Abstract

The structure evolution and crystallization processes of Sb2Te-TiO2 films have been investigated. The Sb2Te-rich nanocrystals, surrounded by TiO2 amorphous phases, are observed in the annealed Sb2Te-TiO2 composite films. The segregated domains exhibit obvious chalcogenide/TiOx interfaces, which elevate crystallization temperature, impede the grain growth and increase crystalline resistance. Compared with that in conventional Ge2Sb2Te5 film, the shorter time for onset crystallization (25 ns) and amorphization (100 ns) has been achieved in as-deposited (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 film under 60 mW laser irradiation. The corresponding recrystallization and re-amorphization can also be realized in the film. From Johnson-Mehl-Avrami (JMA) analysis, it is further found that the one-dimensional grain growth with controlled interface is dominant for the film during the fast phase-change process. Therefore, (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 film with improved crystallization mechanism is promising for high-stable and fast-speed memory applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phase-change materials are used extensively in optical or nonvolatile electrical data storage because of their large optical or electrical contrast between crystalline and amorphous phases1. Phase-change thin films can be used as the recording and nonlinear mask layers in optical storage2. In rewritable phase-change optical disks, the amorphous marks are produced after irradiation by a recording laser pulse. Then, information marks are read out through the apparent optical reflectivity difference between the amorphous marks and crystalline background3,4. The recorded marks can be erased by heating the media to its crystallization temperature which should be below its melting point5,6. Phase-change films can also serve as a mask layer for super-resolution optical information devices owing to their nonlinear saturable absorption characteristics, which effectively reduce the optical spot size to below diffraction limit7. For non-volatile electrical storage, when high voltage is applied as RESET pulse, the information is erased and the mark becomes amorphous. And the bit is written when SET pulse is applied8,9.

Conventional Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST) that has been widely used in commercial DVD-RAM10 attracts great attentions on the phase-change memory (PCM) applications11,12. However, its properties including poor thermal stability, slow conversion speed, and high power consumption are limited for further applications. Some novel phase-change materials by constructing amorphous-crystalline nano-composite with a small amount of single element, such as Zn13, Mg14 or dielectric material HfO215 are developed for improving thermal stability and reducing power consumption. Compared with the nucleation-dominated GST alloys, binary growth-dominated Sb-Te alloys exhibit faster crystallization speed but their low crystallization temperature and uncontrollable large grain growth limit the practical applications16. In fact, Sb-Te alloys are usually doped with single element V17, Zn18, and C19 et al. for the improvement in amorphous phase stability and crystalline resistance. Besides, previous studies reported that the addition of dielectric material SiO220 or ZnO21 into Sb2Te3 could effectively increase crystallization temperature and crystalline resistance, thus enhancing the thermal stability and reducing the power consumption.

Obviously, nano-composite phase-change material is a new kind of functional storage materials. Its small size effect and dielectric material package function can refine grain growth and increase crystalline resistance so as to reduce the power consumption of the device. Therefore, it is widely used as phase-change layer in PCM for the replacement of conventional single-structure phase-change materials. Nevertheless, some issues still exist in the nano-composite phase-change materials, including (1) The distribution of nanocrystals, crystal size and specific phase precipitation need to be controlled, (2) The interface microstructure stability and crystallization mechanism need to be investigated and clarified for future development.

In this work, the crystallization and microstructure stability of Sb2Te-TiO2 nanocomposite layer are studied for the potential memory applications. TiOx is more stable in thermodynamic and less resistive in electric than SiOx22, which can lower the threshold voltage and power consumption in a memory device based on GST-TiOx phase-change layer22. As a favored doping element, it is surprising that there are few reports of doping TiO2 into Sb2Te for memory applications, and the phase-change kinetics in terms of the fundamental nucleation and growth theories are ambiguous. Therefore, the present work aims at investigating how TiO2 doping can affect the phase-change behavior and determine phase-change kinetics of the Sb2Te-TiO2 films during crystallization process. The results confirm that the TiO2 embedment is able to stabilize the amorphous state. Moreover, an optimized composition of (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 with one-dimensional growth is determined. A reversible fast phase transformation of as-deposited and melt-quenched (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 films upon nanosecond pulsed laser irradiation is demonstrated and the film interface microstructure stability during phase-change process is real-time monitored. All these are of crucial importance for the performance improvement in phase-change materials.

