Abstract

In spite of interesting features as flexibility, organic thin-film transistors have commercially lagged behind due to the low mobilities of organic semiconductors associated with hopping transport. Furthermore, organic transistors usually have much larger channel lengths than their inorganic counterparts since high-resolution structuring is not available in low-cost production schemes. Here, we present an organic permeable-base transistor (OPBT) which, despite extremely simple processing without any high-resolution structuring, achieve a performance beyond what has so far been possible using organic semiconductors. With current densities above 1 kA cm−2 and switching speeds towards 100 MHz, they open the field of organic power electronics. Finding the physical limits and an effective mobility of only 0.06 cm2 V−1 s−1, this OPBT device architecture has much more potential if new materials optimized for its geometry will be developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic semiconductors have a low charge carrier mobility μ in comparison to inorganic semiconductors, reducing transconductance and thus switching speed in transistors. However, they offer great potential for flexible electronics due to simple processing techniques and carbon-based materials1,2,3,4. Nevertheless, for most applications, device speed and driving currents need to be raised significantly, while keeping low-cost processing without high-resolution structuring. While common organic field effect transistors reach very high current densities of a few 10 kA cm−2 in the channel region5, the areal current densities remain comparably low. Optimized transistors with short channel lengths reach current densities of 1 to 20 A cm−2 and a transit frequency normalized to the operation voltage of about 1 to 2 MHz V−1, cf. ref. 6, 7, 8, 9. One prominent exception is realized by Münzenrieder et al. fabricating an inorganic thin-film transistor with a footprint current density of ca. 500 A cm−2 and a transit frequency of 135 MHz at 2 V, still meeting the requirements of plastic electronics, e.g. flexibility10. For comparison, modern silicon based MOSFETs easily achieve more than 1 MA cm−2 and transit frequencies greater than 100 GHz, cf. ref. 11. However, it has been shown that organic semiconductors are capable to sustain enormous current densities in the vertical direction (perpendicular to the substrate) towards kA cm−2 for diodes12,13 and up to MA cm−2 for simple devices with thin single layers14. Here, we show that these vertical operation concepts can also be used to realize transistors with outstanding properties. We demonstrate an organic permeable-base transistor (OPBT) which basically resembles the layer stack of a vertical diode with an embedded base electrode in the middle of the stack to control the current flow perpendicular to the substrate. The base electrode contains nano-holes that make it permeable for charge-carriers and allows for high current densities15,16. We demonstrate here transistors with record high current densities above 1 kA cm−2 at low voltages, accompanied by excellent high-frequency characteristics.

Results

Transistor setup

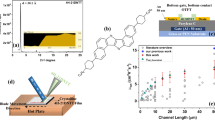

The basic OPBT setup, as shown in Fig. 1a and b, consists of three electrodes emitter, base, and collector embedding two semiconducting layers. The thin aluminum layer in the middle is passivated by a native oxide and controls the charge flow through its nano-size openings by the applied potential17. A detailed description of the operation mechanism can be found in ref. 16. Our results are based on an OPBT configuration as introduced in ref. 18 using C60 as the semiconductor material and an optimized device structuring leading to a state-of-the-art performance as presented in ref. 15. A narrowed top electrode with a width of about 200 μm is used in combination with a structured insulator-window with the same broadness to realize an active area Aact of measured 0.046 mm2 by thermal evaporation and low-resolution shadow masks, compatible with OLED display fabrication technology19.

(a) Device cross-section and electric circuit in common-emitter configuration. Materials: aluminum (Al), chrome (Cr), n-doped C60 (n-C60), intrinsic/undoped C60 (i-C60), native aluminum-oxide (AlOX). Blue arrows indicate the electron flow. (b) Microscope top-view image showing electrode and structuring orientation as well as the active area Aact (yellow). (c) Transfer curves (i-C60: top 30 nm/bottom 100 nm) for different operation voltages VCE. A high on-off ratio of 108, an on-state current density of 75 A cm−2 and subthreshold slope of 85 mV dec.−1 are achieved at a VCE of 2 V. (d) Linear and (e) double logarithmic output characteristic. All curves are limited by a linear law at low voltages and a quadratic law at higher voltages, corresponding to the charge transport through the intrinsic C60 layer which restricts the maximum current of the transfer curve as well.

