisms involving the dlPFC and the ACC. In ASD, deficits in ToM lead to a potential overwhelming emotional arousal during the perception of pain in others, and increased reappraisal through activation of the dlPFC and the ACC may be the only way to control personal distress. However, others may perceive this increased regulation of emotions as a lack of caring behavior.

Schematic description of reaction to other’s pain in typical individuals (top panel) and in autism spectrum disorder (ASD; bottom panel), modified from Decety.82 In typical individuals, affective arousal (involving subcortical circuits together with the orbito-frontal cortex (OFC) and the superior temporal sulcus (STS)) is followed by emotion understanding, a capacity that develops around the age of 2–3 years, and that overlaps with the theory of mind (ToM)-like processes, involving the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and temporal pole. Emotion understanding leads to the regulation of emotion, through dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), allowing reappraisal mechanisms to downregulate affective arousal. In ASD, increased affective arousal, possibly due to subcortical circuits abnormality, and deficits in ToM processes lead to the need for increased emotional regulation through reappraisal, via increased activation in dlPFC and ACC. This increased regulation of emotions may be perceived by others as a lack of caring behavior.

We further examined the role of the different components of empathy, that is, emotional EQ, assessing emotional contagion, and cognitive and social EQ assessing ToM. Distinct brain networks have been associated with each of these aspects.54,83 Responses to the self-report EQ questionnaires showed statistically significant differences in social and cognitive empathy levels between groups, whereas emotional EQ, while still significantly lower in ASD, showed more overlap between groups (see Figure 1).

As these three aspects of the empathic response seem to be differently affected in ASD, we decided to examine how the different subscales of the EQ questionnaire would be able to predict activation observed in ASD and in CON. We found that the social and cognitive subscales were not correlated with whole-brain activation. However, although many empathy studies have failed to find correlations between empathy subscales and neural activations84 in healthy controls, raising the interesting question of whether those studies had insufficient power to detect those associations or whether there is no association between general empathy scores and neural responses in some context-specific situations,9 our present paradigm—using facial expressions of pain—found a positive correlation between emotional EQ, that examines the affective aspect of empathy, and the level of activation in several areas of the pain matrix, as well as emotional processing and embodiment in ASD, but not in CON. These brain regions included the OFC, ACC, SMA, premotor cortex and insula bilaterally, together with the left IFG, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and temporal pole, as well as amygdala, premotor cortex, SMA, inferior frontal gyrus and caudate. All these areas are involved in emotional contagion. Nummenmaa et al.85 have shown that emotional empathy facilitates somatic, sensory and motor representation of other people’s mental state and increases activation of mirroring areas, supporting a specific role of emotional relative to cognitive empathy. Some of these areas belong to the mirror neurons network, and our data support findings from several groups showing an association between emotional empathy and the activation in the mirror neurons network together with the insula and limbic structures.83,86,87 Interestingly, activation of areas involved in face and body processing was not associated with emotional EQ.

Conclusion

Facial expressions of pain are crucial social cues that alarm others and solicit caring behavior. Empathy for others’ distress is important for adaptive social behavior. To our knowledge, we have conducted the first study using real, dynamic facial expressions of pain to investigate neural correlates of spontaneous empathic processes in normally intelligent individuals with ASD. Our findings show that in ASD, basic automatic processes involved in shared representations of pain are preserved. Our results suggest that rather than a global deficit in empathy and sharing, individuals with ASD show capacity for emotional empathy, but that increased reappraisal, probably to overcome overarousal and personal distress, leads to a failure of appropriate empathic behavior. Further studies directly measuring arousal in similar paradigms will allow a better understanding of empathic processes in ASD.

References

Gonzalez-Liencres C, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Brune M . Towards a neuroscience of empathy: Ootogeny, phylogeny, brain mechanisms, context and psychopathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013; 37: 1537–1548.

Zaki J, Ochsner KN . The cognitive neuroscience of sharing and understanding emotions. In: Decety J (eds). Empathy. The MIT press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012pp 207–226.

Chen Q, Panksepp JB, Lahvis GP . Empathy is moderated by genetic background in mice. PloS ONE 2009; 4: e4387.

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Aharon-Peretz J, Perry D . Two systems for empathy: a double dissociation between emotional and cognitive empathy in inferior frontal gyrus versus ventromedial prefrontal lesions. Brain 2009; 132 ((Pt 3)): 617–627.

Gallese V, Sinigaglia C . What is so special about embodied simulation? Trends Cogn Sci 2011; 15: 512–519.

Preston SD, de Waal FB . Empathy: its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci 2002; 25: 1–20, discussion 20-71.

Merskey H Bogduk N . (1994). Classification of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd edn. International Association for the Study of Pain: Seattle, WA, USA.