Results and Discussion

Figure 1(a) shows the temperature dependence of the sheet resistance (R-T) upon annealing as-deposited Sb2Te-TiO2 thin films from ambient temperature to 300 °C with a heating rate of 40 °C min−1. According to the R-T behavior, the crystallization temperature (Tc) is determined to be ~156, ~167, ~176, and ~188 °C for the Sb2Te films with TiO2 content of 1.6, 3.3, 5.3, and 9.2 at%, respectively. These values are significantly higher than that of undoped Sb2Te (~144 °C) film. TiO2, as the form of chalcogenide/TiOx interfaces, is introduced to Sb2Te film, which can inhibit surface atomic motion on nanocrystals23 to strengthen the Sb2Te-TiO2 structure. This accounts for the enhanced Tc of the Sb2Te-TiO2 films. Moreover, the crystalline resistance (Rc) is also increased, while amorphous/crystalline resistance ratio remains about 104. The reason is that dispersed TiO2 impede the growth and coalescence of Sb2Te during recrystallization to form structure discontinuities in Sb2Te. The numerous interfacial defects result in the resistance enhancement, indicating that the superheat effect causes the increase in Tc and finally stabilizes the amorphous Sb2Te films.

The data retention is one of the important factors for nonvolatile memories. The maximum temperature for 10-years’ data retention can be extrapolated by fitting the data with the Arrhenius equation: t = τ exp(Ea/kBT)24, where τ, kB, Ea are the proportional time constant, Boltzmann’s constant and crystalline activation energy, respectively. The failure time (t) is defined as the time when the sheet resistance reaches half of its initial magnitude at a specific isothermal temperature (T). As shown in Fig. 1(b), the data retention temperatures for 10 years (T10-year) of the amorphous (Sb2Te)98.4(TiO2)1.6, (Sb2Te)96.7(TiO2)3.3, (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3, and (Sb2Te)90.8(TiO2)9.2 films are 107 °C, 117 °C, 123 °C and 138 °C with the Ea of 3.66 eV, 4.57 eV, 4.78 eV and 6.49 eV, respectively. Compared with the conventional GST (88.9 °C, 2.98 eV)25, the Ea and T10-year values of TiO2-doped Sb2Te films are larger. Higher Ea implies higher energy barrier for crystallization. This is directly associated with improved thermal stability of the amorphous films and prolonged data retention time of memory devices.

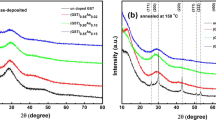

The XRD was carried out in order to clarify the change in structure. Figure 2(a) shows the XRD patterns of as-deposited Sb2Te and Sb2Te-TiO2 films. No crystallization diffraction peak is observed, indicating that all of the as-deposited films are amorphous. The XRD patterns of Sb2Te and Sb2Te-TiO2 films annealed at 250 °C for 3 min are shown in Fig. 2(b–f). A set of diffraction patterns corresponding to crystalline phase of Sb2Te with a hexagonal lattice (p-3 ml) appears in Sb2Te films as shown in Fig. 2(b). For the films with 1.6 at% TiO2 annealed at 250 °C as shown in Fig. 2(c), a change in the preferred orientation of the crystalline Sb2Te phase is found that the peak-(103) becomes intense and sharp similar to peak-(005). Such strong peak-(103) becomes dominated as the TiO2 content increases to 3.3 at% as shown in Fig. 2(d). Further increase of TiO2 content in the Sb2Te films can result in a decrease in the intensity of the crystalline peaks as shown in Fig. 2(e), indicating that TiO2-doping can suppress the crystalline grain growth. Especially, when TiO2 content increases up to 9.2 at% as shown in Fig. 2(f), the peaks (004), (005) and (114) disappear in the (Sb2Te)91.8(TiO2)9.2 film. No other phase can be found in all the films annealed at 250 °C. The grain size is calculated based on the full-width at half maximum (FWHM) of (103) preferred orientation using the Scherrer’s equation. It is found that the grain size decreases from ~30 to ~15 nm with increasing TiO2 content.