DC performance

Figure 1c shows the transfer curves of an OPBT for different operation voltages VCE applied between collector and emitter. The OPBT operates even at very low voltages of 1 mV still showing an on-off ratio greater than 102. However, when VCE is higher than 1 V, the current easily reaches a level at which Joule self-heating starts, which is why the source-measuring unit is set to pulse all voltages for currents above 1 mA (>2.2 A cm−2). Effects of self-heating in a similar device geometry have been previously investigated13,20 and will follow for OPBTs, especially as time-resolved pulsed measurements predict that the self-heating is not completely suppressed at higher power input (cf. Supplementary Information). The OPBT has a current density of 75 A cm−2, an on-off ratio of 108, a sub-threshold slope of 85 mV dec.−1 close to the theoretical optimum of 60 mV dec.−1, and a clockwise hysteresis below 75 mV at a moderate VCE of 2 V. Gains greater than 104 are observed (cf. Supplementary Information)21. The output characteristic in Fig. 1d shows a clear saturation behavior, although the channel length of this device is in the nm-range16. Typically, such short channel devices lose their saturation behavior due to short channel effects. We explain this effect by nano-size openings in the base electrode which screens the electric field between emitter and collector to an extent that a partial saturation can take place22,23.

Space-charge limited current

Interestingly, the transfer curves, in Fig. 1c, reach a saturation when the base-emitter voltage VBE gets close to VCE indicated by red squares. Compared to the output characteristic, cf. Fig. 1d and e, these on-state currents correspond to a linear and a quadratic limit at low and a higher VCE, respectively, typically observed for diodes having a space-charge limited current (SCLC)24. This space charge effect in the intrinsic layers is further supported by drift-diffusion simulations in ref. 16, revealing exactly the above mentioned voltage dependence when charge injection can be considered to be ideal. Here, it is a significant advantage of the OPBTs sandwich geometry that a doped charge injection layer can be easily inserted. We use an n-doped C60 layer (n-C60), as visualized in Fig. 1a, to reduce the contact resistance that arises from the interface between the emitter electrode and the upper semiconductor layer25.

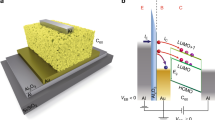

To show that our upper current limit is given by SCLC, the corresponding Mott-Gurney law

is used to describe the L-dependence (ε and ε0 are related to the permittivity)26. We investigate samples of different intrinsic layer thicknesses on top of the base, while the layer underneath the base remains constant so that the growth and the morphology of the base electrode can be considered to be unaffected. Figure 2a presents the output characteristic in double-logarithmic scale, each taken at a VBE of 1.5 V. The currents scale with a cubic thickness dependence as predicted in Eq. 1. However, neither the total thickness of both intrinsic layers nor the thickness of the top intrinsic layer can be used to bring all curves together. Instead, a reduced effective length Leff, lying between the two thicknesses above, has to be used to achieve a good agreement after rescaling. This behavior can easily be understood by considering that in the on-state of the OPBT, charges strongly accumulate in front of the native oxide of the base electrode, leading to a formation of a highly conductive region which can be treated as a ‘virtual contact’16. As sketched in Fig. 2b, the charge transport through the upper and the lower intrinsic layer behaves in each case like a single SCLC element of length L1 and L2, respectively.

(a) Output characteristics at a VBE of 1.5 V for different C60 layer thicknesses are normalized by the third power of the effective device length L eff to prove space-charge limited currents in OPBTs. A bulk mobility perpendicular to the substrate of 0.06 cm2 V−1s−1 is extracted. (b) Visualization of the reduced Leff as the sum of two SCLC devices connected in series.