Peyron R, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L . Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta-analysis. 2000. Neurophysiol Clin 2000; 30: 263–288.

Decety J . Dissecting the neural mechanisms mediating empathy. Emotion Rev 2011; 3: 92–108.

Singer T, Seymour B, O'Doherty J, Kaube H, Dolan RJ, Frith CD . Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science 2004; 303: 1157–1162.

Morrison I, Lloyd D, di Pellegrino G, Roberts N . Vicarious responses to pain in anterior cingulate cortex: is empathy a multisensory issue? Cogn Affect Behav Neurosc 2004; 4: 270–278.

Botvinick M, Jha AP, Bylsma LM, Fabian SA, Solomon PE, Prkachin KM Viewing facial expressions of pain engages cortical areas involved in the direct experience of pain. NeuroImage 2005; 25: 312–319.

Ochsner KN, Zaki J, Hanelin J, Ludlow DH, Knierim K, Ramachandran T et al Your pain or mine? Common and distinct neural systems supporting the perception of pain in self and other. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2008; 3: 144–160.

Singer T, Seymour B, O'Doherty JP, Stephan KE, Dolan RJ, Frith CD . Empathic neural responses are modulated by the perceived fairness of others. Nature 2006; 439: 466–469.

Saarela MV, Hlushchuk Y, Williams AC, Schurmann M, Kalso E, Hari R . The compassionate brain: humans detect intensity of pain from another's face. Cereb Cortex 2007; 17: 230–237.

Vachon-Presseau E, Roy M, Martel MO, Albouy G, Chen J, Budell L et al Neural processing of sensory and emotional-communicative information associated with the perception of vicarious pain. NeuroImage 2012; 63: 54–62.

Frith CD, Frith U The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron 2006; 50: 531–534.

Budell L, Jackson P, Rainville P . Brain responses to facial expressions of pain: emotional or motor mirroring? NeuroImage 2010; 53: 355–363.

Senju A Spontaneous theory of mind and its absence in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroscientist 2012; 18: 108–113.

Rogers K, Dziobek I, Hassenstab J, Wolf OT, Convit A . Who cares? Revisiting empathy in Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disorders 2007; 37: 709–715.

Dziobek I, Rogers K, Fleck S, Bahnemann M, Heekeren HR, Wolf OT et al Dissociation of cognitive and emotional empathy in adults with Asperger syndrome using the Multifaceted Empathy Test (MET). J Autism Dev Disorders 2008; 38: 464–473.

Jones AP, Happe FG, Gilbert F, Burnett S, Viding E . Feeling, caring, knowing: different types of empathy deficit in boys with psychopathic tendencies and autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010; 51: 1188–1197.

Smith A Cognitive empathy and emotional empathy in human behavior and evolution. Psychol Record 2006; 56: 3–21.

Smith A . The empathy imbalance hypothesis of autism: a theoretical approach to cognitive and emotional empathy in autistic development. Psychol Record 2009; 59: 489–510.

Fan Y-T, Chen C, Chen S-H, Decety J, Cheng Y . Empathic arousal and social understanding in individuals with autism: evidence from fMRI and ERP measurements. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013; e-pub ahead of print.

Singer T . The past, present and future of social neuroscience: a European perspective. NeuroImage 2012; 61: 437–449.

Simon D, Craig KD, Miltner WH, Rainville P . Brain responses to dynamic facial expressions of pain. Pain 2006; 126: 309–318.

Lamm C, Batson CD, Decety J . The neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. J Cogn Neurosci 2007; 19: 42–58.

APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-IV-TR. 2000.

Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A . Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disorders 1994; 24: 659–685.

Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC et al The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disorders 2000; 30: 205–223.

Nygren G, Hagberg B, Billstedt E, Skoglund A, Gillberg C, Johansson M . The Swedish version of the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO-10). Psychometric properties. J Autism Dev Disorders 2009; 39: 730–741.

Wechsler D, Naglieri J . Wechsler Nonverbal Scale of Ability. PsychCorp Edition. Harcourt Assessment: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2006.

Wechsler D . Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI). Harcourt Assessment: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1999.

Baron-Cohen S, Hoekstra RA, Knickmeyer R, Wheelwright S The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ)--adolescent version. J Autism Dev Disorders 2006; 36: 343–350.

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E . The Autism-Spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disorders 2001; 31: 5–17.

Woodbury-Smith MR, Robinson J, Wheelwright S, Baron-Cohen S . Screening adults for Asperger syndrome using the AQ: a preliminary study of its diagnostic validity in clinical practice. J Autism Dev Disorders 2005; 35: 331–335.

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S . The Empathy Quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev Disorders 2004; 34: 163–175.

Muncer S, Ling J . Psychometric analysis of the Empathy Quotient (EQ) scale. Pers Indiv Differ 2006; 40: 1111–1119.