TEM analysis was performed to examine the microstructural evolution of Sb2Te-TiO2 films. According to our previous TEM study on pure Sb2Te film19, when the Sb2Te film was annealed at 200 °C, the crystalline Sb2Te phase was precipitated with a large average grain size of 20~30 nm. Figure 3(a) shows the bright-field TEM image of Sb2Te-TiO2 film annealed at 250 °C. The film is crystallized with a small grain size of 10~20 nm. The dark-field TEM image as shown in Fig. 3(b) reveals that the annealed film contains a uniform morphology with embedded dark and bright areas of amorphous contents and crystalline phases. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images as shown in Fig. 3(c,d) makes it possible to measure the interplanar distances and further confirms that the crystal phase is Sb2Te. Meanwhile, the (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 film contains a certain amount of amorphous contents enriched in TiOx phases around Sb2Te crystals, which can interrupt the lattice periodicity, randomize the spatial orientation of Sb2Te grains and form Sb2Te/TiOx interfaces26. This can account for the increase in Tc and Ea in the Sb2Te-TiO2 films. Besides, it also limits sample dimension on the progress of grain growth, and thus affect the crystallization speed27.

The crystallization speed was measured with a static tester under pulsed laser irradiation. The optical contrast ∆R of a material is one of the most important optical parameters in phase-change storage28, which is defined as ∆R = (Rc − Ra)/Ra29, where Rc and Ra are the reflectivity of the crystalline and amorphous states, respectively. For the conventional GST, we find that the film exhibits no obvious change in optical contrast after laser irradiation at 5 mW as shown in Fig. 4(a). Under a laser irradiation power of 20 mW, a slight increase in optical contrast is observed as shown in Fig. 4(b) due to the onset crystallization including grain nucleation, forming stable nuclei and subsequent growth until 158 ns. Then a continuous crystallization leads to a gradual increase in optical contrast in the as-irradiated film. With an increasing laser power of 40 mW, the threshold time for crystallization reduces to 137 ns as shown in Fig. 4(c), where the optical contrast gradually increases until 400 ns. Moreover, it is found that the threshold time for crystallization is only 70 ns and a full crystallization can be achieved at 332 ns during the amorphous-to-crystalline (a → c) phase-change process with a laser irradiation power of 60 mW as shown in Fig. 4(d). Subsequently, as the pulse width increases up to 400 ns, the film exhibits an obvious decrease in optical contrast, corresponding to the reverse phase-change process from crystalline to amorphous phases (c → a).

In comparison, the optical contrast changes for the as-deposited amorphous (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 films irradiated by different laser powers and durations are shown in Fig. 5. When the laser power is 5 mW, there is also no change in the optical contrast as shown in Fig. 5(a) as the pulse width increases from 0 to 250 ns. When the laser power is 20 mW and 40 mW [Fig. 5(b) and (c), respectively], the threshold time for crystallization is determined to be 105 ns and 30 ns, respectively. When the laser power increases to 60 mW, the threshold time for crystallization is around 25 ns and then persist about 100 ns for a complete crystallization as shown in Fig. 5(d). Further irradiation can induce a transition from crystalline to amorphous state. It is due to that the increasing mobility of Sb and Te atoms can be achieved in the film by laser irradiation, and thus the whole system tends to go to an energetically favorable crystalline state30. Furthermore, the Sb and Te atoms in the crystalline state migrate from the lattice sites above melting temperature, and these migrated atoms are quenched during the very short laser irradiation process, leading to a partial amorphization of the film. Figure 5(d) demonstrates that both crystallization and amorphization process can be realized in (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO25.3 film at a laser power of 60 mW. Meanwhile, a faster crystallization and amorphization speed can be achieved in the (Sb2Te)94.7(TiOx)5.3 films compared with those in the conventional GST.