If these two elements are connected in series, as realized by the virtual contact, one can show that the current-voltage characteristics still follows Eq. 1 (cf. Supplementary Information), but with

as an effective length.

These results can be concluded as follows: Firstly, the result allows to extract the bulk mobility of C60 for the charge transport perpendicular to the substrate of μ = 0.06 cm2 V−1s−1 (ε of C60 is ca. 4)12. Although the value is quite low in comparison to mobilities measured in OFETs, it allows for the excellent performance discussed above and should further motivate material scientists to put more attention on improving bulk mobilities of organic semiconductors27,28. Lateral field-effect mobilities now easily reach values up to 10 cm2 V−1s−1, cf. ref. 29. If it would be possible to apply this achievements to an OPBT, more than 100 times higher current densities (>1 kA cm−2) are possible at a low operation voltage of 1 V and a lower power dissipation. Secondly, as the major limitation is revealed to be SCLC, devices have to be as thin as possible, always chosen as a tradeoff between performance, device stability (electrical shorts), and reasonable breakdown voltages. This basically means that for a given charge carrier mobility and dimension of the semiconductor layer, the OPBT is able to drive the highest possible current densities a semiconductor can realize. All restrictions which can be seen at low voltages in the output characteristics, cf. Fig. 1d, are the restrictions which every transistor, having a vanishing channel resistance, at least has. This means, somewhat counter-intuitively, that the nano-sized openings of base electrode do not limit the charge transport. Thirdly, the voltage dependence predicts a superlinear increase when higher voltages are applied so that extreme current densities above 1 kA cm−2 are in reach.

Towards 1 kA cm−2

To prove this implication, we change our electrode layout in a way that the emitter electrode gets wider in order to reduce its resistance. Samples with narrow emitter electrodes show a linear current-voltage relation at highest current caused by the electrode resistance of about 20 Ω and we observe that the top electrode basically rips off at the edges due to high fields and strong power dissipation (cf. Supplementary Information). When we use a wider emitter electrode, the active area of the OPBT remains constant, but is structured by two insulating layers with free stripes of 200 μm perpendicular to each other17.

As seen in Fig. 3, the samples show similar on-state current densities compared to the results in Fig. 1 at voltages below 2 V. The off-state current densities increase by using this structuring method, probably due to larger direct emitter-collector electrode overlap, but do not influence the characteristics of the on-state. In this way, we can prove that a current density of 1.1 kA cm−2 (501 mA) is driven at a VCE of 7 V by the OPBT and a power above 1 W is applied to the structure for a short time. The non-destructive character of the measurement is proven by a dual sweep of the gate-source voltage in all cases allowing to switch from off to on-state and back, even though a hysteresis is introduced for the utmost curve. Please note that the current density in the nano-size base openings must be even much higher, estimated to be a factor of 100 to 1000 larger.

Transfer curves (i-C60: top 30 nm/bottom 50 nm) of a device with optimized, broad electrode layout at different operation voltages VCE. Applying a VCE of 7 V leads to current densities in excess of 1 kA cm−2 (red line). All measurements are done with dual sweep to confirm nondestructive operation. Inset: Microscope image of the OPBT with the broaden emitter electrode.

While the device cannot permanently operate at such high currents with the present thermal design of the sample, there are still cases where even our non-optimized devices can be used. For example, a transmitter circuit can radiate with an increased power, but only for a short time to decrease the power consumption of a stand-alone device. Further, selection transistors in display circuits have to be very fast, as they have to refresh each pixel at a minimum of time. I.e. high transconductance, high switching speed, and high on-off ratio are necessary, but not steady-state operation.