Lawrence EJ, Shaw P, Baker D, Baron-Cohen S, David AS . Measuring empathy: reliability and validity of the Empathy Quotient. Psychol Med 2004; 34: 911–919.

Prkachin KM, Solomon PE . The structure, reliability and validity of pain expression: evidence from patients with shoulder pain. Pain 2008; 139: 267–274.

Ekman P, Friesen WV . Manual for the Facial Action Coding System. Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1978.

Ashburner J, Andersson JL, Friston KJ . Image registration using a symmetric prior--in three dimensions. Hum Brain Mapp 2000; 9: 212–225.

Worsley KJ Statistical analysis of activation images. In: Jezzard P, Matthews PM, Smith SM (eds). Functional MRI: In Introduction to Methods. OUP: Oxford, UK, 2001.

Fan Y, Duncan NW, de Greck M, Northoff G . Is there a core neural network in empathy? An fMRI based quantitative meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011; 35: 903–911.

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Berger BD, Aharon-Peretz J . Characterization of empathy deficits following prefrontal brain damage: the role of the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 2003; 15: 324–337.

Rankin KP, Gorno-Tempini ML, Allison SC, Stanley CM, Glenn S, Weiner MW et al Structural anatomy of empathy in neurodegenerative disease. Brain 2006; 129 ((Pt 11)): 2945–2956.

Castelli F, Frith C, Happe F, Frith U . Autism, Asperger syndrome and brain mechanisms for the attribution of mental states to animated shapes. Brain 2002; 125 ((Pt 8)): 1839–1849.

Spengler S, Bird G, Brass M . Hyperimitation of actions is related to reduced understanding of others' minds in autism spectrum conditions. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68: 1148–1155.

Marsh LE, Hamilton AF . Dissociation of mirroring and mentalising systems in autism. NeuroImage 2011; 56: 1511–1519.

Silani G, Bird G, Brindley R, Singer T, Frith C, Frith U . Levels of emotional awareness and autism: an fMRI study. Soc Neurosci 2008; 3: 97–112.

Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, Bullmore ET, Sadek SA, Pasco G, Wheelwright SJ et al Atypical neural self-representation in autism. Brain 2010; 133 ((Pt 2)): 611–624.

Schulte-Ruther M, Greimel E, Piefke M, Kamp-Becker I, Remschmidt H, Fink GR et al Age dependent changes in the neural substrates of empathy in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013; e-pub ahead of print.

Schulte-Ruther M, Greimel E, Markowitsch HJ, Kamp-Becker I, Remschmidt H, Fink GR et al Dysfunctions in brain networks supporting empathy: an fMRI study in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Soc Neurosci 2011; 6: 1–21.

Greimel E, Schulte-Ruther M, Fink GR, Piefke M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Konrad K . Development of neural correlates of empathy from childhood to early adulthood: an fMRI study in boys and adult men. J Neural Transm 2010; 117: 781–791.

Craig KD, Versloot J, Goubert L, Vervoort T, Crombez G Perceiving pain in others: automatic and controlled mechanisms. J Pain 2010; 11: 101–108.

McCrystal KN, Craig KD, Versloot J, Fashler SR, Jones DN . Perceiving pain in others: validation of a dual processing model. Pain 2011; 152: 1083–1089.

Haidt J, Graham J . When morality opposes justice: conservative have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Soc Justice Res 2007; 20: 97–111.

Church RM . Emotional reactions of rats to the pain of others. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1959; 52: 132–134.

Allison T, Puce A, McCarthy G . Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends Cogn Sci 2000; 4: 267–278.

Frith U . Mind blindness and the brain in autism. Neuron 2001; 32: 969–979.

Bastiaansen JA, Thioux M, Nanetti L, van der Gaag C, Ketelaars C, Minderaa R et al Age-related increase in inferior frontal gyrus activity and social functioning in autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2011; 69: 832–838.

Wicker B, Fonlupt P, Hubert B, Tardif C, Gepner B, Deruelle C . Abnormal cerebral effective connectivity during explicit emotional processing in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2008; 3: 135–143.

Baron-Cohen S . Zero Degrees of Empathy. Penguin: London, England, 2011.

Blair RJ . Fine cuts of empathy and the amygdala: dissociable deficits in psychopathy and autism. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove) 2008; 61: 157–170.

Hadjikhani N, Joseph RM, Snyder J, Chabris CF, Clark J, Steele S et al Activation of the fusiform gyrus when individuals with autism spectrum disorder view faces. NeuroImage 2004; 22: 1141–1150.

Hadjikhani N, Joseph RM, Snyder J, Tager-Flusberg H . Abnormal activation of the social brain during face perception in autism. Hum Brain Mapp 2007; 28: 441–449.