The John-Mehl-Avrami (JMA) theory31 was adopted and JMA plot at laser power of 40 mW was calculated by the JMA model: χ(t) = 1-exp[-(kt)n], where χ(t), n and k is the crystalized fraction of a film, the Avrami coefficient and the effective rate constant, respectively32. In this plot, n is the slope of ln(t) versus ln[-ln(1-χ(t))] plot. Although the JMA plot characterizes the isothermal crystallization on the minute time scale, it is also possible to subtract the n from the nanosecond time scale according to previous reports33,34. As shown in Fig. 6(a), the GST film exhibits an n value of 4.4 in a time scale range from 137 to 302 ns. Up to 137 ns, it is required to generate crystalline nuclei (incubation time). This is in agreement with an n value of 4.8 ± 0.6 in the GST films reported in the previous work35, in which grain growth increases with increasing number of nucleation sites. The Avrami coefficient, n, can be separated into two parts, n = a + bc, where a is the nucleation index; b is the dimensionality of the growth such as 1, 2, or 3 for one-, two-, or three-dimensional growth, respectively; and c is the growth index such as 1 or 0.5 for interface or diffusion controlled growth, respectively. After the incubation process as shown in Fig. 6(a), three dimensional growth of the crystalline phase in both the lateral and vertical directions occurs in the laser-irradiated area until the n value reaches 0.3 ns32. For GST, the b value can be set to 3 (three-dimensional growth) and c is equal to 1. Then, a is taken to be 1.4, which indicates the number of nuclei per unit volume (N) depending on time as follows, N∝ta 35. When pulse width reaches 302 ns, the three-dimensional growth finishes and the n value decreases to 0.34, because crystallization is saturated and limited only to the laser-irradiated area.

The incubation time of the (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 is less than 30 ns, which is significantly faster than that of the GST film. It demonstrates that an incubation period is relatively shorter for crystallization. The n value of 1.36 before saturation implies that the crystal growth mechanism is completely different from that of the GST film. From the viewpoint of the crystal growth, the previous equation is also applied to the (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 films. The nucleation index a and dimensionality b can be obtained as almost 0.36 and 1, respectively, because the growth is interface controlled growth (c = 1). These values directly indicate the one-dimensional crystalline growth for (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 film. As discussed above, the dispersed TiO2 provides additional sites and thus promotes heterogeneous crystal growth in (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 films. The chalcogenide/TiOx interfaces can accelerate the crystal growth and no more nuclei are generated during the crystal growth (a~0). Therefore, the phase-change speed is extraordinarily fast because the (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 films require an extremely short incubation period, which is in good agreement with the results in Fig. 5.

To confirm the microstructure stability between the first and second crystallization effect, the phase-change properties of melt-quenched amorphous films were also measured as shown in Fig. 7. When the laser power is 5 mW [Fig. 7(a)], there is no crystallization as the pulse duration increases from 0 to 250 ns, which is similar to the result in Fig. 5(a). As the laser power increases, the onset recrystallization time of the melt-quenched amorphous film is measured to be 72 ns at 20 mW [Fig. 7(b)], 26 ns at 40 mW [Fig. 7(c)], and 15 ns at 60 mW [Fig. 7(d)], respectively. Moreover, the film scanned by the pulsed laser at a power of 60 mW exhibits a complete crystallization at 88 ns. It is found that the melt-quenched spots are produced in this crystalline area as the longer pulse durations are applied, confirming that re-amorphization of the films can happen and the microstructure stability during a second phase transformation process can be controlled. In addition, the melt-quenched amorphous (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 films exhibit much shorter crystallization and amorphization times at the same laser power compared with the as-deposited amorphous films. This is in accordance with the fact that, the melt-quenched film is more ordered than the as-deposited film36,37. Therefore, it is believed that the controllable crystal growth, fast crystallization, and reversible cycling stability can be demonstrated in the Sb2Te-TiO2 films with one-dimensional growth mode.

Conclusions

In summary, nano-composite TiO2-Sb2Te films have been investigated in terms of phase transition kinetics and microstructures. The increase in crystallization temperature and activation energy of nanocomposite is ascribed to Sb2Te grain refinement and hindrance to grain growth resulted from dispersed TiO2 and the emergence of chalcogenide/TiOx interfaces. Compared with conventional GST, the as-deposited (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 film exhibits a faster crystallization (30 ns) and a shorter onset amorphization (100 ns) under 60 mW. Furthermore, we experimentally confirm the microstructure stability in a second reversible phase transformation process of crystallization and amorphization. JMA theory reveals that the phase transition is prone to be heterogeneous and one-dimensional growth in the crystallization is confirmed for the (Sb2Te)94.7(TiO2)5.3 film.