AC performance

The switching speed of the OPBT is investigated by measuring the transit frequency fT at which unity current gain is reached, cf. Fig. 4a (and Supplementary Information). We use a direct-fT measurement setup and optimized OPBTs regarding high currents15,30. At a current density j of 40 A cm−2 and a VCE of about 3.6 V, the OPBT (top 30 nm/bottom 100 nm) amplifies signals up to 11.8 MHz, although the electrode layout is not yet optimized for reduced parasitic capacitances. Following the fT vs. j characteristic, much higher fT of about 100 MHz are expected if the current would be set to 1 kA cm−2. However, the fT-measurement is limited to current densities the device can withstand at steady-state conditions.

(a) Measured transit frequencies fT at different current densities. An fT up to 11.8 MHz is reached at a current density of 40 A cm−2. The frequency-current dependence predicts an fT in the range of 100 MHz if a current density of 1 kA cm−2 would be applied. (b) AC-coupled performance of an OPBT in a Colpitts oscillator circuit using discrete R-L-C components (cf. Supplementary Information). Large-swing oscillations up to 5.22 MHz are close to an ideal sinus (fit as solid line).

In order to demonstrate the frequency performance in a real circuit, we assemble a modified Colpitts oscillator using discrete passive R-L-C elements with the OPBT as active element (cf. Supplementary Information). As seen in Fig. 4b, the OPBT shows stable oscillations at frequencies of 1.87 MHz, 3.0 MHz, and 5.22 MHz when circuit supply voltages of 4.11 V, 7.10 V, and 7.37 V are applied, respectively. The signal is clearly pronounced with peak-to-peak voltages of 4 V and the output signal has a high-quality sinusoidal waveform. Oscillations of 1.87 MHz at 951 μA and 3.00 MHz at 3.2 mA are very close to the corresponding fT shown in Fig. 4a, i.e. 1.6 MHz and 3.4 MHz, respectively. However, oscillation at 5.22 MHz is only possible at a higher current of 20 mA where the transit frequency is approximately 10 MHz. This limitation might be imposed by a non-negligible resistance of the base electrode, i.e. the internal resistor network behaves like a filter at high frequencies (cf. Supplementary Information).

Conclusion

We present an organic permeable base transistor design which achieves an outstanding performance. The best OPBTs reach an on-off ratio of 108, a subthreshold slope of 85 mV dec.−1 and a current density of 75 A cm−2 at an operation voltage of 2 V. At higher voltages, we achieve footprint current densities above 1 kA cm−2, introducing a new regime of operation to organic transistors. These high current densities point to transit frequencies in the 100 MHz range. The performance can even be further enhanced when the latest achievements for lateral field-effect mobilities can be transferred to vertical bulk mobilities. Thus, in future even much better vertical organic transistors could be realized with our approach.

Methods

Sample preparation

The OPBTs presented are built in a single chamber UHV-tool and on one glass substrate previously cleaned with N-Methylpyrrolidone, distilled water, ethanol, and Ultra Violet Ozone Cleaning System. By using thermal vapor deposition at high vacuum conditions (p < 10−7 mbar), the layer stack (Fig. 1a) is realized by subsequently depositing thin films through laser-cut, stainless steel shadow masks. The deposition system includes a wedge for realizing samples of different layer thickness in one run while other layers remain equal. The layer stack, evaporation rates and treatments of the OPBTs are: Al 100 nm (1 Å s−1)/Cr 10 nm (0.1 Å s−1)/i-C60 wedge 50, 100 nm (1 Å s−1)/Al 15 nm (1 Å s−1)/15 min oxidation at air/i-C60 wedge 30, 50, 100 nm/1 x or 2 x (perpendicular to each other) SiO 200 nm with a free stripe of 0.2 mm (1 Å s−1)/n-C60 20 nm (0.4 Å s−1) co-evaporating C60 with W2 (hpp)4 (purchased from Novaled AG, Dresden) using 1 wt%/Cr 10 nm (0.1 Å s−1)/Al 100 nm (1 Å s−1)/encapsulation in a nitrogen atmosphere using UV cured epoxy glue without UV exposure of the active area/annealing for 2 h at 150 °C in a nitrogen glove-box on a heat plate. The current density of 1 kA/cm2 is reached for a device with a broad top electrode (600 μm) and a C60 bottom thickness of 50 nm and a top thickness of 30 nm. The transit frequency of 11.8 MHz is shown for an OPBT with a narrowed top electrode (200 μm) and a C60 bottom thickness of 100 nm and a top thickness of 30 nm. In all cases, the active area is about (200 × 200) μm2, realized with the support of additional insulating layers.