Pierce K, Haist F, Sedaghat F, Courchesne E . The brain response to personally familiar faces in autism: findings of fusiform activity and beyond. Brain 2004; 127: 2703–2716.

Zurcher NR, Donnelly N, Rogier O, Russo B, Hippolyte L, Hadwin J et al It's all in the eyes: subcortical and cortical activation during grotesqueness perception in autism. PloS ONE 2013; 8: e54313.

Bird G, Catmur C, Silani G, Frith C, Frith U . Attention does not modulate neural responses to social stimuli in autism spectrum disorders. NeuroImage 2006; 31: 1614–1624.

Dapretto M, Davies MS, Pfeifer JH, Scott AA, Sigman M, Bookheimer SY et al Understanding emotions in others: mirror neuron dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9: 28–30.

Pierce K, Redcay E . Fusiform function in children with an autism spectrum disorder is a matter of ‘who’. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64: 552–560.

Kleinhans NM, Richards T, Sterling L, Stegbauer KC, Mahurin R, Johnson LC et al Abnormal functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders during face processing. Brain 2008; 131: 1000–1012.

Kleinhans NM, Richards T, Weaver K, Johnson LC, Greenson J, Dawson G et al Association between amygdala response to emotional faces and social anxiety in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia 2010; 48: 3665–3670.

Perlman SB, Hudac CM, Pegors T, Minshew NJ, Pelphrey KA . Experimental manipulation of face-evoked activity in the fusiform gyrus of individuals with autism. Soc Neurosci 2011; 6: 22–30.

McRae K, Gross JJ, Weber J, Robertson ER, Sokol-Hessner P, Ray RD et al The development of emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal in children, adolescents and young adults. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2012; 7: 11–22.

Christoff K, Ream JM, Geddes LP, Gabrieli JD . Evaluating self-generated information: anterior prefrontal contributions to human cognition. Behav Neurosci 2003; 117: 1161–1168.

Jensen KB, Petrovic P, Kerr CE, Kirsch I, Raicek J, Cheetham A et al Sharing pain and relief: neural correlates of physicians during treatment of patients. Mol Psychiatry 2013; e-pub ahead of print.

Cheng Y, Lin CP, Liu HL, Hsu YY, Lim KE, Hung D et al Expertise modulates the perception of pain in others. Curr Biol 2007; 17: 1708–1713.

Decety J, Yang CY, Cheng Y . Physicians down-regulate their pain empathy response: an event-related brain potential study. NeuroImage 2010; 50: 1676–1682.

Mazefsky CA, Pelphrey KA, Dahl RE . The need for a broader approach to emotion regulation research in autism. Child Dev Perspect 2012; 6: 92–97.

Decety J . The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Dev Neurosci 2010; 32: 257–267.

Schulte-Ruther M, Markowitsch HJ, Fink GR, Piefke M . Mirror neuron and theory of mind mechanisms involved in face-to-face interactions: a functional magnetic resonance imaging approach to empathy. J Cogn Neurosci 2007; 19: 1354–1372.

Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T . Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. NeuroImage 2011; 54: 2492–2502.

Nummenmaa L, Hirvonen J, Parkkola R, Hietanen JK . Is emotional contagion special? An fMRI study on neural systems for affective and cognitive empathy. NeuroImage 2008; 43: 571–580.

Bastiaansen JA, Thioux M, Keysers C . Evidence for mirror systems in emotions. Phil Trans R Soc Lond Biol Sci 2009; 364: 2391–2404.

Carr L, Iacoboni M, Dubeau MC, Mazziotta JC, Lenzi GL . Neural mechanisms of empathy in humans: a relay from neural systems for imitation to limbic areas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 5497–5502.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants and their families. We also thank K. Métrailler for her support in participants’ recruitment, C. Burget for her administrative assistance, A. Lissot and J. Snyder for their help in data analysis and technical support, and K.B. Jensen for her insightful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PP00P3–130191 to NH), the Velux Stiftung, the Centre d’Imagerie BioMédicale (CIBM) of the University of Lausanne (UNIL), the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), the Swedish Science Council, as well as the Foundation Rossi Di Montalera. Preparation of the facial pain videos was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hadjikhani, N., Zürcher, N., Rogier, O. et al. Emotional contagion for pain is intact in autism spectrum disorders. Transl Psychiatry 4, e343 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2013.113

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2013.113

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cognitive and Affective Empathy in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-analysis

Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2023)

-

Eye Gaze in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review of Neural Evidence for the Eye Avoidance Hypothesis

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2023)

-

Alexithymia and Autistic Traits as Contributing Factors to Empathy Difficulties in Preadolescent Children

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2022)

-

Alexithymic But Not Autistic Traits Impair Prosocial Behavior

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2022)

-

Prognostic factors and predictors of outcome in children with autism spectrum disorder: the role of the paediatrician

Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2021)