Methods

Sample preparation

Nano-composite Sb2Te-TiO2 films of ~200 nm thickness were deposited on quartz and SiO2/Si (100) substrates by a magnetron co-sputtering method using individual TiO2 and Sb2Te targets. The chamber was evacuated to 2.2 × 10−4 Pa before Ar gas was introduced to a pressure of 2.5 × 10−1 Pa for the film deposition. The direct current power (Pdc) was fixed at 15 W and applied to a TiO2 target of 50 mm diameter. The amount of TiO2 in the Sb2Te films was adjusted by varying the radio frequency power (Prf) applied to the Sb2Te target of 50 mm diameter. The Prf was fixed at 90, 80, 60, and 30 W in order to vary the TiO2-doping concentration. Pure Sb2Te and GST films with the same thickness were also prepared for comparison.

Characterizations

The stoichiometry of the as-deposited films was confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. The concentrations of TiO2 in the Sb2Te films were determined to be around 1.6, 3.3, 5.3, and 9.2 atomic % (at%). The sheet resistance of the as-deposited films was measured in situ using a four point probe in a vacuum chamber built in-house, as a function of temperature (non-isothermal) or time (isothermal). The time resolution for the resistance measurements under isothermal annealing is 5 s. The structure of as-deposited and annealed films was examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The diffraction patterns were taken in the 2θ range of 10–60° using Cu Kα radiation with a wavelength of 0.154 nm and performed under Bragg conditions for samples. The acceleration voltage for TEM is 200 kV. A static laser tester (PST-1, Nanostorage Co. Ltd., Korea) with a wavelength of 650 nm and laser spot size of 1 μm was used to characterize the crystallization and amorphization behavior. The laser power and pulses width was set from 5 to 70 mW and from 5 to 250 ns, respectively.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Wang, G. et al. Controllable crystal growth and fast reversible crystallization-to-amorphization in Sb2Te-TiO2 films. Sci. Rep. 7, 46279; doi: 10.1038/srep46279 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Lotnyk, A. et al. Real-space imaging of atomic arrangement and vacancy layers ordering in laser crystallised Ge2Sb2Te5 phase change thin films. Acta Mater. 105, 1–4 (2016).

Raoux, S. Phase change materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 39, 25–48 (2009).

Yamada, N., Ohno, E., Nishiuchi, K., Akahira, N. & Takao, M. Rapid-phase transitions of GeTe-Sb2Te3 pseudobinary amorphous thin films for an optical disk memory. J. Appl. Phys. 69, 2849–2856 (1991).

Rios, C. et al. Intergated all-photonic non-volatile multi-level memory. Nat. Photonics 9, 725–732 (2015).

Cheng, H. Y., Raoux, S. & Chen, Y. C. The impact of film thickness and melt-quenched phase on the phase transition characteristics of Ge2Sb2Te5 . J. Appl. Phys, 107, 074308 (2010).

Siegrist, T. et al. Disorder-induced localization in crystalline phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 202–208 (2011).

Borisenko, K. B. et al. Photo-induced optical activity in phase-change memory materials. Sci. Rep. 5, 8770–8774 (2015).

Zhou, X. L. et al. Ti-Sb-Te alloy: A candidate for fast and long-life phase-change memory. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 7627–7634 (2015).

Simpsom, R. et al. Interfacial phase-change memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 501–505 (2011).

Wuttig, M. & Yamada N. Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage. Nat. Mater. 6, 824–832 (2007).

Raoux, S., Welnic, W. & Ielmini, D. Phase change materials and their application to nonvolatile memories. Chem. Rev. 110, 240–267 (2010).

Meena, J. S., Sze S. M., Chand, U. & Tseng, T. Y. Overview of emerging nonvolatile memory technologies. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 9, 526–558 (2014).

Wang, G. X. et al. Phase change behaviors of Zn-doped Ge2Sb2Te5 films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 051906 (2012).

Fu, J. et al. Crystallization characteristics of Mg-Ge2Sb2Te5 films for phase change memory applications. Appl. Suf. Sci. 264, 269–272 (2013).

Song, S. N., Song, Z. T., Liu, B., Wu, L. C. & Feng, S. L. Performance improvement of phase-change memory cell with Ge2Sb2Te5-HfO2 composite films. Appl. Phys. A 99, 767–770 (2010).

Van Pieterson, L., Lankhorst, M. H. R., Van Schijndel, M., Kuiper, A. E. T. & Roosen, J. H. J. Phase-change recording materials with a growth-dominated crystallization mechanism: a materials overview. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 083520 (2005).