Device characterization

Electrical DC-characteristics are measured with a parameter analyzer Keithley 4200-SCS, and with a source measure unit (SMU Keithley 2602A) enabling voltage-pulses with a minimum time of 250 μs. Frequency measurements are realized with an optimized measuring setup, similar to ref. 30.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Klinger, M. P. et al. Organic Power Electronics: Transistor Operation in the kA/cm2 Regime. Sci. Rep. 7, 44713; doi: 10.1038/srep44713 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10 April 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Zhou, L. et al. All-organic active matrix flexible display, Appl. Phys. Lett. 88(8), 083502-083502–3 (2006).

Walzer, K., Maennig, B., Pfeiffer, M. & Leo, K. Highly efficient organic devices based on electrically doped transport layers, Chem. Rev. 107(4), 1233–1271 (2007).

Sirringhaus, H. 25th anniversary article: Organic field-effect transistors: The path beyond amorphous silicon, Adv. Mater. 26(9), 1319–1335 (2014).

Kheradmand-Boroujeni, B. et al. Small-signal characteristics of fully-printed high-current flexible all-polymer three-layer-dielectric transistors, Org. Electron. 34, 267–275 (2016).

Sawabe, K. et al. Current-confinement structure and extremely high current density in organic light-emitting transistors, Adv. Mater. 24(46), 6141–6146 (2012).

Klauk, H., Organic thin-film transistors, Chem. Soc. Re 39, 2643–2666 (2010).

Kitamura, M. & Arakawa, Y. High current-gain cutoff frequencies above 10 MHz in n-channel C60 and p-channel pentacene thin-film transistors, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 50(1S2), 01BC01 (2011).

Ante, F. et al. Contact resistance and megahertz operation of aggressively scaled organic transistors, Small 8(1), 73–79 (2012).

Uno, M., Cha, B.-S., Kanaoka, Y. & Takeya, J. High-speed organic transistors with three-dimensional organic channels and organic rectifiers based on them operating above 20 MHz, Org. Electron. 20(0), 119–124 (2015).

Münzenrieder, N. et al. Flexible self-aligned amorphous InGaZnO thin-film transistors with submicrometer channel length and a transit frequency of 135 MHz, IEEE Trans. El. Dev. 60(9), 2815–2820 (2013).

Kao, H. et al. DC-RF performance improvement for strained 0.13 μm MOSFETs mounted on a flexible plastic substrate, IEEE MTTS Int. Microw. Symp. 2043–2046 (2006).

Im, D., Moon, H., Shin, M., Kim, J. & Yoo, S. Towards gigahertz operation: Ultrafast low turn-on organic diodes and rectifiers based on C60 and tungsten oxide, Adv. Mater. 23(5), 644–648 (2011)

Fischer, A. et al. Self-heating effects in organic semiconductor crossbar structures with small active area, Org. Electron. 13(11), 2461–2468 (2012).

Matsushima, T. & Adachi, C. Observation of extremely high current densities on order of MA/cm2 in copper phthalocyanine thin-film devices with submicron active areas, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 46(12L), L1179 (2007).

Klinger, M. P. et al. Advanced organic permeable-base transistor with superior performance, Adv. Mater. 27(47), 7734–7739 (2015).

Kaschura, F. et al. Operation mechanism of high performance organic permeable base transistors with an insulated and perforated base electrode, J. Appl. Phys. 120(9), 094501 (2016).

Fischer, A. A vertical C60 transistor with a permeable base electrode, Ph.D. thesis, TU Dresden. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa-180780 (2015).

Fischer, A., Scholz, R., Leo, K. & Lüssem, B. An all C60 vertical transistor for high frequency and high current density applications, Appl. Phys. Lett. 101(21) (2012).

Hack, M., Weaver, M. S., So, W.-Y. & Brown, J. J. 40.1: Novel two mask AMOLED display architecture, SID Int. Symp. Dig. Tec. 45(1), 567–569 (2014).

Fischer, A. et al. Self-heating, bistability, and thermal switching in organic semiconductors, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110(12), 126601 (2013).

Klinger, M. P., Dollinger, F. et al. Organic permeable base transistors for flexible and electronic circuits, ScienceOpen Posters; 10.14293/P2199-8442.1.SOP-PHYS.PIRZBG.v1. (2016)

Haddock, J. N. et al. A comprehensive study of short channel effects in organic field-effect transistors, Org. Electron. 7(1), 45–54 (2006).

Austin, M. D. & Chou, S. Y. Fabrication of 70 nm channel length polymer organic thin-film transistors using nanoimprint lithography, Appl. Phys. Lett. 81(23), 4431–4433 (2002).

Wetzelaer, G. Charge transport and recombination in organic-semiconductor diodes, Ph.D. thesis, University of Groningen. http://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/9753517/20140328_Thesis.pdf. (2014).

Menke, T., Ray, D., Meiss, J., Leo, K. & Riede, M. In-situ conductivity and seebeck measurements of highly efficient n-dopants in fullerene C60, Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 093304 (2012).

Mott, N. F. & Gurney, R. W. Electronic processes in ionic crystals, 2nd Edition, Clarendon Press (Oxford, 1953).

Zhang, X.-H., Domercq, B. & Kippelen, B. High-performance and electrically stable C60 organic field-effect transistors, Appl. Phys. Lett. 91(9), 092114 (2007).

Schwabegger, G. et al. High mobility, low voltage operating C60 based n-type organic field effect transistors, Synthetic Metals 161(19–20), 2058–2062 (2011).

Bittle, E. G., Basham, J. I., Jackson, T. N., Jurchescu, O. D. & Gundlach, D. J. Mobility overestimation due to gated contacts in organic field-effect transistors, Nat. Comm. 7 (2016).

Kheradmand-Boroujeni, B. et al. Analog characteristics of fully printed flexible organic transistors fabricated with low-cost mass-printing techniques, IEEE Trans. El. Dev. 61(5), 1423–1430 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work is financed by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under Grant Agreement No. FP7-267995 (NUDEV), the German Research Foundation (Grant LE 747/48-1) within the Cluster of Excellence ‘Center for Advancing Electronics Dresden’ (cfaed), the DFG project ‘Flexible Active Radar Backscatter Tag in Organic Electronics’ (FlexART, EL 506/22-1) and in part by the DFG project ‘Low-Voltage High-Frequency Vertical Organic Transistors (HFOE, EL 506/13-1)’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P.K. designed the transistors, performed the DC measurements, and analyzed most of the data. He wrote the manuscript together with A.F. who guided and set the focus of the experiments. B.-K.B. performed the fT measurements and designed the oscillator. F.K. and J.W. were involved in the sample preparation and made essential contributions to the interpretation of the data. F.E. and K.L. motivated and supervised this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Klinger, M., Fischer, A., Kaschura, F. et al. Organic Power Electronics: Transistor Operation in the kA/cm2 Regime. Sci Rep 7, 44713 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44713

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44713

This article is cited by

-

Organic Devices: Fabrication, Applications, and Challenges

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

-

Integrated complementary inverters and ring oscillators based on vertical-channel dual-base organic thin-film transistors

Nature Electronics (2021)

-

Organic circuits reach new heights

Nature Electronics (2021)

-

Efficient and low-voltage vertical organic permeable base light-emitting transistors

Nature Materials (2021)

-

Vertical organic permeable dual-base transistors for logic circuits

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.