Ji, X. L. et al. Vanadium doped Sb2Te3 material with modified crystallization mechanism for phase-change memory application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 243103 (2015).

Shen, X. et al. Enhanced thermal stability and electrical behavior of Zn-doped Sb2Te films for phase change memory application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 131902 (2013).

Wang, G. X. et al. Improved thermal Stability of C-doped Sb2Te films by increasing degree of disorder for memory application. Thin Solid Films 615, 345–350 (2016).

Zhu, M. et al. Phase change characteristics of SiO2 doped Sb2Te3 materials for phase change memory application. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 14, H404–H407 (2011).

Wang, G. X. et al. Reversibility and stability of ZnO-Sb2Te3 nanocomposite films for phase change memory applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 8488–8496 (2014).

Lee, D. et al. Formation of Ge2Sb2Te5-TiOx nanostructures for phase change random access memory applications. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 13, K8–K11 (2010).

Jiang, Q., Tong, H., Hsu, D., Okuyama, K. & Shi, F. Thermal stability of crystalline thin films. Thin Solid Films 312, 357–361 (1998).

Lankhorst, M. H. K., Can Pieterson, L., Van Schijindel, M., Jacobs, B. A. J. & Rijpers, J. C. N. Prospects of doped Sb-Te phase-change materials for high-speed recording. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 42, 863–868 (2003).

Wang, G. X. et al. Improved phase-change characteristics of Zn-doped amorphous Sb7Te3 films for high-speed and low-power phase change memory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 031914 (2013).

Huang, Y. J., Chung, T. C., Wang, C. H. & Hsieh, T. E. Characterizations of AgInSbTe and its nanocomposite thin films for phase-change memory application. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, P113–P118 (2010).

Wang, W. J. et al. Enabling universal memory by overcoming the contradictory speed and stability nature of phase-change materials. Sci. Rep. 2, 360–365 (2012).

Velea, A., Socol, G., Popescu, M. & Galca, A. C. In-situ characterization of the optical and electronic properties in GeTe and GaSb thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 135712 (2015).

Park, S. J., Jang, M. H., Park, S. J., Cho, M. H. & Ko, D. H. Characteristics of phase transition and separation in a In–Ge–Sb–Te system. Appl. Surf. Sci., 258, 9786–9791 (2012).

Sun, X. X. et al. Nanosecond laser-induced phase transitions in pulsed laser deposition-deposited GeTe films. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 133501 (2014).

Christian, J. W. The Theory of Transformations in Metals and Alloys, Part I, Equilibrium and General Kinetic Theory, 2nd ed., pp.15, 525, Pergamon, Oxford (1975).

Weidenhof, V., Friedrich, I., Ziegler, S. & Wuttig, M. Laser induced crystallization of amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 films. J. Appl. Phys. 89, 3168–3176 (2001).

Hyung Jang, M. et al. The phase change effect of oxygen-incorporation in GeSbTe films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, H471–H476 (2011).

Jang, M. H. et al. Ultrafast phase change and long durability of BN-incorporated GeSbTe. J. Mater. Chem. C 3, 1707–1715 (2015).

Ruitenberg, G., Petford-Long, A. K. & Doole, R. C. Determined of the isothermal nucleation and growth parameters for the crystallization of thin Ge2Sb2Te5 films. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 3116–3123 (2002).

Lee, B. S. et al. Observation of the role of subcritical nuclei in crystallization of a gassy solid. Science 326, 980–984 (2009).

Lee, B. S. et al. Distribution of nanoscale nuclei in the amorphous dome of a phase change random access memory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 071907 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 61604083, 61675107, 61377061), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, China (Grant No. LQ15F040002), the Zhejiang Open Foundation of the Most Important Subjects (Grant No. xkxl1532), and was sponsored by the K. C. Wong Magna Fund at Ningbo University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guoxiang Wang performed the experiments with the help from Chao Li and Hui Wang. Qiuhua Nie coordinated this project. Samples were tested by Daotian Shi and Yegang Lu. Data analysis was carried out by Guoxiang Wang and Xiang Shen. The manuscript was written by Guoxiang Wang with help from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Li, C., Shi, D. et al. Controllable crystal growth and fast reversible crystallization-to-amorphization in Sb2Te-TiO2 films. Sci Rep 7, 46279 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46279

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46279

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.